Tugboat, Volume 41 (2020), No. 3 263 How TEX Changed My Life Michael Barr Abstract I Describe the Complicated Process of Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ibm Selectric Repair Manual Download Ibm Selectric Repair Manual

Ibm Selectric Repair Manual Download Ibm Selectric Repair Manual Here is a vintage IBM early electric typewriter from the 50's, believe the model is 11C. It is an estate find in as found condition which is not working so selling AS IS for parts or for repair. Please see all pics for details, item is very heavy, Q's welcome. Parts Manual for the Imperial Electric Standard Typewriter. Published 1964. IBM Selectric Adjustment & Parts Manual Series 7xx, 8xx, 670x, 9xx. Published. IBM Selectric Maintenance Manual Maintenance manual (153 pages) Sears 153.33525 Owner's Manual Owner's manual (32 pages) Nakajima WPT- 160 Instruction Manual Instruction manual (40 pages) Canon AP 300 Instructions Manual Instructions manual (27 pages) Royal 79101t Classic Manual Typewriter (mint Green). 3.5 out of 5 stars 158. $149.99 Typewriter Ribbon Works with IBM Selectric III, Compatible, Replaces IBM.44 reviews of California Typewriter "If you ever need a typewriter repaired, this is the place to go. (And not because it is the only place to go.) Efficient and friendly staff. IBM "Selectric" Typewriter Service Manual: IBM "Selectric. Need a ribbon, a typewriter or don't want to DIY? Take a trip into the past in one of the handful of typewriter repair shops around the world. Ensconsed within each is a wizened wizard who can make your typewriter sing like it was new! Vintage IBM Selectric Typewriter Part Repair Manual And Large Lot Of Parts Rare. Current Price: USD 299.00. View Auction. Typewriters > Bend,OR,USA Enjoy and visit my blog for truly free, because there is no ad campaign, moreover you can choose the format Ibm Selectric Ii Typewriter Manual Online do you want as PDF, Kindle, ePub, iPhone and Mobi, etc Ibm Selectric Ii Typewriter Manual PDF Kindle Ibm Selectric Ii Typewriter Manual available in formats PDF, Kindle, ePub, iTunes and Mobi also.I have a Selectric II also, in about the same condition, and managed to get a xerox of the service manual at one point, to help keep it running. -

Oral History of George E. Comstock

• Computer • History Museum Oral History of George E. Comstock Interviewed by: Gardner Hendrie Recorded: August 13, 2003 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X2727.2004 © 2004 Computer History Museum Oral History of George E. Comstock Gardner Hendrie: George I'd probably like to start really far back, where you were born and grew up. George Comstock: Well gosh, if you were to ask my wife that question she might answer that I never have grown up <laughs>. But taking it in a more literal sense, I was born in Canandaigua, New York, but only lived there for a year, so I have relatively little memory of it. My first memories really are of Worcester, Massachusetts where my parents moved when I was five years old. So I grew up in Worcester. And I was about nine years old when I got acquainted with the older brother of one of my playmates, Al Howell, they lived across the street from where I lived and he at the age of 15 was an avid model airplane builder. So he got me involved at the age of nine in learning how to build model airplanes, and that became quite a career for me during grammar school and high school. I must have built several hundred models before I was done including maybe a hundred gas models and lost a few in cumulus clouds, you know <laughs>. So that got me started on an engineering career, really, that's why I mention it, 'cause he went on to go to school at Worcester Tech (WPI), became a mechanical engineer and young George figured there couldn't be anything better to do than what Al Howell did, so I went to Worcester Tech and became a mechanical engineer, I graduated in 1945with a BS in mechanical engineering. -

Masked Iranians Protest Shah by ANDY CLINE and KATE TYLER Return, Said a Demonstrator

Vol. 102, No. 20 UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE, NEWARK, DEL. On the Masked Iranians Protest Shah By ANDY CLINE and KATE TYLER return, said a demonstrator. \ Inside With chants of "Down with university community's at The Shah's police, SA VAK, the Shah" and "U.S. ad tention the true nature of allegedly keep tabs on Ira visors, CIA agents out of repression in Iran; to make nian students studying Iran," seventeen masked Ira people more sensitive to a abroad. nian students marched across situation that on the surface The protestors marched to The "Real World" campus on Friday to protest seems beyond the scope of the International Center, set the policies of Shah Moham students day to day life," said. up a picket line, and con explained med Reza Pahlavi of Iran. student supporter Steven tinued chanting. In their Business Exec. visits On the steps of Hullihen Krevisky. chants they compared the Hall, one demonstrator read The letter alleges "over- struggle in Iran to that in campus ................ p. 3 an open letter from the Ira 20,000 innocent men, women Vietnam. They called for the nian Student Association and children have been continued "solidarity bet ( ISA) outlining their massacred under the direct ween Iranian and American grievances with the Shah's orders of the Shah during the peoples." It Hasn't government. past eight months," in order By noon, the demonstration A copy of the letter was to suppress political dissent. moved back across campus Been Easy taken to university President The demonstrators wore toward the Student Center. E.A. -

