NOTES Archaeological Work in Oxford, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cropredy Bridge by MISS M

Cropredy Bridge By MISS M. R. TOYNBEE and J. J. LEEMING I IE bridge over the River Chenveff at Cropredy was rebuilt by the Oxford shire County Council in J937. The structure standing at that time was for T the most part comparatively modern, for the bridge, as will be explained later, has been thoroughly altered and reconstructed at least twice (in J780 and 1886) within the last 160 years. The historical associations of the bridge, especiaffy during the Civil War period, have rendered it famous, and an object of pilgrimage, and it seems there fore suitable, on the occasion of its reconstruction, to collect together such details as are known about its origin and history, and to add to them a short account of the Civil War battle of 1644, the historical occurrence for which the site is chiefly famous. The general history of the bridge, and the account of the battle, have been written by Miss Toynbee; the account of the 1937 reconstruction is by Mr. Leeming, who, as engineer on the staff of the Oxfordshire County Council, was in charge of the work. HISTORY OF TIlE BRIDGE' The first record of the existence of a bridge at Cropredy dates, so far as it has been possible to discover, from the year 1312. That there was a bridge in existence before 1312 appears to be pretty certain. Cropredy was a place of some importance in the :\1iddle Ages. It formed part of the possessions of the See of Lincoln, and is entered in Domesday Book as such. 'The Bishop of Lincoln holds Cropelie. -

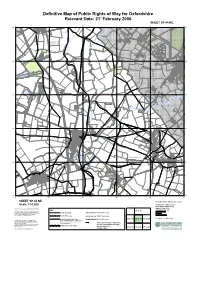

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 44 NE

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 44 NE 45 46 47 48 49 50 Church View Douglas Farm 50 MANOR PARK 170/1 50 170/6 Canal Feeder Rozel CLAYDON 170/5 Manor Farm Vicarage Pond 170/4 Pond BIGNOLDS CLOSE Hillside House Drain Pond Priory Cott Priors Mead Clattercote House Astell Farm House Hilltop Cottage NGTON ROAD LI MOL Pond 170/2 Appletree Cottages Pond Appletree Lodge Appletree Appletree House Appletree Farm Pond Pond Claydon with Russet House Clattercot CP Oxford Canal 170/1 Highfurlong Brook Appletree Industrial Estate Appletree Industrial A 361 Estate Brookside House 323/1a Pond Pond ROAD BYEFIELD Clattercote Priory and remains of 8920 (Gilbertine founded 1148-66) Pond Churchlands Tel Ex Cottage The Bungalow 170/4 Clattercote Clattercote Cottages Churchlands Cottages Chipping Warden Primary School Lake Manor Farm 170/6 Highfield Fish Pond Pond LONG BARROW Pond Pond A 361 179/5 49 A 361 49 Overflow THE CLOSE 323/1a BYFIELD ROAD 179/13 APPLETREE ROAD CULWORTH ROAD Rose and Crown 170/2 Drain NORTHAMPTONSHIRENORTHAMPTONSHIRE ORCHARD Pond ALLENS St Peter and St Paul's Church BANBURY ROAD Forge Farm END Pond Oxford Canal HOGG Issues Issues Highfurlong Brook 5356 CLAYDON ROAD Drain Clattercote Reservoir MILL LANE 179/3 Pond 323/1a Drain Oathill Farm ARBURY BANKS Drain Drain Issues 393/2 Cropredy Lawn Issues 179/13 Drain Cropedy Lawn Bungalow Drain Drain Drain 393/1 Overflow Rectory Farm 179/5 Issues Lake Oxford Canal Pond /1 Pond Prescote CP 393 Lambert's Barn A 361 Drain -

