Every Culture Is Internally Plural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2007 VOLUME I.A / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2007, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 51.500 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

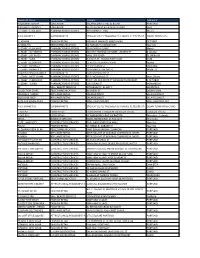

Merchant Name Business Type Address Address 2 NAZEEM

Merchant Name Business Type Address Address 2 NAZEEM BUTCHERY EDUCATION SALAH ELDIN ST AND EL BAZAR PORTSAID BRILLIANCE SCHOOLS EDUCATION KILLO 26 CAIRO ALEX DESERT ROAD GIZA EL EZABY - ELSALAM E PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 516 KORNISH ELNILE Maadi ALFA MARKET 1 SUPERMARKETS ETISALAT CO. EL TAGAMOA EL KHAMES -ELTESEEN ST DOWN TOWN BLD., EL ADHAM FASHION RETAIL MEHWAR MARKAZY ABAZIA MALL OCTOBER ELHANA TEL TELECOMMUNICATION 12 HASSAN EL MAMOUN ST. Nasr city EL EZABY - ELSALAM E PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 516 KORNISH ELNILE Maadi EL EZABY - OCTOBER U PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 283 HAY 7 BEHIND OCTOBER UNIVERCITY 6 October EL EZABY - SKY PLAZA PHARMACY/DRUG STORES MALL SKY PLAZA EL SHEROUK EL EZABY - SUEZ PHARMACY/DRUG STORES ELGALAA ST, ASWAN INSTITUION SUEZ EL EZABY - ELDARAISA PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 11 KILO15 ALEX-MATROUH Agamy EL EZABY- SHOBRA 2 PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 113 SHOUBRA ST. SHOUBRA EL EZABY- ZAMALEK 2 PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 6A ELMALEK ELAFDAL ST. ZAMALEK KHAYRAT ZAMAN MARKET SUPERMARKETS HATEM ROUSHDY ST EL EZABY - MEET GHAM PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 37 ELMOQAWQS ST Meet Ghamr EL EZABY - ELMEHWAR PHARMACY/DRUG STORES PIECE 101,3RD DISTRICT,MEHWAR ELMARKAZY 6 OCTOBER EL EZABY - SUDAN PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 166 SUDAN ST. MOHANDSIN EV SPA / BEAUTY SERVICES 278 HEGAZ ST. EL HAY 7 HELIOPOLIS COLLECTION STARS TELECOMMUNICATION 39 SHERIF ST. DOWNTOWN SAMSUNG ASWAN APPLIANCE RETAIL SALAH ELDIN ST SALAH ELDIN ST GOLD LINE SHOP APPLIANCE RETAIL SALAH ELDIN ST SALAH ELDIN ST ELITE FOR SHOES ASWA FASHION RETAIL MALL ASWAN PLAZA MALL ASWAN PLAZA ALFA MARKET S3 SUPERMARKETS ETISALAT CO. EL TAGAMOA EL KHAMES -ELTESEEN ST- DOWN TOWN-NEW CAIRO ELSHEIBY FOOD RETAIL 124 MASR WEL SUDAN ST.HADDayek El koba Haddayek El koba ELSHEIBY 2 FOOD RETAIL 67 SAKR KORICH BLD.SHERATTON Sheratton - Helipolis SIR KIL BUSINESS SERVICES 328 EL NARGES BLD. -

