Chapter 6: Electronic Structure of Atoms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Balmer Series

The Balmer Series Introduction Historically, the spectral lines of hydrogen have been categorized as six distinct series. The visible portion of the hydrogen spectrum is contained in the Balmer series, named after Johann Balmer who discovered an empirical relationship for calculating its wave- lengths [2]. In 1885 Balmer discovered that by labeling the four visible lines of the hydorgen spectrum with integers n, (n = 3, 4, 5, 6) (See Table 1 and Figure 1) each wavelength λ could be calculated from the relationship n2 λ = B , (1) n2 − 4 where B = 364.56 nm. Johannes Rydberg generalized Balmer’s result to include all of the wavelengths of the hydrogen spectrum. The Balmer formula is more commonly re–expressed in the form of the Rydberg formula 1 1 1 = RH − , (2) λ 22 n2 where n =3, 4, 5 . and the Rydberg constant RH =4/B. The purpose of this experiment is to determine the wavelengths of the visible spec- tral lines of hydrogen using a spectrometer and to calculate the Balmer constant B. Procedure The spectrometer used in this experiment is shown in Fig. 1. Adjust the diffraction grating so that the normal to its plane makes a small angle α to the incident beam of light. This is shown schematically in Fig. 2. Since α u 0, the angles between the first and zeroth order intensity maxima on either side, θ and θ0 respectively, are related to the wavelength λ of the incident light according to [1] λ = d sin(φ) , (3) accurate to first order in α. Here, d is the separation between the slits of the grating, and θ0 + θ φ = (4) 2 1 Color Wavelength [nm] Integer [n] Violet2 410.2 6 Violet1 434.0 5 blue 486.1 4 red 656.3 3 Table 1: The wavelengths and integer associations of the visible spectral lines of hy- drogen shown in Fig. -

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal Is to Define Electrons in Atoms

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal is to define electrons in atoms • Bohr Atom and Principal Energy Levels from “orbits”; Balance of electrostatic attraction and centripetal force: classical mechanics • Inability to account for emission lines => particle/wave description of atom and application of wave mechanics • Solutions of Schrodinger’s equation, Hψ = Eψ Required boundaries => quantum numbers (and the Pauli Exclusion Principle) • Electron configurations. C: 1s2 2s2 2p2 or [He]2s2 2p2 Na: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s1 or [Ne] 3s1 => Na+: [Ne] Cl: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s23p5 or [Ne]3s23p5 => Cl-: [Ne]3s23p6 or [Ar] What you already know: Quantum Numbers: n, l, ml , ms n is the principal quantum number, indicates the size of the orbital, has all positive integer values of 1 to ∞(infinity) (Bohr’s discrete orbits) l (angular momentum) orbital 0s l is the angular momentum quantum number, 1p represents the shape of the orbital, has integer values of (n – 1) to 0 2d 3f ml is the magnetic quantum number, represents the spatial direction of the orbital, can have integer values of -l to 0 to l Other terms: electron configuration, noble gas configuration, valence shell ms is the spin quantum number, has little physical meaning, can have values of either +1/2 or -1/2 Pauli Exclusion principle: no two electrons can have all four of the same quantum numbers in the same atom (Every electron has a unique set.) Hund’s Rule: when electrons are placed in a set of degenerate orbitals, the ground state has as many electrons as possible in different orbitals, and with parallel spin. -

