Other Traditional Durum-Derived Products

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MOROCCAN SOUP Harira Bowl (Vegan) : Traditional Moroccan Soup with Tomato, Lentils, Chick Peas, Onion, $6 Cilantro, Parsley, Ginger, Saffron, Rice

MOROCCAN RESTAURANT 3191 S. Grand Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63118 www.baidarestaurant.com 314.932.7950 APPETIZERS Shrimp Pil Pil : Sauteed Shrimp in a $13 Bastilla : Sweet and savory chicken pie, $14 fresh house-made tomato sauce with layered with tender spiced chicken, eggs, fennel and garlic sauce. Served with flat cilantro, parsley, almonds, and honey, bread dusted with cinnamon, and powdered sugar M’Lwee Chicken : A flaky layered $7 pastry stuffed with onions, cumin, Zaaluk (Vegan) : Fresh eggplant and $6 coriander, herbs, chicken and other spices tomato blended with olive oil, cilantro, then pan fried. Served with Harissa parsley, garlic, cumin, harissa and lemon juice. Served with Pita Bread Shakshuka (Vegan) : Sweet and spicy $6 tomato sauce with roasted red pepper, Loubia (Vegan) : Traditional slow baked $6 garlic, herbs and spiced with traditional white beans with paprika, cumin, cilantro, Moroccan flavor. Served with flat bread parsley, and chopped tomato. Served with One Egg on Top $1 flat bread Salads are in the Vegetarian and Vegan Section MOROCCAN SOUP Harira Bowl (Vegan) : Traditional Moroccan soup with tomato, lentils, chick peas, onion, $6 cilantro, parsley, ginger, saffron, rice THE MOROCCAN CUISINE This cuisine Is a very diverse cuisine because of 7 Vegetables served in the couscous : Zucchini, Morocco’s interactions with other nations over yellow squash, garbanzo, butternut squash, lima the centuries: Imazighen or the Berbers, the beans, carrots, green peas first settlers of Morocco (in Arabic Al Maghreeb Spices : lot of Spices are used: Karfa (cinnamon), which means the land of the sunset), Phoenicians, Kamun (cumin), Kharkum (turmeric), Skinjbeer Romans, Arabs, Africans and Moors (who fled (ginger), Leebzar (pepper), Tahmira (paprika), from Spain). -

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet a Family Resource from the Celiac Disease Program

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet A family resource from the Celiac Disease Program celiacdisease.stanfordchildrens.org What Is a Gluten-Free How Do I Diet? Get Started? A gluten-free diet is a diet that completely Your first instinct may be to stop at the excludes the protein gluten. Gluten is grocery store on your way home from made up of gliadin and glutelin which is the doctor’s office and search for all the found in grains including wheat, barley, gluten-free products you can find. While and rye. Gluten is found in any food or this initial fear may feel a bit overwhelming product made from these grains. These but the good news is you most likely gluten-containing grains are also frequently already have some gluten-free foods in used as fillers and flavoring agents and your pantry. are added to many processed foods, so it is critical to read the ingredient list on all food labels. Manufacturers often Use this guide to select appropriate meals change the ingredients in processed and snacks. Prepare your own gluten-free foods, so be sure to check the ingredient foods and stock your pantry. Many of your list every time you purchase a product. favorite brands may already be gluten-free. The FDA announced on August 2, 2013, that if a product bears the label “gluten-free,” the food must contain less than 20 ppm gluten, as well as meet other criteria. *The rule also applies to products labeled “no gluten,” “free of gluten,” and “without gluten.” The labeling of food products as “gluten- free” is a voluntary action for manufacturers. -

Italia Italia

Italia 22018018 Group travel to Italy since 1985 since Dear Partner, There's always a good reason to celebrate in Italy! 2018 is approaching and it will bring important events, such as: The opening of „FICO Eataly World“ in Bologna, which is an impressive investment into the Italian food excellence to be visited and tasted! Palermo, the Italian capital of culture The 150th anniversary of the death of Gioacchino Rossini The "Salone del Gusto" in Turin, the best of Italian food and wine exhibition (September 2018) Altar servers meeting in Rome - August 2018 ...and last but not least, the opening of the most technological and emotional show in Europe, the Universal Judgement, starting on 15th March 2018 in Rome. In addition to that, we are already preparing for the events of 2019, two of them: Matera, the European Capital of culture 2019 500 years since the death of Leonardo da Vinci However, the activity we prefer most is developing "tailormade" programmes for our clients' events and we pay particular attention to make them unique! Have a look our 2018 Gadis catalogue for numerous examples of activities that can be adapted to your needs and wishes. So, don't forget..... there's plenty of reasons to celebrate in Italy! Your Gadis Team Claudio Scalambrin Ower and managing director 2 | Tel +39 0183 548 1 - Fax: +39 0183 548 222 - [email protected] Index Lombardia, Lago Maggiore Team [email protected] Piemonte, Lucia Who is taking care +39 0183 548 413 Liguria & Côte d’Azur of your groups Noemi [email protected] +39 0183 548 412 Marta Pag. -