Small Unit 1 Particulars, Prescote Manor Farm

COMMERCIAL fishergerman.co.uk TO LET Unit 1, Prescote Manor Farm Business Park, Cropredy, Banbury, Oxfordshire OX17 1PF Rent Guide Price From £2,400 Per Annum • Rural Location • Office/Studio Unit • Ample Car Parking • Established Business Location Approximate Distances: Viewings and Further Information: • Cropredy - 0.5 miles. • Banbury - 4 miles. • Daventry - 4 miles. Simon Patrick • M40 (Junction 11) - 4 miles. [email protected] 01295 226283 07887 594684 Unit 1, Prescote Manor Farm To Let Business Park, Cropredy, Banbury Description VAT The Business Park comprises a range of office and All prices are stated exclusive of VAT under the Finance light industrial units in a rural setting. One unit is Act 1989. Accordingly interested parties are advised to currently available as follows:- consult their professional advisors as to their liabilities, if any. Unit 1 comprises a recently refurbished studio/office space of 13.40 sq m (144.28 sq ft) featuring two double glazed windows and a kitchenette (with hot Viewing If you would like to view this property please contact our water tank). office to arrange a suitable date and time. Services Did You Know? Unit 1 has mains electricity and water connected. Fisher German can assist with all commercial property Telephone and broadband services are available matters, including sales and lettings, valuations, subject to connection with BT. schedules of condition, dilapidations, property management and rating. For further details please Electricity is metered via sub meters on site and is telephone 01295 226283. charged to the Tenants at cost basis. Location Water charges are included within the annual rent. -

Volume 15 Number 03

CAKE AND COCKHORSE BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Summer 2001 €2.50 Volume 15 Number 3 ISSN 6522-0823 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Registered Charity No 260581 President: The Lord Saye and Sele. Chairman: Brian Little, 12 Longfellow Road, Banbury OX 16 9LB (tel. 01295 264972). Cake and Cockhorse Editorial Committee J.P. Bowes, Jeremy Gibson (as below), Beryl Hudson Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: Simon Townsend, G.F. Griffiths, Banbury Museum, 39 Waller Drive, 8 Horsefair, Banbury, Banbury OX 16 OAA Oxon. OX 16 9NS; (tel 01295 259855)* (tel. 01295 263944) Programme Secretary: Hon. Research Adviser: R.N.J. Allen, J.S.W. Gibson, Barn End, Keyte's Close Harts Cottage, Adderbury, Church Hanborough, Banbury, Oxon OX 17 3PB Whey, Oxon. OX29 8AB, (tel. 01295 81 1087) (tel. 01993 882982). 'Although the Museum at 8 Horsefair closes at the cnd of September, this address and phone number will remain valid for correspondence and information until the new Museum opens in 2002 Committee Members: Mrs D. Hayter, Miss B.P Hudson, Miss K. Smith, Mrs F. Thompson Membership Secretary: Mrs Margaret Little, C/o Banbury Museum, 8 Horsefair, Banbury, Oxon. OX16 9LB. Details of the Society's activities and publications will be found inside the back cover. Cake and Cockhorse The magazine of the Banbury Historical Society, issued three times a year. Volume 15 Number Three Summer 2001 Banbury Museum - Present and Future ... ... 82 Sally Stradling Kimberley’s, Banbury Building Contractors ... 84 Pamela Keegan Cropredy Friendly Society ... ... ... 110 With this number of Cake & Cockhorse members will receive their annual invitation to our start-of-the-season Reception at Banbury Museum, as always encouraged by the Museum staff, our Secretary Simon Townsend, our unofficial voluntary public relations officer Chris Kelly, and all their colleagues. -

