Ahmed Vâsıf Efendi (Ca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

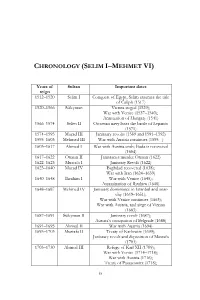

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

Sex Offender Notification Celtics Make 10-Year, $25M Social Justice Commitment by CARL by MICHAEL P

Search for The Westfield News Westfield350.comTheThe Westfield WestfieldNews News Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIME IS THE ONLY WEATHER CRITIC WITHOUT TONIGHT AMBITION.” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com VOL. 86 NO. 151 TUESDAY, JUNE 27, 2017 75 cents $1.00 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2020 VOL. 89 NO. 219 Mandated flu vaccine added to Westfield school immunization policy By AMY PORTER nale behind it, but I know there Staff Writer are a lot of people who are going WESTFIELD – The Westfield to be upset about it, so I just Public Schools immunization want to make sure everybody policy was amended during a understands our hands are tied. special Westfield School We can’t vote to not do it because Committee meeting Sept. 8 to it’s law, or policy, or regulation add a required flu vaccine for all — whatever it is – that comes students per Gov. Charlie down, that is in the purview of Westfield Board of Health nurse Debra Mulvenna applies a band-aid to a Baker’s recent mandate. The the governor.” senior citizen during a past flu shot clinic at the Westfield Council on Aging. policy will now go to a regular Diaz said there are pending (THE WESTFIELD NEWS PHOTO) School Committee meeting for a cases in the courts against the vote. required flu immunization The new influenza require- already. ment. which is one dose vaccine Mayhew said Baker may over- Flu clinics good practice for the current flu season, must turn the mandate. “There’s be received annually by Dec. -

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan The relationship between the Ottomans and the Christians did not evolve around continuous hostility and conflict, as is generally assumed. The Ottomans employed Christians extensively, used Western know-how and technology, and en- couraged European merchants to trade in the Levant. On the state level, too, what dictated international diplomacy was not the religious factors, but rather rational strategies that were the results of carefully calculated priorities, for in- stance, several alliances between the Ottomans and the Christian states. All this cooperation blurred the cultural bound- aries and facilitated the flow of people, ideas, technologies and goods from one civilization to another. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Christians in the Service of the Ottomans 3. Ottoman Alliances with the Christian States 4. Conclusion 5. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Citation Introduction Cooperation between the Ottomans and various Christian groups and individuals started as early as the beginning of the 14th century, when the Ottoman state itself emerged. The Ottomans, although a Muslim polity, did not hesitate to cooperate with Christians for practical reasons. Nevertheless, the misreading of the Ghaza (Holy War) literature1 and the consequent romanticization of the Ottomans' struggle in carrying the banner of Islam conceal the true nature of rela- tions between Muslims and Christians. Rather than an inevitable conflict, what prevailed was cooperation in which cul- tural, ethnic, and religious boundaries seemed to disappear. Ÿ1 The Ottomans came into contact and allied themselves with Christians on two levels. Firstly, Christian allies of the Ot- tomans were individuals; the Ottomans employed a number of Christians in their service, mostly, but not always, after they had converted. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Turcicum Imperium, Carolus Allard Exc. Stock#: 49424 Map Maker: Allard Date: 1680 circa Place: Amsterdam Color: Hand Colored Condition: VG Size: 22 x 18 inches Price: SOLD Description: Rare Carel Allard Map of the Turkish Empire. A fine depiction of the Ottoman Empire on the eve of the Great Turkish War (1683-1699), which marked a turning point in the fortunes of the empire and that of Europe. Up to the 1680s, the European Christian powers of Habsburg, Austria, Russia, Poland-Lithuania and the Republic of Venice, had separately fought the Ottoman Empire in numerous wars over the last century only to arrive at a stalemate. The Turks had largely kept the great gains they had made during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (ruled 1520-66), in spite of innumerable attempts by the Christian powers to dislodge them. The line of control generally ran through Croatia, the middle of Hungary and northern Romania, to what is now Moldova, with the Ottoman lands being to the south of the line. In 1683, an Ottoman army broke out of Hungary to besiege Vienna, the Habsburg capital. This sent a shockwave throughout Europe, and only the intervention of Poland's King Jan Sobieski saved the city. In 1684, the region's main Christian powers formed the Holy League, marking the first time that they all joined forces to fight the Ottomans. This quickly turned the tables, as the Allies inflicted a series of severe defeats on the Turks. -

