Close Reading and Douglas Sirk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Melodrama, Sickness, and Paranoia: Todd Haynes and the Womanâ•Žs

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley ScholarWorks @ UTRGV Literatures and Cultural Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations College of Liberal Arts Winter 2016 Melodrama, Sickness, and Paranoia: Todd Haynes and the Woman’s Film Linda Belau The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Ed Cameron The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/lcs_fac Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Belau, L., & Cameron, E. (2016). Melodrama, Sickness, and Paranoia: Todd Haynes and the Woman’s Film. Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal 46(2), 35-45. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/643290. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts at ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. It has been accepted for inclusion in Literatures and Cultural Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Film & History 46.2 (Winter 2016) MELODRAMA, SICKNESS, AND PARANOIA: has so much appeal precisely for its liberation from yesterday’s film culture? TODD HAYNES AND THE WOMAN’S FILM According to Mary Ann Doane, the classical woman’s film is beset culturally by Linda Belau the problem of a woman’s desire (a subject University of Texas – Pan American famously explored by writers like Simone de Beauvoir, Julia Kristeva, Helene Cixous, and Ed Cameron Laura Mulvey). What can a woman want? University of Texas – Pan American Doane explains that filmic conventions of the period, not least the Hays Code restrictions, prevented “such an exploration,” leaving repressed material to ilmmaker Todd Haynes has claimed emerge only indirectly, in “stress points” that his films do not create cultural and “perturbations” within the film’s mise artifacts so much as appropriate and F en scène (Doane 1987, 13). -

Copyrighted Material

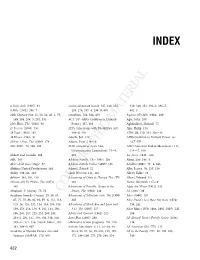

9781405170550_6_ind.qxd 16/10/2008 17:02 Page 432 INDEX 4 Little Girls (1997) 93 action-adventure movie 147, 149, 254, 339, 348, 352, 392–3, 396–7, 8 Mile (2002) 396–7 259, 276, 287–8, 298–9, 410 402–3 20th Century-Fox 21, 30, 34, 40–2, 73, actualities 106, 364, 410 Against All Odds (1984) 289 149, 184, 204–5, 281, 335 ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Agar, John 268 25th Hour, The (2002) 98 Power) 337, 410 Aghdashloo, Shohreh 75 27 Dresses (2008) 353 ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) Ahn, Philip 130 28 Days (2000) 293 398–9, 410 AIDS 99, 329, 334, 336–40 48 Hours (1982) 91 Adachi, Jeff 139 AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power see 100-to-1 Shot, The (1906) 174 Adams, Evan 118–19 ACT-UP 300 (2007) 74, 298, 300 ADC (American-Arab Anti- AIM (American Indian Movement) 111, Discrimination Committee) 73–4, 116–17, 410 Abbott and Costello 268 410 Air Force (1943) 268 ABC 340 Addams Family, The (1991) 156 Akins, Zoe 388–9 Abie’s Irish Rose (stage) 57 Addams Family Values (1993) 156 Aladdin (1992) 73–4, 246 Abilities United Productions 384 Adiarte, Patrick 72 Alba, Jessica 76, 155, 159 ability 359–84, 410 adult Western 111, 410 Albert, Eddie 72 ableism 361, 381, 410 Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet, The (TV) Albert, Edward 375 Abominable Dr Phibes, The (1971) 284 Alexie, Sherman 117–18 365 Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Algie, the Miner (1912) 312 Abraham, F. Murray 75, 76 COPYRIGHTEDDesert, The (1994) 348 MATERIALAli (2001) 96 Academy Awards (Oscars) 29, 58, 63, Adventures of Sebastian Cole, The (1998) Alice (1990) 130 67, 72, 75, 83, 92, 93, -

Homosexuality and the 1960S Crisis of Masculinity in the Gay Deceivers

Why Don’t You Take Your Dress Off and Fight Like a Man? WHY DON’T YOU TAKE YOUR DRESS OFF AND FIGHT LIKE A MAN?: HOMOSEXUALITY AND THE 1960S CRISIS OF MASCULINITY IN THE GAY DECEIVERS BRIAN W OODMAN University of Kansas During the 1960s, it seemed like everything changed. The youth culture shook up the status quo of the United States with its inves- titure in the counterculture, drugs, and rock and roll. Students turned their universities upside-down with the spirit of protest as they fought for free speech and equality and against the Vietnam War. Many previously ignored groups, such as African Americans and women, stood up for their rights. Radical politics began to challenge the primacy of the staid old national parties. “The Kids” were now in charge, and the traditional social and cultural roles were being challenged. Everything old was old-fashioned, and the future had never seemed more unknown. Nowhere was this spirit of youthful metamorphosis more ob- vious than in the transformation of views of sexuality. In the 1960s sexuality was finally removed from its private closet and cele- brated in the public sphere. Much of the nation latched onto this new feeling of openness and freedom toward sexual expression. In the era of “free love” that characterized the latter part of the decade, many individuals began to explore their own sexuality as well as what it meant to be a traditional man or woman. It is from this historical context that the Hollywood B-movie The Gay Deceivers (1969) emerged. This small exploitation film, directed by Bruce Kessler and written by Jerome Wish, capitalizes on the new view of sexuality in the 1960s with its novel (at least for the times) comedic exploration of homosexu- ality. -

