The Bacterial Zoonoses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Combined Effect of Sulfanilamide and Penicillin in Treatment Of

THE COMBINED EFFECT OF STJLFANILAMIDE AND PENICILLIN IN TREATMENT OF EXPERIMENTAL ERYSIPELOTHRIX RHUSIOPATHIAE INFECTION OF MICE* JOSEPH V. KLAUDER, M.D. AND ANNA M. RULE In a previous communication (1) we reported the results of determinations oi the therapeutic effect of sulfonamide compounds in mice inoculated with Er- ysipelothrix rhusiopathiae. A report was also made of the ineffective use of these compounds in treatment of patients with erysipeloid of Rosenbach and in treatment of one patient with the septicemic form of the infection (2). In our experimental study sulfanilamide, sulfapyridine, sulfathiazole and sul- fadiazine were separately administered to mice orally in doses of 0.2 Gm. per kilogram of body weight. To some the compounds were administered twice daily for two days before inoculation with a virulent strain of Erysipelothrix rhu- siopathiae and twice daily thereafter for six additional days. For others treat- ment was begun four hours after inoculation and then administered twice daily for six additional days; in still others, for eight additional days. It was observed that 12.5 per cent of mice treated before or after the admin- istration of these compounds survived. Additional evidence of some therapeutic effect was the greater percentage (50 per cent) of survival of the animals treated before inoculation and the longer time of survival of animals treated after inocu- lation compared with those of the untreated control group. The therapeutic effect of these compounds is therefore limited. Sulfanilamide and sulfapyridine appeared to give better results than sulfathiazole and sulfadiazine. The thera- peutic effect of these compounds was slightly enhanced when they were employed in conjunction with subcurative injections of immune serum. -

Fournier's Gangrene Caused by Listeria Monocytogenes As

CASE REPORT Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes as the primary organism Sayaka Asahata MD1, Yuji Hirai MD PhD1, Yusuke Ainoda MD PhD1, Takahiro Fujita MD1, Yumiko Okada DVM PhD2, Ken Kikuchi MD PhD1 S Asahata, Y Hirai, Y Ainoda, T Fujita, Y Okada, K Kikuchi. Une gangrène de Fournier causée par le Listeria Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes as the monocytogenes comme organisme primaire primary organism. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2015;26(1):44-46. Un homme de 70 ans ayant des antécédents de cancer de la langue s’est présenté avec une gangrène de Fournier causée par un Listeria A 70-year-old man with a history of tongue cancer presented with monocytogenes de sérotype 4b. Le débridement chirurgical a révélé un Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b. adénocarcinome rectal non diagnostiqué. Le patient n’avait pas Surgical debridement revealed undiagnosed rectal adenocarcinoma. d’antécédents alimentaires ou de voyage apparents, mais a déclaré The patient did not have an apparent dietary or travel history but consommer des sashimis (poisson cru) tous les jours. reported daily consumption of sashimi (raw fish). L’âge avancé et l’immunodéficience causée par l’adénocarcinome rec- Old age and immunodeficiency due to rectal adenocarcinoma may tal ont peut-être favorisé l’invasion directe du L monocytogenes par la have supported the direct invasion of L monocytogenes from the tumeur. Il s’agit du premier cas déclaré de gangrène de Fournier tumour. The present article describes the first reported case of attribuable au L monocytogenes. Les auteurs proposent d’inclure la con- Fournier’s gangrene caused by L monocytogenes. -

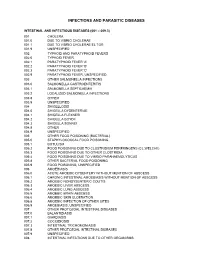

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis Are Tick-Borne Diseases Caused by Obligate Anaplasmosis: Intracellular Bacteria in the Genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma

