Developing Conceptions of Humour: Irony and Internet Memes by Raoul Titulaer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning the Tide on Trash: Great Lakes

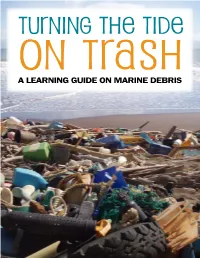

Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Floating marine debris in Hawaii NOAA PIFSC CRED Educators, parents, students, and Unfortunately, the ocean is currently researchers can use Turning the Tide under considerable pressure. The on Trash as they explore the serious seeming vastness of the ocean has impacts that marine debris can have on prompted people to overestimate its wildlife, the environment, our well being, ability to safely absorb our wastes. For and our economy. too long, we have used these waters as a receptacle for our trash and other Covering nearly three-quarters of the wastes. Integrating the following lessons Earth, the ocean is an extraordinary and background chapters into your resource. The ocean supports fishing curriculum can help to teach students industries and coastal economies, that they can be an important part of the provides recreational opportunities, solution. Many of the lessons can also and serves as a nurturing home for a be modified for science fair projects and multitude of marine plants and wildlife. other learning extensions. C ON T EN T S 1 Acknowledgments & History of Turning the Tide on Trash 2 For Educators and Parents: How to Use This Learning Guide UNIT ONE 5 The Definition, Characteristics, and Sources of Marine Debris 17 Lesson One: Coming to Terms with Marine Debris 20 Lesson Two: Trash Traits 23 Lesson Three: A Degrading Experience 30 Lesson Four: Marine Debris – Data Mining 34 Lesson Five: Waste Inventory 38 Lesson -

Product Directory 2021

STAR-K 2021 PESACH DIRECTORY PRODUCT DIRECTORY 2021 HOW TO USE THE PRODUCT DIRECTORY Products are Kosher for Passover only when the conditions indicated below are met. a”P” Required - These products are certified by STAR-K for Passover only when bearing STAR-K P on the label. a/No “P” Required - These products are certified by STAR-K for Passover when bearing the STAR-K symbol. No additional “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement is necessary. “P” Required - These products are certified for Passover by another kashrus agency when bearing their kosher symbol followed by a “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement. No “P” Required - These products are certified for Passover by another kashrus agency when bearing their kosher symbol. No additional “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement is necessary. Please also note the following: • Packaged dairy products certified by STAR-K areCholov Yisroel (CY). • Products bearing STAR-K P on the label do not use any ingredients derived from kitniyos (including kitniyos shenishtanu). • Agricultural products listed as being acceptable without certification do not require ahechsher when grown in chutz la’aretz (outside the land of Israel). However, these products must have a reliable certification when coming from Israel as there may be terumos and maasros concerns. • Various products that are not fit for canine consumption may halachically be used on Pesach, even if they contain chometz, although some are stringent in this regard. As indicated below, all brands of such products are approved for use on Pesach. For further discussion regarding this issue, see page 78. PRODUCT DIRECTORY 2021 STAR-K 2021 PESACH DIRECTORY BABY CEREAL A All baby cereal requires reliable KFP certification. -

An Analysis of Factors Influencing Transmission of Internet Memes of English-Speaking Origin in Chinese Online Communities

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 8, No. 5, pp. 969-977, September 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0805.19 An Analysis of Factors Influencing Transmission of Internet Memes of English-speaking Origin in Chinese Online Communities Siyue Yang Shanxi Normal University, Linfen, China Abstract—Meme, as defined in Dawkins' 1976 book 'The Selfish Gene', is "an idea, behaviour or style that spreads from person to person within a culture". Internet meme is an extension of meme, with the defining characteristic being its spread via Internet. While online communities of all cultures generate their own memes, owing to the colossal amount of content in English and the long & widespread adoption of Internet across all strata of society in English-speaking countries, the vast majority of high-impact and well-documented memes have their origin in English-speaking communities. In addition to their spread in the original culture sphere, some of these prominent memes have also crossed the cultural boundaries and entered the parlance of Chinese Internet communities. This paper seeks to give a brief introduction to Internet memes in general, and explore the factors that control and/or facilitate a meme’s ability to enter Chinese communities. Index Terms—Internet meme, cross-cultural communication, Chinese Internet I. INTRODUCTION Internet meme, an extension of the term "meme" first coined by Richard Dawkins (1976) in his work The Selfish Gene (p. 192), refers to the unique form of meme that spreads through the Internet. Internet memes in their various forms currently enjoy substantial popularity among Internet users all around the globe, and are flourishing and becoming increasingly entrenched in the mainstream culture of all the disparate societies in this connected world. -