Elizabeth Taylor: Screen Goddess

PRESS RELEASE: June 2011 11/5 Elizabeth Taylor: Screen Goddess BFI Southbank Salutes the Hollywood Legend On 23 March 2011 Hollywood – and the world – lost a living legend when Dame Elizabeth Taylor died. As a tribute to her BFI Southbank presents a season of some of her finest films, this August, including Giant (1956), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966). Throughout her career she won two Academy Awards and was nominated for a further three, and, beauty aside, was known for her humanitarian work and fearless social activism. Elizabeth Taylor was born in Hampstead, London, on 27 February 1932 to affluent American parents, and moved to the US just months before the outbreak of WWII. Retired stage actress Sara Southern doggedly promoted her daughter’s career as a child star, culminating in the hit National Velvet (1944), when she was just 12, and was instrumental in the reluctant teenager’s successful transition to adult roles. Her first big success in an adult role came with Vincente Minnelli’s Father of the Bride (1950), before her burgeoning sexuality was recognised and she was cast as a wealthy young seductress in A Place in the Sun (1951) – her first on-screen partnership with Montgomery Clift (a friend to whom Taylor remained fiercely loyal until Clift’s death in 1966). Together they were hailed as the most beautiful movie couple in Hollywood history. The oil-epic Giant (1956) came next, followed by Raintree County (1958), which earned the actress her first Oscar nomination and saw Taylor reunited with Clift, though it was during the filming that he was in the infamous car crash that would leave him physically and mentally scarred. -

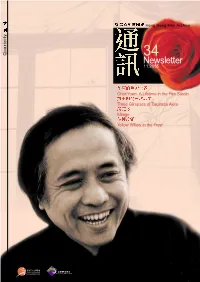

Newsletter 34

Hong Kong Film Archive Quarterly 34 Newsletter 11.2005 Chor Yuen: A Lifetime in the Film Studio Three Glimpses of Takarada Akira Mirage Yellow Willow in the Frost 17 Editorial@ChatRoom English edition of Monographs of HK Film Veterans (3): Chor Yuen is to be released in April 2006. www.filmarchive.gov.hk Hong Kong Film Archive Head Angela Tong Section Heads Venue Mgt Rebecca Lam Takarada Akira danced his way in October. In November, Anna May Wong and Jean Cocteau make their entrance. IT Systems Lawrence Hui And comes January, films ranging from Cheung Wood-yau to Stephen Chow will be revisited in a retrospective on Acquisition Mable Ho Chor Yuen. Conservation Edward Tse Reviewing Chor Yuen’s films in recent months, certain scenes struck me as being uncannily familiar. I realised I Resource Centre Chau Yu-ching must have seen the film as a child though I couldn’t have known then that the director was Chor Yuen. But Research Wong Ain-ling coming to think of it, he did leave his mark on silver screen and TV alike for half a century. Tracing his work brings Editorial Kwok Ching-ling Programming Sam Ho to light how Cantonese and Mandarin cinema evolved into Hong Kong cinema. Today, in the light of the Chinese Winnie Fu film market and the need for Hong Kong cinema to reorient itself, his story about flowers sprouting from the borrowed seeds of Cantonese opera takes on special meaning. Newsletter I saw Anna May Wong for the first time during the test screening. The young artist was heart-rendering. -