Ehrlichiosis and Importance Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tick-borne diseases caused by obligate Anaplasmosis: intracellular bacteria in the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These organisms are widespread in nature; the reservoir hosts include numerous wild animals, as well as Zoonotic Species some domesticated species. For many years, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species have been known to cause illness in pets and livestock. The consequences of exposure vary Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, from asymptomatic infections to severe, potentially fatal illness. Some organisms Canine Hemorrhagic Fever, have also been recognized as human pathogens since the 1980s and 1990s. Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, Etiology Tracker Dog Disease, Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are caused by members of the genera Ehrlichia Canine Tick Typhus, and Anaplasma, respectively. Both genera contain small, pleomorphic, Gram negative, Nairobi Bleeding Disorder, obligate intracellular organisms, and belong to the family Anaplasmataceae, order Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsiales. They are classified as α-proteobacteria. A number of Ehrlichia and Canine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Anaplasma species affect animals. A limited number of these organisms have also Equine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, been identified in people. Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Recent changes in taxonomy can make the nomenclature of the Anaplasmataceae Tick-borne Fever, and their diseases somewhat confusing. At one time, ehrlichiosis was a group of Pasture Fever, diseases caused by organisms that mostly replicated in membrane-bound cytoplasmic Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, vacuoles of leukocytes, and belonged to the genus Ehrlichia, tribe Ehrlichieae and Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, family Rickettsiaceae. The names of the diseases were often based on the host Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, species, together with type of leukocyte most often infected. -

Establishment of Listeria Monocytogenes in the Gastrointestinal Tract

microorganisms Review Establishment of Listeria monocytogenes in the Gastrointestinal Tract Morgan L. Davis 1, Steven C. Ricke 1 and Janet R. Donaldson 2,* 1 Center for Food Safety, Department of Food Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72704, USA; [email protected] (M.L.D.); [email protected] (S.C.R.) 2 Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, The University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS 39406, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-601-266-6795 Received: 5 February 2019; Accepted: 5 March 2019; Published: 10 March 2019 Abstract: Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram positive foodborne pathogen that can colonize the gastrointestinal tract of a number of hosts, including humans. These environments contain numerous stressors such as bile, low oxygen and acidic pH, which may impact the level of colonization and persistence of this organism within the GI tract. The ability of L. monocytogenes to establish infections and colonize the gastrointestinal tract is directly related to its ability to overcome these stressors, which is mediated by the efficient expression of several stress response mechanisms during its passage. This review will focus upon how and when this occurs and how this impacts the outcome of foodborne disease. Keywords: bile; Listeria; oxygen availability; pathogenic potential; gastrointestinal tract 1. Introduction Foodborne pathogens account for nearly 6.5 to 33 million illnesses and 9000 deaths each year in the United States [1]. There are over 40 pathogens that can cause foodborne disease. The six most common foodborne pathogens are Salmonella, Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Clostridium perfringens. -

Listeriosis (“Circling Disease”) Extended Version

Zuku Review FlashNotesTM Listeriosis (“circling disease”) Extended Version Classic case: Silage-fed adult cow, head tilt, circling, asymmetric sensation loss on face Presentation: Signalment and History Adult cattle, sheep, goats, (possibly camelids) . Indoors in winter with feeding of silage . Extremely rare in horses Poultry and pet birds Human listeria outbreaks Clinical signs (mammals) Head tilt Circling Dullness Sensory and motor dysfunction of trigeminal nerve . Asymmetric sensory loss on face . Weak jaw closure Purulent ophthalmitis Exposure keratitis Isolation from rest of herd Ocular and nasal discharge Listeriosis in a Holstein. Food remaining in mouth Note the head tilt and drooped ear Bloat Marked somnolence Tetraparesis, ataxia Poor to absent palpebral reflexes Difficulty swallowing/poor gag reflex Tongue paresis Obtundation, semicoma, death Clinical signs (avian listeriosis) Often subclinical Older birds and poultry (septicemia) . Depression, lethargy . Sudden death Younger birds and poultry (chronic form) . Torticollis . Paresis/paralysis DDX: Listeriosis in an ataxic goat Mammals Brainstem abscess, basilar empyema, otitis media/interna, Maedi-Visna, rabies, caprine arthritis-encephalitis, Parelaphostrongylus tenuis, scrapie Avian Colibacillosis, pasteurellosis, erysipelas, velogenic viscerotropic Newcastle disease 1 Zuku Review FlashNotesTM Listeriosis (“circling disease”) Extended Version Test(s) of choice: Mammals-Clinical signs and Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis . Mononuclear pleocytosis, -

