Archie Bunker As Working-Class Icon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luis Alberto Urrea Discusses 'The House of Broken Angels'

Luis Alberto Urrea discusses 'The House of Broken Angels' [00:00:05] Welcome to The Seattle Public Library’s podcasts of author readings and library events. Library podcasts are brought to you by The Seattle Public Library and Foundation. To learn more about our programs and podcasts, visit our web site at w w w dot SPL dot org. To learn how you can help the library foundation support The Seattle Public Library go to foundation dot SPL dot org [00:00:37] Hello. Good evening thank you for coming out tonight. [00:00:44] My name is mishit stone and I'm a reader services librarian here at the central library and I want to thank you for coming out tonight to hear Luis Alberto Urrea speak. This event is sponsored by the Seattle Public Library Foundation. Thank you to those who donate and support to the library authors series. Gary Kunis and media sponsored the Seattle Times and presented in partnership with Elliott Bay Book Company. Tonight we are here to celebrate a new novel by Luis Alberto Eurya. The House of Broken Flowers. I'm not doing the formal introduction but I just have to share that I loved loved loved this novel and Seattle shows up just CNO in The New York Times review that just came out via Taan when I said this all complicated all compelling and Urias powerful rendering of a Mexican American family that is also an American family. And what is your Raya's novel. But a Mexican American novel that is also an American novel. -

2020-2021 Arizona Hunting Regulations

Arizona Game and Fish Department 2020-2021 Arizona Hunting Regulations This publication includes the annual regulations for statewide hunting of deer, fall turkey, fall javelina, bighorn sheep, fall bison, fall bear, mountain lion, small game and other huntable wildlife. The hunt permit application deadline is Tuesday, June 9, 2020, at 11:59 p.m. Arizona time. Purchase Arizona hunting licenses and apply for the draw online at azgfd.gov. Report wildlife violations, call: 800-352-0700 Two other annual hunt draw booklets are published for the spring big game hunts and elk and pronghorn hunts. i Unforgettable Adventures. Feel-Good Savings. Heed the call of adventure with great insurance coverage. 15 minutes could save you 15% or more on motorcycle insurance. geico.com | 1-800-442-9253 | Local Office Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Motorcycle and ATV coverages are underwritten by GEICO Indemnity Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2019 GEICO ii ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT — AZGFD.GOV AdPages2019.indd 4 4/20/2020 11:49:25 AM AdPages2019.indd 5 2020-2021 ARIZONA HUNTING4/20/2020 REGULATIONS 11:50:24 AM 1 Arizona Game and Fish Department Key Contacts MAIN NUMBER: 602-942-3000 Choose 1 for known extension or name Choose 2 for draw, bonus points, and hunting and fishing license information Choose 3 for watercraft Choose 4 for regional -

Juliet Ouyoung 917-528-9764

Feb. 2015 Page #1 of 2 Juliet Ouyoung 917-528-9764 www.jouyoung.com Costume Designer Assistant Costume Designer The Shanghai Hotel 2006 Late Show With David Letterman 2006-2015 Feature / Cornucopia Productions Talk –Variety TV Show \ CBS – Worldwide Pants INC. 2006 Contemporary Drama/ Human Trafficking Fast Paste Sketch Characters \ Comedy Hill Harper, Pei Pei Cheng, Eugenia Yuan Bruce Willis, Steve Martin, Martin Short, Bill Murray,Chris Elliott Jerry Davis, Director Jerry Foley , Director ; Sue Hum, CD Neurotica 2000 Bernard & Doris 2005 Feature / Three Forks Productions Feature / Trigger Street Productions 2000 Contemporary Comedy / Road Trip 1980’s-1990’s Drama / Doris Duke Biopic Brian D’Arcy James, Amy Sedaris Ralph Fiennes, Susan Sarandon Roger Rawlings, Director Bob Balaban, Director ; Joe Aulissi, CD Mob Queen 1997 Copshop 2003 Feature / Etoile Productions Pilot / PBS Television 1956 Comedy / Mafia Meets Transvestite 2003 Contemporary Drama / NYPD - Brothel Tony Sirico, David Proval, Candice Kane Richard Dreyfuss, Rosey Perez, Rita Moreno, Blair Brown Jon Carnoy, Director Anita Addison & Joe Cacaci , director ; Bobby Tilly, CD Harwood 1999 Like Mother Like Son 2002 Feature / Absolutely Legitimate Film MOW / CBS Televison 1999 Contemporary / Sci-fi Thriller 1998 Contemporary Drama / Sente Kimes’ Story Morgan Roberts, Director Mary Tyler Moore, Jean Stapleton Arthur Seidelman, Director; Martin Pakledinaz, CD The Floys Of Neighborly Lane 1998 Deconstructing Harry 1996 Short / Once Upon A Picture Production Feature / Sweetheart Productions -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

