China: Persecution of a Protestant Sect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prediction of Continuous Rain Disaster in Henan Province Based on Markov Model

Hindawi Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society Volume 2020, Article ID 7519215, 6 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7519215 Research Article Prediction of Continuous Rain Disaster in Henan Province Based on Markov Model Xiaoxiao Zhu , Shuhua Zhang, and Bingjun Li College of Information and Management Science, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou 450002, China Correspondence should be addressed to Bingjun Li; [email protected] Received 24 July 2019; Revised 21 February 2020; Accepted 27 February 2020; Published 12 September 2020 Academic Editor: Seenith Sivasundaram Copyright © 2020 Xiaoxiao Zhu et al. /is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Continuous rain disasters occur frequently, which seriously affect maize yield. However, the research on predicting continuous rain disasters is very limited. Taking the maize in Henan Province as an example, the Markov model is used to predict the occurrence of continuous rain in the middle growth and late growth stages (flowering and filling stages) of 13 cities in Henan Province. /e results showed that the maize in Henan Province would suffer from continuous rain disaster in 2020 and 2021. Finally, combined with the prediction results, policy recommendations for maize growth in Henan Province are proposed to ensure stable and high yield of maize. 1. Introduction and seedling rot. Autumn crops are in the stage of filling and maturity, and frequent occurrence of rain will seriously Henan Province is an important major grain-producing area affect the yield and quality of crops. -

A Study on the Soil and Water Conservation Effect of Larix Kaernpferi (Sieb

12th ISCO Conference Beijing 2002 A Study on the Soil and Water Conservation Effect of Larix kaernpferi (Sieb. et Zucc.) Forest Zhao Yong Li Shuren and Wu Mingzuo Environment Department, Henan Agriculture University, Zhengzhou, Henan Province E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The direct runoff and soil erosion was observed in the Larix kaernpferi forest that was man planted with two different site preparation methods for contrasting. The results showed that the hole or strip site preparation methods has obvious effects to decrease the direct runoff and soil erosion. The hole site preparation method has the best effect on decreasing direct runoff by 34% and soil erosion by 42%. The two different site preparation methods also had obvious effects on decreasing the washing of nutrient element by 79.75kg hm–2 a–1— 135.40kg hm–2 a–1. Keywords: soil and water conservation, site preparation, direct runoff, soil nutrient, Larix kaernpferi Forest can not only affect soil physic and chemistry traits, but also regulate rainfall’s distribution and water flow process. The study of forest ecology now put much emphasis on the forest effects on decreasing soil erosion and the change of soil characteristics. The study on these effects of man-planted Larix kaernpferi forest using two different site preparation methods was carried on in 1993—1995 in Longyuwan forestry center in Luanchuan county, Henan province. The amount of direct runoff, soil erosion and soil nutrient elements were observed in the fixed field. 1 Study site outlines The study site is lying in the Longyuwan forestry center in Luanchuan county, Henan province, locating at 111 35 E and 33 45 . -

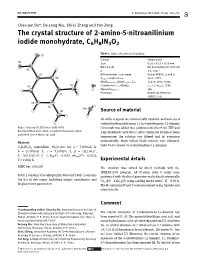

The Crystal Structure of 2-Amino-5-Nitroanilinium Iodide Monohydrate, C6H8IN3O2

Z. Kristallogr. NCS 2021; 236(4): 725–726 Chao-Jun Du*, De-Long Niu, Shi-Li Zheng and Yan Zeng The crystal structure of 2-amino-5-nitroanilinium iodide monohydrate, C6H8IN3O2 Table : Data collection and handling. Crystal: Yellow block Size: . × . × . mm Wavelength: Mo Kα radiation (. Å) μ: . mm− Diffractometer, scan mode: Bruker APEX-II, φ and ω θmax, completeness: .°,>% N(hkl)measured,N(hkl)unique, Rint: , , . Criterion for Iobs, N(hkl)gt: Iobs > σ(Iobs), N(param)refined: Programs: Bruker [], Olex [], SHELX [, ] Source of material All of the reagents are commercially available and were used without further purification. 1.53 g 4-nitrobenzene-1,2-diamine https://doi.org/10.1515/ncrs-2021-0058 (10mmol)wasaddedtoasolutionmixedby9mLTHFand Received February 8, 2021; accepted February 25, 2021; 1 mL hydroiodic acid (40%). Afterstirringfor10minatroom published online March 19, 2021 temperature, the solution was filtered and let evaporate automatically. Many yellow block crystals were obtained, Abstract yield 74.6% (based on 4-nitrobenzene-1,2-diamine). C6H8IN3O2, monoclinic, P21/n (no. 14), a = 7.0704(3) Å, b = 15.7781(6) Å, c = 9.1495(4) Å, β = 112.114(1)°, 3 2 V = 945.61(7) Å , Z =4,Rgt(F) = 0.0187, wRref(F ) = 0.0522, T = 150(2) K. Experimental details CCDC no.: 2065269 The structure was solved by direct methods with the SHELXS-2018 program. All H-atoms from C atoms were Table 1 contains crystallographic data and Table 2 contains positioned with idealized geometry and refined isotropically the list of the atoms including atomic coordinates and (Uiso(H) = 1.2Ueq(C)) using a riding model with C–H=0.95Å. -