Rydberg Constant and Emission Spectra of Gases

Page 1 of 10 Rydberg constant and emission spectra of gases ONE WEIGHT RECOMMENDED READINGS 1. R. Harris. Modern Physics, 2nd Ed. (2008). Sections 4.6, 7.3, 8.9. 2. Atomic Spectra line database https://physics.nist.gov/PhysRefData/ASD/lines_form.html OBJECTIVE - Calibrating a prism spectrometer to convert the scale readings in wavelengths of the emission spectral lines. - Identifying an "unknown" gas by measuring its spectral lines wavelengths. - Calculating the Rydberg constant RH. - Finding a separation of spectral lines in the yellow doublet of the sodium lamp spectrum. INSTRUCTOR’S EXPECTATIONS In the lab report it is expected to find the following parts: - Brief overview of the Bohr’s theory of hydrogen atom and main restrictions on its application. - Description of the setup including its main parts and their functions. - Description of the experiment procedure. - Table with readings of the vernier scale of the spectrometer and corresponding wavelengths of spectral lines of hydrogen and helium. - Calibration line for the function “wavelength vs reading” with explanation of the fitting procedure and values of the parameters of the fit with their uncertainties. - Calculated Rydberg constant with its uncertainty. - Description of the procedure of identification of the unknown gas and statement about the gas. - Calculating resolution of the spectrometer with the yellow doublet of sodium spectrum. INTRODUCTION In this experiment, linear emission spectra of discharge tubes are studied. The discharge tube is an evacuated glass tube filled with a gas or a vapor. There are two conductors – anode and cathode - soldered in the ends of the tube and connected to a high-voltage power source outside the tube. -

Rydberg Excitation of Single Atoms for Applications in Quantum Information and Metrology Aaron Hankin

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Physics & Astronomy ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1-28-2015 Rydberg Excitation of Single Atoms for Applications in Quantum Information and Metrology Aaron Hankin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/phyc_etds Recommended Citation Hankin, Aaron. "Rydberg Excitation of Single Atoms for Applications in Quantum Information and Metrology." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/phyc_etds/23 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics & Astronomy ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aaron Hankin Candidate Physics and Astronomy Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Ivan Deutsch , Chairperson Carlton Caves Keith Lidke Grant Biedermann Rydberg Excitation of Single Atoms for Applications in Quantum Information and Metrology by Aaron Michael Hankin B.A., Physics, North Central College, 2007 M.S., Physics, Central Michigan Univeristy, 2009 DISSERATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Physics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2014 iii c 2014, Aaron Michael Hankin iv Dedication To Maiko and our unborn daughter. \There are wonders enough out there without our inventing any." { Carl Sagan v Acknowledgments The experiment detailed in this manuscript evolved rapidly from an empty lab nearly four years ago to its current state. Needless to say, this is not something a graduate student could have accomplished so quickly by him or herself. -

23-Chapt-6-Quantum2

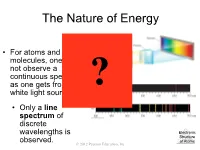

The Nature of Energy • For atoms and molecules, one does not observe a continuous spectrum, as one gets from a ? white light source. • Only a line spectrum of discrete wavelengths is Electronic Structure observed. of Atoms © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. The Players Erwin Schrodinger Werner Heisenberg Louis Victor De Broglie Neils Bohr Albert Einstein Max Planck James Clerk Maxwell Neils Bohr Explained the emission spectrum of the hydrogen atom on basis of quantization of electron energy. Neils Bohr Explained the emission spectrum of the hydrogen atom on basis of quantization of electron energy. Emission spectrum Emitted light is separated into component frequencies when passed through a prism. 397 410 434 486 656 wavelenth in nm Hydrogen, the simplest atom, produces the simplest emission spectrum. In the late 19th century a mathematical relationship was found between the visible spectral lines of hydrogen the group of hydrogen lines in the visible range is called the Balmer series 1 1 1 = R – λ ( 22 n2 ) Rydberg 1.0968 x 107m–1 Constant Johannes Rydberg Bohr Solution the electron circles nucleus in a circular orbit imposed quantum condition on electron energy only certain “orbits” allowed energy emitted is when electron moves from higher energy state (excited state) to lower energy state the lowest electron energy state is ground state ground state of hydrogen atom n = 5 n = 4 n = 3 n = 2 n = 1 e- excited state of hydrogen atom n = 5 n = 4 n = 3 e- n = 2 n = 1 hν excited state of hydrogen atom n = 5 n = 4 n = 3 n = 2 e- n = 1 hν excited state of hydrogen atom n = 5 n = 4 n = 3 e- n = 2 n = 1 hν Emission spectrum Emitted light is separated into component frequencies when passed through a prism. -

