Gloria Staffieri, Musicare La Storia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meyerbeer Was One of the Most Significant Opera Composers of All Time

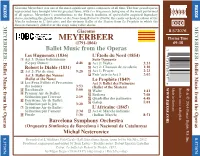

NAXOS NAXOS Giacomo Meyerbeer was one of the most significant opera composers of all time. The four grand operas represented here brought him his greatest fame, with Les Huguenots being one of the most performed of all operas. Meyerbeer’s contributions to the French tradition of opéra-ballet acquired legendary status, including the ghostly Ballet of the Nuns from Robert le Diable; the exotic orchestral colour of the Marche indienne in L’Africaine; and the virtuoso Ballet of the Skaters from Le Prophète in which the dancers famously glided over the stage using roller skates. DDD MEYERBEER: MEYERBEER: Giacomo 8.573076 MEYERBEER Playing Time (1791-1864) 69:38 Ballet Music from the Operas 7 Les Huguenots (1836) L’Étoile du Nord (1854) 47313 30767 1 Act 3: Danse bohémienne Suite Dansante Ballet Music from the Operas Ballet Music from (Gypsy Dance) 4:46 9 Act 2: Waltz 3:32 the Operas Ballet Music from Robert le Diable (1831) 0 Act 2: Chanson de cavalerie 1:18 2 Act 2: Pas de cinq 9:28 ! Act 1: Prayer 2:23 Act 3: Ballet des Nonnes @ Entr’acte to Act 3 2:02 (Ballet of the Nuns) Le Prophète (1849) 3 Les Feux Follets et Procession Act 3: Ballet des Patineurs 8 des nonnes 3:53 (Ballet of the Skaters) www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ 4 Bacchanale 5:00 # Waltz 1:41 & 5 Premier Air de Ballet: $ Redowa 7:08 Ꭿ Séduction par l’ivresse 2:19 % Quadrilles des patineurs 4:48 6 Deuxième Air de Ballet: 2014 Naxos Rights US, Inc. -

Catalogs Files 3508 Arengario 2017 Opera Web.Pdf

Bruno e Paolo Tonini. Fotografia di Tano D’Amico L’ARENGARIO Via Pratolungo 192 STUDIO BIBLIOGRAFICO 25064 Gussago (BS) Dott. Paolo Tonini e Bruno Tonini ITALIA Web www.arengario.it E-mail [email protected] Tel. (+39) 030 252 2472 Fax (+39) 030 252 2458 L’ARENGARIO STUDIO BIBLIOGRAFICO OPERA Ottocento e Novecento Libretti per musica e bozzetti scenografici originali dalla collezione di Alberto De Angelis EDIZIONI DELL’ARENGARIO 1 Il teatro lirico è basato su un fatto straordinario, di natura totalmente inverosimile ed arbitraria: esso si poggia su personaggi che vivono cantando, per cui il teatro musicale non ha rapporti con la realtà e può spaziare nell’infinito della fantasia musicale. Alfredo Casella Finito di stampare un giorno di settembre del 2017 Tiratura di 60 esemplari 2 3 Melodramma bibliografico “Vado raccogliendo libretti per musica da oltre 50 anni ed avendone ormai una collezione di più di 32.000 mi lusingo di poterne dire qualcosa. Nei primi anni della mia Raccolta, mi vedevo guardato con un sorrisetto di compatimento non scevro d’ironia... in attesa che la fede e la tenacia mi dessero ragione perché io invece venivo sempre più convincendomi che il libretto aveva pur la sua importanza, anche prescindendo dai difetti letterari e poetici. E continuavo a raccogliere, fiducioso... Ebbi così la soddisfazione di convincermi che non avevo lavorato invano e che la mia tenacia, la mia pazienza, la mia fede avevano avuto ragione della noncuranza, dell’incredulità, dell’ironia di tanti! Sono già più di 250 gli studiosi che per una ragione o per l’altra hanno trovato nella mia Collezione aiuto di notizie e fonte di studio” (Ulderico Rolandi, Il libretto per musica attraverso i tempi, Roma, Edizioni dell’Ateneo, 1951; pp. -