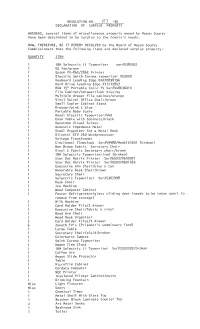

Declaration of Surplus Property Page 2

RESOLUTION NO. -95 DECLARATION OF SUR=P;-;LU-:-:::S:---;P=R=OP-ERTY WHEREAS, several items of miscellaneous property owned by Mason County have been determined to be surplus to the County 1 s needs: NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT HEREBY RESOLVED by the Board of Mason County Commissioners that the following items are declared surplus property: QUANTITY ITEM l IBM Selectric I I Typewriter ser#5385921 1 GE fan/green l Epson FX-86E/286E Printer l Electric Smith Corona typewriter XE5000 l Keyboard Leading Edge DKA70898796 l Hard Drive Leading Edge #71212847 l RCW 15 11 Portable Color TV Ser#448636010 l File Cabinet/4drawer/lock missing 1 Multiple drawer file cabinet/orange 1 Vinyl Swivel Office Chair/brown 1 Small Copier Cabinet Stand 1 Dresser/pink & blue 1 Portable Baby Scale 1 Royal Electric Typewriter/440 1 Exam Table with Cabinets/black l Keystone Visual Survey l Acoustic Impedance Meter l Steel Organizer for a Metal Desk l Olivetti ETV 240 Wordprocessor 1 Voltage Transformer 1 Cincinnati Timeclock Ser#499BB/Mode1#3501 (broken) l Hon Brown Fabric Secretary Chair l Vinyl & Fabric Secretary chair/brown 1 IBM Selectric Typewriter/red (broken) l Star Dot Matrix Printer Ser#650370600971 1 Star Dot Matrix Printer Ser#050370601463 1 Executive Arm Chair/blue & tan 1 Honorable Desk Chair/brown 1 Secretary Chair l Selectric Typewriter Ser#5367998 l Desk Chair l Ice Machine l Wood Computer Cabinet 1 Foster Refrigerator/glass sliding door (needs to be taken apart to remove from storage) Mi l k Mach i n e Card Holder File/2 drawer Executive Chair/fabric & -

History of Telegraphy from the Teletype Museum

History of Telegraphy from the Teletype Museum Ransom D. Slayton, Consultant 1983 (Document Notes) The Teletype Museum display was set up several years ago by Charley Hill and Ken Lovitt, and served for some time as a magnet attraction for visitors to the Teletype plant. Later, due to the compelling demand for more office space as the company expanded, the Museum was dismantled and the equipment on display sent to storage. A record set of slide pictures was made just before this occurred, and this program is a "walk through" of the Museum as it appeared in its better days. join us for a trip back into the History of the Telegraph Art as illustrated by the machines developed by the in- ventors who contributed so much to communications progress in the old days. 1. Our greeting is an appropriate "START HERE" with the beginning of a series of numbered captions covering various steps in THE HISTORY OF TELE- GRAPHY. Early forms, before 1820 include semaphores and electro-chemical signaling methods, but historical records tell of signal fires, smoke sig- nals, and even an "encoded torch" system in which the lighted torches were placed in numbered notches on top of high walls, the combinations of tor- ches thus indicating the letters, numbers or pre-selected words being transmitted. It was great for both day and night, but look out for rain or fog!! 2. Most people think of telegraphy in terms of the old Morse code Key and Sounder, so this was the first display. The Sounder had a reflector box behind it, amplifying the clicks of the "Dots and Dashes" to the operator's ears. -