Density Functional Theory

Density Functional Theory Fundamentals Video V.i Density Functional Theory: New Developments Donald G. Truhlar Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota Support: AFOSR, NSF, EMSL Why is electronic structure theory important? Most of the information we want to know about chemistry is in the electron density and electronic energy. dipole moment, Born-Oppenheimer charge distribution, approximation 1927 ... potential energy surface molecular geometry barrier heights bond energies spectra How do we calculate the electronic structure? Example: electronic structure of benzene (42 electrons) Erwin Schrödinger 1925 — wave function theory All the information is contained in the wave function, an antisymmetric function of 126 coordinates and 42 electronic spin components. Theoretical Musings! ● Ψ is complicated. ● Difficult to interpret. ● Can we simplify things? 1/2 ● Ψ has strange units: (prob. density) , ● Can we not use a physical observable? ● What particular physical observable is useful? ● Physical observable that allows us to construct the Hamiltonian a priori. How do we calculate the electronic structure? Example: electronic structure of benzene (42 electrons) Erwin Schrödinger 1925 — wave function theory All the information is contained in the wave function, an antisymmetric function of 126 coordinates and 42 electronic spin components. Pierre Hohenberg and Walter Kohn 1964 — density functional theory All the information is contained in the density, a simple function of 3 coordinates. Electronic structure (continued) Erwin Schrödinger -

Electron Density Functions for Simple Molecules (Chemical Bonding/Excited States) RALPH G

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 77, No. 4, pp. 1725-1727, April 1980 Chemistry Electron density functions for simple molecules (chemical bonding/excited states) RALPH G. PEARSON AND WILLIAM E. PALKE Department of Chemistry, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93106 Contributed by Ralph G. Pearson, January 8, 1980 ABSTRACT Trial electron density functions have some If each component of the charge density is centered on a conceptual and computational advantages over wave functions. single point, the calculation of the potential energy is made The properties of some simple density functions for H+2 and H2 are examined. It appears that for a diatomic molecule a good much easier. However, the kinetic energy is often difficult to density function would be given by p = N(A2 + B2), in which calculate for densities containing several one-center terms. For A and B are short sums of s, p, d, etc. orbitals centered on each a wave function that is composed of one orbital, the kinetic nucleus. Some examples are also given for electron densities that energy can be written in terms of the electron density as are appropriate for excited states. T = 1/8 (VP)2dr [5] Primarily because of the work of Hohenberg, Kohn, and Sham p (1, 2), there has been great interest in studying quantum me- and in most cases this integral was evaluated numerically in chanical problems by using the electron density function rather cylindrical coordinates. The X integral was trivial in every case, than the wave function as a means of approach. Examples of and the z and r integrations were carried out via two-dimen- the use of the electron density include studies of chemical sional Gaussian bonding in molecules (3, 4), solid state properties (5), inter- quadrature. -

