The Oscholars ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recasting Gender

RECASTING GENDER: 19TH CENTURY GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS IN THE LIVES AND WORKS OF ROBERT AND CLARA SCHUMANN A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Shelley Smith August, 2009 RECASTING GENDER: 19TH CENTURY GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS IN THE LIVES AND WORKS OF ROBERT AND CLARA SCHUMANN Shelley Smith Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. James Lynn _________________________________ _________________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _________________________________ _________________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. THE SHAPING OF A FEMINIST VERNACULAR AND ITS APPLICATION TO 19TH-CENTURY MUSIC ..............................................1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 The Evolution of Feminism .....................................................................................3 19th-Century Gender Ideologies and Their Encoding in Music ...............................................................................................................8 Soundings of Sex ...................................................................................................19 II. ROBERT & CLARA SCHUMANN: EMBRACING AND DEFYING TRADITION -

17.2. Cylinders, Ed. Discs, Pathes. 7-26

CYLINDERS 2M WA = 2-minute wax, 4M WA= 4-minute wax, 4M BA = Edison Blue Amberol, OBT = original box and top, OP = original descriptive pamphlet. Repro B/T = Excellent reproduction Edison orange box and printed top. All others in clean, used boxes. Any mold on wax cylinders is always described. All cylinders not described as in OB (original box with generic top) or OBT (original box and original top) are boxed (most in good quality boxes) with tops and are standard 2¼” diameter. All grading is visual and refers to the cylinders rather than the boxes. Any major box problems are noted. CARLO ALBANI [t] 1039. Edison BA 28116. LA GIOCONDA: Cielo e mar (Ponchielli). Repro B/T. Just about 1-2. $30.00. MARIO ANCONA [b] 1001. Edison 2M Wax B-41. LES HUGUENOTS: Nobil dama (Meyerbeer). Announced by Ancona. OBT. Just about 1-2. $75.00. BLANCHE ARRAL [s] 1007. Edison Wax 4-M Amberol 35005. LE COEUR ET LA MAIN: Boléro (Lecocq). This and the following two cylinders are particularly spirited performances. OBT. Slight box wear. Just about 1-2. $50.00. 1014. Edison Wax 4-M Amberol 35006. LA VÉRITABLE MANOLA [Boléro Espagnole] (Bourgeois). OBT. Just about 1-2. $50.00. 1009. Edison Wax 4-M Amberol 35019. GIROLFÉ-GIROFLA: Brindisi (Lecocq). OBT. Just about 1-2. $50.00. PAUL AUMONIER [bs] 1013. Pathé Wax 2-M 1111. LES SAPINS (Dupont). OB. 2. $20.00. MARIA AVEZZA [s]. See FRANCESCO DADDI [t] ALESSANDRO BONCI [t] 1037. Edison BA 29004. LUCIA: Fra poco a me ricovero (Donizetti). -

Mala Vita Melodramma in Tre Atti

MALA VITA MELODRAMMA IN TRE ATTI versi di Nicola Daspuro musica di Umberto Giordano testi a cura di Agostino Pio Ruscillo COMUNE di FOGGIA Teatro comunale «U. Giordano» 2002 AVVERTENZA INDICE Ripubblichiamo qui senza varianti, se non di ordine tipografico, il libretto stampato in occasione della prima rappresentazione dell’opera; di seguito la descrizione del frontespizio: MALA VITA / MELODRAMMA IN TRE ATTI / versi di / N. DASPURO / musica di / UMBERTO GIORDANO / R. Teatro Argentina / Sta- INTRODUZIONE gione Carnevale-Quaresima 1892 / IMPRESA DEL MARCHESE Mala vita di Daspuro-Giordano: melodramma GINO MONALDI / [fregio] / MILANO / EDOARDO SONZOGNO, EDI- TORE / 14 - Via Pasquirolo - 14 / 1892. tardoromantico nel contenitore del teatro musicale verista 5 Durante la fase di collazione tra il libretto (LI) e lo spartito (SP) della Indicazioni bibliografiche 19 riduzione per canto e pianoforte (a cura di Alessandro Longo, Mila- no, Sonzogno, 1892) sono state registrate varianti significative e se- Note al testo 21 gnalate opportunamente nelle Note al libretto. LIBRETTO Elenco dei personaggi 31 Atto primo 33 Atto secondo 53 Atto terzo 71 Note al libretto 81 Grafica di copertina: Free point Impaginazione: RAgo Interpreti della rappresetnzione in epoca moderna © 1892, EDOARDO SONZOGNO (Foggia, Teatro «U. Giordano», 12 e 14 dicembre 2002) 95 © 2002, CASA MUSICALE SONZOGNO di Piero Ostali Via Bigli, 11 – 20121 Milano INTRODUZIONE Mala vita di Daspuro-Giordano: melodramma tardoromantico nel contenitore del teatro musicale verista. «Cominciato Napoli 8 Dicembre 1890».1 Con questa frase il ventitreenne Umberto Giordano, neodiplomato in compo- sizione presso il Conservatorio di S. Pietro a Majella di Napo- li, nella classe del maestro Paolo Serrao,2 segna indelebilmente il manoscritto degli abbozzi di Mala vita. -

