Psion: the Last Computer [Printer-Friendly] • Channel Register Page 1 of 33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORKABOUT PRO™ 3 Works As Hard As You Do

WORKABOUT PRO™ 3 Works as hard as you do The needs of businesses are changing almost daily, creating a demand for a fleet of handheld computers that can keep up. Introducing the latest innovation from Psion Teklogix – The WORKABOUT PRO 3. Intelligent, rugged and most importantly flexible, the Psion WORKABOUT PRO 3 is a new breed of handheld computer that delivers the choice of numerous hardware add-ons, software applications and upgrades, making it work as hard as you do. WORKABOUT PRO™ 3 The Flexible, Expandable, Rugged Handheld Computer Makes the Most of Mobility Created for the mobile worker, the WORKABOUT PRO 3 is ideal for employees across a range of industries, including mobile field services, logistics, warehousing, transportation, manufacturing and more. Its impressive flexibility enables you to supply one device to meet many requirements; the WORKABOUT PRO 3 is built to be a key member of your IT infrastructure. The leading product in its category, the WORKABOUT PRO 3 allows you to get exactly the device that you need. In addition, you have the opportunity to get the add-ons you need today and the ability to add more features at any point, as business needs change. The number of add-ons and software applications you can attach is endless, so whether it’s a camera for a traffic officer or a GPS module used to track and trace delivery locations – there is a solution for every application. Features & Benefits As Adaptable As You Are It Builds on Mobility The hardware expansion slots of the The WORKABOUT PRO 3’s Natural CASE STUDY WORKABOUT PRO 3 make adding Task Support™ means mobile workers new modules fast and easy – saving get the job done faster and more significant time and money. -

OPL – Die Open Programming Language Die Lösung Zur Entwicklung Von Mobilen Anwendungen?

OPL – Die Open Programming Language Die Lösung zur Entwicklung von mobilen Anwendungen? Martin Dehler Schumannstraße 18 67061 Ludwigshafen [email protected] Abstract: Die Open Programming Language (OPL) ist eine unter der Lesser Gnu Public Licence frei verfügbare Programmiersprache für das derzeit am weitesten verbreitete Smartphone Betriebssystem von Symbian. Mit seiner BASIC ähnlichen Syntax, der kostenlosen Verfügbarkeit von Runtime und Entwicklungsumgebung und der möglichen Nutzung der kompletten C++ API über OPX Erweiterungen hat OPL das Potential, die Entwicklung mobiler Software wesentlich zu erleichtern und damit die Verbreitung von mobilem Computing in der Medizin nachhaltig zu fördern. 1 Mobile medizinische Software von und für Jedermann? Im Gesundheitswesen findet elektronische Datenverarbeitung (EDV) eine immer größere Beachtung. Insbesondere medizinische Softwarelösungen für mobile Endgeräte, die direkt beim Patienten eingesetzt werden können, bieten das Potenzial, eine weite Verbreitung zu finden. Vom Einsatz mobiler medizinischer Anwendungen erhofft man sich eine Verbesserung von Arbeitsprozessen, der Qualität der erbrachten Leistungen und nicht zuletzt eine Erhöhung der Wirtschaftlichkeit. Eine möglichst weite Verbreitung mobiler medizinischer EDV-Anwendungen setzt sowohl eine weit verbreitete Hardwareplattform, als auch eine geeignete Programmier- sprache voraus. Sowohl für die Hardwareplattform, als auch für die Programmiersprache wäre es wünschenswert, wenn sie nur geringe Investitionskosten erfordern würden. Industrielösungen, -

Mobile Commerce Business Models and Technologies Towards Success

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 2003 Mobile commerce business models and technologies towards success Pinar Acar Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Acar, Pinar, "Mobile commerce business models and technologies towards success" (2003). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MS in Information Technology Capstone Thesis Pinar Nilgul1 Acar 5/15/2003 Mobile Commerce Business Models and Technologies Towards Success By Pinar Nilgun Acar Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree ofMaster of Science in Information Technology Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences 5/15/2003 1 Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Master of Science in Information Technology Thesis Approval Form Student Name: Pinar Nilgun Acar Project Title: Mobile Commerce Business Models and Technologies Towards Success Thesis Committee Name Signature Date Michael Floeser Chair Ed Holden Committee Member Jack Cook Committee Member Thesis Reproduction Permission Form Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences I Master of Science in Information Technology Title I, Pinar Acar. hereby grant permission to the Wallace Library of the Rochester Institute of Technology to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction must not be for commercial use Dr profit. -

