Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

É M I L I E Livret D’Amin Maalouf

KAIJA SAARIAHO É M I L I E Livret d’Amin Maalouf Opéra en neuf scènes 2010 OPERA de LYON LIVRET 5 Fiche technique 7 L’argument 10 Le(s) personnage(s) 16 ÉMILIE CAHIER de LECTURES Voltaire 37 Épitaphe pour Émilie du Châtelet Kaija Saariaho 38 Émilie pour Karita Émilie du Châtelet 43 Les grandes machines du bonheur Serge Lamothe 48 Feu, lumière, couleurs, les intuitions d’Émilie 51 Les derniers mois de la dame des Lumières Émilie du Châtelet 59 Mon malheureux secret 60 Je suis bien indignée de vous aimer autant 61 Voltaire Correspondance CARNET de NOTES Kaija Saariaho 66 Repères biographiques 69 Discographie, Vidéographie, Internet Madame du Châtelet 72 Notice bibliographique Amin Maalouf 73 Repères biographiques 74 Notice bibliographique Illustration. Planches de l’Encyclopédie de Diderot et D’Alembert, Paris, 1751-1772 Gravures du Recueil de planches sur les sciences, les arts libéraux & les arts méchaniques, volumes V & XII LIVRET Le livret est écrit par l’écrivain et romancier Amin Maalouf. Il s’inspire de la vie et des travaux d’Émilie du Châtelet. Émilie est le quatrième livret composé par Amin Maalouf pour et avec Kaija Saariaho, après L’Amour de loin, Adriana Mater 5 et La Passion de Simone. PARTITION Kaija Saariaho commence l’écriture de la partition orches- trale en septembre 2008 et la termine le 19 mai 2009. L’œuvre a été composée à Paris et à Courtempierre (Loiret). Émilie est une commande de l’Opéra national de Lyon, du Barbican Centre de Londres et de la Fondation Gulbenkian. Elle est publiée par Chester Music Ltd. -

Circle Map Program of Contemporary Classical Works by Kaija Saariaho to Feature New York Premieres Performed by the New York Philharmonic

Circle Map Program of Contemporary Classical Works by Kaija Saariaho to Feature New York Premieres Performed by the New York Philharmonic Site-Specific Realization by Armory Artistic Director Pierre Audi Conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen Two Performances Only - October 13 and 14, 2016 New York, NY — August 16, 2016 — Park Avenue Armory will present Circle Map, two evenings of immersive spatial works by internationally acclaimed Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho performed by the New York Philharmonic under the baton of its Marie-Josée Kravis Composer-in-Residence Esa-Pekka Salonen on October 13 and 14, 2016. Conceived by Pierre Audi to take full advantage of the Wade Thompson Drill Hall, the engagement marks the orchestra’s first performance at the Armory since 2012’s Philharmonic 360, the acclaimed spatial music program co-produced by the Armory and Philharmonic. A program of four ambitious works that require a massive, open space for their full realization, Circle Map will utilize the vast drill hall in an immersive presentation that continually shifts the relationship between performers and audience. The staging will place the orchestra at the center of the hall, with audience members in a half-round seating arrangement and performances taking place throughout. Longtime Saariaho collaborator Jean-Baptiste Barrière will translate the composer’s soundscapes into projections that include interpretations of literary and visual artworks from which inspiration for specific compositions are drawn. “Our drill hall is an ideal setting and partner for realizing spatial compositions, providing tremendous freedom for composers and performers,” said Rebecca Robertson, President and Executive Producer of Park Avenue Armory. -

La Passion De Simone

LA PASSION DE SIMONE SYDNEY CHAMBER OPERA IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE SONG COMPANY l AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE Photo: Samuel Hodge Photo: ABOUT THE SHOW LA PASSION Passion and philosophy collide in a glimmering ascent DE SIMONE to enlightenment. Simone Weil bestrode the 20th century as a figure of SYDNEY CHAMBER OPERA IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE SONG COMPANY l AUSTRALIA impossible grace. Acclaimed Finnish composer Kaija AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE Saariaho tells her story through music in this deeply CARRIAGEWORKS spiritual work, never before seen in Australia. 9–11 JANUARY Saariaho’s score is luminous and coruscating, blending 75 MINS a single incredible soloist with the voices of The Song Company and 19 virtuoso instrumentalists. Star soprano Music Kaija Saariaho Jane Sheldon (The Howling Girls, An Index of Metals) leads Text Amin Maalouf the audience through Weil’s extraordinary life, from her Jack Symonds rejection of labour during World War II to her exile into Conductor DIRECTOR’S NOTE Kaija Saariaho is a prominent member of a group of Director Imara Savage self-imposed starvation in protest of the Holocaust’s “All the natural movements of the soul are controlled Finnish composers and performers who are now, in Set & Costume Designer Elizabeth Gadsby atrocities. Director Imara Savage and designer Elizabeth by laws analogous to those of physical gravity. Grace mid-career, making a worldwide impact. She studied Lighting Designer Alexander Berlage Gadsby, the creative team behind the acclaimed Fly Away is the only exception. Grace fills empty spaces, but it composition in Helsinki, Freiburg and Paris, where Video Artist Mike Daly Peter, return to Sydney Chamber Opera for this shimmering can only enter where there is a void to receive it, and it she has lived since 1982. -

