Brian Pearce (1915-2008)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 3 No. 4, August–September 1958

Vol. 3 AUGUST"SEPTEMBER 1958 No.4 SOCIALISTS AND TRADE UNIONS Three Conferences 97 'Export of Revolution' 104 Freedom 011 the Individual 119 Labour's 1951 Defeat '25 . Science and Socialism 128 SUMMER BOOKS_____ -. reviewed by HENRY COLLINS, JOHN DANIELS, TOM KEMP, STANLEY EVANS, DOUGLAS GOLDRING, BRIAN PEARCE and others TWO SHILLINGS 266 Lavender Hill, London S.W. II Editors: John Daniels, Robert Shaw Business Manager: Edward R. Knight Contents EDITORIAL Three Conferences 97 SOt:IALISTS AND THE TRADE UNIONS Brian Behan 98 . 'EXPORT OF REVOLUTION', 19l7-1924 Brian Pearce lO4 FREEDOM OF THE INDIVIDUAL Peter Fryer 119 COMMUNICATIONS Stalinism and the Defeat of the 1945-51 Labour Governments Peter Cadogan 125 Science and Socialism G. N. Anderson 128 SUMMER BOOKS The New Ghana, by J. G. Amamoo Ekiomenesekenigha 109 The First International, ed. and trans. by Hans Gerth Henry Collins 110 Germany and the Revolution in Russia, 1915-1918, ed. by Z. A. B. Zeman B.P. 110 Stalin's C(}rresp~ndence with Churchill, At-tlee, Roosevelt and Truman, 1941-45 Brian Pearce 111 The Economics of Communist Eastern Europe, by Nicolas Spulber Tom Kemp III The Epic Strain in the English Novel, by E. M. W. Tillyard S.F.H. 113 A Victorian Eminence, by Giles St Aubyn K. R. Andrews 114 The Sweet and Twenties, by Beverley Nichols Douglas Goldring 114 Soviet Education for Science and Technoiogy, by A. G. Korol John Daniels ll5 Seven Years Solitary, by Edith Bone J.C.D. 115 The Kingdom of Free Men, by G. Kitson Clark Stanley Evans 116 On Religion, by K. -

A Brief History of Rank and File Movements

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk McIlroy, John (2016) A brief history of rank and file movements. Critique: Journal of Socialist Theory, 44 (1-2) . pp. 31-65. ISSN 0301-7605 [Article] (doi:10.1080/03017605.2016.1173823) Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/20157/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

The Communist Movement

$27.00 the set £11.90 the set The Communist Movement: From Comintern to Cominform by Fernando Claudín Translated by Brian Pearce Part One: The Crisis of the Communist International Part Two: The Zenith of Stalinism Modern history, the history of Europe and much of the rest of the world since World War 1, cannot be understood apart from the role of the Communist movement. And the world Communist movement is known almost exclusively from the woefully inaccurate ac- counts and interpretations of orthodox, anti- Communist scholars on the one side and Communist scholars on the other. In these contrasting interpretations, the element of agreement often outweighs the points of con- flict: this element of agreement is a mythology that describes world Communism, through- out its existence, as a dedicated insurgent phenomenon, “revolutionary” in its own eyes, “subversive” in those of its opponents. Fernando Claudín’s exhaustive and mas- terful history, the first adequate study from the Marxist viewpoint, will finally destroy all such tottering mythologies. The author here combines, in this massive work, the disci- plines of historical scholarship with the revo- lutionary standpoint from which alone it is possible to develop a critique of the theory and practice of the world Communist move- ment. His meticulous documentation offers to the reader a guarantee of historical accu- racy, while the revolutionary convictions with which the work is suffused bring to life the issues and battles it interprets and relives. The first volume opens with the dissolution -