| Oa Tai Ei Rama Telut Literatur

|OA TAI EI US009750245B2RAMA TELUT LITERATUR (12 ) United States Patent ( 10 ) Patent No. : US 9 ,750 ,245 B2 Lemire et al. ( 45 ) Date of Patent : Sep . 5 , 2017 ( 54 ) TOPICAL USE OF AN ANTIMICROBIAL 2003 /0225003 A1 * 12 / 2003 Ninkov . .. .. 514 / 23 FORMULATION 2009 /0258098 A 10 /2009 Rolling et al. 2009 /0269394 Al 10 /2009 Baker, Jr . et al . 2010 / 0034907 A1 * 2 / 2010 Daigle et al. 424 / 736 (71 ) Applicant : Laboratoire M2, Sherbrooke (CA ) 2010 /0137451 A1 * 6 / 2010 DeMarco et al. .. .. .. 514 / 705 2010 /0272818 Al 10 /2010 Franklin et al . (72 ) Inventors : Gaetan Lemire , Sherbrooke (CA ) ; 2011 / 0206790 AL 8 / 2011 Weiss Ulysse Desranleau Dandurand , 2011 /0223114 AL 9 / 2011 Chakrabortty et al . Sherbrooke (CA ) ; Sylvain Quessy , 2013 /0034618 A1 * 2 / 2013 Swenholt . .. .. 424 /665 Ste - Anne -de - Sorel (CA ) ; Ann Letellier , Massueville (CA ) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS ( 73 ) Assignee : LABORATOIRE M2, Sherbrooke, AU 2009235913 10 /2009 CA 2567333 12 / 2005 Quebec (CA ) EP 1178736 * 2 / 2004 A23K 1 / 16 WO WO0069277 11 /2000 ( * ) Notice : Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this WO WO 2009132343 10 / 2009 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 WO WO 2010010320 1 / 2010 U . S . C . 154 ( b ) by 37 days . (21 ) Appl. No. : 13 /790 ,911 OTHER PUBLICATIONS Definition of “ Subject ,” Oxford Dictionary - American English , (22 ) Filed : Mar. 8 , 2013 Accessed Dec . 6 , 2013 , pp . 1 - 2 . * Inouye et al , “ Combined Effect of Heat , Essential Oils and Salt on (65 ) Prior Publication Data the Fungicidal Activity against Trichophyton mentagrophytes in US 2014 /0256826 A1 Sep . 11, 2014 Foot Bath ,” Jpn . -

COI Estimates of Listeriosis

COI Estimates of Listeriosis women, newborn/fetal cases, and other adults (i.e., adults who are not pregnant women)(Roberts and Listeriosis is the disease caused by the infectious bac- Pinner 1990). Listeriosis in pregnant women is usual- terium, Listeria monocytogenes. Listeriosis may have ly relatively mild and may be manifested as a flu-like a bimodal distribution of severity with most cases syndrome or placental infection. They are hospital- being either mild or severe (CAST 1994, p. 51). ized for observation. Because of data limitations, the Milder cases of listeriosis are characterized by a sud- less severe cases are not considered here. den onset of fever, severe headache, vomiting, and other influenza-type symptoms. Reported cases of lis- Infected pregnant women can transmit the disease to teriosis are often manifested as septicemia and/or their newborns/fetuses either before or during deliv- meningoencephalitis and may also involve delirium ery. Infected newborns/fetuses may be stillborn, and coma (Benenson 1990, p. 250). Listeriosis may develop meningitis (inflammation of the tissue sur- cause premature death in fetuses, newborns, and some rounding the brain and/or spinal cord) in the neonatal adults or cause developmental complications for fetus- period, or are born with septicemia (syndrome of es and newborns. decreased blood pressure and capillary leakage) (Benenson 1990, p. 250).74 Septicemia and meningi- Listeria can grow at refrigeration temperatures (CAST tis can both be serious and life-threatening. A portion 1994, p. 32; Pinner et al. 1992, p. 2049). There is no of babies with meningitis will go on to develop chron- consensus as to the infectious dose of Listeria, though ic neurological complications. -

