Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leonard Bernstein's Piano Music: a Comparative Study of Selected Works

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 Leonard Bernstein's Piano Music: A Comparative Study of Selected Works Leann Osterkamp The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2572 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LEONARD BERNSTEIN’S PIANO MUSIC: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF SELECTED WORKS by LEANN OSTERKAMP A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2018 ©2018 LEANN OSTERKAMP All Rights Reserved ii Leonard Bernstein’s Piano Music: A Comparative Study of Selected Works by Leann Osterkamp This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Date Ursula Oppens Chair of Examining Committee Date Norman Carey Executive Director Supervisory Committee Dr. Jeffrey Taylor, Advisor Dr. Philip Lambert, First Reader Michael Barrett, Second Reader THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Leonard Bernstein’s Piano Music: A Comparative Study of Selected Works by Leann Osterkamp Advisor: Dr. Jeffrey Taylor Much of Leonard Bernstein’s piano music is incorporated in his orchestral and theatrical works. The comparison and understanding of how the piano works relate to the orchestral manifestations validates the independence of the piano works, provides new insights into Bernstein’s compositional process, and presents several significant issues of notation and interpretation that can influence the performance practice of both musical versions. -

Composition Catalog

1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 New York Content & Review Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Marie Carter Table of Contents 229 West 28th St, 11th Floor Trudy Chan New York, NY 10001 Patrick Gullo 2 A Welcoming USA Steven Lankenau +1 (212) 358-5300 4 Introduction (English) [email protected] Introduction 8 Introduction (Español) www.boosey.com Carol J. Oja 11 Introduction (Deutsch) The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Translations 14 A Leonard Bernstein Timeline 121 West 27th St, Suite 1104 Straker Translations New York, NY 10001 Jens Luckwaldt 16 Orchestras Conducted by Bernstein USA Dr. Kerstin Schüssler-Bach 18 Abbreviations +1 (212) 315-0640 Sebastián Zubieta [email protected] 21 Works www.leonardbernstein.com Art Direction & Design 22 Stage Kristin Spix Design 36 Ballet London Iris A. Brown Design Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited 36 Full Orchestra Aldwych House Printing & Packaging 38 Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra 71-91 Aldwych UNIMAC Graphics London, WC2B 4HN 40 Voice(s) & Orchestra UK Cover Photograph 42 Ensemble & Chamber without Voice(s) +44 (20) 7054 7200 Alfred Eisenstaedt [email protected] 43 Ensemble & Chamber with Voice(s) www.boosey.com Special thanks to The Leonard Bernstein 45 Chorus & Orchestra Office, The Craig Urquhart Office, and the Berlin Library of Congress 46 Piano(s) Boosey & Hawkes • Bote & Bock GmbH 46 Band Lützowufer 26 The “g-clef in letter B” logo is a trademark of 47 Songs in a Theatrical Style 10787 Berlin Amberson Holdings LLC. Deutschland 47 Songs Written for Shows +49 (30) 2500 13-0 2015 & © Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. 48 Vocal [email protected] www.boosey.de 48 Choral 49 Instrumental 50 Chronological List of Compositions 52 CD Track Listing LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 2 3 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 A Welcoming Leonard Bernstein’s essential approach to music was one of celebration; it was about making the most of all that was beautiful in sound. -

American Mavericks Festival

VISIONARIES PIONEERS ICONOCLASTS A LOOK AT 20TH-CENTURY MUSIC IN THE UNITED STATES, FROM THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY EDITED BY SUSAN KEY AND LARRY ROTHE PUBLISHED IN COOPERATION WITH THE UNIVERSITY OF CaLIFORNIA PRESS The San Francisco Symphony TO PHYLLIS WAttIs— San Francisco, California FRIEND OF THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, CHAMPION OF NEW AND UNUSUAL MUSIC, All inquiries about the sales and distribution of this volume should be directed to the University of California Press. BENEFACTOR OF THE AMERICAN MAVERICKS FESTIVAL, FREE SPIRIT, CATALYST, AND MUSE. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England ©2001 by The San Francisco Symphony ISBN 0-520-23304-2 (cloth) Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI / NISO Z390.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). Printed in Canada Designed by i4 Design, Sausalito, California Back cover: Detail from score of Earle Brown’s Cross Sections and Color Fields. 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 v Contents vii From the Editors When Michael Tilson Thomas announced that he intended to devote three weeks in June 2000 to a survey of some of the 20th century’s most radical American composers, those of us associated with the San Francisco Symphony held our breaths. The Symphony has never apologized for its commitment to new music, but American orchestras have to deal with economic realities. For the San Francisco Symphony, as for its siblings across the country, the guiding principle of programming has always been balance. -