Congress of the Peoples of the East BAKU, SEPTEMBER 1920

Congress of the Peoples of the East BAKU, SEPTEMBER 1920 STENOGRAPHIC REPORT Translated and annotated by Brian Pearce NEW PARK PUBLICATIONS Published by New Park Publications Ltd., 21b Old Town, Clapham, London SW4 OJT First English edition First published in Russian by the Publishing House of the Communist International, Petrograd, 1920 Translation, notes and foreword Copyright ©New Park Publications Ltd. 1977 Set up, Printed and Bound by Trade Union Labour Distributed in the United States by: Labor Publications Inc., 540 West 29th Street, New York New York 10011 ISBN 0 902030 90 6 Printed in Great Britain by Astmoor Litho Ltd. (TU), 21-22 Arkwright Road, Astmoor, Runcorn, Cheshire Contents Foreword IX Bibliographical Note XV Summons to the Congress 1 Ceremonial joint meeting 7 First Session, September 1 21 Second Session, September 2 38 Third Session, September 4 59 Fourth Session, September 4 69 Fifth Session, September 5 89 Sixth Session, September 6 120 Seventh Session, September 7 145 Manifesto of the Congress 163 Appeal to the workers of Europe 174 Appendices I Appeal from the Netherlands 183 II Composition of the Congress 187 Explanatory Notes 189 Index 201 Foreword The Congress of the Peoples of the East held in Baku in September, 1920 holds a special place in the history of the Communist movement. It was the first attempt to appeal to the exploited and oppressed peoples in the colonial and semi-colonial countries to carry forward their revolutionary struggles under the banner of Marxism and with the support of the workers in Russia and the advanced countries of the world. -

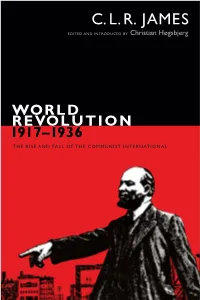

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED and INTRODUCED by Christian Høgsbjerg

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED AND INTRODUCED BY Christian Høgsbjerg WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 THE RISE AND FALL OF THE COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 ||||| C. L. R. James in Trafalgar Square (1935). Courtesy of Getty Images. the c. l. r. james archives recovers and reproduces for a con temporary audience the works of one of the great intel- lectual figures of the twentiethc entury, in all their rich texture, and will pres ent, over and above historical works, new and current scholarly explorations of James’s oeuvre. Robert A. Hill, Series Editor WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 The Rise and Fall of the Communist International ||||| C. L. R. J A M E S Edited and Introduced by Christian Høgsbjerg duke university press Durham and London 2017 Introduction and Editor’s Note © 2017 Duke University Press World Revolution, 1917–1936 © 1937 C. L. R. James Estate Harry N. Howard, “World Revolution,” Annals of the American Acad emy of Po liti cal and Social Science, pp. xii, 429 © 1937 Pioneer Publishers E. H. Carr, “World Revolution,” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1931–1939) 16, no. 5 (September 1937), 819–20 © 1937 Wiley All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Arno Pro and Gill Sans Std by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: James, C. L. R. (Cyril Lionel Robert), 1901–1989, author. | Høgsbjerg, Christian, editor. Title: World revolution, 1917–1936 : the rise and fall of the Communist International / C. L. R. James ; edited and with an introduction by Christian Høgsbjerg. -

Download Download

The International Newsletter of Communist Studies XXIV/XXV (2018/19), nos. 31-32 53 SECTION IV. STUDIES AND MATERIALS Pierre Broué † Institut d'études politiques de Grenoble France (translated by Brian Pearce †) The International Oppositions in the Communist International. A Global Overview Editors’ introduction This unpublished text by Pierre Broué (1926–2005), eminent French historian of international communism and Leo Trotsky, and avid contributor to the International Newsletter, was written under the title “The International Oppositions in the Comintern” in the 1990s for a planned, yet not implemented publication project of the International Institute of Social History (IISG) in Amsterdam. It was translated into English by British historian Brian Pearce (1915–2008). The typescript survived in Bernhard H. Bayerlein’s private collection, and as this text is not available anywhere in English, we decided to publish it here for the first time. Broué’s contribution is much more than the modest title suggests. His essay is not just a history of the oppositions within the Comintern, but a global overview and synthesis of oppositional currents in international communism in the 1920s, from the US to Indochina, from Switzerland to South Africa. Even though it has been written before the opening of several archives which are accessible today, such a global overview, combined with Broué’s poignant analysis, still can greatly benefit today’s researchers. We have left the text and the footnotes intact, merely adjusting the references to the International Newsletter’s citation style, correcting minor typos, and adding page numbers to the references to contributions in Cahiers Léon Trotsky, the scholarly journal edited by Pierre Broué. -