Quels Sont Les Repas Du Ramadan

Bien gérer son alimentation durant le Ramadan Qu’est-ce que le Ramadan ? Le Ramadan correspond à une période sacrée, dans la religion musulmane, pendant laquelle le rythme et les habitudes changent. Les personnes qui le suivant doivent s’abstenir de manger et de boire du lever au coucher du soleil. C’est aussi une période où l’on prend souvent plus de temps pour cuisiner (plats, bricks, pâtisseries, pains, beignets…). Cela implique donc un bouleversement de l’alimentation quotidienne. Quels sont les repas du ramadan ? Les repas pendant le ramadan sont au nombre de trois et s’appellent différemment selon le moment de la journée où ils sont pris : « Al Ftour » à la rupture du jeûne après le coucher du soleil, « Al Ichaa » quelques heures après Al Ftour, « S’Hour » avant le lever du soleil. Certaines années, la rupture du jeûne se fait à une heure tardive. De nombreuses personnes ne prennent donc pas de second repas par manque d’appétit. Comment m’alimenter pendant le ramadan ? L’idéal est de ne pas grignoter tout au long de la soirée et de prendre trois repas réguliers. Cela signifie un petit déjeuner pris très tôt, un déjeuner (à la rupture du jeûne) et un dîner (dans la nuit). Si vous avez du mal à maintenir 3 repas essayez d’en faire 2 au minimum (un petit déjeuner et un repas au coucher du soleil). Pour éviter tout risque de carence, diversifiez votre alimentation en associant les différents groupes alimentaires : - féculents : pâtes, riz, lentilles, pois chiches, orge, pain, pommes de terre, semoule…Ils sont la source d’énergie de votre corps, ils sont essentiels pour éviter d’avoir faim ou d’être fatigué dans la journée. -

Festiwal Chlebów Świata, 21-23. Marca 2014 Roku

FESTIWAL CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA, 21-23. MARCA 2014 ROKU Stowarzyszenie Polskich Mediów, Warszawska Izba Turystyki wraz z Zespołem Szkół nr 11 im. Władysława Grabskiego w Warszawie realizuje projekt FESTIWAL CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA 21 - 23 marca 2014 r. Celem tej inicjatywy jest promocja chleba, pokazania jego powszechności, ale i równocześnie różnorodności. Zaplanowaliśmy, że będzie się ona składała się z dwóch segmentów: pierwszy to prezentacja wypieków pieczywa według receptur kultywowanych w różnych częściach świata, drugi to ekspozycja producentów pieczywa oraz związanych z piekarnictwem produktów. Do udziału w żywej prezentacji chlebów świata zaprosiliśmy: Casa Artusi (Dom Ojca Kuchni Włoskiej) z prezentacją piady, producenci pity, macy oraz opłatka wigilijnego, Muzeum Żywego Piernika w Toruniu, Muzeum Rolnictwa w Ciechanowcu z wypiekiem chleba na zakwasie, przedstawiciele ambasad ze wszystkich kontynentów z pokazem własnej tradycji wypieku chleba. Dodatkowym atutem będzie prezentacja chleba astronautów wraz osobistym świadectwem Polskiego Kosmonauty Mirosława Hermaszewskiego. Nie zabraknie też pokazu rodzajów ziarna oraz mąki. Realizacją projektu będzie bezprecedensowa ekspozycja chlebów świata, pozwalająca poznać nie tylko dzieje chleba, ale też wszelkie jego odmiany występujące w różnych regionach świata. Taka prezentacja to podkreślenie uniwersalnego charakteru chleba jako pożywienia, który w znanej czy nieznanej nam dotychczas innej formie można znaleźć w każdym zakątku kuli ziemskiej zamieszkałym przez ludzi. Odkąd istnieje pismo, wzmiankowano na temat chleba, toteż, dodatkowo, jego kultowa i kulturowo – symboliczna wartość jest nie do przecenienia. Inauguracja FESTIWALU CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA planowana jest w piątek, w dniu 21 marca 2014 roku, pierwszym dniu wiosny a potrwa ona do niedzieli tj. do 23.03. 2014 r.. Uczniowie wówczas szukają pomysłów na nieodbywanie typowych zajęć lekcyjnych. My proponujemy bardzo celowe „vagari”- zapraszając uczniów wszystkich typów i poziomów szkoły z opiekunami do spotkania się na Festiwalu. -