WORKABOUT PRO the Flexible, Expandable Workhorse Psionteklogix.Com

WORKABOUT PRO The Flexible, Expandable Workhorse psionteklogix.com Something’s very wrong if you have to throw out your fleet of handheld computers just because your needs change. At Psion Teklogix, we take a different approach. The WORKABOUT PRO has hardware expansion slots that make adding new modules fast and easy – there’s a whole range of add-ons already available – everything from fingerprint scanners to the largest selection of RFID readers on any handheld device. Period. It just might be the most flexible, intelligent, rugged handheld computer ever made... www.psionteklogix.com WORKABOUT PRO The Flexible, Expandable Rugged Handheld Computer THE MobILE workHorSE Let’s face it: you have no idea what tomorrow will bring. The rugged handheld computer you choose today may not be right when your needs change. Unless you choose the legendary WORKABOUT PRO. It’s built on the Modulus™ platform, so it’s easily Meter Reading extended using a wide range of hardware modules – anything from passport readers and fingerprint scanners to WAN radios, laser scanners, imagers and Bluetooth® printers. Plus a growing range of connectivity peripherals (RS232, USB...) that mean you’ll never regret your decision. Our many partners are always developing new modules. Choose one to meet your unique needs, change one when your needs evolve or use the Hardware Development Kit to make your own. Shipping and Warehousing FEaturES & BENEFITS The mobile workhorse The mobile worker is our focus CASE STUDY The WORKABOUT PRO is relied on every WORKABOUT PRO’s Natural Task day in mobile-intensive applications Support™ means mobile workers get the such as asset tracking, meter reading, job done faster and more comfortably, and mobile ticketing across a variety of even over the longest shifts. -

Psion Workabout Pro Instruction Manual Using Select Sheepware

PPSSIIOONN WWOORRKKAABBOOUUTT PPRROO IINNSSTTRRUUCCTTIIOONN MMAANNUUAALL UUSSIINNGG Contents Page The Psion WorkAbout Pro EID Reader 3 Psion WorkAbout Pro Buttons/Controls (G1/G3) 4/5 Turning Bluetooth On/Off 6 Setting Date and Time 5 Key Controller Program 7 Select Sheepware Pocket Edition Introduction 11 Animal Details 13 Breeding 15 Service, Scanning 15 Weaning 16 Flock Register 17 Add Animal/Retag 17 Births 19 Purchases, Sale/Death 20 Lost, Temporary Movement 21 Management 22 Comment, Condition Score, Hand Reared 22 Tick, Weighing 23 Health/Feeding 24 Health Treatment (single/multiple) 24 Drug Purchase, Feed Purchase 25 Group Events 26 Create/Edit Groups 26 Add/Remove from groups 27 View Groups Report 28 Record Group Events 29 Reports 30 Flock Report, Weights Report 30 Condition Score Report, Cull Report, Due to Report 31 Bluetooth Weighing 32 Setting up Psion for Bluetooth Weighing 33 Weighing in Select Sheepware with Bluetooth weigher 35 Synchronising with Select Sheepware 36 Guide to using TGM Remote Control Support – Team Viewer 38 Contact Us 40 2 The Psion WorkAbout Pro Electronic Tag Reader and PDA The Psion WorkAbout Pro is an easy to use handheld, robust, Electronic Tag reader with Windows Mobile Operating System, designed for use in harsh environments. It can withstand multiple 1.2m drops to concrete, dust and rain. As well as reading EID Tags, it can also be simultaneously linked to a Weigh Scale using Bluetooth for rapid weighing of groups of animals, or to a Portable Printer for printing EID Tag lists. TGM Software Solutions Select Sheepware program runs on the Psion, giving the user instant access to animal records and the ability to record management events. -

A Comparative Analysis of Mobile Operating Systems Rina

International Journal of Computer Sciences and Engineering Open Access Research Paper Vol.-6, Issue-12, Dec 2018 E-ISSN: 2347-2693 A Comparative Analysis of mobile Operating Systems Rina Dept of IT, GGDSD College, Chandigarh ,India *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Available online at: www.ijcseonline.org Accepted: 09/Dec/2018, Published: 31/Dec/2018 Abstract: The paper is based on the review of several research studies carried out on different mobile operating systems. A mobile operating system (or mobile OS) is an operating system for phones, tablets, smart watches, or other mobile devices which acts as an interface between users and mobiles. The use of mobile devices in our life is ever increasing. Nowadays everyone is using mobile phones from a lay man to businessmen to fulfill their basic requirements of life. We cannot even imagine our life without mobile phones. Therefore, it becomes very difficult for the mobile industries to provide best features and easy to use interface to its customer. Due to rapid advancement of the technology, the mobile industry is also continuously growing. The paper attempts to give a comparative study of operating systems used in mobile phones on the basis of their features, user interface and many more factors. Keywords: Mobile Operating system, iOS, Android, Smartphone, Windows. I. INTRUDUCTION concludes research work with future use of mobile technology. Mobile operating system is the interface between user and mobile phones to communicate and it provides many more II. HISTORY features which is essential to run mobile devices. It manages all the resources to be used in an efficient way and provides The term smart phone was first described by the company a user friendly interface to the users. -