Catalogo Nr.32 Primavera 2009

LIBRERIA MUSICALE GALLINI VIA GORANI 8 - 20123 MILANO (ITALY) - TEL. e FAX. 0272.000.398 CATALOGO NR.32 PRIMAVERA 2009 INDICE: Biografie ......................................pag. 2 (da nr. 1 a 150) Libri di argomento musicale ..........pag. 10 (da nr. 151 a 238) Libri su strumenti musicali .............pag. 15 (da nr. 239 a 291) Spartiti d’opera per canto e pf ......pag. 19 (da nr. 292 a 435) Lettere autografe di musicisti ........pag. 29 (da nr. 436 a 454) Lettere autografe di letterati ..........pag. 31 (da nr. 455 a 504) Condizioni di vendita ................................. pag. 38 / 39 - 2 - BIOGRAFIE DI MUSICISTI: 1) AA.VV. (a cura di G.Taborelli e V.Crespi): “Ritratti di compositori”. Milano, Banco Lariano e Amici della Scala 1990. 4° leg. ed. con sovracoperta pp.160 con moltissimi ritratti di compositori a colori e in b.n. Ricca bibliografia. Un semiologo dell’immagine (A.Veca), due storici dell’arte (V. Crespi e G.Fonio), uno storico della musica (F. Pulcini) e uno storico della cultura (G. Taborelli) prendono in esame una serie di ritratti di compositori dipinti dal rinascimento ai nostri giorni. A volte la loro effigie, a volte quella che posteri reverenti hanno loro attribuito. Molto bello e interessante. € 75,00 2) Félix CLEMENT: “Les musiciens célèbres depuis le seizième siècle jusqu’a nos jours Paris, Hachette 1873 (II edizione). 8° leg. edit., tit. oro al dorso, pp. XI + 660. Bibliografia. F.t. 40 ritratti di musicisti (acqueforti di Masson, Delblois e Massard). Ritratti di Gluck, Mondoville e della famiglia Mozart, riproduzioni eliografiche di incisioni settecentesche di A Durand. -

The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert Le Diable Online

cXKt6 [Get free] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Online [cXKt6.ebook] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Pdf Free Richard Arsenty ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4398313 in Books 2009-03-01Format: UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.00 x .50 x 5.70l, .52 #File Name: 1847189644180 pages | File size: 19.Mb Richard Arsenty : The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Liobretto for Meyerbeer's "Robert le Diable"By radamesAn excellent publication which contained many stage directions not always reproduced in the nineteenth-century vocal scores and a fine translation. Useful at a time of renewed interest in this opera at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden Giacomo Meyerbeer, one of the most important and influential opera composers of the nineteenth century, enjoyed a fame during his lifetime hardly rivaled by any of his contemporaries. This eleven volume set provides in one collection all the operatic texts set by Meyerbeer in his career. The texts offer the most complete versions available. Each libretto is translated into modern English by Richard Arsenty; and each work is introduced by Robert Letellier. In this comprehensive edition of Meyerbeer's libretti, the original text and its translation are placed on facing pages for ease of use. About the AuthorRichard Arsenty, a native of the U.S. -

Days of Bliss Are in Store: Antonino Pasculli's "Gran Trio Concertante

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Days of Bliss Are in Store: Antonino Pasculli's Gran Trio Concertante per Violino, Oboe, e Pianoforte su Motivi del Guglielmo Tell di Rossini Anna Pennington Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC DAYS OF BLISS ARE IN STORE: ANTONINO PASCULLI’S GRAN TRIO CONCERTANTE PER VIOLINO, OBOE, E PIANOFORTE SU MOTIVI DEL GUGLIELMO TELL DI ROSSINI By ANNA PENNINGTON A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music. Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2007 Copyright © 2007 Anna Pennington All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Anna Pennington defended on May 7, 2007. ______________________________ Eric Ohlsson Professor Directing Treatise ______________________________ Richard Clary Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Frank Kowalsky Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the generous encouragement of Eric Ohlsson in completing this project, I am greatly indebted. I also wish to thank Sandro Caldini and Olga Visentini, for their unselfish help in obtaining the trio. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................... v -

Opera Productions Old and New

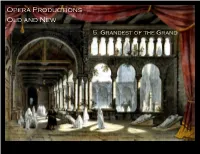

Opera Productions Old and New 5. Grandest of the Grand Grand Opera Essentially a French phenomenon of the 1830s through 1850s, although many of its composers were foreign. Large-scale works in five acts (sometimes four), calling for many scene-changes and much theatrical spectacle. Subjects taken from history or historical myth, involving clear moral choices. Highly demanding vocal roles, requiring large ranges, agility, stamina, and power. Orchestra more than accompaniment, painting the scene, or commenting. Substantial use of the chorus, who typically open or close each act. Extended ballet sequences, in the second or third acts. Robert le diable at the Opéra Giacomo Meyerbeer (Jacob Liebmann Beer, 1791–1864) Germany, 1791 Italy, 1816 Paris, 1825 Grand Operas for PAris 1831, Robert le diable 1836, Les Huguenots 1849, Le prophète 1865, L’Africaine Premiere of Le prophète, 1849 The Characters in Robert le Diable ROBERT (tenor), Duke of Normandy, supposedly the offspring of his mother’s liaison with a demon. BERTRAM (bass), Robert’s mentor and friend, but actually his father, in thrall to the Devil. ISABELLE (coloratura soprano), Princess of Sicily, in love with Robert, though committed to marry the winner of an upcoming tournament. ALICE (lyric soprano), Robert’s foster-sister, the moral reference-point of the opera. Courbet: Louis Guéymard as Robert le diable Robert le diable, original design for Act One Robert le diable, Act One (Chantal Thomas, designer) Robert le diable, Act Two (Chantal Thomas, designer) Robert le diable, Act -