Decca Discography

DECCA DISCOGRAPHY >>V VIENNA, Austria, Germany, Hungary, etc. The Vienna Philharmonic was the jewel in Decca’s crown, particularly from 1956 when the engineers adopted the Sofiensaal as their favoured studio. The contract with the orchestra was secured partly by cultivating various chamber ensembles drawn from its membership. Vienna was favoured for symphonic cycles, particularly in the mid-1960s, and for German opera and operetta, including Strausses of all varieties and Solti’s “Ring” (1958-65), as well as Mackerras’s Janá ček (1976-82). Karajan recorded intermittently for Decca with the VPO from 1959-78. But apart from the New Year concerts, resumed in 2008, recording with the VPO ceased in 1998. Outside the capital there were various sessions in Salzburg from 1984-99. Germany was largely left to Decca’s partner Telefunken, though it was so overshadowed by Deutsche Grammophon and EMI Electrola that few of its products were marketed in the UK, with even those soon relegated to a cheap label. It later signed Harnoncourt and eventually became part of the competition, joining Warner Classics in 1990. Decca did venture to Bayreuth in 1951, ’53 and ’55 but wrecking tactics by Walter Legge blocked the release of several recordings for half a century. The Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra’s sessions moved from Geneva to its home town in 1963 and continued there until 1985. The exiled Philharmonia Hungarica recorded in West Germany from 1969-75. There were a few engagements with the Bavarian Radio in Munich from 1977- 82, but the first substantial contract with a German symphony orchestra did not come until 1982. -

Rattle Opens Berlin Season with Lindberg

QNotes 72 (23-9) 24/9/07 5:20 pm Page 2 Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited October 2007 2007/3 Carter Included in this issue: Rattle opens Berlin towards 2008 Chin Elliott Carter celebrates his 100th birthday on Munich premieres Alice 11 December 2008 and plans are in place in Wonderland opera season with Lindberg for international celebrations, featuring the most recently completed scores by this elder statesman among Magnus Lindberg’s new master. Adopting its title from the final “Again and again the huge orchestra releases American sunrise chorus of Schoenberg’s epic cantata bolts of energy… Lindberg’s sun does not smile orchestral work, Seht die mildly upon its worshippers. Instead, it fires up the composers. Major Gurrelieder, the work explores the tipping birthday events are Sonne, provided a dramatic point from late-Romanticism to modernism. music and lends it a lasting resplendence.” Berliner Morgenpost so far confirmed in Boston, New York, opening to the Berliner “…an extravagant and glittering piece on a grand London, Paris, Philharmoniker’s season. “Sharp as a knife – scale, full of bold gestures and big effects… The second movement ends with a solo cello cadenza Berlin, Cologne, a tour de force”Der Tagesspiegel Following the August premiere of Seht die so lengthy that it is almost a miniature concerto, a Amsterdam, Turin, Sonne, commissioned by the Stiftung mournful lament full of ethereal harmonics. The Basel, Vienna, “…a work that liberally mixes the exquisite colours third movement is the work’s darkest, opening in Lisbon, Porto and Berliner Philharmoniker in association with of the orchestra… and that in its luminescent the San Francisco Symphony, Simon Rattle the lower depths of the bass registers and rising Photo: Meredith Heuer Gothenburg. -

Roch Voisine Chrlstma4 Ls Calling

Volume 71 No. 26 November 6, 2000 BULLETS, LOVE & BEER ON BRAVO Stan Klees as Harry Cotton shown with co-star. See page 4 NEW EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] $3.00 ($2.80 plus .20 GST) Publication Mail Registration No.08141 Roch Voisine ChrLstma4 Ls calling ROCILMOSINE 2- RPM - Monday November 6, 2000 Theatre du Quebec (20). The tour concludes with Roch Voisine returns with new holiday album three shows at the Theatre St-Denis in Montreal November 7 is the street date for Roch Voisine's Kitchener's Centre-In-The-Square (7), Massey Hall (Dec. 21, 22 and 23). first-ever holiday release. Christmas Is Calling, in Toronto (8), Hamilton Place (10), Ottawa's Also, CBC Television will air a special featuring ahost of holiday favourites, is Voisine's National Arts Centre (11), Caraquet, New Brunswick featuring Voisine, titled Christmas Is Calling, on first release via his own RV International label since (15), Metro Centre in Halifax (16), and the Grand December 17. the double-platinum-plus Kissing Rain. RV International is distributed in Canada by BMG. Bertelsmann breaks ranks to join with Napster Songs featured on the release include Silent German media giant Bertelsmann AG, the parent which at last count was upwards of 38 million users. Night, White Christmas, Winter Wonderland, Joy company of BMG Music, has gone against the The move marks a dramatic reversal for the To The World, Sleigh Ride, Little Drummer Boy, record industry grain and forged an alliance with media giant, who had previously been part of a I'll Be Home For Christmas, 0 Christmas Tree, The music-swapping service Napster Inc. -