Chemistry 1000 Lecture 8: Multielectron Atoms

Chemistry 1000 Lecture 8: Multielectron atoms Marc R. Roussel September 14, 2018 Marc R. Roussel Multielectron atoms September 14, 2018 1 / 23 Spin Spin Spin (with associated quantum number s) is a type of angular momentum attached to a particle. Every particle of the same kind (e.g. every electron) has the same value of s. Two types of particles: Fermions: s is a half integer 1 Examples: electrons, protons, neutrons (s = 2 ) Bosons: s is an integer Example: photons (s = 1) Marc R. Roussel Multielectron atoms September 14, 2018 2 / 23 Spin Spin magnetic quantum number All types of angular momentum obey similar rules. There is a spin magnetic quantum number ms which gives the z component of the spin angular momentum vector: Sz = ms ~ The value of ms can be −s; −s + 1;:::; s. 1 1 1 For electrons, s = 2 so ms can only take the values − 2 or 2 . Marc R. Roussel Multielectron atoms September 14, 2018 3 / 23 Spin Stern-Gerlach experiment How do we know that electrons (e.g.) have spin? Source: Theresa Knott, Wikimedia Commons, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Stern-Gerlach_experiment.PNG Marc R. Roussel Multielectron atoms September 14, 2018 4 / 23 Spin Pauli exclusion principle No two fermions can share a set of quantum numbers. Marc R. Roussel Multielectron atoms September 14, 2018 5 / 23 Multielectron atoms Multielectron atoms Electrons occupy orbitals similar (in shape and angular momentum) to those of hydrogen. Same orbital names used, e.g. 1s, 2px , etc. The number of orbitals of each type is still set by the number of possible values of m`, so e.g. -

“Band Structure” for Electronic Structure Description

www.fhi-berlin.mpg.de Fundamentals of heterogeneous catalysis The very basics of “band structure” for electronic structure description R. Schlögl www.fhi-berlin.mpg.de 1 Disclaimer www.fhi-berlin.mpg.de • This lecture is a qualitative introduction into the concept of electronic structure descriptions different from “chemical bonds”. • No mathematics, unfortunately not rigorous. • For real understanding read texts on solid state physics. • Hellwege, Marfunin, Ibach+Lüth • The intention is to give an impression about concepts of electronic structure theory of solids. 2 Electronic structure www.fhi-berlin.mpg.de • For chemists well described by Lewis formalism. • “chemical bonds”. • Theorists derive chemical bonding from interaction of atoms with all their electrons. • Quantum chemistry with fundamentally different approaches: – DFT (density functional theory), see introduction in this series – Wavefunction-based (many variants). • All solve the Schrödinger equation. • Arrive at description of energetics and geometry of atomic arrangements; “molecules” or unit cells. 3 Catalysis and energy structure www.fhi-berlin.mpg.de • The surface of a solid is traditionally not described by electronic structure theory: • No periodicity with the bulk: cluster or slab models. • Bulk structure infinite periodically and defect-free. • Surface electronic structure theory independent field of research with similar basics. • Never assume to explain reactivity with bulk electronic structure: accuracy, model assumptions, termination issue. • But: electronic -

Simple Molecular Orbital Theory Chapter 5

Simple Molecular Orbital Theory Chapter 5 Wednesday, October 7, 2015 Using Symmetry: Molecular Orbitals One approach to understanding the electronic structure of molecules is called Molecular Orbital Theory. • MO theory assumes that the valence electrons of the atoms within a molecule become the valence electrons of the entire molecule. • Molecular orbitals are constructed by taking linear combinations of the valence orbitals of atoms within the molecule. For example, consider H2: 1s + 1s + • Symmetry will allow us to treat more complex molecules by helping us to determine which AOs combine to make MOs LCAO MO Theory MO Math for Diatomic Molecules 1 2 A ------ B Each MO may be written as an LCAO: cc11 2 2 Since the probability density is given by the square of the wavefunction: probability of finding the ditto atom B overlap term, important electron close to atom A between the atoms MO Math for Diatomic Molecules 1 1 S The individual AOs are normalized: 100% probability of finding electron somewhere for each free atom MO Math for Homonuclear Diatomic Molecules For two identical AOs on identical atoms, the electrons are equally shared, so: 22 cc11 2 2 cc12 In other words: cc12 So we have two MOs from the two AOs: c ,1() 1 2 c ,1() 1 2 2 2 After normalization (setting d 1 and _ d 1 ): 1 1 () () [2(1 S )]1/2 12 [2(1 S )]1/2 12 where S is the overlap integral: 01 S LCAO MO Energy Diagram for H2 H2 molecule: two 1s atomic orbitals combine to make one bonding and one antibonding molecular orbital. -