W Ell-Being • Community • Economy • Heritag E • G Ro

Cherwell Local Plan 2011 – 2031 (Part 2) Development Management Policies and Sites unity • Ec mm on o om • C y g • in H e e r -b i l t l a e g e W • • G r t o n w e t h m n • o S r u i s v ta En in t • abl ec e • Conn Issues Consultation January 2016 Cherwell Local Plan Part 2 - Development Management Policies and Sites: Issues Paper Cherwell Local Plan Part 2 - Development Management Policies and Sites: Issues Paper 1 Introduction 5 2 Background 9 3 Cherwell Context 11 4 Key Issues 15 4.1 Theme One: Developing a Sustainable Local Economy 15 4.1.1 Employment 15 4.1.2 Retail 24 4.1.3 Tourism 28 4.1.4 Transport 30 4.2 Theme Two: Building Sustainable Communities 38 4.2.1 Housing 38 4.2.2 Community Facilities 52 4.2.3 Open Space, Sport and Recreation Facilities 56 4.3 Theme Three: Ensuring Sustainable Development 61 4.3.1 Sustainable Construction and Renewable Energy 61 4.3.2 Protecting and Enhancing the Natural Environment 69 4.3.3 The Oxford Green Belt 80 4.3.4 Built and Historic Environment 85 4.3.5 Green Infrastructure 90 5 Key Issues: Cherwell's Places 93 5.1 Neighbourhood Planning 93 5.2 Bicester 94 5.3 Banbury 102 5.4 Kidlington 107 5.5 Villages & Rural Areas 113 5.6 Infrastructure 118 Cherwell Local Plan Part 2 - Development Management Policies and Sites: Issues Paper Cherwell Local Plan Part 2 - Development Management Policies and Sites: Issues Paper 6 Call for Sites 121 7 What Happens Next? 123 Appendices 1 Glossary 125 2 Summary of Representations Received to the Consultation on the Scope of Local Plan Part 2 (May 2015) 131 3 Local -

Oxfordshire Digital Infrastructure Strategy and Delivery Plan

Oxfordshire Digital Infrastructure Strategy and Delivery Plan JANUARY 2020 – V11 Bower, Craig – COMMUNITIES | [email protected] Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................. 2 Vision ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Superfast Broadband ............................................................................................................................ 6 Commercial Operators in Oxfordshire ........................................................................................... 6 BT Plc - Openreach ...................................................................................................................... 6 Virgin Media .................................................................................................................................. 6 Gigaclear Plc ................................................................................................................................. 7 Airband .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Hyperoptic ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Open Fibre Networks Ltd (OFNL) .............................................................................................. -

Cake & Cockhorse

CAKE & COCKHORSE BA4NBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 1982. PRICE f1.00 ISSN 0522-0823 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman: J. S.W. Gibson, Harts Cottage, Church Hanborough, Oxford. OX7 2AB. Magazine Editor: D. E. M. Fiennes, Woadmill Farm, Broughton, Banbury. OX15 6AR. Hon. Secretary: Acting Hon. Treasurer : Mrs N. M . Clifton, Miss Mary Stanton, Senendone House, 12 Kennedy House, Shenington, Banbury. Orchard Way, Banbury. (Tel: Edge Hill 262) (Tel: 57754) Hon. Membership Secretary: Records Series Editor: Mrs Sarah Gosling, J.S.W. Gibson, Banbury Museum, Harts Cottage, 8 Horsefair, Banbury. Church Hanborough, Oxford OX7 2AB. (Tel: 59855) (Tel: Freeland (0993)882982) Committee Members: Dr E. Asser, Miss C.G. Bloxham, Mrs G.W. Brinkworth, Mr N. Griffiths, Mr G. de C. Parmiter, Mr J.F. Roberts Details about the Society's activities and publications can be found on the inside back cover The cover illustration is from the brass of Lady Bishopston in Broughton Church. CAKE & COCKHORSE The Magazine of the Banbury Historical Society. Issued three times a year. Volume 8 Number 9 Summer 1982 - Pamela Keegan Cattleyards and Hovels in Cropredy, 1981 242 ' D.M. Rogers The 'Friends of North Newington'; A New Pynson Broadside. (Reprinted from the The Bodleian Library Record, Vol.V, No.5, May 1956, by kind permission of the Editor). 264 David Fiennes An Historic Cup 2 67 Sir William Bishopston (d1447) 269 The Cardinal's Daughter - a near miss for Banbury 272 Book Reviews 273 Annual Report and Accounts 2 74 It is warming to the heart to learn, from the second article in this issue, that in the year 1400 North Newington was brought to the attention of Pope Boniface D( (Pietro Tomacelli of Naples). -