Debussy's Pelléas Et Mélisande

Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore Pelléas et Mélisande is a strange, haunting work, typical of the Symbolist movement in that it hints at truths, desires and aspirations just out of reach, yet allied to a longing for transcendence is a tragic, self-destructive element whereby everybody suffers and comes to grief or, as in the case of the lovers, even dies - yet frequent references to fate and Arkel’s ascribing that doleful outcome to ineluctable destiny, rather than human weakness or failing, suggest that they are drawn, powerless, to destruction like moths to the flame. The central enigma of Mélisande’s origin and identity is never revealed; that riddle is reflected in the wispy, amorphous property of the music itself, just as the text, adapted from Maeterlinck’s play, is vague and allusive, rarely open or direct in its expression of the characters’ velleities. The opera was highly innovative and controversial, a gateway to a new style of modern music which discarded and re-invented operatic conventions in a manner which is still arresting and, for some, still unapproachable. It is a work full of light and shade, sunlit clearings in gloomy forest, foetid dungeons and sea-breezes skimming the battlements, sparkling fountains, sunsets and brooding storms - all vividly depicted in the score. Any francophone Francophile will delight in the nuances of the parlando text. There is no ensemble or choral element beyond the brief sailors’ “Hoé! Hisse hoé!” offstage and only once do voices briefly intertwine, at the climax of the lovers' final duet. -

'Koanga' and Its Libretto William Randel Music & Letters, Vol. 52, No

'Koanga' and Its Libretto William Randel Music & Letters, Vol. 52, No. 2. (Apr., 1971), pp. 141-156. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0027-4224%28197104%2952%3A2%3C141%3A%27AIL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-B Music & Letters is currently published by Oxford University Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/oup.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Sep 22 12:08:38 2007 'KOANGA' AND ITS LIBRETTO FREDERICKDELIUS arrived in the United States in 1884, four years after 'The Grandissimes' was issued as a book, following its serial run in Scribner's Monthh. -

Unit 7 Romantic Era Notes.Pdf

The Romantic Era 1820-1900 1 Historical Themes Science Nationalism Art 2 Science Increased role of science in defining how people saw life Charles Darwin-The Origin of the Species Freud 3 Nationalism Rise of European nationalism Napoleonic ideas created patriotic fervor Many revolutions and attempts at revolutions. Many areas of Europe (especially Italy and Central Europe) struggled to free themselves from foreign control 4 Art Art came to be appreciated for its aesthetic worth Program-music that serves an extra-musical purpose Absolute-music for the sake and beauty of the music itself 5 Musical Context Increased interest in nature and the supernatural The natural world was considered a source of mysterious powers. Romantic composers gravitated toward supernatural texts and stories 6 Listening #1 Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique (4th mvmt) Pg 323-325 CD 5/30 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QwCuFaq2L3U 7 The Rise of Program Music Music began to be used to tell stories, or to imply meaning beyond the purely musical. Composers found ways to make their musical ideas represent people, things, and dramatic situations as well as emotional states and even philosophical ideas. 8 Art Forms Close relationship Literature among all the art Shakespeare forms Poe Bronte Composers drew Drama inspiration from other Schiller fine arts Hugo Art Goya Constable Delacroix 9 Nationalism and Exoticism Composers used music as a tool for highlighting national identity. Instrumental composers (such as Bedrich Smetana) made reference to folk music and national images Operatic composers (such as Giuseppe Verdi) set stories with strong patriotic undercurrents. Composers took an interest in the music of various ethnic groups and incorporated it into their own music. -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