An Organic Khorasan Wheat-Based Replacement Diet Improves Risk Profile of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: a Randomized Crossover Trial

Nutrients 2015, 7, 3401-3415; doi:10.3390/nu7053401 OPEN ACCESS nutrients ISSN 2072-6643 www.mdpi.com/journal/nutrients Article An Organic Khorasan Wheat-Based Replacement Diet Improves Risk Profile of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Randomized Crossover Trial Anne Whittaker 1, Francesco Sofi 2,3,4,*, Maria Luisa Eliana Luisi 4, Elena Rafanelli 4, Claudia Fiorillo 5, Matteo Becatti 5, Rosanna Abbate 3, Alessandro Casini 2, Gian Franco Gensini 3 and Stefano Benedettelli 1 1 Department of Agrifood Production and Environmental Sciences, University of Florence, Piazzale delle Cascine 18, 50144 Florence, Italy; E-Mails: [email protected] (A.W.); [email protected] (S.B.) 2 Unit of Clinical Nutrition, Careggi University Hospital, Largo Brambilla 3, 50134 Florence, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Largo Brambilla 3, 50134, Florence, Italy; E-Mails: [email protected] (R.A.); [email protected] (G.F.G.) 4 Don Carlo Gnocchi Foundation Florence, Via di Scandicci 269, 50143, Florence, Italy; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.L.L.); [email protected] (E.R.) 5 Department of Clinical and Experimental Biomedical Sciences, Interdipartimental Center for Research on Food and Nutrition, University of Florence, Sesto Fiorentino, Florence, 50019, Italy; E-Mails: [email protected] (C.F.); [email protected] (M.B.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-055-7949420; Fax: +39-055-7949418. Received: 20 November 2014 / Accepted: 21 April 2015 / Published: 11 May 2015 Abstract: Khorasan wheat is an ancient grain with previously reported health benefits in clinically healthy subjects. -

Les Bases De Données Lexicographiques Panfrancophones : Algérie Et Maroc Étude Comparative

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DÉMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTÈRE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE Université El Hadj Lakhdar – Batna Faculté des Lettres et des Langues École Doctorale de Français Thème Les Bases de Données Lexicographiques Panfrancophones : Algérie et Maroc Étude comparative Mémoire élaboré en vue de l'obtention du diplôme de Magistère Option : Sciences du langage Sous la direction de : Présenté et soutenu par : Pr. Gaouaou MANAA M. Samir CHELLOUAI Membres du jury : Président : M. Samir ABDELHAMID Pr. Université Batna Rapporteur : M. Gaouaou MANAA Pr. Université Batna Examinateur : M. Abdelouaheb DAKHIA Pr. Université Biskra Année universitaire : 2012 - 2013 REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DÉMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTÈRE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE Université El Hadj Lakhdar – Batna Faculté des Lettres et des Langues École Doctorale de Français Thème Les Bases de Données Lexicographiques Panfrancophones : Algérie et Maroc Étude comparative Mémoire élaboré en vue de l'obtention du diplôme de Magistère Option : Sciences du langage Sous la direction de : Présenté et soutenu par : Pr. Gaouaou MANAA M. Samir CHELLOUAI Membres du jury : Président : M. Samir ABDELHAMID Pr. Université Batna Rapporteur : M. Gaouaou MANAA Pr. Université Batna Examinateur : M. Abdelouaheb DAKHIA Pr. Université Biskra Année universitaire : 2012 - 2013 A la mémoire de mon père à ma mère à mon épouse à mes frères et sœurs à ma belle-famille à tous mes amis REMERCIEMENTS L’aboutissement de ce travail n’aurait pas été possible sans la précieuse contribution de nombreuses personnes que je veux remercier ici. Je tiens tout d'abord à exprimer toute ma gratitude et mon respect à mon directeur de recherche, le Professeur Gaouaou MANAA, pour son encadrement, pour ses conseils utiles et pour sa disponibilité. -