Electron Charge Density: a Clue from Quantum Chemistry for Quantum Foundations

Electron Charge Density: A Clue from Quantum Chemistry for Quantum Foundations Charles T. Sebens California Institute of Technology arXiv v.2 June 24, 2021 Forthcoming in Foundations of Physics Abstract Within quantum chemistry, the electron clouds that surround nuclei in atoms and molecules are sometimes treated as clouds of probability and sometimes as clouds of charge. These two roles, tracing back to Schr¨odingerand Born, are in tension with one another but are not incompatible. Schr¨odinger'sidea that the nucleus of an atom is surrounded by a spread-out electron charge density is supported by a variety of evidence from quantum chemistry, including two methods that are used to determine atomic and molecular structure: the Hartree-Fock method and density functional theory. Taking this evidence as a clue to the foundations of quantum physics, Schr¨odinger'selectron charge density can be incorporated into many different interpretations of quantum mechanics (and extensions of such interpretations to quantum field theory). Contents 1 Introduction2 2 Probability Density and Charge Density3 3 Charge Density in Quantum Chemistry9 3.1 The Hartree-Fock Method . 10 arXiv:2105.11988v2 [quant-ph] 24 Jun 2021 3.2 Density Functional Theory . 20 3.3 Further Evidence . 25 4 Charge Density in Quantum Foundations 26 4.1 GRW Theory . 26 4.2 The Many-Worlds Interpretation . 29 4.3 Bohmian Mechanics and Other Particle Interpretations . 31 4.4 Quantum Field Theory . 33 5 Conclusion 35 1 1 Introduction Despite the massive progress that has been made in physics, the composition of the atom remains unsettled. J. J. Thomson [1] famously advocated a \plum pudding" model where electrons are seen as tiny negative charges inside a sphere of uniformly distributed positive charge (like the raisins|once called \plums"|suspended in a plum pudding). -

Nature of Noncovalent Carbon-Bonding Interactions Derived from Experimental Charge-Density Analysis

Nature of Noncovalent Carbon-Bonding Interactions Derived from Experimental Charge-Density Analysis Eduardo C. Escudero-Adán, Antonio Bauzffl, Antonio Frontera, and Pablo Ballester E. C. Escudero-Adán,+ Prof. P. Ballester X-Ray Diffraction Unit Institute of Chemical Research of Catalonia (ICIQ) Avgda. Països Catalans 16, 43007 Tarragona (Spain) E-mail : [email protected] A. Bauzffl,+ Prof. A. Frontera Department of Chemistry Universitat de les Illes Balears Crta. de Valldemossa km 7.5, 07122 Palma de Mallorca (Spain) E-mail : [email protected] Prof. P. Ballester Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA) Passeig Lluïs Companys 23, 08010 Barcelona (Spain) In an effort to better understand the nature of noncovalent carbon-bonding interactions, we undertook accurate high-res- olution X-ray diffraction analysis of single crystals of 1,1,2,2-tet- racyanocyclopropane. We selected this compound to study the fundamental characteristics of carbon-bonding interactions, because it provides accessible s holes. The study required ex- tremely accurate experimental diffraction data, because the in- teraction of interest is weak. The electron-density distribution around the carbon nuclei, as shown by the experimental maps of the electrophilic bowl defined by a (CN)2C-C(CN)2 unit, was assigned as the origin of the interaction. This fact was also evidenced by plotting the D21(r) distribution. Taken together, the obtained results clearly indicate that noncovalent carbon bonding can be explained as an interaction between confront- ed oppositely polarized regions. The interaction is, thus elec- trophilic–nucleophilic (electrostatic) in nature and unambigu- ously considered as attractive. Attractive intermolecular electrostatic interactions encompass electron-rich and electron-poor regions of two molecules that complement each other.[1] Electron-rich entities are typically anions or lone-pair electrons and the most well-known elec- tron-poor entity is the hydrogen atom.