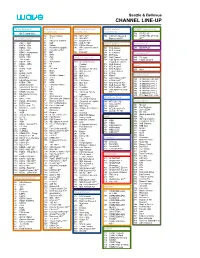

Channel Lineup

Seattle & Bellevue CHANNEL LINEUP TV On Demand* Expanded Content* Expanded Content* Digital Variety* STARZ* (continued) (continued) (continued) (continued) 1 On Demand Menu 716 STARZ HD** 50 Travel Channel 774 MTV HD** 791 Hallmark Movies & 720 STARZ Kids & Family Local Broadcast* 51 TLC 775 VH1 HD** Mysteries HD** HD** 52 Discovery Channel 777 Oxygen HD** 2 CBUT CBC 53 A&E 778 AXS TV HD** Digital Sports* MOVIEPLEX* 3 KWPX ION 54 History 779 HDNet Movies** 4 KOMO ABC 55 National Geographic 782 NBC Sports Network 501 FCS Atlantic 450 MOVIEPLEX 5 KING NBC 56 Comedy Central HD** 502 FCS Central 6 KONG Independent 57 BET 784 FXX HD** 503 FCS Pacific International* 7 KIRO CBS 58 Spike 505 ESPNews 8 KCTS PBS 59 Syfy Digital Favorites* 507 Golf Channel 335 TV Japan 9 TV Listings 60 TBS 508 CBS Sports Network 339 Filipino Channel 10 KSTW CW 62 Nickelodeon 200 American Heroes Expanded Content 11 KZJO JOEtv 63 FX Channel 511 MLB Network Here!* 12 HSN 64 E! 201 Science 513 NFL Network 65 TV Land 13 KCPQ FOX 203 Destination America 514 NFL RedZone 460 Here! 14 QVC 66 Bravo 205 BBC America 515 Tennis Channel 15 KVOS MeTV 67 TCM 206 MTV2 516 ESPNU 17 EVINE Live 68 Weather Channel 207 BET Jams 517 HRTV PayPerView* 18 KCTS Plus 69 TruTV 208 Tr3s 738 Golf Channel HD** 800 IN DEMAND HD PPV 19 Educational Access 70 GSN 209 CMT Music 743 ESPNU HD** 801 IN DEMAND PPV 1 20 KTBW TBN 71 OWN 210 BET Soul 749 NFL Network HD** 802 IN DEMAND PPV 2 21 Seattle Channel 72 Cooking Channel 211 Nick Jr. -

Beaver News, 50(18)

astic from and arry abed March 30 1976 Voume No 18 were ams ite Council announces Leres John Linnell underi the tweIvehour Big goes will thIy courses nder By Elaine Maiperson By Lotsa Morals The Graduate Council has an- the full time to explore all Dr John Linnell Dean of the new schedule for 300 and ramifications of an idea College recently announced his %el to into effect at courses go Mr Stewart registrar com intentions to aid Dr Edward Gates College in the fall of 1976 President of the in his at- mented Im excited about the way College ath course will be offered once to Beavers the new plan opens up the schedule tempt improve security for of twelve single period We will certainly have fewer con system Beaver security is from to This flicts next year Fhe graduate average just average merely will the to plan help college students like to consolidate then average Dean Linnell commented efficient of more use But we have to take look at what class time by making fewer trips to assroom space and of faculty time we arc and where were and the campus The new schedule will going Under the new instructors make system attract more graduate students As decision based upon how it II be able to teach at least four will affect the see it the only problem will be the entire College corn- aduate courses over and above weathcr One snow closing will munity Lr normal load of three un block out month of classes Dean Linnell has de ided that yrgrduat courses Now well be radically hargrg Bcavcr Litsa Marlos senior English to teach seven courses each security -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

A Decade of Deceit How TV Content Ratings Have Failed Families EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Major Findings