Korngold Violin Concerto String Sextet

KORNGOLD VIOLIN CONCERTO STRING SEXTET ANDREW HAVERON VIOLIN SINFONIA OF LONDON CHAMBER ENSEMBLE RTÉ CONCERT ORCHESTRA JOHN WILSON The Brendan G. Carroll Collection Erich Wolfgang Korngold, 1914, aged seventeen Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 – 1957) Violin Concerto, Op. 35 (1937, revised 1945)* 24:48 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel 1 I Moderato nobile – Poco più mosso – Meno – Meno mosso, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Poco meno – Tempo I – [Cadenza] – Pesante / Ritenuto – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Meno, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Meno – Più mosso 9:00 2 II Romanze. Andante – Meno – Poco meno – Mosso – Poco meno (misterioso) – Avanti! – Tranquillo – Molto cantabile – Poco meno – Tranquillo (poco meno) – Più mosso – Adagio 8:29 3 III Finale. Allegro assai vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco meno (maestoso) – Fließend – Più tranquillo – Più mosso. Allegro – Più mosso – Poco meno 7:13 String Sextet, Op. 10 (1914 – 16)† 31:31 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Herrn Präsidenten Dr. Carl Ritter von Wiener gewidmet 3 4 I Tempo I. Moderato (mäßige ) – Tempo II (ruhig fließende – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III. Allegro – Tempo II – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Tempo II – Allmählich fließender – Tempo III – Wieder Tempo II – Tempo III – Drängend – Tempo I – Tempo III – Subito Tempo I (Doppelt so langsam) – Allmählich fließender werdend – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo I – Tempo II (fließend) – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III – Ruhigere (Tempo II) – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Sehr breit – Tempo II – Subito Tempo III 9:50 5 II Adagio. Langsam – Etwas bewegter – Steigernd – Steigernd – Wieder nachlassend – Drängend – Steigernd – Sehr langsam – Noch ruhiger – Langsam steigernd – Etwas bewegter – Langsam – Sehr breit 8:27 6 III Intermezzo. -

The Role of Contemporary Music in Instrumental Education

The role of contemporary music in instrumental education Mark Rayen Candasmy Supervisor Per Kjetil Farstad This Master’s Thesis is carried out as a part of the education at the University of Agder and is therefore approved as a part of this education. However, this does not imply that the University answers for the methods that are used or the conclusions that are drawn. University of Agder, 2011 Faculty of fine arts Department of music Abstract The role of contemporary music in instrumental education discusses the necessity of renewing the curriculum of all musical studies that emphasize performance and the development of the student's instrumental abilities. A portrait of Norwegian composer Ørjan Matre is included to help exemplify the views expressed, as well as the help of theoretical analysis. Key words: contemporary music, education, musicology, ørjan matre, erich wolfgang korngold, pedagogy The role of contemporary music in instrumental education is divided into six chapters. Following the introduction, the second chapter discusses the state of musical critique and musicology, describing the first waves of modernism at the turn of the century (19 th /20 th ) and relating it to the present reality and state of contemporary music. Conclusively, it suggests possibilities of bettering the situation. The third chapter discusses the controversial aspects of Erich Wolfgang Korngold's music and life, relating it to the turbulence of the musical life during his lifetime. Studying Korngold is a unique way to outline the contradictions within Western art music that were being established during his career. The fourth chapter is a portrait of Norwegian composer Ørjan Matre and includes an analysis of his work " Handel Mixtape s". -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE COMPLETED SYMPHONIC COMPOSITIONS OF ALEXANDER ZEMLINSKY DISSERTATION Volume I Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert L. -