Volume 06 Index

CAKE & COCKHORSE VOLUME FIVE NUMBERS 1 - 9 Autumn 1971 - kmmer 1974 VOLUME SIX NUMBERS 1 - 6 Autumn 1974 - Summsr 1976 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY c/o Banbury Mueeum. Banbury, Oxon. @ Banbury Historical Society, 1971-1976 .. .... .. , _c .,. , 1 '; *: *: . J Volume Five printed by Express Litho Service, Cowley, Oxford Volume Six printad by Techuicopy Ltd. , Stonehouse, Glos. ; Banbury Instant Printing, Banbury; and Parchment (chdord)Ltd. cms volume v Bary- The Pattern of Local Government, 1554-1835, Part 1 3 Banbury Wills in the Prerogative Court of Canterburg, 1701-1723 18 Banbury at the turn of the Century 23 A Chimney-Plece at Banbury? 43 Naming after Godparents 47 The Archaeological Implications of Redevelopment in Banbury 49 The Building and Furnishing of St. Marg’s Church 63 Banbury Marriages at Draytcm in 1790 78 Banbury - The Pattern of Local Governmeat, 1554-1835, Part 2 83 Kings suttaa Station 96 The Banbury Workhouse Child during the 1890s 103 Banbury Castle - A Summary of Excavations in 1972 109 Travellers’ Tales, Part 1 127 Travellers’ Tales, Part 2 143 WO&~~XWRWSUIC~, 1580-1644 167 Excavations at Baalrury Castle, 1973-74 An Interim Report 177 VdUlWM Tooley’s Boatyard 3 Shenington: The Village an the shlniag Hill 5 Aepeote of Iaba~ringLife: The Model Farm at Ditchley, 1856-73 13 Working the Cut - Reminiecences of a Boatman 19 James Sutton - A Presbyterian Preacher 30 Opem Village: Victorian Middle Bartar. 39 A Note on Sergean@ Tenure at south Newin%oa 48 The Plush Industry in Shutford 59 Relfgious Secte in 19th Century Banbury: Some New Evidence .7a A Disputed Inheritance 83 8hip Money Assessments (1636)and Rateable Values (1974) 88 &persbltioa and Witchcraft in the Nineteenth Century 89 The Estates of the Barony Saye and Sele in Pre-Rm1uti-q England 107 Tudor Inspiration in Broughtm Castle 122 bdex of Places and Subjecte, Vole. -

