The Communist Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spanish Communist Party in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), Vol

The Defence of Madrid: The Spanish Communist Party in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), Vol. Amanda Marie Spencer Ph. D. History Department of History, University of Sheffield June 2006 i Contents: - List of plates iii List of maps iv Summary v Introduction 5 1 The PCE during the Second Spanish Republic 17 2 In defence of the Republic 70 3 The defence of Madrid: The emergence of communist hegemony? 127 4 Hegemony vs. pluralism: The PCE as state-builder 179 5 Hegemony challenged 229 6 Hegemony unravelled. The demise of the PCE 274 Conclusion 311 Appendix 319 Bibliography 322 11 Plates Between pp. 178 and 179 I PCE poster on military instruction in the rearguard (anon) 2a PCE poster 'Unanimous obedience is triumph' (Pedraza Blanco) b PCE poster'Mando Unico' (Pedraza Blanco) 3 UGT poster'To defend Madrid is to defend Cataluna' (Marti Bas) 4 Political Commissariat poster'For the independence of Spain' (Renau) 5 Madrid Defence Council poster'First we must win the war' (anon) 6a Political Commissariat poster Training Academy' (Canete) b Political Commissariat poster'Care of Arms' (anon) 7 lzquierda Republicana poster 'Mando Unico' (Beltran) 8 Madrid Defence Council poster'Popular Army' (Melendreras) 9 JSU enlistment poster (anon) 10 UGT/PSUC poster'What have you done for victory?' (anon) 11 Russian civil war poster'Have you enlisted as a volunteer?' (D.Moor) 12 Poster'Sailors of Kronstadt' (Renau) 13 Poster 'Political Commissar' (Renau) 14a PCE Popular Front poster (Cantos) b PCE Popular Front poster (Bardasano) iii Maps 1 Central Madrid in 1931 2 Districts of Madrid in 1931 2 3 Province of Madrid 3 4 District of Cuatro Caminos 4 iv Summary The role played by the Spanish Communist Party (Partido Comunista de Espana, PCE) during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39 remains controversial to this day. -

Overview of Organizational Developments in Spanish Anti-Revisionism

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line * Spain Overview of Page | 1 organisational developments First Published: May 2019 Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. In 1963 the first anti-revisionists Marxist-Leninist organisations arose, and after that, various others developed either through subsequent splits or by indirect or direct routes, not least the student movement and catholic circles influenced by Marxism. Like elsewhere in Europe, inspired by the Sino-Soviet Polemic and later the Cultural Revolution, there was an organisational rupture, a separation from the revisionist party, but how much of a political, ideological and organisational rupture was there? The proliferation of small militants groups1, and an inability to rally a stable recognised leadership that could command allegiance amongst the various trends saw unresolved ideological concerns engendered criticism and splits that were never resolved in any organisation that could act as, rather than proclaim itself, the successor of the PCE. Spanish anti-revisionists operated under a repressive authoritarian regime headed by Franco whose military coup had overthrown the Spanish republic. It was a heroic struggle in a regime noted for its anti-communist repression and police killing demonstrating workers in the streets, generating an armed response of differing intensity and effectiveness. -

Some Questions Concerning the Crisis of Marxist Theory and of the International Communist Movement

Historical Materialism �3.� (�0�5) �5�–�78 brill.com/hima Some Questions Concerning the Crisis of Marxist Theory and of the International Communist Movement Louis Althusser I feel very honoured and moved to be able to speak before you all today, thanks to the kind invitation of the Catalan College of Building Engineers and Technical Architects. This is the third time that I have spoken in Spain. The first time was in Granada, during Easter 1976. I gave a talk on whether or not we can speak of the existence of a Marxist philosophy. The second time was a few days later in Madrid, where I gave the same talk. Several thousand students came to each. In Granada there were too many people for a public debate, but in Madrid a discussion was possible thanks to the disposition of the venue’s management, and even despite the great number of students. They asked me questions on the French and Spanish political situation and the abandonment of the dictatorship of the proletariat by the Twenty-Second Congress of the French Communist Party (PCF). I answered all of their questions, but I got the impres- sion that much of the audience thought that my talk was too much philosophy and not enough politics. I know that I am today speaking in a city where the popular and democratic forces have reconquered the right to wage their struggle out in the open, and that if today I can speak before you freely – and speak freely about politics – then I owe this to the struggle waged by the popular forces of Barcelona. -

