Last Days of the MASH 211

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trend Analysis the Israeli Unit 8200 an OSINT-Based Study CSS

CSS CYBER DEFENSE PROJECT Trend Analysis The Israeli Unit 8200 An OSINT-based study Zürich, December 2019 Risk and Resilience Team Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich Trend analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study Author: Sean Cordey © 2019 Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zurich Contact: Center for Security Studies Haldeneggsteig 4 ETH Zurich CH-8092 Zurich Switzerland Tel.: +41-44-632 40 25 [email protected] www.css.ethz.ch Analysis prepared by: Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zurich ETH-CSS project management: Tim Prior, Head of the Risk and Resilience Research Group, Myriam Dunn Cavelty, Deputy Head for Research and Teaching; Andreas Wenger, Director of the CSS Disclaimer: The opinions presented in this study exclusively reflect the authors’ views. Please cite as: Cordey, S. (2019). Trend Analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study. Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich. 1 Trend analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study . Table of Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 Historical Background 5 2.1 Pre-independence intelligence units 5 2.2 Post-independence unit: former capabilities, missions, mandate and techniques 5 2.3 The Yom Kippur War and its consequences 6 3 Operational Background 8 3.1 Unit mandate, activities and capabilities 8 3.2 Attributed and alleged operations 8 3.3 International efforts and cooperation 9 4 Organizational and Cultural Background 10 4.1 Organizational structure 10 Structure and sub-units 10 Infrastructure 11 4.2 Selection and training process 12 Attractiveness and motivation 12 Screening process 12 Selection process 13 Training process 13 Service, reserve and alumni 14 4.3 Internal culture 14 5 Discussion and Analysis 16 5.1 Strengths 16 5.2 Weaknesses 17 6 Conclusion and Recommendations 18 7 Glossary 20 8 Abbreviations 20 9 Bibliography 21 2 Trend analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study selection tests comprise a psychometric test, rigorous Executive Summary interviews, and an education/skills test. -

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the U.S. Military Arena: Social Action in the Name of Diagnosis, Treatment, and Disability Compensation

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the U.S. Military Arena: Social Action in the Name of Diagnosis, Treatment, and Disability Compensation by Michael P. Fisher DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Sociology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO Copyright 2013 by Michael P. Fisher ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is a product of the generosity and support of numerous people. I am grateful for the inspiration, encouragement, and exceptional guidance I received from my committee: Janet K. Shim, Robert Newcomer, Adele E. Clarke, and Stephen Zavestoski. Each has shown me not only what it means to be a scholar but one who brings passion and excellence to everything they do. My committee chair, Janet, provided unwavering support and direction, always encouraging me to follow my intellectual interests. Her thoughtful and constructive feedback continually pushed my work to higher levels. Likewise, Janet’s intense dedication to my learning was evident in every email and phone conversation, even as I conducted my fieldwork 3,000 miles away. I am extremely fortunate to have had the opportunity to learn from such a caring, talented, and imaginative group of scholars. My work has also benefitted from the insights of other scholars I have been privileged to work with throughout my graduate studies. I am deeply appreciative of the support and guidance I received from colleagues at RAND and at the Department of Veterans Affairs. My gratitude also goes to Allan V. Horwitz, who served as a reader of my qualifying exam, and whose scholarship has inspired my own. -

North Korea's Political System*

This article was translated by JIIA from Japanese into English as part of a research project to promote academic studies on the international circumstances in the Asia-Pacific. JIIA takes full responsibility for the translation of this article. To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your personal use and research, please contact JIIA by e-mail ([email protected]) Citation: International Circumstances in the Asia-Pacific Series, Japan Digital Library (March 2016), http://www2.jiia.or.jp/en/digital_library/korean_peninsula.php Series: Korean Peninsula Affairs North Korea’s Political System* Takashi Sakai** Introduction A year has passed since the birth of the Kim Jong-un regime in North Korea following the sudden death of General Secretary Kim Jong-il in December 2011. During the early days of the regime, many observers commented that all would not be smooth sailing for the new regime, citing the lack of power and previ- ous experience of the youthful Kim Jong-un as a primary cause of concern. However, on the surface at least, it now appears that Kim Jong-un is now in full control of his powers as the “Guiding Leader” and that the political situation is calm. The crucial issue is whether the present situation is stable and sustain- able. To consider this issue properly, it is important to understand the following series of questions. What is the current political structure in North Korea? Is the political structure the same as that which existed under the Kim Jong-il regime, or have significant changes occurred? What political dynamics are at play within this structure? Answering these questions with any degree of accuracy is not an easy task. -