Political and Economic Transition of Ottoman Sovereignty from a Sole Monarch to Numerous Ottoman Elites, 1683–1750S

Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 70 (1), 49 – 90 (2017) DOI: 10.1556/062.2017.70.1.4 POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC TRANSITION OF OTTOMAN SOVEREIGNTY FROM A SOLE MONARCH TO NUMEROUS OTTOMAN ELITES, 1683–1750S BIROL GÜNDOĞDU Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen Historisches Institut, Osteuropäische Geschichte Otto-Behaghel-Str. 10, Haus D Raum 205, 35394 Gießen, Deutschland e-mail: [email protected] The aim of this paper is to reveal the transformation of the Ottoman Empire following the debacles of the second siege of Vienna in 1683. The failures compelled the Ottoman state to change its socio- economic and political structure. As a result of this transition of the state structure, which brought about a so-called “redistribution of power” in the empire, new Ottoman elites emerged from 1683 until the 1750s. We have divided the above time span into three stages that will greatly help us com- prehend the Ottoman transition from sultanic authority to numerous autonomies of first Muslim, then non-Muslim elites of the Ottoman Empire. During the first period (1683–1699) we see the emergence of Muslim power players at the expense of sultanic authority. In the second stage (1699–1730) we observe the sultans’ unsuccessful attempts to revive their authority. In the third period (1730–1750) we witness the emergence of non-Muslim notables who gradually came into power with the help of both the sultans and external powers. At the end of this last stage, not only did the authority of Ottoman sultans decrease enormously, but a new era evolved where Muslim and non-Muslim leading figures both fought and co-operated with one another for a new distribution of wealth in the Ottoman Empire. -

Islamic Gunpowder Empires : Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals / Douglas E

“Douglas Streusand has contributed a masterful comparative analysis and an up-to- S date reinterpretation of the significance of the early modern Islamic empires. This T book makes profound scholarly insights readily accessible to undergraduate stu- R dents and will be useful in world history surveys as well as more advanced courses.” —Hope Benne, Salem State College E U “Streusand creatively reexamines the military and political history and structures of the SAN Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal empires. He breaks down the process of transformation and makes their divergent outcomes comprehensible, not only to an audience of special- ists, but also to undergraduates and general readers. Appropriate for courses in world, early modern, or Middle Eastern history as well as the political sociology of empires.” D —Linda T. Darling, University of Arizona “Streusand is to be commended for navigating these hearty and substantial historiogra- phies to pull together an analytical textbook which will be both informative and thought provoking for the undergraduate university audience.” GUNPOWDER EMPIRES —Colin Mitchell, Dalhousie University Islamic Gunpowder Empires provides an illuminating history of Islamic civilization in the early modern world through a comparative examination of Islam’s three greatest empires: the Otto- IS mans (centered in what is now Turkey), the Safavids (in modern Iran), and the Mughals (ruling the Indian subcontinent). Author Douglas Streusand explains the origins of the three empires; compares the ideological, institutional, military, and economic contributors to their success; and L analyzes the causes of their rise, expansion, and ultimate transformation and decline. Streusand depicts the three empires as a part of an integrated international system extending from the At- lantic to the Straits of Malacca, emphasizing both the connections and the conflicts within that AMIC system. -

Turkish Plastic Arts

Turkish Plastic Arts by Ayla ERSOY REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM PUBLICATIONS © Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism General Directorate of Libraries and Publications 3162 Handbook Series 3 ISBN: 978-975-17-3372-6 www.kulturturizm.gov.tr e-mail: [email protected] Ersoy, Ayla Turkish plastic arts / Ayla Ersoy.- Second Ed. Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2009. 200 p.: col. ill.; 20 cm.- (Ministry of Culture and Tourism Publications; 3162.Handbook Series of General Directorate of Libraries and Publications: 3) ISBN: 978-975-17-3372-6 I. title. II. Series. 730,09561 Cover Picture Hoca Ali Rıza, İstambol voyage with boat Printed by Fersa Ofset Baskı Tesisleri Tel: 0 312 386 17 00 Fax: 0 312 386 17 04 www.fersaofset.com First Edition Print run: 3000. Printed in Ankara in 2008. Second Edition Print run: 3000. Printed in Ankara in 2009. *Ayla Ersoy is professor at Dogus University, Faculty of Fine Arts and Design. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 Sources of Turkish Plastic Arts 5 Westernization Efforts 10 Sultans’ Interest in Arts in the Westernization Period 14 I ART OF PAINTING 18 The Primitives 18 Painters with Military Background 20 Ottoman Art Milieu in the Beginning of the 20th Century. 31 1914 Generation 37 Galatasaray Exhibitions 42 Şişli Atelier 43 The First Decade of the Republic 44 Independent Painters and Sculptors Association 48 The Group “D” 59 The Newcomers Group 74 The Tens Group 79 Towards Abstract Art 88 Calligraphy-Originated Painters 90 Artists of Geometrical Non-Figurative -