The Interface IBM and the Transformation of Corporate Design 1945-1976

The Interface IBM and the Transformation of Corporate Design 1945-1976 John Harwood A Quadrant Book University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London QUADRANT On the way from mythology to logistics, thought has lost the element of self-reflection, Quadrant, a joint initiative of the University of Published by the Minnesota Press and the Institute for Advanced University of Minnesota Press and today machinery disables men even as it nurtures them. Study at the University of Minnesota, provides 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 support for interdisciplinary scholarship within Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 a new collaborative model of research and http://www.upress.umn.edu Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer publication. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dialectic of Enlightenment Sponsored by the Quadrant Design, Architecture, Harwood, John and Culture group (advisory board: John Archer, The interface :IBM and the transformation of Ritu Bhatt, Marilyn Delong, Kate Solomonson) and corporate design, 1945-1976 I John Harwood. the University of Minnesota's College of Design. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. Quadrant is generously funded by the Andrew W. ISBN 978-0-8166-7039-0 (he : alk. paper) Mellon Foundation. ISBN 978-0-8166-7452-7 (pb : alk. paper) http://quadrant.umn.edu 1 . International Business Machines Corporation History. 2. Corporations-United States-History. This book is supported by a grant from the 3. Industrial design. 4. Modern movement Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the (Architecture)-United States. 5. Noyes, Eliot. Fine Arts. 6. Rand, Paul, 1914-1996. I. Title. HD9696.2.U6412547 2011 Every effort was made to obtain permission to 338. -

California State University, Northridge the Impact Of

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THE IMPACT OF THE FUTURE ON THE NEWSPAPER ·' A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Mass Communication by Herbert Paul Ford ,/ January, 1975 The thes#of Herb..eft} Paul Ford is approved: California State University, Northridge December, 1974 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Several persons are due special thanks for the part they have played in the inspiration and execution of this thesis. Dr. DeWayne Johnson, professor of journalism at California State University, Northridge, stimulated my thinking over a period of months as the original idea for the thesis was developing. Throughout prepa ration of the manuscript he gave consistently helpful guidance and en couragement. Initial steps in the thesis preparation were taken under the di rection of Dr. Joseph N. Webb of the California State University, Northridge, journalism faculty. His presentation of diverse, new re search methods and his concern for the subject is much appreciated. Gratitude is also due the World Future Society, Media General, Inc., and the faculty and staff of Pacific Union College for materials and other help given as work on the thesis went forward. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii Chapter I. FUTURE'S WORLD ..... 1 II. THE FUTURE AND ITS STUDY. 12 III. IMPACTUS ... 33 IV. FUTURE FREE?. 60 V. THROUGH THE STAR GATE • • • 76 BIBLIOGRAPHY .• . 94 ( iv ABSTRACT THE IMPACT OF THE FUTURE ON THE NEWSPAPER by Herbert Paul Ford Master of Arts in Mass Communications December, 1974 In terms of itself print journalism has devoted most of its atten tion to the past and the present. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. The Everyday Always Happens to Someone Else: An attempt at practising an endotic-based art Gerry Smith Ph.D University of Edinburgh 2016 I declare that: This thesis was composed by me and is my own work It has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification Gerry Smith Edinburgh College of Art University of Edinburgh 2016 The Everyday Always Happens to Someone Else: An attempt at practising an endotic-based art This thesis is an account of my three sites-in-endotics, each project resulting in a participatory artwork: Thaw (2012), Northern Venetians (2013) and The Recollective (2015). I base these projects upon the writings of Georges Perec (1936-82). Perec saw endotics as a form of quotidian studies characterised by an internal perspective: everyday situations should be described from the vantage point of those already immersed in them, not from the position of an outsider. -

Holmes,J.Pdf (8.528Mb)

\ FORMATTING VARIABLES AND TYPEFACE VARIATIONS OF DOT-MATRIX PRINT AND THEIR EFFECT ON / READING COMPREHENSION AND READING SPEED by James A. Holmes, Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION in Vocational and Technical Education M.’ E. Sanders, Co-Chairman TTA Binge E. H. Sewell March, 1986 Blacksburg, Virginia FORMATTING VARIABLES AND TYFEFACE VARIATIONS OF DOT-MATRIX FRINT AND THEIR EFFECT ON READING COMPREHENSION AND READING SFEED by James A. Holmes Committee Co-Chairmen: E. Allen Bame and Mark E. Sanders Vocational—-Technical Education CABSTRACT) The purpose of this study was to determine whether three typeface variations of dot matri: print Csingle density, dual density, and PFhotocopied dot matrix type] and two formatting Variations (fully justified and left justifiedi had any effect on the reading rates or reading comprehension of college students when compared toa the same typewritten material. A pretest/posttest design with experimental and control groups utilized the Cloze Reading Test and the Nelson Denny Reading Test to measure reading comprehension and reading rates respectively to college students [N= 240]. Subjects were randomly assigned to the groups to test the effects of the Six treatment levels and two control groups of the independent variables [typefaces and type formatting] on the dependent variables Creading comprehension and reading rated. Four test sessions were used to collect the data and answer the research question: Do either of the three typeface variations of dot matrix print ar the two formatting variables have any effect on reading comprehension or reading rates of the subjects when compared to typewriter type? A factorial analysis of covariance [Ep. -

