“The State of Jefferson”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dining with Anna and Friends

Dining with Anna and Friends This list of restaurants, bars, delis, and food stores are related in one way or another to The Tales of the City (books and/or films) as well as to The Night Listener. They are grouped by neighborhoods or areas in San Francisco. Some have already been included in existing walking tours. More will be included in future tours. Many establishments – particularly bars and clubs – featured in Armistead Maupin’s books have since closed. The buildings were either vacant or have been converted into other types of businesses altogether (for example, one has been turned into a service for individuals who are homeless) at the time this list was created. For these reasons, those establishments have not been included in this list. As with the rest of the content of the Tours of the Tales website, this list will be periodically updated. If you have updates, please forward them to me. I appreciate your help. NOTE: Please do not consider this list an exhaustive list of eating/drinking establishments in San Francisco. For example, although there are several restaurants listed in “North Beach” below, there are many more excellent places in North Beach in addition to those listed. Also, do not consider this list an endorsement of any place included in the list. The Google map for this list of eating establishments: Dining with Anna and Friends. Aquatic Park/Fisherman’s Wharf/and the Embarcadero The Buena Vista Bar, 2765 Hyde Street (southwest corner of Hyde and Beach; across the street from the Powell-Hyde cable car turntable): Mary Ann Singleton was twenty-five years old when she saw San Francisco for the first time. -

Irish Dance and Lore of Folk & Square Dancing • March 1955

m& THE MAGAZINE OF FOLK & SQUARE DA• ANCINN G I J IMARCH • \955 • 25c IRISH DANCE AND LORE OF FOLK & SQUARE DANCING • MARCH 1955 Vol. 12 Official Publication of The Folk Dance Federation of PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS Calif., Inc. PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Calendar of Events 10 San Francisco Festival 3 President's Message Program CHARLES E. ALEXANDER 3 Host Cities 12 Tell It to Danny 4 Irish Dance and Song 12 Fresnotes 6 The Lepruchans I 3 Siamsa Beirte ANNE ALEXANDER 6 Why Folk Dance of Ireland 14 Beginners' Party are Different—and Difficult 15 The Record Finder AM? The Mr. and Mrs. of Irish 16 In Other States HILDA SACHS Dancing 16 Let's Dance Squares 17 The Promenade The Tara Brooch I 8 Report from Southern REN BACULO Recipes of the Month California Statewide Festival 19 Sacramento Area They'll Do It Every Time I 9 Puget Soundings PEG ALLMOND HENRY L. BLOOM ROBERT H. CHEVALIER PHIL EN6 ED FERRARiO LEE KENNEDY MIRIAM LiDSTER DANNY MCDONALD ELMA McFARLAND PAUL PRITCHARD CARMEN SCHWEERS MARY SPRING DOROTHY TAMBURIN1 President, North-Wm. F. Sorensen, 94 Cas- tro St., San Francisco, UNderhill 1-5402. Recording Secretary, North— Bea Whittier, LEE KENNEDY, 146 Dolores Street, San Francisco 3435 T Street, Sacramento, Calif. President, South-Minne Anstine, 242T/2 ELMA McFARLAND, I 77'A N. Hil! Aye., Pasadena 4 Castillo, Santa Barbara, Calif. Recording Secretary, South— Dorothy Lauters, Toro Canyon road, Federation Festivals Hosts: Silverado Folk Dancers. Carpinteria, Calif. APRIL 23, SATURDAY N1SHT. Westwood Town Auditorium MARCH 12, SATURDAY 8 p.m.-12 .midnight. -

The Fast and the Spurious

Delicious San Francisco More online Travel to Sonoma, plus The Tablehopper: It's time for Evalyn Barron, Coastal Salt & Straw, p. 10 Commuter, and more. Neighborhood Gem: Bistro Aix, p. 11 marinatimes.com MARINATIMES.COM CELEBRATING OUR 33RD YEAR VOLUME 33 ISSUE 05 MAY 2017 Reynolds Rap Living in la-la land San Francisco keeps spending while pension disaster looms BY SUSAN DYER REYNOLDS ast month, the san francisco school board voted unanimously to offer Vincent Matthews a three-year contract paying $310,000 per year, L$60,000 more than the $250,000 he made at his previ- ous job as state administrator for the Inglewood school district in Southern California. That’s a nice chunk of change, but the deal is made even sweeter by the fact that San Francisco will also cover all healthcare premiums for Matthews and his family, contribute $100,000 over the Layout artist McLaren Stewart, Walt Disney, and Eyvind Earle at The Walt Disney Studios during production next three years to a retirement account, and make pay- ments into state pension funds totaling around $140,000. for Sleeping Beauty, c. 1959 PHOTO: COURTESY OF EYVIND EARLE PUBLISHING, LLC An article in the San Francisco Chronicle pointed out that these are the same provisions received by his predeces- The Art of Eyvind Earle at the Walt Disney Family Museum sor, Richard Carranza, and are “fairly standard” in school districts across the state. It almost feels like the Chronicle BY SHARON ANDERSON shaped Disney favorites Lady and the lific artist’s life. At the age of 11, his is trying to justify what to me are outrageous benefits for Tramp (1955) and Peter Pan (1953), father challenged him to either read a city and state with bleeding, broken pension systems rom may 18 through jan. -