Bicester and Banbury Area Review Contracts to Commence June 2013

CMDDL13E Annex 1 Bicester and Banbury Area Review Contracts to commence June 2013 A: Services under review in Bicester and Banbury area BICESTER AREA SERVICES Service Contract Days of ITEM Route Operator Page number number operation A 22/23 C40 Bicester town services Mon – Sat Heyfordian 2 Oxford – Bicester and B 25/25A C49 Mon – Sat Heyfordian 3/4 Bicester – Woodstock via villages C 37 C40 Finmere - Bicester Tues/Weds Heyfordian 5 D 81 C30 Banbury – Bicester * Sat Heyfordian 6 E 81A C40 Somerton – Ardley – Bucknell – Bicester Tues/Weds Heyfordian 7 F 90 C31 Upper Heyford – Banbury Thurs OCC 8 Charlton G 94 C44 Bicester – Blackthorn – Oxford * Mon – Sat 9 Services H S5 C47 Oxford – Ambrosden late eve.* Fri – Sat Stagecoach 10 BANBURY AREA SERVICES I 488/489 C12 Chipping Norton - Banbury via Bloxham* Mon-Sat Stagecoach 11 Banbury: Easington, Bodicote & J B1/B2 C17 Mon-Sat Stagecoach 12 Cherwell Heights* B1/B2/ K C16 Banbury town services Sun & BH Stagecoach 13 B5/B8 L B5 C2 Banbury - Bretch Hill evenings* Daily Stagecoach 14 M B7/B10 C14 Banbury - Grimsbury & Hanwell Fields Mon-Sat Heyfordian 15 Oxford - Banbury via Middle Barton & C7: Mon-Sat C7/C8 Deddington* C8: Sun N S4 Stagecoach 16/17 C23 Route diversion to serve Kidlington Airport C23: Mon-Sat ‘County O n/a North Oxfordshire Dial-a-Ride Mon-Sat Centre Bus 18/19 Connect’ B: Services under review elsewhere P 47 V67 Ashbury – Swindon/Lambourn Mon-Sat Thamesdown 20 Q W1 n/a ‘Lewknor Taxibus’ Mon-Fri Go Ride 21 Goring Dial-a- R n/a n/a Goring Dial-a-Ride Thursday 22 Ride * Certain journeys only (see detailed service descriptions for clarification) Notes Parishes served: Where a parish is listed in [square brackets], the service passes through the parish but does not serve the main area of population. -

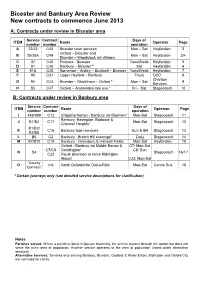

Bicester and Banbury Area Review New Contracts to Commence June 2013

Bicester and Banbury Area Review New contracts to commence June 2013 A: Contracts under review in Bicester area Service Contract Days of ITEM Route Operator Page number number operation A 22/23 C40 Bicester town services Mon – Sat Heyfordian 2 Oxford – Bicester and B 25/25A C49 Mon – Sat Heyfordian 3/4 Bicester – Woodstock via villages C 37 C40 Finmere - Bicester Tues/Weds Heyfordian 5 D 81 C30 Banbury – Bicester * Sat Heyfordian 6 E 81A C40 Somerton – Ardley – Bucknell – Bicester Tues/Weds Heyfordian 7 F 90 C31 Upper Heyford – Banbury Thurs OCC 8 Charlton G 94 C44 Bicester – Blackthorn – Oxford * Mon – Sat 9 Services H S5 C47 Oxford – Ambrosden late eve.* Fri – Sat Stagecoach 10 B: Contracts under review in Banbury area Service Contract Days of ITEM Route Operator Page number number operation I 488/489 C12 Chipping Norton - Banbury via Bloxham* Mon-Sat Stagecoach 11 Banbury: Easington, Bodicote & J B1/B2 C17 Mon-Sat Stagecoach 12 Cherwell Heights* B1/B2/ K C16 Banbury town services Sun & BH Stagecoach 13 B5/B8 L B5 C2 Banbury - Bretch Hill evenings* Daily Stagecoach 14 M B7/B10 C14 Banbury - Grimsbury & Hanwell Fields Mon-Sat Heyfordian 15 Oxford - Banbury via Middle Barton & C7: Mon-Sat C7/C8 Deddington* C8: Sun N S4 Stagecoach 16/17 C23 Route diversion to serve Kidlington Airport C23: Mon-Sat ‘County O n/a North Oxfordshire Dial-a-Ride Mon-Sat Centre Bus 18 Connect’ * Certain journeys only (see detailed service descriptions for clarification) Notes Parishes served: Where a parish is listed in [square brackets], the service passes through the parish but does not serve the main area of population. -