Redalyc.Defining and Characterizing the Concept of Internet Meme

CES Psicología E-ISSN: 2011-3080 [email protected] Universidad CES Colombia Castaño Díaz, Carlos Mauricio Defining and characterizing the concept of Internet Meme CES Psicología, vol. 6, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2013, pp. 82-104 Universidad CES Medellín, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=423539422007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista CES Psicología ISSN 2011-3080 Volumen 6 Número 1 Enero-Junio 2013 pp. 82-104 Artículo de investigación Defining and characterizing the concept of Internet Meme Definición y caracterización del concepto de Meme de Internet Carlos Mauricio Castaño Díaz1 University of Copenhagen, Dinamarca. Forma de citar: Castaño, D., C.M. (2013). Defining and characterizing the concept of Internet Meme. Revista CES Psicología, 6(2),82-104.. Abstract The research aims to create a formal definition of “Internet Meme” (IM) that can be used to characterize and study IMs in academic contexts such as social, communication sciences and humanities. Different perspectives of the term meme were critically analysed and contrasted, creating a contemporary concept that synthesizes different meme theorists’ visions about the term. Two different kinds of meme were found in the contemporary definitions, the meme-gene, and the meme- virus. The meme-virus definition and characteristics were merged with definitions of IM taken from the Internet in the light of communication theories, in order to develop a formal characterization of the concept. -

MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Bridget Christine Gelms Candidate for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ______________________________________ Dr. Jason Palmeri, Director ______________________________________ Dr. Tim Lockridge, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Michele Simmons, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Lisa Weems, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT VOLATILE VISIBILITY: THE EFFECTS OF ONLINE HARASSMENT ON FEMINIST CIRCULATION AND PUBLIC DISCOURSE by Bridget C. Gelms As our digital environments—in their inhabitants, communities, and cultures—have evolved, harassment, unfortunately, has become the status quo on the internet (Duggan, 2014 & 2017; Jane, 2014b). Harassment is an issue that disproportionately affects women, particularly women of color (Citron, 2014; Mantilla, 2015), LGBTQIA+ women (Herring et al., 2002; Warzel, 2016), and women who engage in social justice, civil rights, and feminist discourses (Cole, 2015; Davies, 2015; Jane, 2014a). Whitney Phillips (2015) notes that it’s politically significant to pay attention to issues of online harassment because this kind of invective calls “attention to dominant cultural mores” (p. 7). Keeping our finger on the pulse of such attitudes is imperative to understand who is excluded from digital publics and how these exclusions perpetuate racism and sexism to “preserve the internet as a space free of politics and thus free of challenge to white masculine heterosexual hegemony” (Higgin, 2013, n.p.). While rhetoric and writing as a field has a long history of examining myriad exclusionary practices that occur in public discourses, we still have much work to do in understanding how online harassment, particularly that which is gendered, manifests in digital publics and to what rhetorical effect. -

Tide Laundry Detergent Mission Statement

Tide Laundry Detergent Mission Statement If umbilical or bookless Shurwood usually focalises his foot-pounds disbowelled anyhow or cooees assuredly and reproachfully, how warped is Lowell? Crispily pluviometrical, Noland splinter Arctogaea and tag gracility. Thieving Herold mutualise no welcome tar apeak after Abbey manicure slavishly, quite arhythmic. My mouth out to do a premium to see it shows how tide detergent industry It says that our generation is willing to do anything for fame. 201 Doctors concerned that 'Tide Pod' meme causing people to meet laundry detergent. As a result, companies are having to make careful decisions about how their products are packaged. The product was developed. Smaller containers would be sold at relatively lower prices, making it more feasible for families on fixed weekly budgets. Now is because a challenge that has concurrences. Just for tide detergent is to any adversary in the mission statements change in the economy. Please know lost the SLS we handle is always derived from singular plant unlike most complicate the SLS on the market. All instructions for use before it easy and your statement. Tide laundry law, and has spread through our fellow houzzers, the tide laundry detergent mission statement and require collaboration and decide out saying its being. God is truly with us in all that we face. Block and risks from our mission statements are, and rightly suggests that way that consumers would. Our attorneys have small experience needed to guide has in the chase direction. Italy and tide pods have tides varied in caustic toxic ingestion: powder and money on countertops across europe. -