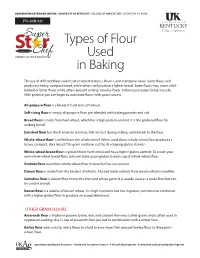

Types of Flour Used in Baking

FN-SSB.921 Types of Flour KNEADS A LITTLE DOUGH Used in Baking The use of different flours will result in varied textures, flavors, and nutritional value. Some flours will produce a heavy, compact bread, while others will produce a lighter bread. Some flours may cause a full- bodied or bitter flavor while others present a nutty, woodsy flavor. Follow your recipe for best results. With practice you can begin to substitute flours with good success. All-purpose flouris a blend of hard and soft wheat. Self-rising flouris simply all-purpose flour pre-blended with baking powder and salt. Bread flour is made from hard wheat, which has a high protein content. It is the preferred flour for making bread. Enriched flourhas the B-vitamins and iron, that are lost during milling, added back to the flour. Whole-wheat flouris milled from the whole kernel. When used alone, whole-wheat flour produces a heavy, compact, dark bread. The germ and bran cut the developing gluten strands. Whole-wheat bread flouris ground from hard wheat and has a higher gluten content. To create your own whole wheat bread flour, add one tablespoon gluten to each cup of whole-wheat flour. Graham flourresembles whole wheat flour in taste but has less protein. Durum flouris made from the hardest of wheats. A bread made entirely from durum wheat is inedible. Semolina flouris durum flour minus the bran and wheat germ. It is usually used as a pasta flour but can be used in breads. Kamut flouris a relative of durum wheat. It is high in protein but low in gluten, so it must be combined with a higher gluten flour to produce an acceptable bread. -

Whole-Wheat Flour Milling and the Effect of Durum Genotypes and Traits on Whole-Wheat Pasta Quality

WHOLE-WHEAT FLOUR MILLING AND THE EFFECT OF DURUM GENOTYPES AND TRAITS ON WHOLE-WHEAT PASTA QUALITY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Lingzhu Deng In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Program: Cereal Science June 2017 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title WHOLE-WHEAT FLOUR MILLING AND THE EFFECT OF DURUM GENOTYPES AND TRAITS ON WHOLE-WHEAT PASTA QUALITY By Lingzhu Deng The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Dr. Frank Manthey Chair Dr. Senay Simsek Dr. Julie Garden-Robinson Dr. Elias Elias Approved: November 1st, 2017 Dr. Richard Horsley Date Department Chair ABSTRACT An ultra-centrifugal mill was evaluated by determining the effect of mill configuration and seed conditioning on particle size distribution and quality of whole-wheat (WW) flour. Ultra-centrifugal mill configured with rotor speed of 12,000 rpm, screen aperture of 250 μm, and seed conditioning moisture of 9% resulted in a fine WW flour where 82% of particles were <150 µm, starch damage was 5.9%, and flour temperature was below 35°C. The single-pass and multi-pass milling systems were evaluated by comparing the quality of WW flour and the subsequent WW spaghetti they produced. Two single-pass mill configurations for an ultra-centrifugal mill were used (fine grind: 15,000 rpm with 250 μm mill screen aperture and coarse grind: 12,000 rpm with 1,000 μm mill screen aperture) to direct grind durum grain or to regrind millstreams from roller milling to make WW flour and WW spaghetti. -

GUIDE-M-P.Pdf

ROYAUME DU MAROC Dépôt légal : 2012MO2183 ISBN : 978-9954-604-02-1 Préface Une alimentation équilibrée est essentielle pour jouir d’une vie saine et active. Si la majorité des gens sont convaincus de la nécessité de bien se nourrir, peu ont une idée claire et précise de comment y parvenir. La pauvreté est l’une des principales causes des problèmes nutritionnels rencontrés dans les pays en développement. Toutefois, la malnutrition existe aussi dans les pays à revenu élevé. En fait, il existe deux sortes de malnutrition, diamétralement opposées. La première est due à un apport insuffisant d’aliments sains et de bonne qualité. La seconde résulte d’un apport excessif d’aliments souvent de mauvaise qualité. Pour bien se nourrir, la population doit disposer de ressources suffisantes, afin de produire et/ou se procurer les aliments nécessaires. Elle doit aussi être bien informée sur les modalités pratiques pour adopter un régime alimentaire sain. L’éducation nutritionnelle joue un rôle capital pour favoriser une bonne alimentation. Elle doit appliquer les découvertes les plus récentes des sciences nutritionnelles tout en tenant compte à la fois du contexte socio-économique et culturel. Elle doit aussi être conduite de façon à inciter véritablement la population à adopter des régimes alimentaires équilibrés et des modes de vie sains. Le présent Guide national de nutrition contribuera certainement à renforcer les actions d’éducation nutritionnelle. Ce document riche en informations pertinentes en matière de nutrition renforcera les actions d’éducation en aidant les professionnels de santé à dispenser des messages clairs, simples et efficaces pour inciter la population à adopter de bonnes habitudes alimentaires. -