Confluencias Entre Escena Y Ópera Contemporáneas Andrea Tortosa Baquero

Confluencias entre escena y ópera contemporáneas Las colaboraciones entre Kaija Saariaho y Peter Sellars en el género operístico de 1998 a 2006 Andrea Tortosa Baquero Espacio Sonoro. Nº 40. Septiembre 2016 Confluencias entre escena y ópera contemporáneas Andrea Tortosa Baquero El siguiente artículo se basa en el trabajo de fin de grado Nuevos Caminos para la Escena Musical. Las Colaboraciones entre Kaija Saariaho y Peter Sellars en el Género Operístico de 1998 a 2006, defendido en el Departament d’Art i Musicologia (Grado en Musicología) de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona en febrero de 2016. INTRODUCCIÓN Adentrarse en el panorama artístico de las últimas décadas no es una cuestión sencilla. Escuelas y artistas han roto con los modelos preestablecidos creándose una aceleración de la dinámica de cambios estéticos, socioculturales y de técnicas musicales. Una de las figuras más distinguidas en el mundo de la composición en la actualidad es la finlandesa Kaija Saariaho (1952), que desde finales de los años noventa decidió adentrarse en el género operístico. Aunque en un principio Saariaho se mostrara reacia a la idea de empezar a trabajar en el mundo de la ópera, llegó un momento en el que necesitó de este género para seguir expresando todo aquello que quería. Amor y muerte, seguramente considerados los temas más utilizados en la tradición operística, le fascinaban, queriendo aproximarse a ellos a través de sus composiciones. Las composiciones operísticas pueden también ser entendidas como una continuación lógica de su crecimiento como compositora debido a que la dimensión visual y el uso de textos literarios como fuente de inspiración han estado siempre presentes en su proceso compositivo. -

Figura Kenozy W Literaturze I Muzyce. Przypadek Oratorium La Passion De Simone Kaiji Saariaho

#0# Rocznik Komparatystyczny – Comparative Yearbook 8 (2017) DOI: 10.18276/rk.2017.8-11 Katarzyna Kucia Uniwersytet Jagielloński Figura kenozy w literaturze i muzyce. Przypadek oratorium La Passion de Simone Kaiji Saariaho Libretto, oprócz tego, że oznacza tworzywo słowne przedstawienia muzycznego, jakim jest opera lub oratorium, etymologicznie oznacza po prostu książeczkę. Utwór La Passion de Simone, choć opowiada o niespokojnym życiu francuskiej filozofki Simone Weil oraz jej wielkich ideach, powstał głównie na podstawie książki o niewielkiej objętości, zatytułowanej La pesanteur et la grâce (Weil, 1947)1. Publikacja ta stanowi wybór rozproszonych myśli Weil, dokonany przez Gustave’a Thibona w cztery lata po śmierci autorki – esencję zapisywanych przez 10 lat na tysiącach stron notatek (Weil, 1991). Zbiór ten jest pierwszą opubli- kowaną książką francuskiej filozofki i często pierwszą lekturą zainteresowanych jej myślą. Tę właśnie książeczkę, jedyną spośród innych dzieł myślicielki, prze- tłumaczoną w 1957 roku na język fiński (Weil, 1957), zabrała ze sobą w podróż w 1981 roku na zagraniczne studia muzyczne do Fryburga Bryzgowijskiego fińska kompozytorka Kaija Saariaho, na wiele lat przed powstaniem La Passion de Simone. Młoda artystka nie poprzestała jednak na La pesanteur et la grâce, która, obok lektur Virginii Woolf, Anaïs Nin i wielu innych poetów, okazała się być formotwórcza dla zbudowania własnej tożsamości twórczej. Po przeprowadzeniu 1 Pisarz, Amin Maalouf, napisał libretto także w oparciu o następujące publikacje wydane przez domy wydawnicze Gallimard i Plon (Maalouf: 7): Leçons de philosophie (Weil, 1959), La connaissance surnaturelle (Weil, 1950); Écrits historiques et politiques, vol. 1–2 (Weil, 1960); Œuvres complètes, t. VI, vol. 3 (Weil, 2002). Katarzyna Kucia się do Francji w roku 1982 Saariaho kontynuowała zgłębianie biografii i pism Weil w języku oryginału. -