The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa's Diary

Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici pertinentes Volume 2 Paulina D. Dominik (Ed.) The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa’s Diary »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (1760) With an introduction by Stanisław Roszak Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici pertinentes Edited by Richard Wittmann Memoria. Fontes Minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici Pertinentes Volume 2 Paulina D. Dominik (Ed.): The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa’s Diary »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (1760) With an introduction by Stanisław Roszak © Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, Bonn 2017 Redaktion: Orient-Institut Istanbul Reihenherausgeber: Richard Wittmann Typeset & Layout: Ioni Laibarös, Berlin Memoria (Print): ISSN 2364-5989 Memoria (Internet): ISSN 2364-5997 Photos on the title page and in the volume are from Regina Salomea Pilsztynowa’s memoir »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (Echo na świat podane procederu podróży i życia mego awantur), compiled in 1760, © Czartoryski Library, Krakow. Editor’s Preface From the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to Istanbul: A female doctor in the eighteenth-century Ottoman capital Diplomatic relations between the Ottoman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Com- monwealth go back to the first quarter of the fifteenth century. While the mutual con- tacts were characterized by exchange and cooperation interrupted by periods of war, particularly in the seventeenth century, the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699) marked a new stage in the history of Ottoman-Polish relations. In the light of the common Russian danger Poland made efforts to gain Ottoman political support to secure its integrity. The leading Polish Orientalist Jan Reychman (1910-1975) in his seminal work The Pol- ish Life in Istanbul in the Eighteenth Century (»Życie polskie w Stambule w XVIII wieku«, 1959) argues that the eighteenth century brought to life a Polish community in the Ottoman capital. -

2Artboard 1 Copy

The First One Who Divided Their Countries and Displaced Them Suleiman the Magnificent Inaugurated the Kurdish “Bloodbath” History is merciless. Leaders and headmen shall be aware that one mistake may lead a nation to damage. Sometimes, it may rather eliminate it. This is what happened to Kurds and their relationship with the Ottoman Empire. It started with mutual concern between the two parties. It was followed by an alliance that quickly ended and turned into hostility that caused bloody massacres from which Kurds suffered until today. The story details date back to (1514 AD) when Idris Bitlisi, the leader of Kurds at that time, made a political deal with Selim I (1520 -1512). The deal was that Kurds should help Selim to gain victory over the Safavid state; in return, Ottoman Sultan shall recognize the autonomy of Kurds and give them freedom to form their own army and in addition; not to interfere in their internal affairs. Indeed, the deal was made and Selim I gained victory over Safavids in Chaldiran (1514 AD). The deal between Kurds and Turkish was named Chaldiran. The situation did not last long; as soon as Selim I died (1520 AD), everything changed. Although alliances made between countries do not depend on the life or death of people, this was not applicable to Turkish sultans as whenever one of them superseded, he breached the covenant of his predecessor and so on. Thus, they were known as the Empire of breaching covenants. This was the first mistake of Kurds, even if they realized it too late. -

The Influence of Ottoman Empire on the Conservation of the Architectural Heritage in Jerusalem

Indonesian Journal of Islam and Muslim Societies Vol. 10, no. 1 (2020), pp. 127-151, doi : 10.18326/ijims.v10i1. 127-151 The Influence of Ottoman Empire on the conservation of the architectural heritage in Jerusalem Ziad M. Shehada University of Malaya E-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.18326/ijims.v10i1.127-151 Abstract Jerusalem is one of the oldest cities in the world. It was built by the Canaanites in 3000 B.C., became the first Qibla of Muslims and is the third holiest shrine after Mecca and Medina. It is believed to be the only sacred city in the world that is considered historically and spiritually significant to Muslims, Christians, and Jews alike. Since its establishment, the city has been subjected to a series of changes as a result of political, economic and social developments that affected the architectural formation through successive periods from the beginning leading up to the Ottoman Era, which then achieved relative stability. The research aims to examine and review the conservation mechanisms of the architectural buildings during the Ottoman rule in Jerusalem for more than 400 years, and how the Ottoman Sultans contributed to revitalizing and protecting the city from loss and extinction. The researcher followed the historical interpretive method using descriptive analysis based on a literature review and preliminary study to determine Ottoman practices in conserving the historical and the architectural heritage of Jerusalem. The research found that the Ottoman efforts towards conserving the architectural heritage in Jerusalem fell into four categories (Renovation, Restoration, Reconstruction, and Rehabilitation). The Ottomans 127 IJIMS: Indonesian Journal of Islam and Muslim Societies, Volume 10, Number 1, June 2020:127-151 focused on the conservation of the existing buildings rather than new construction because of their respect for the local traditions and holy places. -