Left Pamphlet Collection

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: Special Collection Title: Left Pamphlet Collection Scope: A collection of printed pamphlets relating to left-wing politics mainly in the 20th century Dates: 1900- Extent: over 1000 items Name of creator: University of Sheffield Library Administrative / biographical history: The collection consists of pamphlets relating to left-wing political, social and economic issues, mainly of the twentieth century. A great deal of such material exists from many sources but, as such publications are necessarily ephemeral in nature, and often produced in order to address a particular issue of the moment without any thought of their potential historical value (many are undated), they are frequently scarce, and holding them in the form of a special collection is a means of ensuring their preservation. The collection is ad hoc, and is not intended to be comprehensive. At the end of the twentieth century, which was a period of unprecedented conflict and political and economic change around the globe, it can be seen that (as with Fascism) while the more extreme totalitarian Socialist theories based on Marxist ideology have largely failed in practice, despite for many decades posing a revolutionary threat to Western liberal democracy, many of the reforms advocated by democratic Socialism have been to a degree achieved. For many decades this outcome was by no means assured, and the process by which it came about is a matter of historical significance which ephemeral publications can help to illustrate. The collection includes material issued from many different sources, both collective and individual, of widely divergent viewpoints and covering an extensive variety of topics. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Adler, Alan (ed.) 1980, Theses, Resolu- Councils, 1905–1921, translated by Ruth tions, and Manifestos of the First Four Hein, New York: Random House. Congresses of the Third International, Armstrong, John Alexander 1961, The Poli- translated by Alix Holt and Barbara tics of Totalitarianism: The Communist Holland, London: Ink Links. Party of the Soviet Union from 1934 to Albrow, Martin 1970, Bureaucracy, New the Present, New York: Random House. York: Praeger Publishers. Arthur, C.A. 1972, ‘The Coming Soviet Rev- Aleksandrov, A. 1899, Polnyi anglo-russkii olution’, in Trotsky: The Great Debate slovar’, St. Petersburg: V Knizhnom i Renewed, edited by Nicolas Krasso, Geograficheskom Magazinie izdanii 151–91, St. Louis, MO: New Critics Press. Glavnago Shtaba. Aulard, Alphonse 1910, The French Revo- ―― 1909, Polnyi anglo-russkii slovar’, lution: A Political History, 1789–1804, Berlin: Polyglotte. in four volumes, vol. 4, The Bourgeois Alexander, Robert Jackson 1991, Interna- Republic and the Consulate, New York: tional Trotskyism, 1929–1985: A Docu- Charles Scribner’s Sons. mented Analysis of the Movement, Avineri, Shlomo 1968, The Social and Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. Political Thought of Karl Marx, Cam- Anderson, Kevin 1995, Lenin, Hegel, and bridge: Cambridge University Press. Western Marxism: A Critical Study. ―― 1972, ‘The Hegelian Origins of Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. Marx’s Political Thought’, in Marx’s Anderson, Perry 1984, ‘Trotsky’s Inter- Socialism, edited by Shlomo Avineri, pretation of Stalinism’, in The Stalinist New York: Lieber-Atherton. Legacy: its Impact on Twentieth- Avrich, Paul 1970, Kronstadt 1921, New Century World Politics, edited by Tariq York: W.W. -

Communists Text

The University of Manchester Research Communists and British Society 1920-1991 Document Version Proof Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K., Cohen, G., & Flinn, A. (2007). Communists and British Society 1920-1991. Rivers Oram Press. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:30. Sep. 2021 INTRODUCTION A dominant view of the communist party as an institution is that it provided a closed, well-ordered and intrusive political environment. The leading French scholars Claude Pennetier and Bernard Pudal discern in it a resemblance to Erving Goffman’s concept of a ‘total institution’. Brigitte Studer, another international authority, follows Sigmund Neumann in referring to it as ‘a party of absolute integration’; tran- scending national distinctions, at least in the Comintern period (1919–43) it is supposed to have comprised ‘a unitary system—which acted in an integrative fashion world-wide’.1 For those working within the so-called ‘totalitarian’ paradigm, the validity of such ‘total’ or ‘absolute’ concep- tions of communist politics has always been axiomatic. -