Day Case Surgeries El Basateen Hospital Cairo 500 St

EGYPT PROVIDER NETWORK CALL CENTER NO. +974 800 2000 Provider Name Provider Type City Address Tel Day Case Surgeries El Basateen Hospital Cairo 500 St. - Kuwait Buildings - beside Red Crescent School GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 Tabarak Hospital - Saft El Laban Hospital Cairo Tereet Abdel Aal Street With El Eshreen St. GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 Tabarak Hospital - Omraneya Hospital Cairo El Thalatheen Street - Behind Sayed Darwish GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 Dar El Oyoun Hospital - Saft El Laban Hospital Cairo El Moaatasem Bellah St. - El Tahrir St. GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 Dar El Teb Hospital Hospital Cairo Oman St. GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 Eye and Laser World Hospital - Dokki Hospital Cairo El Tahrir St. - El Behoos Metro Station GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 Misr International Hospital Hospital Cairo Adel Hussein Rostom St. (El Saraya previously) GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 El Katib Hospital Hospital Cairo Abdallah El Katib St. - Veny Sq. GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 El Shabraweshy Hospital Hospital Cairo Vini Square GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 El Rowad Hospital - Dokki Hospital Cairo Iran St. - from El Tahrir St. - Behind Asd Ibn El Forat mosque GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 International Eye Hospital - Children Eye Branch Hospital Cairo Adel Hussien Rostom St. - Off Fini Square GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 Al-Hayat Eye Center Hospital Cairo Abd El Aziz Selim St. - from El Thawra St. - Beside Shooting Club GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 El Kawkab Hospital Hospital Cairo Doctor Al Saloly St. - Al Mesaha sq. GlobeMed (+202) 330 86 252 Dar El Oyoun Hospital - Main Branch Hospital Cairo El Ghazaly St. -

Televising Egypt's History

The Cairo Review Interview Televising Egypt’s History Egyptian screenwriter Waheed Hamed discusses the state of Egyptian cinema, Islamism in his work, and the shrinking space for creativity in Egypt Waheed hamed is a self-proclaimed anti-radical. The widely acclaimed screenwriter has fo- cused his five-decade career almost entirely on fighting the rising tide of Islamic fundamental- ism in Egypt. In June 2017, the second season of the television serial Al-Gamaa (“The brother- hood”)—which traces the evolution of the Muslim brotherhood from the death of its founder hassan El-banna through the late 1960s—ignited controversy for portraying Gamal Abdel nasser as a member of the now-banned Islamist group. Rather, hamed’s true intentions, he clarified in a beleaguered TV appearance, were to denounce the brotherhood’s actions and reveal “the truth about them and the poison they injected in society.” Raised in Sharqiya, Lower Egypt, hamed, 74, is the son of illiterate farmers. he started writing short stories in 1960s Cairo before switching to radio dramas upon the advice of novelist yusuf Idris, who took notice of hamed’s dramatic flair. his cinematic career took off shortly after one of his radio dramas highlighting Egypt’s flawed criminal justice system, Sad Night Bird, was turned into a hit movie. Since then, he has written more than seventy films, TV serials, radio dramas, and plays. his 1992 black comedy Terrorism and Kebab became a cultural landmark of the Mubarak era, portraying one man’s hapless battle against Egypt’s corrupt bureaucracy and poking fun at the government’s inability to deal with terrorism. -

Ahmed Zaki and the Politics of Visual Resistance

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 The Willfulness of a Missing Frame: Ahmed Zaki and the Politics of Visual Resistance Miriam M. Gabriel City University of New York Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2096 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE WILLFULNESS OF A MISSING FRAME: AHMED ZAKI AND THE POLITICS OF VISUAL RESISTANCE by MIRIAM GABRIEL A master’s thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in the Middle Eastern Studies Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of the Master of Arts, the City University of New York 2017 © 2017 MIRIAM GABRIEL All Rights Reserved ii The Willfulness of a Missing Frame: Ahmed Zaki and the Politics of Visual Resistance by Miriam Gabriel This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in the Middle Eastern Studies Program in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Approved by Date Christopher Stone Thesis Advisor Date Beth Baron Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Willfulness of a Missing Frame: Ahmed Zaki and the Politics of Visual Resistance by Miriam Gabriel Advisor: Christopher Stone Ahmed Zaki (1949-2005) is one of Egyptian cinema’s most prominent leading actors, with work spanning three decades of critical films that informed a generation’s visual register of masculinity.