The Türk in Aşıkpaşazâde: a Private Individual's Ottoman History

The Türk in Aşıkpaşazâde: A Private Individual’s Ottoman History Murat Cem Mengüç* Aşıkpazâde’deki Türk: Bir Özel Şahsın Osmanlı Tarihi Öz 15. yüzyılda Osmanlı aydınları tarih kitaplarını sivil güçlerini uyguladıkları bir platform olarak kullandılar. Bu makale Aşıkpaşazâde ve onun Kitab-ı Tevarih-i Ali Osman isimli Osmanlı tarihine odaklanıyor. Temel argümanı, bu kitabın sivillerin Osmanlı kimliği ve meşrutiyetinin oluşturulmasını nasıl etkilediklerinin bir örneği olduğu. Makale erken dönem Osmanlı tarih kitaplarında açık bir Türkçü söylemin ortaya çıkışını ve Aşıkpaşazâde’nin bu oluşumdaki rolünü inceliyor. Aynı zamanda, Halil İnalcık ve Jean Jacques Rousseau’nun saptamalarına dayanarak Aşıkpaşazâde’nin hayatını teorik olarak irdeliyor. Aşıkpaşazâde’yi bir private individual (özel şahıs) ola- rak tanımlayan bu makale, bu gibi bireylerle erken modern dönem Batı devletleri ara- sında varolduğu kabul edilen politik güç paylaşımı dinamiklerinin 15. yüzyıl Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda da varolduğunun altını çiziyor. Anahtar kelimeler: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu, tarih, tarih yazımı, kimlik, Türk, Türk- men, Aşıkpaşazâde, Halil İnalcık, Jean Jacques Rousseau. And just as the battle with infidel is God’s work and the sultans and warriors who have engaged in it have acquired sanctity, so the recording of their deeds is a holy work, and the author is as entitled as they to a fatiha for the repose of his soul. V. L. Ménage1 * Seton Hall University. 1 V. L. Ménage, “The Beginnings of Ottoman Historiography,” Historians of the Middle East, eds. P. M. Holt and Bernard Lewis, London: Oxford University Press, 1964, 178. Osmanlı Araştırmaları / The Journal of Ottoman Studies, XLIV (2014), 45-66 45 THE TÜRK IN AŞIKPAŞAZÂDE I summarized and wrote down the words and the legends about the Ottomans, filled with events. -

Special List 391 1

special list 391 1 RICHARD C.RAMER Special List 391 Military 2 RICHARDrichard c. C.RAMER ramer Old and Rare Books 225 east 70th street . suite 12f . new york, n.y. 10021-5217 Email [email protected] . Website www.livroraro.com Telephones (212) 737 0222 and 737 0223 Fax (212) 288 4169 November 9, 2020 Special List 391 Military Items marked with an asterisk (*) will be shipped from Lisbon. SATISFACTION GUARANTEED: All items are understood to be on approval, and may be returned within a reasonable time for any reason whatsoever. VISITORS BY APPOINTMENT special list 391 3 Special List 391 Military Regulations for a Military Academy 1. [ACADEMIA MILITAR, Santiago de Chile]. Reglamento de la Academia Militar ... [text begins:] Debiendo el Director de la Academia militar someterse al reglamento que por el articulo 3º del decreto de 19 de julio del presente ano ha de servirle de pauta .... [Santiago de Chile]: Imprenta de la Opinion, dated 29 August 1831. 4°, early plain wrap- pers (soiled, stained). Caption title. Light stains and soiling. In good condition. 33 pp. $500.00 FIRST and ONLY EDITION of these regulations for the second incarnation of the Academia Militar, ancestor of Chile’s present Escuela Militar. They specify admission requirements, a four-year course of study with the content of each course (pp. 17-24) and the exams (pp. 24-28), what the cadets will be doing every hour of every day, and even how often they will shave and change their linen. Also covered are the duties of the director, sub-director, faculty, chaplain, surgeon, bursar, and doorman.