A Decade of Deceit How TV Content Ratings Have Failed Families EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Major Findings: In its recent report to Congress on the accuracy of • Programs rated TV-PG contained on average the TV ratings and effectiveness of oversight, the 28% more violence and 43.5% more Federal Communications Commission noted that the profanity in 2017-18 than in 2007-08. system has not changed in over 20 years. • Profanity on PG-rated shows included suck/ Indeed, it has not, but content has, and the TV blow, screw, hell/damn, ass/asshole, bitch, ratings fail to reflect “content creep,” (that is, an bastard, piss, bleeped s—t, bleeped f—k. increase in offensive content in programs with The 2017-18 season added “dick” and “prick” a given rating as compared to similarly-rated to the PG-rated lexicon. programs a decade or more ago). Networks are packing substantially more profanity and violence into youth-rated shows than they did a decade ago; • Violence on PG-rated shows included use but that increase in adult-themed content has not of guns and bladed weapons, depictions affected the age-based ratings the networks apply. of fighting, blood and death and scenes We found that on shows rated TV-PG, there was a of decapitation or dismemberment; The 28% increase in violence; and a 44% increase in only form of violence unique to TV-14 rated profanity over a ten-year period. There was also a programming was depictions of torture. more than twice as much violence on shows rated TV-14 in the 2017-18 television season than in the • Programs rated TV-14 contained on average 2007-08 season, both in per-episode averages and 84% more violence per episode in 2017-18 in absolute terms. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Gender and Parenting: a Content Analysis of the American Sitcom Mollie Borer Concordia University, Saint Paul

Concordia Journal of Communication Research Volume 5 Article 2 6-1-2018 Gender and Parenting: A Content Analysis of the American Sitcom Mollie Borer Concordia University, Saint Paul Nicholas Alexander Concordia University, Saint Paul Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csp.edu/comjournal Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Borer, Mollie and Alexander, Nicholas (2018) "Gender and Parenting: A Content Analysis of the American Sitcom," Concordia Journal of Communication Research: Vol. 5 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csp.edu/comjournal/vol5/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Concordia Journal of Communication Research by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RUNNING HEAD: BorerGender and Alexander: and Parenting: Gender and Parenting:A Content A Content Analysis Analysis of of the American American Sitcom Sitcom Gender and Parenting A Content Analysis of the American Sitcom Mollie Borer and Nicholas Alexander Concordia University, St. Paul MN 12/14/2017 Published by DigitalCommons@CSP, 2018 1 Gender and Parenting: A ContentConcordia Journal Analysis of Communication of the American Research, Vol. Sitcom 5 [2018], Art. 2 1 Abstract The purpose of this study was not only to get a better understanding of what types of gender and parenting norms exist in television sitcoms, but to see if the same gender and parenting norms that were displayed in the 20th century, would be displayed in a sitcom created 30 years later. -

The Norman Conquest: the Style and Legacy of All in the Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Boston University Institutional Repository (OpenBU) Boston University OpenBU http://open.bu.edu Theses & Dissertations Boston University Theses & Dissertations 2016 The Norman conquest: the style and legacy of All in the Family https://hdl.handle.net/2144/17119 Boston University BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION Thesis THE NORMAN CONQUEST: THE STYLE AND LEGACY OF ALL IN THE FAMILY by BAILEY FRANCES LIZOTTE B.A., Emerson College, 2013 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts 2016 © 2016 by BAILEY FRANCES LIZOTTE All rights reserved Approved by First Reader ___________________________________________________ Deborah L. Jaramillo, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Film and Television Second Reader ___________________________________________________ Michael Loman Professor of Television DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Jean Lizotte, Nicholas Clark, and Alvin Delpino. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I’m exceedingly thankful for the guidance and patience of my thesis advisor, Dr. Deborah Jaramillo, whose investment and dedication to this project allowed me to explore a topic close to my heart. I am also grateful for the guidance of my second reader, Michael Loman, whose professional experience and insight proved invaluable to my work. Additionally, I am indebted to all of the professors in the Film and Television Studies program who have facilitated my growth as a viewer and a scholar, especially Ray Carney, Charles Warren, Roy Grundmann, and John Bernstein. Thank you to David Kociemba, whose advice and encouragement has been greatly appreciated throughout this entire process. A special thank you to my fellow graduate students, especially Sarah Crane, Dani Franco, Jess Lajoie, Victoria Quamme, and Sophie Summergrad.