INIS Pioneering Information Management: the Early Days of Computerized Acquisition, Processing and Storage of Data at the IAEA

Nuclear Information Newsletter www.iaea.org/inis ISSN 2410-4940 (online) No. 17, October 2015 45th INIS Anniversary Newsletter INIS Pioneering Information Management: The early days of computerized acquisition, processing and storage of data at the IAEA In his third Law, British author, Sir Arthur C. Clarke, states that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. When a technology becomes estranged due to the inevitable process of obsolescence, it becomes alien to the untrained eye, unfamiliar and obscure – elements that possibly add up on the original mystique of early computers. In this article we will take a look at a number of early information technologies, some gone, some forgotten, some still Riccardo Rubini has been alive-and-well, to unveil the magic that has greatly contributed to INIS, working in the field of throughout its 45 year journey in the realms of nuclear culture for Information Technology for over twelve years, both in the private peaceful uses. and public sector. He currently serves as Information Architect in the Software Development and Support Group (SDSG) within the NIS Section. First computer of the IAEA FIG. 1. An IBM System/360 together with peripherals; the console is visible in the forefront. In the beginning, there was the computer: heralded as a “Giant Brain” by the press, the first computers of the 1940s, such as the ENIAC, were a jumble of vacuum tubes, crystal diodes, relays, resistors and capacitors, over a million of hand-soldered joints, spreading over an entire building: all with the same computing power as that of a modern pocket calculator. -

Jewelry Appraiser a Publication of the National Association of Jewelry Appraisers Serving the Professional Jewelry Appraiser with Pride©

The Jewelry Appraiser a publication of the national association of jewelry appraisers Serving the Professional Jewelry Appraiser With Pride© April/May/June 2019 Vol. XIII, No. 2 52nd ACE© It Mid Year Education Conference Dallas, TX August 3-6, 2019 Heritage Auctions, Dallas Design District Showroom, 1518 Slocum Street, Dallas, TX 75207 214-409-1444 People in Dallas pepper their sentences with “sir” and “ma’am” and say “Howdy” like it’s an obligatory greeting. You won’t be able to resist that Texan drawl and soon enough you’ll be “ya’ll”-ing with the rest of them. Texans are a friendly bunch, and they love their cowboy hats and boots. Fun fact: Deep Ellum is well known for its diverse arts and entertainment culture, probably because it has more bars and nightclubs than any other district in the city. In the 1920s, it was a haven for jazz and blues artists such as Blind Lemon Jefferson, Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter and Bessie Smith. The name is a derivative of what locals once called “deep Elm Street.” Dallas is known for its barbecue, authentic Mexican, and Tex-Mex cuisine. Famous products of the Dallas culinary scene include the frozen margarita! - Rakel Hall GREAT BIG TEXAS SIZE THANK YOU! A huge debt of gratitude to Jill Burgum and the entire Heritage Auction team for hosting the NAJA conference. Heritage Auction is also the major sponsor with such delights as a Heritage Texas style goody bag, a champagne reception, Texas bar-be-que lunch and, wait for it, a mock auction with real prizes and real goodies to successfully bid on! All proceeds are designated to the Howard Rubin Education Foundation. -

Identifying the Physical Source of the Bush Memos

WORK IN PROGRESS Initially, this was just a small work examining just a single component of the Bush Memos. Because of recent interest in the work, however, I have been asked to push the project thorough to completion – seeing if this information might be useful for tracking down the origin of the Bush memos. That said, this report will continuously develop until the project is completed. The next step will be a statistical evaluation of commonly and uncommonly used characters. David Hailey REPORT Toward Identifying the Font Families in the Bush Memos David E Hailey, Jr., Principal Investigator Associate Professor of Technical Communications Utah State University ABSTRACT The following evidence from a forensic examination of the Bush memos indicates that they were typed on a typewriter: 1. The specific font used is from a typewriter family in common use since (circa) 1905. 2. The characters “e,” “t,” “s,” and “a” show indications of physical damage and/or wear. 3. The characters that are seldom used (e.g., numbers) show few indicators of damage or wear. 4. The consistent quality of individual character types throughout the memos seem to be inconsistent with a theory their defects are caused by random artifacts from copying, but may be consistent with worn platen and variations in paper quality. 5. Overlapping characters occasionally indicate paper deformation consistent with hammered impressions. 6. Critical indicators of digital production are missing. Implications are that there is nothing in this evidence that would indicate the memos are inauthentic. Furthermore, from the point of view of the physical evidence in the documents (excluding any rhetorical evidence or external evidence, which is not examined in this study) I believe that no amount of additional research on the part of CBS would have lead them to exclude the documents from their 60 Minutes report.