P Palmtop Aper

u.s. $7.95 Publisher's Message ................................ , Letters to the Editor .................................. ~ - E New Third Party Ln Products and Services ............................ .E ..... =Q) HP Palmtop Users Groups ...................... J E :::J User to User ............................................ 1( :z Hal reports on the excitement at the HP Handheld - P Palmtop User's Conference, a new book by David Packard "<t" describing the history of HP, our new 200LXI1000CX Q) loaner p'rogram for developers, the 1995/1996 E Subscnbers PowerDisk and some good software :::J that didn't make it into thePowerDisk, but is on this o issue's ON DISK and CompuServe. > aper PalmtoD Wisdom .................................... 2< Know ~here you stand with your finances; Keep impqrtant information with you, and keep it secure; The best quotes may not tie in the quotes books. Built·in Apps on Vacation: To Africa and Back with the HP Palmtop ....................................... 1E acafTen/ The HP 200LX lielps a couple from Maryland prepare for their dream vacation to Africa. Built·in Apps on Vacation: Editor on Vacation .................................. 2( Even on vacation, Rich Hall, managing editor for The HP Palmtop Paper, finds the Palmtop to be an indispensable companion. AP~ointment Book: ~n ~~l~epP~~'~~~~~~.~~.~~...................... 2~ Appointment Book provides basic prol'ect management already built into the HP Pa mtop. DataBase: Print Your Database in the Format You Want .......................... 3( Create a custom database and print Hout in the for mat you want using the built-in DataBase program and Smart Clip. Lotus 1·2·3 Column: Basic Training for 1-2-3 Users ............... 3~ Attention first-time Lotus users, or those needing a bH of a refresher - get out your HP Palmtop and fonow along with this review of the basics. -

NEO Is Small. Very Small. but It Takes No Prisoners. Retail. Postal And

NEO Pocket Power psionteklogix.com NEO is small. Very small. But it takes no prisoners. Retail. Postal and Courier. Warehousing and Distribution. Supply chain. Arenas and sports venues. NEO plays a key role in them all, every day. And they love it. Is NEO the most compact, intelligent, rugged handheld computer around? Quite possibly... www.psionteklogix.com NEO Power To Your Pocket POCKET DYNAMO You need smaller, lighter data collection tools. But you won’t compromise on power or functionality. Now you don’t have to. NEO proves that exceptionally good Queue Busting things come in small packages. Its compact size (it weighs just over 275 g) coupled with a raft of features makes it perfect for the mobile workforce. The pocket dynamo is setting industry alight. Stock checking. Inventory tracking. Light warehouse duty or full-on, in-store retail. NEO takes them all on. You want some? Asset Tracking FEATURES & BenefITS It Doesn’t Mess Around And just feel the weight. Or lack of it. The NEO may be small but don’t be fooled. stylish NEO tips the scales at under 10oz. It’s unbelievably rugged. Which means it’s never out of action. And productivity We Can’t Stop Cramming never dips. You wanted it, so we’ve given it to you. NEO is Windows®-based and integrates This lean machine can withstand being with loads of advanced data capture and dropped from 4 feet to polished concrete. communications functions. WLAN and Merchandising Twenty-six times over (it could take more). Bluetooth® connectivity – check. VoIP, IM It packs an IP rating of 54, so you don’t and texting functionality, so you’re never have to worry about dust or moisture. -

The Symbian OS Architecture Sourcebook

The Symbian OS Architecture Sourcebook The Symbian OS Architecture Sourcebook Design and Evolution of a Mobile Phone OS By Ben Morris Reviewed by Chris Davies, Warren Day, Martin de Jode, Roy Hayun, Simon Higginson, Mark Jacobs, Andrew Langstaff, David Mery, Matthew O’Donnell, Kal Patel, Dominic Pinkman, Alan Robinson, Matthew Reynolds, Mark Shackman, Jo Stichbury, Jan van Bergen Symbian Press Head of Symbian Press Freddie Gjertsen Managing Editor Satu McNabb Copyright 2007 Symbian Software, Ltd John Wiley & Sons, Ltd The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (+44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (+44) 1243 770620. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