Highlightes Pf Environmental Impact Assessment

E-174 VOL. 6 Public Disclosure Authorized National Highway Project Upgrading Xinxiang--Zhengzhou class I ° highway to Expressway Standard Highlightes pf Environmental Impact Public Disclosure Authorized Assessment (Third Revised Version) SCAt4INEDV1E6F Public Disclosure Authorized FILE(Cola g LrG r 6WTENW SA P Henan Provincial Environmental Protection Institute Public Disclosure Authorized October, 1998 1. Description of the Proposed Project 1) Upgrading work on Xinxiang--Zhengzhou class I highway is a temporary work to achieve original capacity of the existing class I highway before building of Xinxiang-- zhengzhou Expressway. The proposed section for upgrading, till year 2004 , will take two in one" status between BeiJing--shenzhen National Trunk Highway and National highway 107 . After year 2004 upon completion of Xinxiang--zhengzhou expressway and the second Zhengzhou Yellow River Bridge at new alternative alignment , the upgraded section will mainly take the traffic volume on National highway 107 2) Based upon the recommended alignment , Upgrading work on Xinxiang--zhengzhou class I highway consist of : North section of the Yellow River Bridge(starting from the terminal point on Anxin expressway ending to the north bank of YR ): this section is 39.326km long with fully-access-controled and service road being built . There need to be newly built 1 simple interchange, 24 overpass separation interchanges, to reconstruct 1 toll station, 9 passageways ,newly built 9 small bridges, and 7 middle bridges ,150 culverts as well as 29.848km of approach road and service road and 43.5km of continuous road ; the section from the north bank of YR to Longhai railway interchange (south section.to north bank of YR involves the Yellow River Bridge itself ): this section is 30.447km in total and will be provided with barrier (fence) for isolating motorized and non-motorized vehicle lane . -

Henan Sustainable Livestock Farming and Product Safety Demonstration

Environmental Monitoring Report 5th Semestral Report Project Number: 46081-002 February 2019 PRC: Henan Sustainable Livestock Farming and Product Safety Demonstration Project Prepared by Henan Provincial Project Management Office for the Henan Provincial Government and the Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Director, Management or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Project Number: L3296 February 2019 PRC: Henan sustainable Livestock Farming and Product Safety Demonstration Project Prepared by Henan Provincial Project Management Office for the Henan Provincial Government and the Asian Development Bank. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s members, Board of Directors, Magement, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Report Purpose and Rationale 1 B. Project Objective and Components 1 C. Project Implementation Progress 3 II. INSTITUTIONAL SETUP AND RESPONSIBILITIES FOR EMP IMPLEMENTATION 7 A. Institutional responsibilities for environmental management 7 B. Incorporation of Environmental Requirements into Project Contractual Arrangements 12 III. -

Reorganization and Corporate Structure

REORGANIZATION AND CORPORATE STRUCTURE History and Development We were established on December 22, 1999 under the name of LLMG, as a limited liability company wholly-owned by the People’s Government of Luanchuan County (which held the interest on behalf of the People’s Government of Luoyang City) following the approval of the merger of two enterprises, namely, LLMC and LCMCC on August 18, 1998 by the People’s Government of Luoyang City. Our registered capital was RMB251 million upon establishment. Immediately prior to the merger, both LLMC and LCMCC were principally engaged in mining, flotation, roasting, smelting and sale of molybdenum products. Following the establishment of LLMG, we expanded our open-pit mining operations. Our ore production reached 8,000 tpd by the end of 2001. In 2002, Luomu Group Refining commenced its operations to produce molybdenum oxide and ferromolybdenum. To accommodate the mining expansion, we doubled our daily ore processing capacity from 8.0 Kt in 2002 to approximately 15.0 Kt by the end of 2004. As part of our corporate restructuring, we disposed of some of our businesses during the years 2003 and 2004 to streamline our business operations. In September 2004, after receiving the approvals issued by the People’s Government of Luanchuan County approving the reorganization of LLMG and CFCH to subscribe shares in LLMG, we entered into an agreement with CFCH (‘‘Subscription Agreement’’) and increased our registered capital to RMB280,020,000. Luoyang SASAC reconfirmed our 2004 reorganization by ‘‘The letter on the reorganization of Luoyang Luanchuan Molybdenum Group Co., Ltd in 2004’’ in November 2006 and ‘‘The confirmation letter on the reorganization and capital increase of China Molybdenum Co., Ltd.’’ in January 2007. -