Die Seejungfrau Zemlinsky

Zemlinsky Die Seejungfrau NETHERLANDS PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA MARC ALBRECHT Cover image: derived from Salted Earth (2017), cling to them. Has Zemlinsky’s time come? photo series by Sophie Gabrielle and Coby Baker Little mermaid in a fin-de-siècle https://www.sophiegabriellephoto.com garment Or is the question now beside the point? http://www.cobybaker.com In that Romantic vein, the Lyric Symphony ‘I have always thought and still believe remains Zemlinsky’s ‘masterpiece’: frequently that he was a great composer. Maybe performed, recorded, and esteemed. His his time will come earlier than we think.’ operas are now staged more often, at least Arnold Schoenberg was far from given to in Germany. In that same 1949 sketch, Alexander von Zemlinsky (1871-1942) exaggerated claims for ‘greatness’, yet he Schoenberg praised Zemlinsky the opera could hardly have been more emphatic in composer extravagantly, saying he knew the case of his friend, brother-in-law, mentor, not one ‘composer after Wagner who could Die Seejungfrau (Antony Beaumont edition 2013) advocate, interpreter, and, of course, fellow satisfy the demands of the theatre with Fantasy in three movements for large orchestra, after a fairy-tale by Andersen composer, Alexander Zemlinsky. Ten years better musical substance than he. His ideas, later, in 1959, another, still more exacting his forms, his sonorities, and every turn of the 1 I. Sehr mäßig bewegt 15. 56 modernist critic, Theodor W. Adorno, wrote music sprang directly from the action, from 2 II. Sehr bewegt, rauschend 17. 06 in surprisingly glowing terms. Zemlinsky the scenery, and from the singers’ voices with 3 III. -

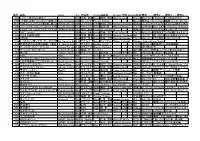

番号 曲名 Name インデックス 作曲者 Composer 編曲者 Arranger作詞

番号 曲名 Name インデックス作曲者 Composer編曲者 Arranger作詞 Words出版社 備考 備考2 備考3 備考4 595 1 2 3 ~恋がはじまる~ 123Koigahajimaru水野 良樹 Yoshiki鄕間 幹男 Mizuno Mikio Gouma ウィンズスコアWSJ-13-020「カルピスウォーター」CMソングいきものがかり 1030 17世紀の古いハンガリー舞曲(クラリネット4重奏)Early Hungarian 17thDances フェレンク・ファルカシュcentury from EarlytheFerenc 17th Hungarian century Farkas Dances from the Musica 取次店:HalBudapest/ミュージカ・ブダペスト Leonard/ハル・レナード編成:E♭Cl./B♭Cl.×2/B.Cl HL50510565 1181 24のプレリュードより第4番、第17番24Preludes Op.28-4,1724Preludesフレデリック・フランソワ・ショパン Op.28-4,17Frédéric福田 洋介 François YousukeChopin Fukuda 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2019年2月スコアは4番と17番分けてあります 840 スリー・ラテン・ダンス(サックス4重奏)3 Latin Dances 3 Latinパトリック・ヒケティック Dances Patric 尾形Hiketick 誠 Makoto Ogata ブレーンECW-0010Sax SATB1.Charanga di Xiomara Reyes 2.Merengue Sempre di Aychem sunal 3.Dansa Lationo di Maria del Real 997 3☆3ダンス ソロトライアングルと吹奏楽のための 3☆3Dance福島 弘和 Hirokazu Fukushima 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2017年6月号サンサンダンス(日本語) スリースリーダンス(英語) トレトレダンス(イタリア語) トゥワトゥワダンス(フランス語) 973 360°(miwa) 360domiwa、NAOKI-Tmiwa、NAOKI-T西條 太貴 Taiki Saijyo ウィンズスコアWSJ-15-012劇場版アニメ「映画ドラえもん のび太の宇宙英雄記(スペースヒーローズ)」主題歌 856 365日の紙飛行機 365NichinoKamihikouki角野 寿和 / 青葉 紘季Toshikazu本澤なおゆき Kadono / HirokiNaoyuki Honzawa Aoba M8 QH1557 歌:AKB48 NHK連続テレビ小説『あさが来た』主題歌 685 3月9日 3Gatu9ka藤巻 亮太 Ryouta原田 大雪 Fujimaki Hiroyuki Harada ウィンズスコアWSL-07-0052005年秋に放送されたフジテレビ系ドラマ「1リットルの涙」の挿入歌レミオロメン歌 1164 6つのカノン風ソナタ オーボエ2重奏Six Canonic Sonatas6 Canonicゲオルク・フィリップ・テレマン SonatasGeorg ウィリアム・シュミットPhilipp TELEMANNWilliam Schmidt Western International Music 470 吹奏楽のための第2組曲 1楽章 行進曲Ⅰ.March from Ⅰ.March2nd Suiteグスタフ・ホルスト infrom F for 2ndGustav Military Suite Holst