Vol. 3 No. 4, August–September 1958

Vol. 3 AUGUST"SEPTEMBER 1958 No.4 SOCIALISTS AND TRADE UNIONS Three Conferences 97 'Export of Revolution' 104 Freedom 011 the Individual 119 Labour's 1951 Defeat '25 . Science and Socialism 128 SUMMER BOOKS_____ -. reviewed by HENRY COLLINS, JOHN DANIELS, TOM KEMP, STANLEY EVANS, DOUGLAS GOLDRING, BRIAN PEARCE and others TWO SHILLINGS 266 Lavender Hill, London S.W. II Editors: John Daniels, Robert Shaw Business Manager: Edward R. Knight Contents EDITORIAL Three Conferences 97 SOt:IALISTS AND THE TRADE UNIONS Brian Behan 98 . 'EXPORT OF REVOLUTION', 19l7-1924 Brian Pearce lO4 FREEDOM OF THE INDIVIDUAL Peter Fryer 119 COMMUNICATIONS Stalinism and the Defeat of the 1945-51 Labour Governments Peter Cadogan 125 Science and Socialism G. N. Anderson 128 SUMMER BOOKS The New Ghana, by J. G. Amamoo Ekiomenesekenigha 109 The First International, ed. and trans. by Hans Gerth Henry Collins 110 Germany and the Revolution in Russia, 1915-1918, ed. by Z. A. B. Zeman B.P. 110 Stalin's C(}rresp~ndence with Churchill, At-tlee, Roosevelt and Truman, 1941-45 Brian Pearce 111 The Economics of Communist Eastern Europe, by Nicolas Spulber Tom Kemp III The Epic Strain in the English Novel, by E. M. W. Tillyard S.F.H. 113 A Victorian Eminence, by Giles St Aubyn K. R. Andrews 114 The Sweet and Twenties, by Beverley Nichols Douglas Goldring 114 Soviet Education for Science and Technoiogy, by A. G. Korol John Daniels ll5 Seven Years Solitary, by Edith Bone J.C.D. 115 The Kingdom of Free Men, by G. Kitson Clark Stanley Evans 116 On Religion, by K. -

A Brief History of Rank and File Movements

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk McIlroy, John (2016) A brief history of rank and file movements. Critique: Journal of Socialist Theory, 44 (1-2) . pp. 31-65. ISSN 0301-7605 [Article] (doi:10.1080/03017605.2016.1173823) Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/20157/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Communist Trade Unionism and Industrial Relations on the French Railways, 1914–1939

Fellow Travellers Communist Trade Unionism and Industrial Relations on the French Railways, 1914–1939 STUDIES IN LABOUR HISTORY 13 Studies in Labour History ‘…a series which will undoubtedly become an important force in re-invigorating the study of Labour History.’ English Historical Review Studies in Labour History provides reassessments of broad themes along with more detailed studies arising from the latest research in the field of labour and working-class history, both in Britain and throughout the world. Most books are single-authored but there are also volumes of essays focussed on key themes and issues, usually emerging from major conferences organized by the British Society for the Study of Labour History. The series includes studies of labour organizations, including international ones, where there is a need for new research or modern reassessment. It is also its objective to extend the breadth of labour history’s gaze beyond conven- tionally organized workers, sometimes to workplace experiences in general, sometimes to industrial relations, but also to working-class lives beyond the immediate realm of work in households and communities. Fellow Travellers Communist Trade Unionism and Industrial Relations on the French Railways, 1914–1939 Thomas Beaumont Fellow Travellers LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2019 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2019 Thomas Beaumont The right of Thomas Beaumont to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Popular Front, War and Internationalism in Catalonia During the Spanish Civil War Josep Puigsech Farràs Universitat Autònoma De Barcelona, [email protected]

Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies Journal of the Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies Volume 37 | Issue 1 Article 8 2012 Popular Front, war and internationalism in Catalonia during the Spanish Civil War Josep Puigsech Farràs Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.asphs.net/bsphs Recommended Citation Puigsech Farràs, Josep (2012) "Popular Front, war and internationalism in Catalonia during the Spanish Civil War," Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies: Vol. 37 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. https://doi.org/10.26431/0739-182X.1079 Available at: https://digitalcommons.asphs.net/bsphs/vol37/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies by an authorized editor of Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Popular Front, war and internationalism in Catalonia during the Spanish Civil War Cover Page Footnote This article was made possible thanks to the project funded by the Ministry of Education and Culture of Spain, The cultures of fascism and anti-fascism in Europe (1894-1953), HAR2008-02582/HIST code. This article is available in Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies: https://digitalcommons.asphs.net/bsphs/vol37/ iss1/8 BULLETIN FOR SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE HISTORICAL STUDIES 37:1/December 2012/146-165 Popular Front, war and internationalism in Catalonia during the Spanish Civil War* JOSEP PUIGSECH FARRÀS Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Catalan Nationalist discourse was not exclusive to progressive liberalism from the early twentieth century, it was also present in Marxism. -

'Against the State': a Genealogy of the Barcelona May Days (1937)

Articles 29/4 2/9/99 10:15 am Page 485 Helen Graham ‘Against the State’: A Genealogy of the Barcelona May Days (1937) The state is not something which can be destroyed by a revolution, but is a condition, a certain relationship between human beings, a mode of human behaviour; we destroy it by contracting other relationships, by behaving differently.1 For a European audience, one of the most famous images fixing the memory of the Spanish Civil War is of the street fighting- across-the-barricades which occurred in Barcelona between 3 and 7 May 1937. Those days of social protest and rebellion have been represented in many accounts, of which the single best known is still George Orwell’s contemporary diary account, Homage to Catalonia, recently given cinematic form in Ken Loach’s Land and Freedom. It is paradoxical, then, that the May events remain among the least understood in the history of the civil war. The analysis which follows is an attempt to unravel their complexity. On the afternoon of Monday 3 May 1937 a detachment of police attempted to seize control of Barcelona’s central telephone exchange (Telefónica) in order to remove the anarchist militia forces present therein. News of the attempted seizure spread rapidly through the popular neighbourhoods of the old town centre and port. By evening the city was on a war footing, although no organization — inside or outside government — had issued any such command. The next day barricades went up in central Barcelona; there was a generalized work stoppage and armed resistance to the Catalan government’s attempt to occupy the telephone exchange. -

Congress of the Peoples of the East BAKU, SEPTEMBER 1920

Congress of the Peoples of the East BAKU, SEPTEMBER 1920 STENOGRAPHIC REPORT Translated and annotated by Brian Pearce NEW PARK PUBLICATIONS Published by New Park Publications Ltd., 21b Old Town, Clapham, London SW4 OJT First English edition First published in Russian by the Publishing House of the Communist International, Petrograd, 1920 Translation, notes and foreword Copyright ©New Park Publications Ltd. 1977 Set up, Printed and Bound by Trade Union Labour Distributed in the United States by: Labor Publications Inc., 540 West 29th Street, New York New York 10011 ISBN 0 902030 90 6 Printed in Great Britain by Astmoor Litho Ltd. (TU), 21-22 Arkwright Road, Astmoor, Runcorn, Cheshire Contents Foreword IX Bibliographical Note XV Summons to the Congress 1 Ceremonial joint meeting 7 First Session, September 1 21 Second Session, September 2 38 Third Session, September 4 59 Fourth Session, September 4 69 Fifth Session, September 5 89 Sixth Session, September 6 120 Seventh Session, September 7 145 Manifesto of the Congress 163 Appeal to the workers of Europe 174 Appendices I Appeal from the Netherlands 183 II Composition of the Congress 187 Explanatory Notes 189 Index 201 Foreword The Congress of the Peoples of the East held in Baku in September, 1920 holds a special place in the history of the Communist movement. It was the first attempt to appeal to the exploited and oppressed peoples in the colonial and semi-colonial countries to carry forward their revolutionary struggles under the banner of Marxism and with the support of the workers in Russia and the advanced countries of the world. -