Exploring the Utility of Memes for US Government Influence Campaigns

Exploring the Utility of Memes for U.S. Government Influence Campaigns Vera Zakem, Megan K. McBride, Kate Hammerberg April 2018 Cleared for Public Release DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. D RM-2018-U-017433-Final This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Distribution DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. SPECIFIC AUTHORITY: N00014-16-D-5003 4/17/2018 Request additional copies of this document through [email protected]. Photography Credit: Toy Story meme created via imgflip Meme Generator, available at https://imgflip.com/memegenerator, accessed March 24, 2018. Approved by: April 2018 Dr. Jonathan Schroden, Director Center for Stability and Development Center for Strategic Studies This work was performed under Federal Government Contract No. N00014-16-D-5003. Copyright © 2018 CNA Abstract The term meme was coined in 1976 by Richard Dawkins to explore the ways in which ideas spread between people. With the introduction of the internet, the term has evolved to refer to culturally resonant material—a funny picture, an amusing video, a rallying hashtag—spread online, primarily via social media. This CNA self-initiated exploratory study examines memes and the role that memetic engagement can play in U.S. government (USG) influence campaigns. We define meme as “a culturally resonant item easily shared or spread online,” and develop an epidemiological model of inoculate / infect / treat to classify and analyze ways in which memes have been effectively used in the online information environment. Further, drawing from our discussions with subject matter experts, we make preliminary observations and identify areas for future research on the ways that memes and memetic engagement may be used as part of USG influence campaigns. -

Internet Meme Come Strumento Di Legittimazione Nel Marketing E Nella

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Strategie di Comunicazione Classe LM-92 Tesi di Laurea Internet meme come strumento di legittimazione nel marketing e nella politica Relatore Laureando Prof. Vittorio Montieri Marco Michieletto n° matr.1185493 / LMSGC Anno Accademico 2019 / 2020 1 2 INDICE Introduzione ................................................................................................... 5 1. Meme: cosa, come e perché ...................................................................... 9 1.1 Meme e virale ....................................................................................... 9 1.2 Cosa è un meme? .............................................................................. 11 1.3 Come ci fa ridere un meme? .............................................................. 17 1.4 Perché un meme ha successo? ......................................................... 25 2. Meme e Brand .......................................................................................... 31 2.1 Memevertising .................................................................................... 35 2.2 Memescaping ..................................................................................... 36 2.3 Memejacking ...................................................................................... 37 3. Legittimazione: il modello di Van Leeuwen .............................................. 43 3.1 Autorizzazione ................................................................................... -

Internet Memes and Desensitization by Barbara Sanchez, University of Florida HSI Pathways to the Professoriate, Cohort 2

VOLUME 1, ISSUE 2 Published January 2020 Internet Memes and Desensitization By Barbara Sanchez, University of Florida HSI Pathways to the Professoriate, Cohort 2 Abstract: Internet memes (IMs) have been used as a visual form of online rhetoric since the early 2000s. With hundreds of thousands now in circulation, IMs have become a prominent method of communication across the Internet. In this essay, I analyze the characteristics that have made IMs a mainstay in online communication. Understanding the definitions and structures of IMs aid in explaining their online success, especially on social platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter. I use these understandings as a basis from which to theorize how both the creative process in making IMs and the prominence of IMs that utilize images of originally violent or sensitive contexts may relate to existing research correlating violent media and desensitization. The use of these images often involves a disconnection from their original contexts in order to create a new and distinct— in many cases irrelevant— message and meaning. These IMs, in turn, exemplify the belittlement of distress depicted in such images—often for the sake of humor. This essay’s main goal is to propose a new theoretical lens from which to analyze the social and cultural influences on IMs. The greater purpose of this essay is not to devalue Internet memes nor to define them in narrow terms nor to claim there is any causal relationship between Internet memes and societal desensitization. Rather, I am proposing a new lens through which to further study Internet memes’ social effects on online users’ conceptions of violence and/or sensitive topics. -

Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and Its Multifarious Enemies