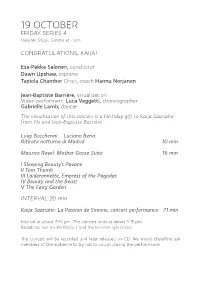

19 OCTOBER FRIDAY SERIES 4 Helsinki Music Centre at 7 Pm

19 OCTOBER FRIDAY SERIES 4 Helsinki Music Centre at 7 pm CONGRATULATIONS, KAIJA! Esa-Pekka Salonen, conductor Dawn Upshaw, soprano Tapiola Chamber Choir, coach Hannu Norjanen Jean-Baptiste Barrière, visualisation Video performers: Luca Veggetti, choreographer Gabrielle Lamb, dancer The visualisation of this concert is a birthday gift to Kaija Saariaho from Yle and Jean-Baptiste Barrière. Luigi Boccherini – Luciano Berio: Ritirata notturna di Madrid 10 min Maurice Ravel: Mother Goose Suite 16 min I Sleeping Beauty’s Pavane II Tom Thumb III Laideronnette, Empress of the Pagodas IV Beauty and the Beast V The Fairy Garden INTERVAL 20 min Kaija Saariaho: La Passion de Simone, concert performance 71 min Interval at about 7.40 pm. The concert ends at about 9.15 pm. Broadcast live on Yle Radio 1 and the Internet (yle.fi/rso) The concert will be recorded and later released on CD. We would therefore ask members of the audience to try not to cough during the performance. 1 MAURICE RAVEL KAIJA SAARIAHO: LA (1875–1937) MOTHER PASSION DE SIMONE GOOSE SUITE La Passion de Simone (2006) is an ora- Maurice Ravel composed his Mother torio by Kaija Saariaho about the life Goose (Ma Mère l’Oye), based mainly on and thoughts of Simone Weil. It is sco- ancient fairytales by Charles Perrault, red for solo soprano, choir, orchestra as a suite for two pianos in 1908 but and electronics. expanded it into a ballet three years la- The oratorio is a major addition to ter. His aim in Mother Goose was simp- the portraits of women presented by licity, though this is in fact misleading. -

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Timbral Intention

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Timbral Intention: Examining the Contemporary Performance Practice and Techniques of Kaija Saariaho’s Vocal Music A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFULLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Field of Voice Performance and Literature By Alison Wahl EVANSTON, ILLINOIS March 2017 2 ABSTRACT Kaija Saariaho’s vocal music is a rewarding challenge for a singer. Her works contain extended techniques and innovative performance practices, which allow her to create interesting and moving timbral effects. Her musical language has its foundation in her cultural identity, formed as a girl in the forests of Finland. The sound of the woods, birdsong, whispering, and wind are an integral part of Saariaho’s musical voice. Her creative use of text setting results in a highly emotional and unusual expression of poetry, although unconventional setting of words may necessitate some extra effort on the part of the performer. The extended techniques in her music are likewise emotionally driven, and include methods of fine variation in breathiness, pitch, and vibrato to create a wider palette of vocal sounds. Her use of electronics also allows her to write meaningful music with a unique musical atmosphere. In Saariaho’s collaboration with singers, she has proven to be extremely approachable and supportive, both when coaching performers of her work and developing new pieces with colleagues. Saariaho’s vocal music is more straightforward and less complex than her work for solo instruments in terms of rhythm and pitch collections; however, her innovative text setting and embracing of the wide spectrum of sound of the human voice results in a very colorful and deep musical language. -