Wearable Technology for Enhanced Security

Communications on Applied Electronics (CAE) – ISSN : 2394-4714 Foundation of Computer Science FCS, New York, USA Volume 5 – No.10, September 2016 – www.caeaccess.org Wearable Technology for Enhanced Security Agbaje M. Olugbenga, PhD Babcock University Department of Computer Science Ogun State, Nigeria ABSTRACT Sproutling. Watches like the Apple Watch, and jewelry such Wearable's comprise of sensors and have computational as Cuff and Ringly. ability. Gadgets such as wristwatches, pens, and glasses with Taking a look at the history of computer generations up to the installed cameras are now available at cheap prices for user to present, we could divide it into three main types: mainframe purchase to monitor or securing themselves. Nigerian faced computing, personal computing, and ubiquitous or pervasive with several kidnapping in schools, homes and abduction for computing[4]. The various divisions is based on the number ransomed collection and other unlawful acts necessitate these of computers per users. The mainframe computing describes reviews. The success of the wearable technology in medical one large computer connected to many users and the second, uses prompted the research into application into security uses. personal computing, as one computer per person while the The method of research is the use of case studies and literature term ubiquitous computing however, was used in 1991 by search. This paper takes a look at the possible applications of Paul Weiser. Weiser depicted a world full of embedded the wearable technology to combat the cases of abduction and sensing technologies to streamline and improve life [5]. kidnapping in Nigeria. Nigeria faced with several kidnapping in schools and homes General Terms are in dire need for solution. -

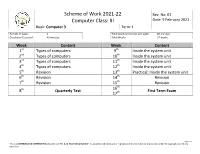

Scheme of Work 2021-22 Computer Class

Scheme of Work 2021-22 Rev. No: 01 Computer Class: III Date: 9 February 2021 Book: Computer 3 Term: I Periods of week: 2 Total teaching minutes per week: 80 minutes Duration of 1 period: 40 minutes Total Weeks: 17 weeks Week Content Week Content 1st Types of computers 9th Inside the system unit nd th 2 Types of computers 10 Inside the system unit rd th 3 Types of computers 11 Inside the system unit th th 4 Types of computers 12 Inside the system unit 5th Revision 13th Practical: Inside the system unit th th 6 Revision 14 Revision th th 7 Revision 15 Revision 16th 8th Quarterly Test First Term Exam 17th Page 1 of 5 This is a CONTROLLED & CONFIDENTIAL document of “Dr. A. Q. Khan School System”. Its unauthorized disclosure or reproduction shall be liable for prosecution under the copyright act and any other law Daily Lesson Plan (DLP) Session 2021-22 Subject: Computer Term – I Topic: Types of computer Class: III Week: 01 Learning Plan (Methodology) Time Resources Assessment Objectives By the end of this Introduction: Teacher should ask some question related to 40 Book Teacher should Lesson Students computer. min Board assess students by should be able to: Development: computer asking of: After reading the lesson teacher should tell them about four different Tell or explain main types of computer. questions about 1. Micro computer: These are most smallest and common computer computers. It is also called personal computer. These are types used in homes, school and colleges etc. these computers are divided into three types. -

Mobile Computing with Python

Mobile Computing with Python James “Wez” Weatherall & David Scott, Laboratory for Communications Engineering, Cambridge, England, {jnw22, djs55}@eng.cam.ac.uk Abstract This paper describes MoPy, a port of the Python 1.5.2 interpreter to the Psion 5/Epoc32 platform and Koala, a CORBA-style Object Request and Event Broker implemented natively in Python. While primarily a direct POSIX-based port of the standard Python interpreter, MoPy also adds thread, socket and serial support for the Psion platform. The Koala ORB is designed particularly with MoPy in mind and aims to support interoperation of devices over the low-power Prototype Em- bedded Network. The low-power requirements of PEN impose severe bandwidth and latency penalties to which conventional RPC technologies are not typically well suited. 1 Introduction Recent advances in wireless communications and embedded processor technology have paved the way for tetherless, intelligent embedded devices to enter into everyday use. Already technologies such as BlueTooth[2] and WAP[19] enable users to read their email, browse the web and link their various computational devices without physical network connections. This paper describes some key features of Koala, an Object Request and Event Broker written natively in Python and designed for use on handheld and wireless devices, and MoPy (Mobile Python), a Python interpreter for the Psion 5 Series[14]. The PEN project[1] at AT&T Laboratories Cambridge explores the future possibil- ities of embedded low-power wireless communications support in both conventional computer equipment and everyday appliances, with a view to providing totally ubiq- uitous interaction between devices. The prototype units use the 418MHz band and provide 24kbps throughput over a 5 metre radius, with power management allowing a unit to operate for several years on a single cell, subject to environmental conditions.