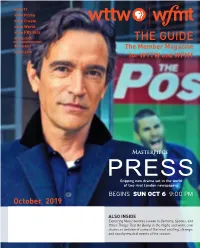

Inside the Guide the Guide

wttw11 wttw Prime wttw Create wttw World wttw PBS Kids wttw.com THE GUIDE 98.7wfmt The Member Magazine wfmt.com for WTTW and WFMT Gripping new drama set in the world of two rival London newspapers BEGINS SUN OCT 6 9:00 PM October 2019 ALSO INSIDE Exploring Music devotes a week to Demons, Spooks, and Other Things That Go Bump in the Night; and wfmt.com shares a rundown of some of the most exciting, strange, and spooky musical events of the season. From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center Independent, unbiased, and trusted news is essential to a high-functioning 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 democracy. In that context, WTTW is excited to bring you Press, a new six-part British drama series that explores the turbulent media landscape and the ethical Main Switchboard dilemmas journalists face each day. Join us on Sundays after Durrells in Corfu (773) 583-5000 and Poldark for this story of two rival newspapers struggling to compete in a Member and Viewer Services (773) 509-1111 x 6 24-hour news cycle. Also on WTTW, Check, Please! returns for a 19th season with host Alpana Websites Singh and our citizen reviewers who will take you on a journey of tastes and wttw.com wfmt.com neighborhoods. NOVA explores Why Bridges Collapse; and the new magazine series Retro Report on PBS connects our present with our past. On wttw.com, Publisher move beyond the myths and discover the true story of the infamous Black Sox Anne Gleason scandal on its centennial. -

Spring/Summer 2009 IU's Jacobs School of Music Receives Bernstein Gift

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Spring/Summer 2009 IU's Jacobs School of Music Receives Bernstein Gift by Craig Urquhart he Family of Leonard Bernstein has given Indiana University's Jacobs School of Music the contents of Leonard Bernstein's Fairfield, Connecticut, composing studio. "We are honored to receive this gift which follows a rich collaborative and professional relationship between the Bernstein family and the Jacobs School that began in the early 1970s," said Gwyn Richards, Dean of the Jacobs School of Music. "In a real sense Leonard Bernstein connected with our School and its leadership, and it is thrilling to know that the link with Indiana continues and is strengthened through this remarkable gesture." "My father's artistic and edu cational connection with Indiana University was very strong," said Leonard's son, Alexander Bernstein. "He adored the institution and became close to the Dean, its faculty and, of course, its students. My sisters, Jamie and Nina, join me in celebrating the continuation of this relationship by literally bringing together two of the places in which he was happiest (continued on page 2) Leonard Bernstein's Fairfield studio wall West Side Story Takes Leonard Bernstein's 9 My Friend Schuyler Inside ... Over Broadway! Peter Pan Flies Again 10 In the News Leonard Bernstein and in Santa Barbara 12 Some Performances Felix Mendelssohn Jacobs School of Music Receives To Our Bernstein Gift, continued working. We cannot imagine a more fitting home for this exciting Readers new representation of Leonard Bernstein's working life." The Jacobs School plans to recreate Leonard Bernstein's working environment, which will outh, fame and fortune come and contain the items in the collection go, but music lives on forever - Y and be used as a teaching studio and a good thing, too. -