2019 International Religious Freedom Report

CHINA (INCLUDES TIBET, XINJIANG, HONG KONG, AND MACAU) 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary Reports on Hong Kong, Macau, Tibet, and Xinjiang are appended at the end of this report. The constitution, which cites the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and the guidance of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought, states that citizens have freedom of religious belief but limits protections for religious practice to “normal religious activities” and does not define “normal.” Despite Chairman Xi Jinping’s decree that all members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) must be “unyielding Marxist atheists,” the government continued to exercise control over religion and restrict the activities and personal freedom of religious adherents that it perceived as threatening state or CCP interests, according to religious groups, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and international media reports. The government recognizes five official religions – Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Protestantism, and Catholicism. Only religious groups belonging to the five state- sanctioned “patriotic religious associations” representing these religions are permitted to register with the government and officially permitted to hold worship services. There continued to be reports of deaths in custody and that the government tortured, physically abused, arrested, detained, sentenced to prison, subjected to forced indoctrination in CCP ideology, or harassed adherents of both registered and unregistered religious groups for activities related to their religious beliefs and practices. There were several reports of individuals committing suicide in detention, or, according to sources, as a result of being threatened and surveilled. In December Pastor Wang Yi was tried in secret and sentenced to nine years in prison by a court in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, in connection to his peaceful advocacy for religious freedom. -

Annual Report

Central China Securities AR2018 Cover 29.2mm_output.pdf 1 8/4/2019 下午7:33 C e n t r a l C 中州証 中州証券 h i n a S e Central China Securities Co., Ltd. c u r (a joint stock company incorporated in 2002 in Henan Province, the People's Republic of China with limited liability i t i under the Chinese corporate name “ 中原證券股份有限公司 ” and carrying on business in Hong Kong as “ 中州證券 ”) e s 券 (2002 年於中華人民共和國河南省成立的股份有限公司,中文公司名稱為「中原證券股份有限公司」, C 在香港以「中州證券」名義開展業務) o . Stock Code 股份代號 : 01375 , L t d . C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Annual Report 2018 年報 中州証券 年報 2018 Central China Securities Co., Ltd. Annual Report IMPORTANT NOTICE The Board and the Supervisory Committee and the Directors, Supervisors and senior management of the Company warrant the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of contents of this report and that there is no false representation, misleading statement contained herein or material omission from this report, for which they will assume joint and several liabilities. This report has been considered and approved at the Sixth Meeting of the Sixth Session of the Board and the Fifth Meeting of the Sixth Session of the Supervisory Committee where all Directors and Supervisors attended the respective meeting. The annual financial statements for 2018 prepared by the Company in accordance with the International Financial Reporting Standards and China’s Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises have been audited by PricewaterhouseCoopers and ShineWing Certified Public Accountants (Special General Partnership), respectively with respective standard unqualified audit report issued to the Company. -

Here Discharged Water Is Treated with Limewater, Purification Agents, and Five-Stage Sedimentation, Bringing It up to Chinese National Standards

希尔威金属矿业有限公司 2 0 2 0 可持续发展报告 SILVERCORP METALS INC. Fiscal 2020 Sustainability Report About This Report About This Report Time Period This report mainly focuses on our Fiscal Year 2020 (April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020), and may refer to information of other years in order to strengthen the comparison of statistics. Entities Covered in this Report This report covers the headquarters and subsidiaries of Silvercorp Metals Inc. For convenience of expression and simplicity, Silvercorp Metals Inc. is also referred to as Silvercorp, the Company, or we. Its subsidiaries, Henan Found Mining Co. Ltd. and Guangdong Found Mining Co. Ltd., are also referred to as Henan Found and Guangdong Found respectively. Data This annual report is the first such report issued by the Company, and the information provided has not yet been verified by an external auditor. This report aims at reflecting the economic, environmental and social performance of the Company. Reference Standards This report is prepared based on the Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI) Standards: Core option, the Guide on Preparation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reports of Chinese Enterprises (CASS-CSR 4.0) and the Guide on Preparation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reports of Chinese Enterprises (CASS-CSR 4.0) - Mining Industry, both published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and the Guide for Business Action on SDGs by the UN Global Compact. Availability This report is available in both printed copies and an electronic version available on our official website. Requests for printed copies of this report should be addressed to Silvercorp Metals Inc. Address: Suite 1750-1066 W. -

World Bank Document

February 28, 2000 Governor Li Kegiang People’s Government of Henan Province Public Disclosure Authorized No. 10 Wei-er road Zhengzhou 450003 Henan Province People’s Republic of China Dear Governor Li: RE: National Highway Project (LN 3748-CHA) Amendment to Henan Project Agreement 1. I refer to (i) the Loan Agreement between People’s Republic of China (the Borrower) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the Bank) dated July 20, 1994 for the above-mentioned Project, as amended by a Letter of Amendment dated August 18, 1997 (together the Loan Agreement), and (ii) the Project Agreement between the Bank and Henan Province (Henan) dated July 20, 1994, for the Henan Part of the Project (the Henan Project Agreement). I also refer to the letter dated January 31, 2000 from Mr. Wu Gang, Deputy Director-General, International Department, Ministry of Finance, on behalf of the Borrower, requesting a re-allocation Public Disclosure Authorized of the proceeds of the Loan to allow the upgrading of the Xinxiang- Zhengzhou Highway to be included in the Henan Part of the Project. 2. I am pleased to inform you that the Bank hereby concurs with the Borrower’s proposal to modify the Project and re-allocate the proceeds of the Loan. To give effect to such proposal, the Bank hereby agrees to amend the Project Agreement in accordance with the following paragraphs. 3. Section 1.01 of the Henan Project Agreement is amended as follows: “Section 1.01. […] (a) “Environmental Action Plan” means collecctively (i) the Anyang-Xinxiang Expressway Environmental Protection Measures, Management and Monitoring Action Plan, dated September 1993, and (ii) the Environmental Action Plan for the Upgrading Works Between Xinxiang and Zhengzhou, dated November 1998, both prepared by Henan Environmental Protection Research Institute; as the same may be revised from time to time with the prior agreement of the Bank. -

HR Water Consumption Marginal Benefits and Its Spatial–Temporal Disparities in Henan Province, China

Desalination and Water Treatment 114 (2018) 101–108 www.deswater.com May doi: 10.5004/dwt.2018.22345 HR water consumption marginal benefits and its spatial–temporal disparities in Henan Province, China Subing Lüa,b, Huan Yanga, Fuqiang Wanga,b,c,*, Pingping Kanga,b aNorth China University of Water Resources and Electric Power, Henan Province 450046, China, email: [email protected] (F. Wang) bCollaborative Innovation Center of Water Resources Efficient Utilization and Support Engineering, Henan Province 450046, China cHenan Key Laboratory of Water Environment Simulation and Treatment, Henan Province 450046, China Received 7 November 2017; Accepted 4 February 2018 abstract Water is one of the essential resources to production and living. Agriculture, industry, and living are considered as the direct water consumption. This paper employs the concept of marginal product value to estimate the water consumption marginal benefits in Henan Province. We use data on agri- cultural water consumption, industrial water consumption, and domestic water consumption of 18 cities in Henan Province surveyed from 2006 to 2013 and considered the Cobb–Douglas production function. The results showed that, during the study period, except for the marginal benefit of agricul- ture in high developed area, the industrial and domestic water use increased, and the industrial and domestic water use benefits were much higher than agricultural. At the same time, the benefit of the developed area was higher than the developing area. The benefits of agricultural water consumption and industrial water consumption in high developed area have made great improvements gradually, while benefits in low developed area have made small changes; but the benefits of domestic water con- sumption presented the opposite trend. -

Henan IEE TA

Initial Environmental Examination August 2015 PRC: Henan Sustainable Livestock Farming and Product Safety Demonstration Project Prepared by the Henan Provincial Government for the Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 25 August 2015) Currency unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.1562 $1.00 = CNY6.4040 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank GHG greenhouse gas BOD5 5-day biochemical oxygen demand GRM grievance redress mechanism CNY Chinese yuan HPG Henan provincial government COD chemical oxygen demand IA implementing agency DO dissolved oxygen MOE Ministry of Environment EA executing agency PMO project management office EIA environmental impact assessment PPE project participating enterprise EIR environmental impact report RP resettlement plan EIT environmental impact table SOE state-owned enterprise EMP environmental management plan SPS Safeguard Policy Statement EPB environmental protection bureau WHO World Health Organization FSR feasibility study report WRB water resources bureau FYP five-year plan WTP water treatment plant GDP gross domestic product WWTP wastewater treatment plant WEIGHTS AND MEASURES oC degree centigrade m2 square meter dB decibel m3/a cubic meter per annum km kilometer m3/d cubic meter per day km2 square kilometer mg/kg milligram per kilogram kW kilowatt mg/l milligram per liter L liter mg/m3 milligram per cubic meter m meter t ton t/a ton per annum NOTE (i) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website.