Bio-Bibliographical Sketch of John G. Wright

Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet John G. Wright Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: Basic biographical data Biographical sketch Selective bibliography Sidelines, notes on archives Basic biographical data Name: John G. Wright Other names (by-names, pseud. etc.): The mad Russian * Usick * Joseph Vanzler * Usick Vanzler * J.G.W. * J.G. Wright Date and place of birth: Nov. 29, 1901, Samarkand (Russian Empire) Date and place of death: June 21, 1956, New York, NY (USA) Nationality: Russian, USA Occupations, careers, etc.: Chemist, multi-lingual translator, journalist, editor Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1933 - 1956 Biographical sketch John G. Wright was an outstanding intellectual leader of the American Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and be- came particularly known as a translator of many works of Leon Trotsky into English. The following biographical sketch is chiefly based upon obituaries and other biographical items mentioned in the next-to-the last paragraph of the Selective bibliography below. Joseph Vanzler, better known under either his pen name John G. Wright or by his nickname Usick, was born in 1901 [according to N.Y. naturalization record] in Samarkand (Uzbekistan, Central Asia, then a part of the Czarist Russian Empire) as son of an old rabbi and a girl of only 14 years of age. As one of only a handful Jewish children1 in his home-town, the young Vanzler was permitted to attend a Russian school where the aspiring pupil among other things excellently learned vernacular and Court Russian, Latin, Greek and French. After the outbreak of World War I, his mother together with Joseph emigrated to the United States and settled in Boston, Mass., where she married Max Cohen who later got a rich man as owner of a company. -

The German Revolution, 1917-1923 (Historical Materialism Book Series

THE GERMAN REVOLUTION, 1917-1923 HISTORICAL MATERIALISM BOOK SERIES Editorial board PAUL BLACKLEDGE, Leeds - SEBASTIAN BUDGEN, Paris JIM KINCAID, Leeds - STATHIS KOUVELAKIS, Paris MARCEL VAN DER LINDEN, Amsterdam CHINA MIÉVILLE, London - PAUL REYNOLDS, Lancashire THE GERMAN REVOLUTION 1917-1923 By Pierre Broue´ Translated by John Archer and Edited by Ian Birchall and Brian Pearce With an Introduction by Eric D. Weitz BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Original title: La révolution en Allemagne, 1917-1923 © Pierre Broué, Les Editions de Minuit, 1971 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Broué, Pierre. [Révolution en Allemagne, 1917-1923. English] The German Revolution / by Pierre Broué ; [translated by John Archer and edited by Ian Birchall and Brian Pearce]. p. cm. — (Historical materialism book series, ISSN 1570-1522 ; 5) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-13940-0 (alk. paper) 1. Germany—Politics and government—1918-1933. 2. World War, 1914-1918—Germany. 3. Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands—History. 4. Germany—History—Revolution, 1918. I. Title. II. Series. DD240.B81613 2004 943.085—dc22 2004040884 ISSN 1570–1522 ISBN 90 04 13940 0 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

A Trotsky Digest

unevenandcombined.com: Trotsky Digest U&CD: a Trotsky Digest With the exception of the opening chapter of The History of the Russian Revolution, Trotsky nowhere provides a concentrated exposition of the idea of uneven and combined development. Instead, materials relevant to the idea are found scattered widely across his works – a paragraph here, a sentence there, sometimes just a suggestive phrase almost hidden by a surrounding mass of irrelevant polemics. This document assembles a variety of such materials which I have found useful for thinking about the idea. The materials are arranged by source (rather than thematically). And the sources themselves are arranged chronologically, with dates in parentheses to indicate when the texts were written. Words in square brackets are not Trotsky’s. This document is not a substitute for reading the originals, but it may help direct you to passages of special relevance. Note that the critical remarks by James Burnham on pages 20-21, though republished in a volume of Trotsky’s writings, are of course by Burnham himself. If you have any suggestions for additional passages to include, please email them to me, with the full references, at [email protected] 1 unevenandcombined.com: Trotsky Digest Contents 1 Results and Prospects (1906) in The Permanent Revolution and Results and Prospects, translated by Brian Pearce, London, New Park Publications: 1962. 3 2 1905, (1908-9/1922) translated by Anya Bostock, Harmondsworth, Penguin: 1973. 6 3 Leon Trotsky on Britain, (1925-28) introduced by George Novack, New York, Monad Press: 1973. 8 4 The Third International After Lenin (1929) translated by John G.