May 2005 Volume 10, Issue 8

www.tcago.org May 2005 Volume 10, Issue 8 AMERICAN GUILD OF ORGANISTS—TWIN CITIES CHAPTER A Cameron Carpenter TCAGO PROGRAM SCHEDULE Recital PLUS! 2005 by Diana Lee Lucker MAY n addition to his recital at 7:30 pm on Tuesday, May Mon. May 9, 4:00 pm Program for Young People I 10, Cameron Carpenter will with Cameron Carpenter, Wayzata Community Church present a program for young peo- ple at 4:00 pm on Monday May 9 Tues. May 10, 7:30 pm Organ Recital at Wayzata Community Church. Cameron Carpenter, organist Cameron has become famous for Wayzata Community Church concert series his ability to engage, attract and inspire young people to the organ. Fri., May 13, 7:30 pm The program is open to all, how- Competition Winners’ Recital ever young people will be encour- Wayzata Community Church aged to attend. This gifted flam- boyant young performer has been taking the nation by storm. His JUNE Board the Boat Boat Cruise on Lake Minnetonka Mon. June 13, 6:30-9:30pm INSIDE THIS ISSUE TCAGO members and a guest Page 1 Cameron $10 per person (paid upon boarding) Carpenter Program and potluck supper, cash bar Recital RSVP by June 8 to Paul Lohman Ph: 612-827-3625 [email protected] Page 5 Archive News Page 6 Gary Miller Organ Recital Page 9 Many Voices fresh approach to standard literature and his phenomenal and quite amazing technique and his improvisational skill are abso- One Minnesota lutely amazing. At age 23, his belief in highly individualized performance and his adaptation of certain elements of perform- Page 10 German ance art into classical music, have made him a controversial Choir Performs at St. -

Spring/Summer 2005

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Summer/Spring 2005 An Accolade for One Helluva Show by Richard Morrison As Lu11do11 welcomed back the pz,ergreen musical On the Town, the limes talks to lyricist Bctt)' Comden. any writers have captured something The Creative Team of the spirit of of On the Town New York. But in an apartment high above the Leonard Bernstein, bustle of her beloved Broadway Jerome Robbins, sits a frail 89-year-old woman who defined the city for a genera Betty Comden, and tion. Sixty-one years ago, Betty Adolph Green. 1944 Comden sat down with her writing partner, Adolph Green, in a little room just two blocks from where she now lives, and encapsulated the frenetic swirl of the great metropolis in one of the most evocative quatrains ever penned: New York, New York, a helluva town. The Bronx is up but the Battery's down, The people ideas, wrote the lyrics," she says. 24 hours' leave to explore its ride in a hole in the groun'; "We had complementary minds. delights. As Comden says: New York, New York, The same kind of humour, the "New York's streets were full it's a helluva town. same views. But as I had foolishly of servicemen, all searching for learnt to type, I was the one who joy before being sent into the Whether it was Comden or had to write it all down." war. We wanted to capture the Green who came up with these What she typed in the summer poignancy of those times." pulsating lines will never be of 1944 were the opening words Comden knew at first hand of known. -

October 2005

21ST CENTURY MUSIC OCTOBER 2005 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $84.00 per year; subscribers elsewhere should add $36.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $10.00. Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. email: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2005 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Typescripts should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors with access to IBM compatible word-processing systems are encouraged to submit a floppy disk, or e-mail, in addition to hard copy. -

Hired Gunns Dynamic Duo Joins Music Faculty

WINTER 2008 The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music Hired Gunns Dynamic Duo Joins Music Faculty Bruno Nettl: Early Ethnomusicology at Illinois Sheila C. Johnson: Exploring the Spaces Between the Notes Remembering Jerry Hadley From the Dean It is a pleasure for me to welcome you to this edition of sonorities, the WINTER 2008 news magazine of the School of Published for alumni and friends of the School of Music at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Music at the University of Illinois at The School of Music is a unit of the College of Fine Urbana-Champaign. and Applied Arts at the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign and has been an accredited institutional This past year has been one of member of the National Association of Schools of Music since 1933. incredible growth and accomplishments in the School of Music. Apart from Karl Kramer, director Edward Rath, associate director outstanding recitals and concerts given by faculty and students each year here Marlah Bonner-McDuffie, associate director, development in Urbana-Champaign, this past summer the School participated in such excit- David Atwater, assistant director, business Joyce Griggs, assistant director, enrollment management ing projects as the Burgos Chamber Music Festival in Burgos, Spain, and the and public engagement David Allen, coordinator, outreach and public engagement inaugural Allerton Music Barn Festival in nearby Monticello, Illinois. And in Michael Cameron, coordinator, graduate studies the spring, Chancellor Richard Herman and the Sinfonia da Camera made a B. Suzanne Hassler, coordinator, alumni relations and development successful tour of China, serving as important ambassadors for the University.