Pdf El Trascendentalismo En El Cine De Douglas Sirk / Emeterio Díez

EL TRASCENDENTALISMO EN EL CINE DE DOUGLAS SIRK Emeterio DÍEZ PUERTAS Universidad Camilo José Cela [email protected] Resumen: El artículo estudia la presencia del trascendentalismo en las pelí- culas que Douglas Sirk rueda para los estudios Universal Internacional Pic- tures entre 1950 y 1959. Dicha presencia se detecta en una serie de motivos temáticos y en una carga simbólica acorde con una corriente literaria y filo- sófica basada en la intuición, el sentimiento y el espíritu. Abstract: The article studies the presence of the transcendentalist in the movies that Douglas Sirk films between 1950 and 1959 for Universal Inter- national Pictures. This presence is detected in topics and symbols. Sirk uni- tes this way to a literary and philosophical movement based on the intuition, the feeling and the spirit. Palabras clave: Douglas Sirk. Trascendentalismo. Leitmotiv. Cine. Key words: Douglas Sirk. Trascendentalist. Leitmotiv. Cinema. © UNED. Revista Signa 16 (2007), págs. 345-363 345 EMETERIO DÍEZ PUERTAS Hacia 1830 surge en la costa Este de Estados Unidos un movimiento li- terario y filosófico conocido como trascendentalismo. Se trata de una co- rriente intelectual que rechaza tanto el racionalismo de la Ilustración como el puritanismo conservador y el unitarismo cristiano. Sus ideas nacen bajo el in- flujo del romanticismo inglés y alemán, en especial, de las lecturas de Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge y Thomas Carlyle. Los principales teóricos del movimiento se agrupan en torno a la ciudad de Concord, en Massachusetts, uno de los seis estados que forman Nueva Inglaterra. Con apenas cinco mil habitantes, esta pequeña localidad se convierte en el centro de toda una escuela de pensamiento. -

Bamcinématek Presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 Days of 40 Genre-Busting Films, Aug 5—24

BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 days of 40 genre-busting films, Aug 5—24 “One of the undisputed masters of modern genre cinema.” —Tom Huddleston, Time Out London Dante to appear in person at select screenings Aug 5—Aug 7 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Jul 18, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, August 5, through Wednesday, August 24, BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, a sprawling collection of Dante’s essential film and television work along with offbeat favorites hand-picked by the director. Additionally, Dante will appear in person at the August 5 screening of Gremlins (1984), August 6 screening of Matinee (1990), and the August 7 free screening of rarely seen The Movie Orgy (1968). Original and unapologetically entertaining, the films of Joe Dante both celebrate and skewer American culture. Dante got his start working for Roger Corman, and an appreciation for unpretentious, low-budget ingenuity runs throughout his films. The series kicks off with the essential box-office sensation Gremlins (1984—Aug 5, 8 & 20), with Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates. Billy (Galligan) finds out the hard way what happens when you feed a Mogwai after midnight and mini terrors take over his all-American town. Continuing the necessary viewing is the “uninhibited and uproarious monster bash,” (Michael Sragow, New Yorker) Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990—Aug 6 & 20). Dante’s sequel to his commercial hit plays like a spoof of the original, with occasional bursts of horror and celebrity cameos. In The Howling (1981), a news anchor finds herself the target of a shape-shifting serial killer in Dante’s take on the werewolf genre. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series HUM2014-0814

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series HUM2014-0814 Iconic Bodies/Exotic Pinups: The Mystique of Rita Hayworth and Zarah Leander Galina Bakhtiarova Associate Professor Western Connecticut State University USA 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN 2241-2891 22/1/2014 2 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. The papers published in the series have not been refereed and are published as they were submitted by the author. The series serves two purposes. First, we want to disseminate the information as fast as possible. Second, by doing so, the authors can receive comments useful to revise their papers before they are considered for publication in one of ATINER's books, following our standard procedures of a blind review. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research 3 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 This paper should be cited as follows: Bakhtiarova, G. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Feb. Date for CIP Vote

FLORIDA ATLANTIC STATE UNIVERSITY OPENS IN BOCA RATON IN 1964 Largest Circulation Boca Raton News Bldg. Of Any Newspaper 34 IE. Second St, In Boca Raton Area BOCA RATON NEWS Phone 395-5121 VOL. 7 NO. 44 Boca Raton, Palm Beach County, Florida, Thursday, September 27, 1962 16 Pages PRICE TEN CENTS Feb. Date for CIP Vote Commission Will Study Dickinson Speaks Here-Sees FAU Organization of-Ballot A referendum on Boca In the past the City Becoming 'Cambridge of America' Raton's proposed Capital Commissioners have indi- Former State Senator He said the Council is Improvement Program will cated a desire to provide Fred O. "Bud" Dickinson, now working on the three- be held next February. as many categories as chairman of the Florida acre Florida exhibit to be The City Commission, possible on the ballot. In Council of 100, was guest set up at the New York at its regular . meeting this way, voters would be speaker at the Rotary Club World's Fair in a choice Tuesday, set the second able to express different yesterday. location. He told how tele- Tuesday in February as opinions on many of the vision shows such as the date for a referendum individual projects pro- "The glory of Florida is Arthur Godfrey's were in- on the program. The date posed. State laws require not what happened yester- duced to come to Florida coincides with the date of certain divisions on the day, but what is happening and how the show "Today" the primary election for ballot, today and the even great- is televised from the RCA City Commission candi- The City's Board of er and brighter happenings Building in New York dates. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism.