The Canoe Yawl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cruising History

Portland Yacht Club A History of Cruising Activity The Portland Yacht Club traces its routes to a weekend cruise to Boothbay Harbor by several Portlanders in the mid 1860's. This venture was the impetus that began a discussion about forming a yacht club. This was followed by a meeting in June 1868, at which time they decided if they could sign 100 members they would move forward. On April 26, 1869 their initiative was rewarded with the creation of the Portland Yacht Club. During the first year, the club held another cruise to Boothbay Harbor. Departing Boothbay, they went up the Sasanoa (hopefully with the tide) to Bath. The next day they sailed down the Kennebec River (again hopefully with a fair tide) to Jewel Island where “a Grand Clam Bake” was held. The entire three day cruise was enshrouded in fog and supposedly continued for the next 34 years (some things never change). But, think of the seamanship and navigation skills required to ply those waters in a vessel with no power other than the wind while using less than reliable charts, compass, watch and taffrail log. Present day cruisers are now quite spoiled with the electronics available. In 1873 the club held both a spring and fall cruise along with 30 boats participating in Portland's July 4th Celebration. The spring cruise of 1879 included 4 schooners and 2 sloops. They departed the club at 1000 and arrived in Wiscasset at 1620. The sloop Vif went aground on Merrill's Ledge in the Sheepscot. As the saying goes, “There are two types of sailors in Maine, those that have been aground and those that will go aground”. -

Britannia Yacht Club New Member's Guide Your Cottage in the City!

Britannia Yacht Club New Member’s Guide Your Cottage in the City! Britannia Yacht Club 2777 Cassels St. Ottawa, Ontario K2B 6N6 613 828-5167 [email protected] www.byc.ca www.facebook.com/BYCOttawa @BYCTweet Britannia_Yacht_Club Welcome New BYC Member! Your new membership at the Britannia Yacht Club is highly valued and your fellow members, staff and Board of Directors want you to feel very welcome and comfortable as quickly as possible. As with all new things, it does take time to find your way around. Hopefully, this New Member’s Guide answers the most frequently asked questions about the Club, its services, regulations, procedures, etiquette, etc. If there is something that is not covered in this guide, please do not hesitate to direct any questions to the General Manager, Paul Moore, or our office staff, myself or other members of the Board of Directors (see contacts in the guide), or, perhaps more expediently on matters of general information, just ask a fellow member. It is important that you thoroughly enjoy being a member of Britannia Yacht Club, so that no matter the main reason for you joining – whether it be sailing, boating, tennis or social activity – the club will be “your cottage in the city” where you can spend many long days of enjoyment, recreation and relaxation. See you at the club. Sincerely, Rob Braden Commodore Britannia Yacht Club [email protected] Krista Kiiffner Director of Membership Britannia Yacht Club [email protected] Britannia Yacht Club New Member’s Guide Table of Contents 1. ABOUT BRITANNIA YACHT CLUB ..................................................... -

Welcome to Byc

WELCOME TO BYC For over 130 years, Britannia Yacht club has provided a quick and easy escape from urban Ottawa into lakeside cottage country that is just fifteen minutes from downtown. Located on the most scenic site in Ottawa at the eastern end of Lac Deschênes, Britannia Yacht Club is the gateway to 45 km of continuous sailing along the Ottawa River. The combination of BYC's recreational facilities and clubhouse services provides all the amenities of lake-side cottage living without having to leave the city. Members of all ages can enjoy sailing, tennis, swimming, childrens' programs and other outdoor activities as well as great opportunities and events for socializing. We have a long history of producing outstanding sailors. Our nationally acclaimed junior sailing program (Learn to Sail) is certified by the Sail Canada (the Canadian Yachting Association) and is structured to nurture skills, self-discipline and personal achievement in a fun environment. BYC has Reciprocal Privileges with other clubs across Canada and the United States so members can enjoy other facilities when they travel. There are a number of different membership categories and mooring rates with flexible payment plans are available. We welcome all new members to our club! Call the office 613-828-5167 or email [email protected] for more information. If you are a new member, please see the Membership Guide; Click Here: https://byc.ca/join See past issues of the club newsletter ~ ‘Full & By’; Click Here: https://byc.ca/members-area/full-by Take a virtual tour of the club house and grounds; Click Here: http://www.byc.ca/images/BYC-HD.mp4 Once again, Welcome to your Cottage in the City!! Britannia Yacht Club, 2777 Cassels Street, Ottawa, ON K2B 6N6 | 613-828-5167 | [email protected] For a great social life we’re the place to be! There’s something for everyone at BYC! Call the office to get on the email list to Fun Events ensure you don’t miss out! In addition, check the; ‘Full&By’ Fitness Newsletter, Website, Facebook, bulletin boards, posters, Tennis and Sailing News Flyers. -

The Full Story of United States V. Smith, Americaâ•Žs Most Important

Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 1 Issue 2 November 2012 The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case Joel H. Samuels Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Political Science Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Rule of Law Commons, Social History Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Joel H. Samuels, The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case, 1 PENN. ST. J.L. & INT'L AFF. 320 (2012). Available at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol1/iss2/7 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2012 VOLUME 1 NO. 2 THE FULL STORY OF UNITED STATES V. SMITH, AMERICA’S MOST IMPORTANT PIRACY CASE Joel H. Samuels* INTRODUCTION Many readers would be surprised to learn that a little- explored nineteenth-century piracy case continues to spawn core arguments in modern-day civil cases for damages ranging from environmental degradation in Latin America to apartheid-era investment in South Africa, as well as criminal trials of foreign terrorists.1 That case, United States v. Smith,2 decided by the United * Associate Professor, Deputy Director, Rule of Law Collaborative, University of South Carolina School of Law. -

BASIC CRUISING STANDARD Course Description This Is One of the Entry Level Courses in the Series of Sail Canada Courses on Sailing Keelboats and on Cruising

Effective Date: March 31, 2017 BASIC CRUISING STANDARD Course Description This is one of the entry level courses in the series of Sail Canada courses on sailing keelboats and on cruising. It develops the student’s ability to take command of and operate (with assistance of competent crew) an auxiliary powered sailing vessel, by day, in light to moderate conditions. Basic boating skills are developed under sail and power with a focus on operation of the vessel as both crew and skipper. Individuals with minimal practical on water experience should consider completing the Start Keelboat Sailing standard before attending for this training. This course introduces the operation of a cruising keelboat both as a powered vessel and as a sailboat. Terminology used in describing the boat and on water activities is taught and used throughout the course. Practical topics under power include simple maneuvering skills as well as departure from and return to dock. Basic sailing skills are developed including sail selection, the use and positioning of sails to provide propulsion, and the operation of the vessel with crew. Required and recommended safety equipment is discussed as is the handling of emergencies that might be encountered while day sailing. The basic rules for avoiding collision with other vessels are explained and this information is applied during the practical sessions. The meaning of weather forecasts is clarified and the impact of weather on vessel operation, crew behavior, and on water activities is discussed. The curriculum includes an elementary introduction to the Canadian navigation system and to the basic use of charts and tide and current tables. -

Tartan 5300 | BLUE WATER SAILING MAGAZINE | CRUISING, SAILING

Tartan 5300 | BLUE WATER SAILING MAGAZINE | CRUISING,... http://bwsailing.com/bw/2010/10/23/tartan-5300/ BLUE WATER SAILING MAGAZINE | CRUISING, SAILING, BOAT REVIEWS, GEAR, CHARTERING | 888.800.SAIL Posted on October 23, 2010 by Blue Water Sailing TARTAN 5300 • I have to admit that I have a soft spot for Tartans. In 1963 or so, my parents and our neighbors in partnership bought an early Tartan 27—the classic S&S design that launched the company. For years, we cruised and raced the boat all over the Northeast as a family of five and thought nothing of staying aboard for a week at a time. When my folks decided to move up in size, they sold the boat to another neighbor, who kept it for 30 years and cruised it all over New England. When he decided to sell, who should step up to buy the then-40-year-old boat but my nephew, who keeps it near Boston and sails it whenever he can…now with a new engine and new sails, but still the same 47-year-old cruiser. So the boat is still in the family.That says a lot about Tartan’s place in the American sailing scene. The boat building company, founded by Ohio native Charlie Britton in 1960, has always been focused primarily on solid, honest boats that appeal to families, whether they are cruising in a Tartan 37 or beating around the buoys in a Tartan Ten. While times change and designs evolve, that fundamental Tartan quality remains the same.In July, I had the chance to test sail the center-cockpit Tartan 5300 Luora, which belongs to Jeff and Linda Lennox. -

1 U.S. Statutes Relating to Piracy 18 U.S.C. § 2280. Violence Against

U.S. Statutes Relating to Piracy 18 U.S.C. § 2280. Violence against maritime navigation (a) Offenses.-- (1) In general.--A person who unlawfully and intentionally-- (A) seizes or exercises control over a ship by force or threat thereof or any other form of intimidation; (B) performs an act of violence against a person on board a ship if that act is likely to endanger the safe navigation of that ship; (C) destroys a ship or causes damage to a ship or to its cargo which is likely to endanger the safe navigation of that ship; (D) places or causes to be placed on a ship, by any means whatsoever, a device or substance which is likely to destroy that ship, or cause damage to that ship or its cargo which endangers or is likely to endanger the safe navigation of that ship; (E) destroys or seriously damages maritime navigational facilities or seriously interferes with their operation, if such act is likely to endanger the safe navigation of a ship; (F) communicates information, knowing the information to be false and under circumstances in which such information may reasonably be believed, thereby endangering the safe navigation of a ship; (G) injures or kills any person in connection with the commission or the attempted commission of any of the offenses set forth in subparagraphs (A) through (F); or (H) attempts or conspires to do any act prohibited under subparagraphs (A) through (G), shall be fined under this title, imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both; and if the death of any person results from conduct prohibited by this paragraph, shall be punished by death or imprisoned for any term of years or for life. -

The Bluewater 400 Is Probably the Best Cruising Yacht Ever Built In

Footloose II BLUEWATER 420 The Bluewater 420 is probably one of the best cruising yachts ever built in Australia, with world class construction and fitout. Footloose II is in excellent condition with an impressive inventory, and is ready to sail anywhere. Footloose II is an exceptional Bluewater built for an experienced pilot who believed in strength and seaworthiness of construction as well backup systems in a yacht that could take him anywhere in the world. This is a yacht that has been maintained fastidiously and would represent an exceptional buy. KEY FEATURES Designer: Joe Adams Construction: Solid GRP with integral keel and skeg, built to survey standards Dimensions: LOA 41’10” (12.75m) LWL 35’ (10.67m) Beam 13’1” (4m) Draft 6’3” (1.9m) Disp app 12,170 kgs (Lightship) Registration OF341Q (QLD) ON856343 (AUS) Ship No Yacht type: Sloop rigged cutter with furling headsail. Launched 1999 Layout: 2 cabins: owner’s queen size berth aft with ensuite, 1 forward cabin with double V-berth forward with vanity unit. Sails: Main. Headsail. Staysail. Storm Staysail. Storm Trysail. MPS cruising spinnaker. Engine: Nanni Diesel 1523584E. 5010 hrs. Fuel capacity: Approx 580 litres. Range 1700 NM @ 2LPH @ 6K. Water capacity: Approx 900 litres. Holding tank capacity: Approx 325 litres grey water. 260 litres black water. 2 tanks. Power: 12V & 240V – all deep cycle batteries. Batteries (house 4, electronics x2, engine x1). Exceptional house-power supported by 2x 60w solar panels. Total 660 AH, plus engine start battery 700 CCA. 1 Air Marine 400w wind generator. Portable Honda Genset 2KVA. Heart Inverter Freedom 20 2KVA. -

Redalyc.Cruise Passengers' Perceptions of Safety and Security

Rosa dos Ventos E-ISSN: 2178-9061 [email protected] Universidade de Caxias do Sul Brasil Baker, David Cruise passengers’ perceptions of safety and security while Cruising the Western Caribbean. Rosa dos Ventos, vol. 5, núm. 1, enero-marzo, 2013, pp. 140-154 Universidade de Caxias do Sul Caxias do Sul, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=473547092012 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Rosa dos Ventos SPECIAL ISSUE – The Dialectics of Borders Empires and Limens 5(I) 140-154, jan-mar, 2013 © O(s) Autor(es) 2013 ISSN: 2178-9061 Cruise passengers’ Associada ao: Programa de Mestrado em Turismo Hospedada em: perceptions of safety and http://ucs.br/revistarosadosventos security while Cruising the Western Caribbean. David Baker1 ABSTRACT Each year millions of people vacation aboard cruise ships, some carrying thousands of passengers and crew members. These ships are small, floating cities that offer many options for food and entertainment. However, just as in life ashore, passengers can be exposed to dangerous situations involving their safety and security. Despite lots of bad publicity about the cruise industry especially after the Costa Concordia disaster, the results of this study indicated that Key words: Cruise ship. Cruise cruise passengers were not overly concerned about their safety and passengers. Perceptions. Safety. security while on a cruise. Cruise ship operators have the obligation Security. -

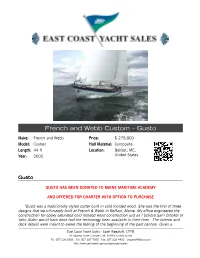

French and Webb Custom – Gusto

French and Webb Custom – Gusto Make: French and Webb Price: $ 275,000 Model: Custom Hull Material: Composite Length: 44 ft Location: Belfast, ME, Year: 2002 United States Gusto GUSTO HAS BEEN DONATED TO MAINE MARITIME ACADEMY AND OFFERED FOR CHARTER WITH OPTION TO PURCHASE "Gusto was a traditionally styled cutter built in cold molded wood. She was the first of three designs that we ultimately built at French & Webb in Belfast, Maine. My office engineered the construction for epoxy saturated cold molded wood construction just as I believe Sam Crocker or John Alden would have done had the technology been available in their time. The interior and deck details were meant to evoke the feeling of the beginning of the past century. Given a East Coast Yacht Sales - Scott Woodruff, CPYB 44 Bayview Street, Camden, ME 04843, United States Tel: 207-236-8656 Tel: 207-387-7205 Fax: 207-236-4402 [email protected] http://www.yachtworld.com/eastcoastyachtsales reasonable amount of maintenance by the owner, I'm pretty sure cold molded yachts will outlast all other methods of construction." Chuck Paine from My Yacht Designs and The Lessons They Taught Me There is reason that Chuck Paine and Charles Doane sing from the rooftops about this yacht, the design qualities, artisan builders and the sailing characteristics of this yacht... because this yacht is kind of vessel that yachties dream about. Exceptionally well built to the exacting standards of a world class designer Gusto has a level of pedigree that is rarely seen in the modern cruising yacht. Designed to sail, built to last and maintained out of love, Gusto is no less than just spectacular. -

Launching 2021 1 | X-Yachts X56

LAUNCHING 2021 1 | X-YACHTS X56 THE X56 IS THE FIRST OF TWO ALL NEW 50 FOOT+ MODELS THAT WILL TAKE THE PURE X RANGE TO A WHOLE NEW LEVEL, BLENDING LUXURY AND STYLE WITH PERFORMANCE AND CRUISING CAPABILITY. FIND OUT MORE AT X-YACHTS.COM These descriptions, illustrations and dimensions are preliminary and not contractual binding. 5 | X-YACHTS X56 SUPERIOR SAILING PLEASURE The X56 is a fifty-six-foot performance cruising yacht designed with serious cruising in mind; be that crossing the Atlantic, or exploring beautiful Mediterranean islands. The X56 joins the hugely successful and critically acclaimed Pure X Range. The design philosophy was very clear from the outset - like all our yachts, we place a huge emphasis on giving the owner a superb and comfortable sailing experience, on a yacht that is easy to handle by all the crew. These descriptions, illustrations and dimensions are preliminary and not contractual binding. FIND OUT MORE AT X-YACHTS.COM X-YACHTS X56 | 8 YOU’RE IN COMMAND Experience the feeling of confidence and control with the X56. The helm position offers excellent visibility and agile handling that puts you in control. The modern outboard mounted pedestals free up deck space, maintaining a clean area, free of hazards. The X56 has various wheel options to select from. Configure your own X56 on x-yachts. com. These descriptions, illustrations and dimensions are preliminary and not contractual binding. FIND OUT MORE AT X-YACHTS.COM 9 | X-YACHTS X56 FLEXIBLE SAILPLAN It could be argued that the sailplan for any yacht is one of its most import- ant features. -

Glossary of Terms for Cruising and Cruise

GLOSSARY OF TERMS FOR CRUISING AND CRUISE PLANNING USPS Marine Environment Committee TERM / WORD = DEFINITION / EXPLANATION AIS = Automatic Indentification System (transponders / receivers) ‐ An automatic tracking system used by vessels for exchanging identifying information. Anchor = A heavy metal device fastened to a chain or line to hold a vessel in position, partly because of its weight but chiefly because the design shape digs into the bottom. Parts consist of: Flute, Shank, Crown, Ring, etc. (see Appendix C) Anchor set and hold = How easily an anchor will properly orient itself to penetrate the bottom and how much effort it will take to break the anchor free. Bare Boat = A type of chartering in which the person chartering a boat assumes responsibility and provides their own crew. Barometer = An instrument for measuring atmospheric pressure. Beam = The width of a boat from gunwale to gunwale at the widest point. Biocide = A chemical substance or microorganism which can deter, render harmless, or exert a controlling effect on any harmful organism. Biocides can be added to other materials (such as diesel fuel) to protect them against biological infestation and growth. Boat Survey = An inspection of a boat by a marine surveyor for insurance purposes or prior to the purchase of the boat. 1 Boom Vang = A system of fittings to hold the boom down under some sailing conditions. Bosun Chair = A chair used to hoist a crew member to the top of a mast or rigging, usually for making repairs. Broker Firm = A company which will help you find a suitable boat to charter. Bulwarks = The extension of the ship’s side above the main deck or walkway fore and aft to protect it against heavy weather.