Listeria Monocytogenes in Fresh Fruits and Vegetables Master's

Listeria monocytogenes in Fresh Fruits and Vegetables Master’s degree in Agriculture and Life Science By Alicia L. Thomas Introduction Approximately 1600 illnesses and 260 deaths in the United States are caused by food contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes (CDC, 2014; Scallan, et al, 2011). Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive bacterium (Vaquez- Boland, Kuhn et al, 2011) that causes the infection listeriosis within the body. L. monocytogenes can be found in ready to eat (RTE) foods. Unlike other foodborne pathogens, one of the organisms unique characteristics is that it is a psychrotroph, meaning it can grow in refrigeration temperatures; therefore, refrigeration is not the most effective way to control the pathogens growth (figure 1) (Frazer, 1998), even when temperatures almost reach freezing. Figure 1. Temperature growth ranges for select foodborne pathogens Microorganism Growth Range (oF) Salmonella sp 41.4oF – 115.2oF Clostridium botulinum A&B 50.0oF – 118.4oF Clostridium botulinum Non-proteolytic B 37.9oF – 113.0oF Clostridium botulinum E 37.9oF – 113.0oF Clostridium botulinum F 37.9oF – 113.0oF Staphylococcus aureus 44.6oF – 122.0oF Yersinia enterocolytica 29.7oF – 107.6oF Listeria monocytogenes 31.3oF – 113.0oF Vibrio cholerae 01 50.0oF – 109.4oF Vibrio parahaemolyticus 41.0oF – 111.0oF Clostridium perfringens 50.0oF – 125.6oF Bacillus cereus 39.2oF – 131.0oF Escherichia coli (pathogenic types) 44.6oF – 120.9oF Shigella spp. 43.0oF – 116.8oF Frazer, A. M., 1998: Control by Refrigeration and Freezing The infection listeriosis, can affect people of all ages, but predominantly present in those with weakened immune systems such as pregnant women, newborns and those who are elderly (CDC, 2014). -

Investigation of Swabs from Skin and Superficial Soft Tissue Infections

UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations Investigation of swabs from skin and superficial soft tissue infections Issued by the Standards Unit, Microbiology Services, PHE Bacteriology | B 11 | Issue no: 6.5 | Issue date: 19.12.18 | Page: 1 of 37 © Crown copyright 2018 Investigation of swabs from skin and superficial soft tissue infections Acknowledgments UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations (SMIs) are developed under the auspices of Public Health England (PHE) working in partnership with the National Health Service (NHS), Public Health Wales and with the professional organisations whose logos are displayed below and listed on the website https://www.gov.uk/uk- standards-for-microbiology-investigations-smi-quality-and-consistency-in-clinical- laboratories. SMIs are developed, reviewed and revised by various working groups which are overseen by a steering committee (see https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/standards-for-microbiology-investigations- steering-committee). The contributions of many individuals in clinical, specialist and reference laboratories who have provided information and comments during the development of this document are acknowledged. We are grateful to the medical editors for editing the medical content. For further information please contact us at: Standards Unit Microbiology Services Public Health England 61 Colindale Avenue London NW9 5EQ E-mail: [email protected] Website: https://www.gov.uk/uk-standards-for-microbiology-investigations-smi-quality- and-consistency-in-clinical-laboratories PHE publications gateway number: 2016056 UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations are produced in association with: Logos correct at time of publishing. Bacteriology | B 11 | Issue no: 6.5 | Issue date: 19.12.18 | Page: 2 of 37 UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations | Issued by the Standards Unit, Public Health England Investigation of swabs from skin and superficial soft tissue infections Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................ -

Differential Diagnosis Between Streptococcus Agalactiae and Listeria Monocytogenes in the Clinical Laboratory

ANNALS OF CLINICAL AND LABORATORY SCIENCE, Vol. 7, No. 3 Copyright © 1977, Institute for Clinical Science Differential Diagnosis between Streptococcus Agalactiae and Listeria Monocytogenes in the Clinical Laboratory CHRISTINE KONTNICK, M.T., ALEXANDER von GRAEVENITZ, M.D., and VINCENT PISCITELLI, M.T. Clinical Microbiology Laboratories, Yale-New Haven Hospital, and Department of Laboratory Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06504 ABSTRACT Streptococci of the group B (S. agalactiae) and Listeria monocytogenes resemble each other in many morphological and biochemical characteris tics. Ten beta-hemolytic strains of each species were subjected to 26 tests commonly and easily performed in the clinical laboratory. Macroscopic and microscopic morphology on solid media showed differences only in the size of the colonies and in the length of the individual organisms. Among many other tests, hippurate hydrolysis and the CAMP reaction were pos itive in both species. In the presence of these two reactions, a negative catalase test and chaining in broth would make a presumptive diagnosis of S. agalactiae, while motility at 25 C, the presence of the Henry effect, and resistance to furadantin would be indicative of L. monocytogenes. Introduction in Gram-stained smears; (3) a negative bacitracin test and (4) a positive test for The high incidence of Streptococcus either (a) hippurate hydrolysis, (b) the agalactiae (group B) in human speci CAMP reaction or (c) the formation of an mens, which has been recognized only in orange-red pigment. However, if one of the past decade, calls for a rapid pre these conditions for the diagnosis is not sumptive diagnosis of the species.