Oxfordshire. Banbury

DIRECTORY.] OXFORDSHIRE. BANBURY. 25 Warwick Road sub-Office.-.A. W. .Askew, sub-post Councillors. master.-Open from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. week days §William Denchfield tWilliam Lake only. Letters dispatched at 8.30 a.m. 12.20 & 2, 3, §Edward Humphrey Durran tWilliam Palmar 5.30, 6.30 & 7·45 p.m §Percy Spencer Edmunds tWilliam Lampet Whitehorn Pillar & Wall Letter Boxes Cleared §Alfred Benjamin :Field tH ubert Bartlett §William George 1\Ianwaring tJoseph John Chard Bridge Street piHar box, 5.15 & 8.30 a.m.; 12.20, 2, 3, §Henry Richard Webb tWilliam Robert Cooper 5·45, 6.30 .& 7· 45 p.m. ; sundays, 5.15 p.m. ; G. W. tWilliam James Bloxham !Lewis Wycherley Stone Railway Station wall box, 5· 15 & 8.30 a. m. ; 12:2o, t Arthur Fairfax tWilliam Tom Wakelin 2, 3, 5·45, 6.30 & 7·45 p.m. Grimsbury wall box, tJohn Hyde !John Wilks 5.15 & 8.30 a.m.; 12.20, 2, 3, 5·35, 6.30 & 7·45 p.m.; sundays, 5.15 p.m. Market Place pillar- box, 5.50 Marked thus § retire in 1895· Marked thus t retire in 1896. & 8.30 a.m.; 12.20, 2, 3, 5·45• 6.30 & 7·45 p.m. Broughton Terrace pillar box, s.xs & 8.30 a.m.; Marked thus + retire in 1897. 12.20, 2, 3, 6, 6.30 & 7·45 p.m. Neithrop wall box, Marked thus * retire in 1898. 5.15 & 8.30 a.m.; 12.20, 2, 5·45, 6.30 & 7·45 E'.ective Auditors, Henry Page & George Watson p.m.; sundays, 5.15 p.m. -

WARD SUMMARY Name of Ward Councillors Banbury 5 Three

WARD SUMMARY Name of Ward Councillors Electorate 2014 Electorate 2020 Variance 2020 Banbury 5 three member wards 15 35584 41262 6.6% Bicester East 3 7212 7774 0.4% Bicester North 3 6020 7167 -7.4% Bicester South 3 5591 7405 -4.3% Bicester West 3 7148 7432 -4.0% Kidlington North 3 6955 7420 -4.1% Kidlington South and Yarnton 3 8125 8363 8.0% Bloxham, Bodicote, Milton, Milcombe, 3 7302 8164 5.5% Wiggington, St Newington and Hook Norton Deddington and Adderbury 3 6972 7408 -4.3% Fringford and Heyfords 3 5893 7196 -7.0% Launton and Otmoor 3 6156 7158 -7.5% Wroxton 3 6686 7081 -8.5% Total 48 109,644 123,830 BLOXHAM, BODICOTE VILLAGE, MILTON, MILCOMBE, WIGGINGTON, SOUTH NEWINGTON AND HOOK NORTON WARD Polling Parish Existing Ward Electorate 2014 Electorate 2020 District CBM1 Bloxham Bloxham & Bodicote 2794 3290 CBN1 Bodicote (Village Ward) Bloxham & Bodicote 1772 1929 CCQ1 Milcombe Bloxham and Bodicote 496 514 CDO1 Wigginton Hook Norton 155 160 CDF1 South Newington Hook Norton 259 268 CCJ1 Hook Norton Hook Norton 1676 1846 CCR1 Milton Adderbury 150 157 Total 7302 8164 DEDDINGTON WARD Polling Parish Existing Ward Electorate 2014 Electorate 2020 District CAA1 Adderbury Adderbury 2235 2458 CAY1 Barford St John and St Deddington 462 464 Michael CBW1 Deddington Deddington 1304 1461 CBX1 Deddington Deddington 190 198 CBY1 Deddington Deddington 229 236 CCA1 Duns Tew The Astons and Heyfords 408 415 CCE1 Fritwell The Astons and Heyfords 536 541 CCO1 Middle Aston The Astons and Heyfords 105 114 CCV1 North Aston The Astons and Heyfords 158 160 CDD1 Somerton