IDF Special Forces – Reservists – Conscientious Objectors – Peace Activists – State Protection

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: ISR35545 Country: Israel Date: 23 October 2009 Keywords: Israel – Netanya – Suicide bombings – IDF special forces – Reservists – Conscientious objectors – Peace activists – State protection This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on suicide bombs in 2000 to January 2002 in Netanya. 2. Deleted. 3. Please provide any information on recruitment of individuals to special army units for “chasing terrorists in neighbouring countries”, how often they would be called up, and repercussions for wanting to withdraw? 4. What evidence is there of repercussions from Israeli Jewish fanatics and Arabs or the military towards someone showing some pro-Palestinian sentiment (attending rallies, expressing sentiment, and helping Arabs get jobs)? Is there evidence there would be no state protection in the event of being harmed because of political opinions held? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on suicide bombs in 2000 to January 2002 in Netanya. According to a 2006 journal article published in GeoJournal there were no suicide attacks in Netanya during the period of 1994-2000. No reports of suicide bombings in 2000 in Netanya were found in a search of other available sources. -

The Vietnam War 47

The Vietnam War 47 Chapter Three The Vietnam War POSTWAR DEMOBILIZATION By the end of 1945, the Army and Navy had demobilized about half their strength, and most of the rest was demobilized in 1946. Millions of men went home, got jobs, took advantage of the new Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (commonly known as the “GI Bill,” passed in 1944), got married, and started the “baby boom.” Just as in the period following victory in World War I, few Americans paid much attention to national defense. The newly created Department of Defense (formed in the 1947 merger of the War Department and the Navy Department) faced several concurrent tasks: demobilizing the troops; selling off surplus equipment, land, and buildings; and calculating what defense forces the United States actually needed. The govern- ment adopted a postwar defense policy of containing communism, centered on supporting the governments of foreign countries struggling against internal communists. In its early stages, containment called for foreign aid (both military and economic) and limited numbers of military advisers. The Army drew down to only a few divisions, mostly serving occupation duty in Germany and Japan, and most at two-thirds strength. So few men were volunteering for the military that, in 1948, Congress restored a peacetime draft. The world began looking like a more dangerous place when the Soviets cut off land access to Berlin and backed a coup in Czechoslovakia that replaced a coalition government with a communist one. Such events, in addition to the campaign led by Senator Joe Mc- Carthy to expose any possible American communists, stoked fears of a world- wide communist movement. -

International Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION Vol

International Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION Vol. XXIII No 1 2017 RISK MANAGEMENT IN THE DECISION MAKING PROCESS CONCERNING THE USE OF OUTSOURCING SERVICES IN THE BULGARIAN ARMED FORCES Nikolay NICHEV “Vasil Levski“ National Military University, Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria [email protected] Abstract: Outsourcing services in the armed forces are a promising tool for reducing defence spending which use shall be determined by previously made accurate analysis of peacetime and wartime tasks of army structures. The decision to implement such services allows formations of Bulgarian Army to focus on the implementation of specific tasks related to their combat training. Outsourcing is a successful practice which is applied both in the armies of the member states of NATO and in the Bulgarian Army. Using specialized companies to provide certain services in formations provides a reduction in defence spending, access to technology and skills in terms of financial shortage. The aim of this paper is to analyse main outsourcing risks that affect the relationship between the military formation of the Bulgarian army, the structures of the Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Bulgaria and service providers, and to assess those risks. The basic steps for risk management in outsourcing activities are determined on this base. Keywords: outsourcing, risk management, outsourcing risk 1. Introduction It is measured by its impact and the Outsourcing is an effective tool to generate probability of occurrence, and its new revenue, and the risks that may arise, management is the process of identifying, draw our attention to identifying the main analysing, evaluating, monitoring, types of outsourcing risks. This requires the countering and reporting the risks that may focus of current research on studying and affect the achievement of the objectives of evaluating the possibility of the occurrence an organisation and the implementation of of such risks, and the development of a the necessary control activities in order to system for risks management on this basis. -