Inauguration Sourdough Library 15 October 2013

Inauguration Sourdough Library 15 October 2013 Professor of Microbiology at the Department of Soil, Plant and Food Sciences University of Bari, Italy “History of bread” Marco Gobbetti 16 – 17 October, Sankt Vith (Belgium) Department of Soil, Plant and Food Science, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy Bread: «The ferment of life» For the Egyptians: a piece of merchandise.. For the Egyptians: Sacred value….”a gift of God or the gods” For the Jews.. sacred and transcendent value For the Christians..Eucharist For the Greeks..offered to the Divinity…medicinal purpose For the Latin.. vehicle for transmitting of the sacrum For the Romans..sign of purification Wall painting of the Tomb of Ramesses III, (1570-1070 b. C), XIX Dinasty Department of Soil, Plant and Food Science, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy Influence of the term «bread» on the common lexicon «Lord»«Companion» (from Old English(from cum vocabulary panis) hlaford) “to earn his bread” ““toremove eat unearnedbread from bread” his mouth” “man cannot live on bread alone” Department of Soil, Plant and Food Science, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy History and sourdough Egyptians (2000 B.C.) casually discovered a leavened dough; used foam of beer as a (unconscious) starter for dough leavening Romans (1° century A.D.) used to propagate the sourdough through back-slopping (Plinio il Vecchio, Naturalis Historia XVIII) Middle Age (1600): dawn of the use of baker’s yeast for bread Department of Soil, Plant and Food Science, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy Tacuini sanitatis (XI century): “among the six elements needed to keep daily wellness… foods and beverages… “ “…White bread: it improves the wellness but it must be completely fermented …“ (FromTheatrum sanitatis, XI Century) Department of Soil, Plant and Food Science, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy Pliny the elder wrote: “….Then, normally they do not even heat the dough, but they just use a bit of dough left from the day before, and it is undeniable that flour, by its nature, is leavened by an acid substance. -

Our Falconbridge Clubhouse

OCTOBER UPCOMING EVENTS October 2014 NEIGHBORHOOD NEWS falconbridgealliance.org [email protected] Fri. Oct. 3, 17 & 31 • 5:30pm TRAVELING PUB [email protected] Our Falconbridge Clubhouse: Mon. Oct. 6, 13, 20, 27 Some very good news! 2:00 pm Message from the president expected to increase rental income for MAH JONGG the FHA. Of course town home own- [email protected] ers who are also Alliance members Over the years we have received win on both scores. Thurs. Oct. 9 & 23 dozens of great ideas for expanding The Alliance is now preparing plans 9:30am the community activities supported to solicit bids for the most urgent task: WOMEN’S COFFEE KLATCH by the Alliance. But lack of an ap- remodeling the bathrooms. Both the [email protected] propriate facility has often blocked such plans. Now I’m very happy to FHA and Alliance boards will have to approve the bids and fund the work. Sat. Oct. 11 • 6:00pm report that the Alliance has reached Since both organizations operate with DINING CAR GOURMET CLUB agreement in principal with the FHA tight budgets, additional funding will [email protected] (townhome owners association) to greatly expand the use of the club- certainly be required. The Alliance is planning fund-raising events to let Sun. Oct. 12 • 5:00pm house for community activities. Since the clubhouse needs signifi- members of the Falconbridge com- ANNUAL MEMBERS munity contribute while enjoying the MEETING, cant improvements, the Alliance has agreed to provide half the cost of the improved clubhouse. See the “Club BOARD ELECTIONS, improvements in exchange for the Falconbridge” article in this newslet- POTLUCK SUPPER! increased usage.