Strategy and Structure in the 2010-11 University of Puerto Rico Student Strike

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2016 Struggling to Learn, Learning to Struggle: Strategy and Structure in the 2010-11 University of Puerto Rico Student Strike José A. Laguarta Ramírez Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1359 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] STRUGGLING TO LEARN, LEARNING TO STRUGGLE: STRATEGY AND STRUCTURE IN THE 2010-11 UNIVERSITY OF PUERTO RICO STUDENT STRIKE by JOSÉ A. LAGUARTA RAMÍREZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New Yoek. 2016 © 2016 JOSÉ A. LAGUARTA RAMÍREZ All Rights Reserved ii Struggling to Learn, Learning to Struggle: Strategy and Structure in the 2010-11 University of Puerto Rico Student Strike by José A. Laguarta Ramírez This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Susan L. Woodward Chair of Examining Committee Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Susan L. Woodward Vincent Boudreau Frances Fox Piven THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Struggling to Learn, Learning to Struggle: Strategy and Structure in the 2010-11 University of Puerto Rico Student Strike by José A. -

Hurrah Revolutionaries and Polish Patriots: the Polish Communist Movement in Canada, 1918-1950

Hurrah Revolutionaries and Polish Patriots: The Polish Communist Movement in Canada, 1918-1950 Patryk Polec Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Post Doctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Patryk Polec, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 ABSTRACT This thesis constitutes the first full-length study of Polish Communists in Canada, a group that provided a substantial segment of the countries socialist left in the early 20th century. It traces the roots of socialist support in Poland, its transplantation to Canada, the challenges it faced within an ethnic community heavily influenced by Catholicism, the complications caused by its links to the Comintern, and its changing strength and decline. It offers a deeper understanding of the ways in which the Communist party was able to appeal to certain ethnic groups, such as through cultural outreach, as well as its complicated and often arguably counter- productive relationship with the Comintern. It also furnishes important information on the efforts of the RCMP and Polish consulates to maintain control over the communists, as well as how generally improved material conditions among Poles, especially following the Second World War, along with the influence of the Cold War, accounted for a rapid decline in support. The thesis is primarily based on sources generated by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs or, more precisely, by the Polish consulates in Winnipeg, Montreal and Ottawa. One the Canadian side, the thesis took advantage of RCMP records, Canadian security bulletins, immigration records and Polish-language newspapers printed in Canada. -

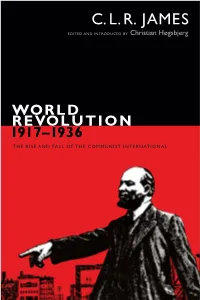

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED and INTRODUCED by Christian Høgsbjerg

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED AND INTRODUCED BY Christian Høgsbjerg WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 THE RISE AND FALL OF THE COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 ||||| C. L. R. James in Trafalgar Square (1935). Courtesy of Getty Images. the c. l. r. james archives recovers and reproduces for a con temporary audience the works of one of the great intel- lectual figures of the twentiethc entury, in all their rich texture, and will pres ent, over and above historical works, new and current scholarly explorations of James’s oeuvre. Robert A. Hill, Series Editor WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 The Rise and Fall of the Communist International ||||| C. L. R. J A M E S Edited and Introduced by Christian Høgsbjerg duke university press Durham and London 2017 Introduction and Editor’s Note © 2017 Duke University Press World Revolution, 1917–1936 © 1937 C. L. R. James Estate Harry N. Howard, “World Revolution,” Annals of the American Acad emy of Po liti cal and Social Science, pp. xii, 429 © 1937 Pioneer Publishers E. H. Carr, “World Revolution,” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1931–1939) 16, no. 5 (September 1937), 819–20 © 1937 Wiley All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Arno Pro and Gill Sans Std by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: James, C. L. R. (Cyril Lionel Robert), 1901–1989, author. | Høgsbjerg, Christian, editor. Title: World revolution, 1917–1936 : the rise and fall of the Communist International / C. L. R. James ; edited and with an introduction by Christian Høgsbjerg.