Unit 6 Light EXPLORE

EXPLORE Unit Six: Unit Six: Light Table of Contents Light Interdisciplinary Unit of Study I. Unit Snapshot ............................................................................................ 2 II. Introduction ............................................................................................... 4 NYC DOE III. Unit Framework ......................................................................................... 6 IV. Ideas for Learning Centers ......................................................................... 10 V. Foundational and Supporting Texts ...........................................................24 VI. Inquiry and Critical Thinking Questions for Foundational Texts ................. 26 VII. Sample Weekly Plan................................................................................. 29 VIII. Student Work Samples .............................................................................. 35 IX. Supporting Resources ............................................................................... 37 X. Foundational Learning Experiences: Lesson Plans ..................................... 38 XI. Appendices ...............................................................................................54 The enclosed curriculum units may be used for educational, non- profit purposes only. If you are not a Pre-K for All provider, send an email to [email protected] to request permission to use this curriculum or any portion thereof. Please indicate the name and location of your school -

Countering Terrorism Online with Artificial Intelligence an Overview for Law Enforcement and Counter-Terrorism Agencies in South Asia and South-East Asia

COUNTERING TERRORISM ONLINE WITH ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AN OVERVIEW FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT AND COUNTER-TERRORISM AGENCIES IN SOUTH ASIA AND SOUTH-EAST ASIA COUNTERING TERRORISM ONLINE WITH ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE An Overview for Law Enforcement and Counter-Terrorism Agencies in South Asia and South-East Asia A Joint Report by UNICRI and UNCCT 3 Disclaimer The opinions, findings, conclusions and recommendations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Unit- ed Nations, the Government of Japan or any other national, regional or global entities involved. Moreover, reference to any specific tool or application in this report should not be considered an endorsement by UNOCT-UNCCT, UNICRI or by the United Nations itself. The designation employed and material presented in this publication does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoev- er on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Contents of this publication may be quoted or reproduced, provided that the source of information is acknowledged. The au- thors would like to receive a copy of the document in which this publication is used or quoted. Acknowledgements This report is the product of a joint research initiative on counter-terrorism in the age of artificial intelligence of the Cyber Security and New Technologies Unit of the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Centre (UNCCT) in the United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism (UNOCT) and the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI) through its Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics. -

Pdf 2 7/16/10 6:59:17 AM U.S

111th Congress, 2nd Session House Document 111–131 P R O C E E D I N G S of the 109TH ANNUAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Orlando, Florida August 16-21, 2008 Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed. U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2010 57–405 I 57-405109thProc.pdf 2 7/16/10 6:59:17 AM U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the Ameri- can Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House docu- ments of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] II LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Madam Speaker: In conformance with the provisions of Public Law No. 620, 90th Congress, approved October 22, 1968, I am transmitting to you herewith the proceedings of the 109th National Convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, held in Orlando, Florida, August 16-21, 2008, which is submitted for printing as a House Document. -