Ludwig Van Beethoven Hdt What? Index

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN HDT WHAT? INDEX LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1756 December 8, Wednesday: The Emperor’s son Maximilian Franz, the Archduke who in 1784 would become the patron of the young Ludwig van Beethoven, was born on the Emperor’s own birthday. Christoph Willibald Gluck’s dramma per musica Il rè pastore to words of Metastasio was being performed for the initial time, in the Burgtheater, Vienna, in celebration of the Emperor’s birthday. ONE COULD BE ELSEWHERE, AS ELSEWHERE DOES EXIST. ONE CANNOT BE ELSEWHEN SINCE ELSEWHEN DOES NOT. Ludwig van Beethoven “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1770 December 16, Sunday: This is the day on which we presume that Ludwig van Beethoven was born.1 December 17, Monday: Ludwig van Beethoven was baptized at the Parish of St. Remigius in Bonn, Germany, the 2d and eldest surviving of 7 children born to Johann van Beethoven, tenor and music teacher, and Maria Magdalena Keverich (widow of M. Leym), daughter of the chief kitchen overseer for the Elector of Trier. Given the practices of the day, it is presumed that the infant had been born on the previous day. NEVER READ AHEAD! TO APPRECIATE DECEMBER 17TH, 1770 AT ALL ONE MUST APPRECIATE IT AS A TODAY (THE FOLLOWING DAY, TOMORROW, IS BUT A PORTION OF THE UNREALIZED FUTURE AND IFFY AT BEST). 1. Q: How come Austrians have the rep of being so smart? A: They’ve managed somehow to create the impression that Beethoven, born in Germany, was Austrian, while Hitler, born in Austria, was German! HDT WHAT? INDEX LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1778 March 26, Thursday: In the Academy Room on the Sternengasse of Cologne, Ludwig van Beethoven appeared in concert for the initial time, with his father and another child-student of his father. -

16 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert Le Diable, 1831. the Nuns' Ballet. Meyerbeer's Synesthetic Cocktail Debuts at the Paris Opera

Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/grey/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/GREY_a_00030/689033/grey_a_00030.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert le diable, 1831. The nuns’ ballet. Meyerbeer’s synesthetic cocktail debuts at the Paris Opera. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. 16 Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/grey/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/GREY_a_00030/689033/grey_a_00030.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 The Prophet and the Pendulum: Sensational Science and Audiovisual Phantasmagoria around 1848 JOHN TRESCH Nothing is more wonderful, nothing more fantastic than actual life. —E.T.A. Hoffmann, “The Sand-Man” (1816) The Fantastic and the Positive During the French Second Republic—the volatile period between the 1848 Revolution and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s 1851 coup d’état—two striking per - formances fired the imaginations of Parisian audiences. The first, in 1849, was a return: after more than a decade, the master of the Parisian grand opera, Giacomo Meyerbeer, launched Le prophète , whose complex instrumentation and astound - ing visuals—including the unprecedented use of electric lighting—surpassed even his own previous innovations in sound and vision. The second, in 1851, was a debut: the installation of Foucault’s pendulum in the Panthéon. The installation marked the first public exposure of one of the most celebrated demonstrations in the history of science. A heavy copper ball suspended from the former cathedral’s copula, once set in motion, swung in a plane that slowly traced a circle on the marble floor, demonstrating the rotation of the earth. In terms of their aim and meaning, these performances might seem polar opposites. -

![ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie Royale], Paris, November 21, 1831](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1791/robert-le-diable-music-by-giacomo-meyerbeer-libretto-by-eug%C3%A8ne-scribe-germain-delavigne-first-performance-op%C3%A9ra-acad%C3%A9mie-royale-paris-november-21-1831-1191791.webp)

ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie Royale], Paris, November 21, 1831

ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie royale], Paris, November 21, 1831 Robert, son of Bertha, daughter of the Duke of Normandy (who has been seduced by the Devil), wanders to Palermo in Sicily, where he falls in love with the King's daughter, Isabella, and intends to joust in a tournament to win her. His companion, Bertram (in reality his satanic father), forestalls him at every juncture. A compatriot, the minstrel Raimbaut, warns the company about Robert the Devil, and is about to be hanged when Robert's foster sister Alice appears to save him. She has followed Robert with a message from his dead mother; Robert confides to her his love for Isabella, who has banished him because of his jealousy. Alice promises to help and asks in return that she be allowed to marry Raimbaut. When Bertram enters, she recognizes him and hides. Bertram induces Robert to gamble away all his substance. Alice intercedes for Robert with Isabella, who presents him with a new suit of armor to fight the Prince of Granada, but Bertram lures him away from combat, and the Prince wins Isabella. In the cavern of St. Irene, Raimbaut waits for Alice but is tempted by Bertram with money, which he leaves to spend. Alice enters on a scene which betrays Bertram as an unholy spirit, and in spite of clinging to her cross, is about to be destroyed by Bertram when Robert enters. The young man is desperate and ready to resort to magic arts. -

Lucia Di Lammermoor GAETANO DONIZETTI MARCH 3 – 11, 2012

O p e r a B o x Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .9 Reference/Tracking Guide . .10 Lesson Plans . .12 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .44 Flow Charts . .49 Gaetano Donizetti – a biography .............................56 Catalogue of Donizetti’s Operas . .58 Background Notes . .64 Salvadore Cammarano and the Romantic Libretto . .67 World Events in 1835 ....................................73 2011–2012 SEASON History of Opera ........................................76 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .87 così fan tutte WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART The Standard Repertory ...................................91 SEPTEMBER 25 –OCTOBER 2, 2011 Elements of Opera .......................................92 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................96 silent night KEVIN PUTS Glossary of Musical Terms . .101 NOVEMBER 12 – 20, 2011 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .105 werther Evaluation . .108 JULES MASSENET JANUARY 28 –FEBRUARY 5, 2012 Acknowledgements . .109 lucia di lammermoor GAETANO DONIZETTI MARCH 3 – 11, 2012 madame butterfly mnopera.org GIACOMO PUCCINI APRIL 14 – 22, 2012 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. -

16 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert Le Diable, 1831. the Nuns' Ballet

Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert le diable, 1831. The nuns’ ballet. Meyerbeer’s synesthetic cocktail debuts at the Paris Opera. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. 16 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00030 by guest on 25 September 2021 The Prophet and the Pendulum: Sensational Science and Audiovisual Phantasmagoria around 1848 JOHN TRESCH Nothing is more wonderful, nothing more fantastic than actual life. —E.T.A. Hoffmann, “The Sand-Man” (1816) The Fantastic and the Positive During the French Second Republic—the volatile period between the 1848 Revolution and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s 1851 coup d’état—two striking per - formances fired the imaginations of Parisian audiences. The first, in 1849, was a return: after more than a decade, the master of the Parisian grand opera, Giacomo Meyerbeer, launched Le prophète , whose complex instrumentation and astound - ing visuals—including the unprecedented use of electric lighting—surpassed even his own previous innovations in sound and vision. The second, in 1851, was a debut: the installation of Foucault’s pendulum in the Panthéon. The installation marked the first public exposure of one of the most celebrated demonstrations in the history of science. A heavy copper ball suspended from the former cathedral’s copula, once set in motion, swung in a plane that slowly traced a circle on the marble floor, demonstrating the rotation of the earth. In terms of their aim and meaning, these performances might seem polar opposites. Opera aficionados have seen Le prophète as the nadir of midcentury bad taste, demanding correction by an idealist conception of music. Grand opera in its entirety has been seen as mass-produced phantasmagoria, mechani - cally produced illusion presaging the commercial deceptions of the society of the spectacle. -

Stephanie Schroedter Listening in Motion and Listening to Motion. the Concept of Kinaesthetic Listening Exemplified by Dance Compositions of the Meyerbeer Era

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Berner Fachhochschule: ARBOR Stephanie Schroedter Listening in Motion and Listening to Motion. The Concept of Kinaesthetic Listening Exemplified by Dance Compositions of the Meyerbeer Era Musical life in Paris underwent profound and diverse changes between the July Monar- chy and the Second Empire. One reason for this was the availability of printed scores for a broader public as an essential medium for the distribution of music before the advent of mechanical recordings. Additionally, the booming leisure industry encouraged music commercialization, with concert-bals and café-concerts, the precursors of the variétés, blurring the boundaries between dance and theatre performances. Therefore there was not just one homogeneous urban music culture, but rather a number of different music, and listening cultures, each within a specific urban setting. From this extensive field I will take a closer look at the music of popular dance or, more generally, movement cultures. This music spanned the breadth of cultural spaces, ranging from magnificent ballrooms – providing the recognition important to the upper-classes – to relatively modest dance cafés for those who enjoyed physical exercise above social distinction. Concert halls and musical salons provided a venue for private audiences who preferred themoresedateactivityoflisteningtostylized dance music rather than dancing. Café- concerts and popular concert events offered diverse and spectacular entertainment