Saariaho X Koh Saariaho X Koh

SAARIAHO X KOH SAARIAHO X KOH Jennifer Koh, violin KAIJA SAARIAHO (b. 1952) 6 Light and Matter* (13:53) 1 Tocar (6:51) Anssi Karttunen, cello Nicolas Hodges, piano Nicolas Hodges, piano Cloud Trio (13:30) 7 Aure** (5:47) Hsin-Yun Huang, viola Anssi Karttunen, cello Wilhelmina Smith, cello 2 I. Calmo, meditato (2:32) Graal théâtre (27:40) 3 II. Sempre dolce, ma Curtis 20/21 Ensemble energico, sempre a Conner Gray Covington conductor tempo (3:22) 8 I. Delicato (17:20) 4 III. Sempre energico (2:33) 9 II. Impetuoso (10:19) 5 IV. Tranquillo ma sempre molto espressivo (5:01) TT: (68:06) *World Premiere Recording **First recording of violin/cello version Program Notes INTRODUCTION by Anne Leilehua Lanzilotti Kaija Saariaho’s string writing herself has a unique relationship with is beautiful and compelling. the violin. In our conversations about At moments the sound seems this album, Saariaho recalled: to lose all its weight, the timbre brightening with flutters of harmonics, I started playing violin at the age evaporating suddenly. Other times, of six — it was my first instrument. the sound presses to the edge of force, I then started playing piano at the breaking purposefully. While Saariaho age of eight. My early memories of is known for her ability to create playing violin are filled with smells: I incredible operatic, digitally enhanced always liked a lot the smell of a rosin, soundscapes, her compositional voice and my first teacher smoked a lot, is marked by its timbral colors. Her and in fact he left me during the demand of formal structures is made lesson to play alone to go to powerful by her intimate knowledge smoke in another room. -

La Passion De Simone

FESTSPILLENEFESTSPILLENE I BERGEN PROGRAM1 2017 I BERGEN KR 20 CORNERTEATERET ONSDAG 31. MAI KL 20:00 La Passion de Simone Festspillene får offentlige tilskudd fra: Kulturrådet | Bergen kommune | Hordaland fylkeskommune Festspillambassadører: Aud Jebsen | Per Gunnar Strømberg Rasmussen v/Strømberg Gruppen | Ekaterina Mohn | Terje Lønne | Espen Galtung Døsvig v/EGD | Grieg Foundation | Yvonne og Bjarne Rieber v/Rika AS Hovedsamarbeidspartnere: BERGEN 24. MAI — 07. JUNI Redaksjon: Festspillene i Bergen / Design og konsept: ANTI Bergen, www.anti.as / INTERNATIONAL 2017 Trykkeri: Bodoni / Formgiving: Sandra Stølen FESTIVAL WWW.FIB.NO 1 FESTSPILLENE I BERGEN 3 2017 La Passion de Simone A Musical Path in Fifteen Stations CORNERTEATERET Onsdag 31. mai kl 20:00 Wednesday 31 May at 20:00 Varighet: 1 t 10 min Duration: 1:10 Kaija Saariaho musikk music Amin Maalouf tekst text La Chambre aux échos konsept, kunstnerisk ledelse concept, artistic direction Aleksi Barrière regi stage direction Clément Mao-Takacs musikalsk ledelse musical direction BIT20 Ensemble BALANSEKUNST Ingela Øien fløyte flute Eivind Sandgrind fløyte flute I DNV GL er vi opptatt av sikkerhet, kvalitet og integritet. Jonna Staas obo oboe Våre ansatte jobber hver dag mot et felles mål: En sikker Håkon Nilsen klarinett clarinet og bærekraftig fremtid. Vår rolle består ofte i å balansere Jim Lassen fagott bassoon næringslivets og samfunnets interesser – i hele verden. Danilo Kadovic horn Vi kaller det balansekunst. Aleksander Pokrywka horn Vårt samarbeid med Festspillene, en av Norges ypperste Jon Behncke trompet trumpet og mest internasjonale kulturinstitusjoner, understøtter Chris Dudley trombone nettopp denne forpliktelsen overfor samfunnet. For Trond Madsen perkusjon percussion kultur og samfunn går hånd i hånd. -