Mp-Msg-056-23

Simulation Environment for CAX in Joint Training Lt. Col. Orlin Nikolov General Staff of Bulgarian Army [email protected] Dr. Juliana Karakaneva Defence Advanced Research Institute, Rakovski Defence and Staff College [email protected] Mr. James Hendley MPRI team [email protected] ABSTRACT The Computer Assisted Exercise (CAX), based on the constructive simulation is natural continuation of the staff and forces live training at all levels. Being a contemporary approach for preparation and training, CAX gives a possibility to present the staff training and readiness, to train different courses of action and choose the most appropriate one, to improve the commanders’ management skills and to assemble the staffs and teams. The paper outlines the challenges under transformation of the Bulgarian Armed Forces, a training approach of the military units and the interaction with other ministries and agencies in simulation environment. It reveals the terms of reference for the development and application of the simulation in preparation of the units through providing not only direct training capability, but also an interoperability in multinational environment, as well as a regional stability through conducting CAX with neighbouring NATO and non-NATO countries. 1.0 INTRODUCTION During the last two years a team of the Bulgarian National Center for Modeling and Simulations (NCMS) has been established in National Military Training Complex (Figure 1). Its primary objective is to assist the training of commanders and staffs from battalion and equivalent to Joint Task Force level through the use of the Joint Conflict and Tactical Simulation (JCATS) system and NATO command and staff procedures in order to plan, organize, and conduct any type of operations, strengthen the interoperability with NATO, and to achieve General Staff and Ministry of Defense training and planning requirements. -

January/February 2008

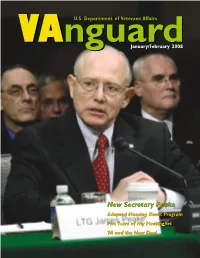

VAnguard outlook January/February 2008 New Secretary Peake Adapted Housing Grant Program Five Years of My HealtheVet VA and the New Deal January/February 2008 1 VAnguard Features FY 2009 Budget Proposal: $93.7 Billion 6 Seamless transition, compensation and pension initiatives top priorities Honoring Distinguished Service in the Pacific 7 Coast Guard commandant visits Punchbowl to dedicate memorial ‘Granting’ Independence 8 6 Adapted housing program for seriously disabled veterans is growing In Tribute to America’s National Shrines 11 Author publishes book on VA national cemeteries Celebrating Five Years of My HealtheVet 1 2 More than 500,000 users are now registered on VA’s Web health portal On the Cusp of a Breakthrough 14 Dr. David Vesely’s cancer research is showing real promise VA and the New Deal 16 8 WPA helped construct Baltimore National Cemetery Taking the Reins 18 An interview with new Secretary James B. Peake, M.D. The Dream Cutter 22 L.A. barber donates services to lift the spirits of his fellow veterans Helping Veterans on the ‘Road to Recovery’ 23 VA employees lend their expertise at Disney World event ‘Wreaths Across America’ 24 Veterans buried in national cemeteries remembered at the holidays 22 Celebrating the Holidays VA-Style 25 Holiday happenings at facilities around the country VAnguard VA’s Employee Magazine Departments January/February 2008 3 Feedback 30 Medical Advances Vol. LIV, No. 1 4 From the Secretary 31 Heroes Printed on 50% recycled paper 5 Outlook 32 Have You Heard 26 Around Headquarters 34 Honors Editor: Lisa Respess Gaegler Photo Editor: Robert Turtil 29 Introducing 36 Holiday Wreaths Photographer: Art Gardiner Staff Writer: Amanda Hester Published by the Office of Public Affairs (80D) U.S. -

The Korean War

N ATIO N AL A RCHIVES R ECORDS R ELATI N G TO The Korean War R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 1 0 3 COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 N AT I ONAL A R CH I VES R ECO R DS R ELAT I NG TO The Korean War COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 103 N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives records relating to the Korean War / compiled by Rebecca L. Collier.—Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2003. p. ; 23 cm.—(Reference information paper ; 103) 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration.—Catalogs. 2. Korean War, 1950-1953 — United States —Archival resources. I. Collier, Rebecca L. II. Title. COVER: ’‘Men of the 19th Infantry Regiment work their way over the snowy mountains about 10 miles north of Seoul, Korea, attempting to locate the enemy lines and positions, 01/03/1951.” (111-SC-355544) REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 103: NATIONAL ARCHIVES RECORDS RELATING TO THE KOREAN WAR Contents Preface ......................................................................................xi Part I INTRODUCTION SCOPE OF THE PAPER ........................................................................................................................1 OVERVIEW OF THE ISSUES .................................................................................................................1