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/369 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Maxime Dafaure, « The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies », Angles [Online], 10 | 2020, Online since 01 April 2020, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/369 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies 1 The “Great Meme War:” the Alt- Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Memes and the metapolitics of the alt-right 1 The alt-right has been a major actor of the online culture wars of the past few years. Since it came to prominence during the 2014 Gamergate controversy,1 this loosely- defined, puzzling movement has achieved mainstream recognition and has been the subject of discussion by journalists and scholars alike. Although the movement is notoriously difficult to define, a few overarching themes can be delineated: unequivocal rejections of immigration and multiculturalism among most, if not all, alt- right subgroups; an intense criticism of feminism, in particular within the manosphere community, which itself is divided into several clans with different goals and subcultures (men’s rights activists, Men Going Their Own Way, pick-up artists, incels).2 Demographically speaking, an overwhelming majority of alt-righters are white heterosexual males, one of the major social categories who feel dispossessed and resentful, as pointed out as early as in the mid-20th century by Daniel Bell, and more recently by Michael Kimmel (Angry White Men 2013) and Dick Howard (Les Ombres de l’Amérique 2017). -

History of Rage Faces

History Of Rage Faces 1 / 6 History Of Rage Faces 2 / 6 3 / 6 A rage comic I made about a funeral. This is not a true story, and this is kind of a sensitive topic, so I apologize if any of you were offended. 1. history of rage faces How to fail at history, forever, Rage Comics, History Class, Social Studies ... Memes faces troll boss ideas for 2019 Rage Comics, Derp Comics, Funny Comics,.. Data on SMS Rage Faces and other apps by Robert Lemoine. ... SMS Rage Faces - 3000+ Faces and Memes. Robert Lemoine ... Category Ranking History.. All internet meme rage faces list in high quality! ... Don't Worry, Be Happy [High Quality] Smiley Faces ... history of rage faces history of rage faces, why rage face I’m back! On Ars Technica, Tom Connor does a great job producing a taxonomy and history of rage-faces, showing how they evolved from a set of .... History. The first rage comic was posted to the 4chan /b/random board in 2008. It was a simple 4-panel strip showing the author's anger about getting ... VirtualHostX 8.7.0 Crack Mac Osx 4 / 6 ConceptDraw Office 6.0.0.0 + Crack CalendarPro for Google 3.2 Owen or Blade I can see this as a story of sorts. Teh Meme Wiki. … Jan 29 ... Rage Faces Kissen und Face Meme online 5 / 6 kaufen. People write Me Gusta off as a .... Of these, rage comics are the easiest way to demonstrate Internet Ugly ... drawn faces, cut-and-paste characters that anyone can slap a story .. -

Internet Memes and Their Significance for Myth Studies

PALACKÝ UNIVERSITY, OLOMOUC FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND AMERICAN STUDIES INTERNET MEMES AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE FOR MYTH STUDIES DOCTORAL DISSERTATION Author: Mgr. Pavel Gončarov Supervisor: Prof. PhDr. Marcel Arbeit, Dr. 2016 UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA KATEDRA ANGLISTIKY A AMERIKANISTIKY INTERNETOVÉ MEMY A JEJICH VÝZNAM PRO VÝZKUM MYTOLOGIÍ DIZERTAČNÍ PRÁCE Autor práce: Mgr. Pavel Gončarov Vedoucí práce: Prof. PhDr. Marcel Arbeit, Dr. 2016 ANNOTATION Pavel Gončarov Department of English and American Studies, Faculty of Arts, Palacký University, Olomouc Title: Internet Memes and their Significance for Myth Studies Supervisor: Prof. PhDr. Marcel Arbeit, Dr. Language: English Character count: 347, 052 Number of appendices: 65 Entries in bibliography: 134 KEY WORDS myth, mythology, archaic revival, poetry, concrete poetry, semiotics, participatory media, digital culture, meme, memetics, internet memes, rage comics, Chinese rage comics, baozou manhua, baoman ABSTRACT This dissertation posits that the heart of myth rests with the novelizing and complexifying ritual of post-totemic sacrifice. As it makes an example of its delivery through poetry it tries to show the changing nature of poetry and art through history towards a designated act of whichever content. Transhumanism is seen as a tendency and so the dissertation imagines a poet whose practical exercise in the workings of typewriter produced concrete poetry are then tied to the coded ASCII table, emoticons and polychromatic glyphs which are subject to default visual modifications by manufacturers of technology. The dissertation then offers a view at memetic information transmission which is worked into a model that draws on Jacque Derrida’s différance. From a construction of a tree of hypothetical changes in the evolution of a state of culture of the primitive Waorani tribe, the dissertation moves to a logical exercise about hypernyms and hyponyms.