170118 Bio ENG KS

Kaija Saariaho biography Kaija Saariaho is a prominent member of a group of Finnish composers and performers who are now, in mid-career, making a worldwide impact. Born in Helsinki in 1952, she studied at the Sibelius Academy there with the pioneering modernist Paavo Heininen and, with Magnus Lindberg and others, she founded the progressive ‘Ears Open’ group. She continued her studies in Freiburg with Brian Ferneyhough and Klaus Huber, at the Darmstadt summer courses, and, from 1982, at the IRCAM research institute in Paris – the city which has been most of the time her home ever since. At IRCAM, Saariaho developed techniques of computer-assisted composition and acquired fluency in working on tape and with live electronics. This experience influenced her approach to writing for orchestra, with its emphasis on the shaping of dense masses of sound in slow transformations. Significantly, her first orchestral piece, Verblendungen (1984), involves a gradual exchange of roles and character between orchestra and tape. And even the titles of her next, linked, pair of orchestral works, Du Cristal (1989) and …à la Fumée (1990) – the latter with solo alto flute and cello, and both with live electronics – suggest their preoccupation with colour and texture. Before coming to work at IRCAM, Saariaho learned to know the French ‘spectralist’ composers, whose techniques are based on computer analysis of the sound-spectrum. This analytical approach inspired her to develop her own method for creating harmonic structures, as well as the detailed notation using harmonics, microtonaly and detailed continuum of sound extending from pure tone to unpitched noise – all features found in one of her most frequently performed works, Graal théâtre for violin and orchestra or ensemble (1994/97). -

OJAI at BERKELEY PETER SELLARS, Music DIRECTOR

OJAI MUSIC FESTIVAL OJAI AT BERKELEY PETER SELLARS, MuSIC DIRECTOR To mark the milestone 70th Ojai Music Festival, renowned director Peter Sellars returns as the 2016 music director. Sellars’ partnership with Ojai dates back to 1992, when he di- rected a daring staged version of Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du soldat with music director Pierre Boulez. The three Ojai programs presented in Berkeley this month mark the sixth year of artistic partnership between the festival and Cal Performances and represent the combined efforts of two great arts organizations committed to innovative and adventur- ous programming. Paris, Salzburg Festival, and San Francisco Opera, among others, and has established a rep- utation for bringing 20th-century and contem- porary operas to the stage, including works by Hindemith, Ligeti, Messiaen, and Stravinsky. Sellars has been a driving force in the cre- ation of many new works with longtime collab- orator John Adams, including Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer, El Niño, Doctor Atomic, A Flowering Tree, and The Gospel According to the Other Mary. Inspired by the compositions of Kaija Saariaho, Sellars has guided the creation of productions of her work that have expanded the repertoire of modern opera. Desdemona, a collaboration with Nobel Prize-winning novelist Toni Morrison and Malian composer and singer Rokia Traoré, was co-commissioned by Cal Performances and re- ceived its uS premiere here in Berkeley. Other projects with Cal Performances in- clude John Adams’ I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky, George Crumb’s The Wings of Destiny (with soprano Dawn upshaw at the 2011 Ojai Festival), and The Peter Sellars (music director, Ojai Music Festival Peony Pavilion. -

The Many Lives of Kaija Saariaho's L'amour De Loin

Cori Ellison “Mais c’est chaque fois la première fois”: The Many Lives of Kaija Saariaho’s L’amour de loin Since its world premiere at the Salzburg Festival in 2000, L’amour de loin, Kaija Saariaho’s first opera, has been presented in eight different productions, in fourteen cities on two continents—easily setting a record for operas of the new millennium. Its popularity is not surprising in light of its extraordinary musical beauty, richness, and originality, as well as the depth and universality of its dramatic themes. Yet L’amour de loin is radical in its dramaturgy and challenging for both audiences and interpreters. Though based on historical characters, L’amour de loin conjures a mythological resonance reminiscent of similarly pioneering operas like Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, and Messiaen’s Saint François d’Assise. Like them, it is minimal in event and maximal in ideas, colors, and emotions, defying conventional Western operatic dramaturgy to bravely shift the dramatic onus to a unique and opulent sound world. And like those operas, L’amour de loin invites and inspires myriad theatrical interpretations of prodigious imagination and breathtaking diversity. The world-premiere production of L’amour de loin (Salzburg 2000/Chatelet 2002/Santa Fe 2002/Helsinki 2004) presented the work in the typically poetic, elemental, hieratic style of Peter Sellars. Subsequent productions have ranged widely in style and emphasis, from the entirely animated production by visual artists Ingar Dragset and Michael Elmgreen (Bergen International Festival 2008), and the visually spectacular version by Daniele Finzi Pasca of Cirque du Soleil (English National Opera 2009, Vlaamse Opera 2010, Canadian Opera Company 2012), to the more terrestrial interpretations of Olivier Tambosi in Bern (2001) and Steffen Piontek in Rostock (2008).