Iconic San Francisco Coffee Drinks

Iconic San Francisco Coffee Drinks WORDS Austin Langlois PHOTOGRAPHS Christiann Koepke Nestled in Northern California, San Francisco is known worldwide for its strong coffee culture. Some of S.F.’s best-known coffee drinks earned a cult following as an alternative to alcohol during Prohibition, and continued to gain popularity through the 1950s. More recent examples emerged from the current, third wave of thoughtful coffee sourcing, roasting, and brewing practices. These coffee drinks depart from the unadulterated preparations of craft coffee and present creative, and often sweeter, ways of drinking coffee. 34 SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO 35 Snowy Plover Andytown’s famous iced-coffee soda, the Snowy Plover, is made for sunny days. Owners Lauren Crabbe and Michael McCrory have Affogato served it since opening day in 2014. Made with San Pellegrino sparkling water over ice (the ice keeps the fizz down when the espresso The Affogato Bar on the upper level of the Sightglass flagship bar and roaster on 7th Street transforms this traditional Italian treat. is added), brown sugar syrup, and a double shot of espresso, it’s topped off with a quenelle of house-made whipped cream and a pinch Typically in Italy, an affogato is constructed with a shot of espresso poured over a scoop of vanilla gelato, however Sightglass opts of Maldon sea salt. Proprietor Lauren Crabbe prefers to drink from the top down like she would a Guinness, but most prefer to stir it for Portland-based Salt & Straw ice cream, taking it a step further with ice cream flavors like honey lavender or sea salt with caramel all up with a straw. -

State of Jefferson

State of Jefferson By Jeff LaLande In all of American history, only two states have been formed from older states that were already admitted to the Union: Maine (from Massachusetts, in 1820) and West Virginia, during the Civil War. However, in 1941, some residents of northern-most California and southwestern Oregon—where people had long been resentful of the political power held in Sacramento and Salem by more populous districts—promoted the idea of a separate state. Believing that their largely rural region was not receiving its fair share of federal defense and state public-works money, their publicity-seeking "secession" movement gathered steam to form a forty-ninth state, the State of Jefferson. The protest echoed previous, short-lived efforts, similarly done largely to increase attention for the area among state legislators (for example, the State of Siskiyou proposed in 1909). The 1941 Jefferson “secession” effort was the brainchild of two well-known regional figures. Initiating the movement was entrepreneur and railroad speculator Gilbert Gable, the mayor of Port Orford. In the late 1930s, Gable had first promoted the concept of coastal Curry County becoming part of California as a way to increase infrastructure spending. Randolph Collier, the California state senator for Siskiyou County (he would later become known as the father of California's freeway system), joined the effort and helped make Yreka the capital of the State of Jefferson. As the federal government prepared for direct involvement in World War II, the so-called Jeffersonians used the stunt to call for the subsidized construction of roads into the remote mountains of their “state.” They launched the movement as a publicity gimmick to spur federal and state governments to spend the funds needed to tap natural resources such as strategic minerals and timber. -

The Livermore Roots Tracer Vol III No 3 Winter 1983

ROOTS TRACER \ Volume III WINTER 1983 No.3 Contents of th is Issue Page Editorial Notes 30 Odds & Ends 30 News from Other Organizations 31 Genealogical Aids Elderhostel 33 Valley Roots Cover Story - Arroyo Sanitorium 34 Meet the Members Edith Hunt Brittain 35 Elliott Hartman Dopking (1910-1983) 35 Society News 36 Searching Guide 36 How Adoptees Can Get Help 37 How To Set Up A Family Organization 38 Library News 40 Procedure For Encapsulation 40 Upcoming Events National Genealogical Conference in Son Francisco 41 Book Sale -- Plus 42 Word Processing - Beverly Ales. Publishing Courtesy of Bill Meier of Allied Brokers 1988 Fourth Street Livermore, CA 94550 Editorial Notes We would like to welcome the following new members: Linda K. Garrett, 1136 Hillcrest Court, Livermore, CA 94550 443-5170 Clyde Brewster, 758 Catalina Drive, Livermore, CA 94550 447-0748 We look forward to reading about your research in "Meet the Members" sometime this year. News from Alan Cranston regarding Senate Bill 905 (S.905), the proposed National Archives and Records Administration. You'll be happy to know that S.905 was approved for favorable reporting from the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee on November 17, 1983. He is a co-sponsor of this bill, and is convinced that the National Archives would be better managed and better able to fulfill its responsibilities if independent of GSA. Restoring the National Archives as a separate entity would, he believes, not only ensure the integrity of archival programs but encourage the Archives' cultural and educational functions. If you'd Iike to browse through the Sutro Library and see what's there without driving to San Francisco--be sure and ask Lucile White to show you the Sutro "new arrivals" list. -

The Pulitzer Prizes Winners An

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award...................................................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service................................................................................................................7 Reporting...................................................................................................................25 Local Reporting...........................................................................................................28 Local Reporting, Edition Time....................................................................................33 Local General or Spot News Reporting.......................................................................34 General News Reporting..............................................................................................37 Spot News Reporting...................................................................................................39 Breaking News Reporting............................................................................................40 Local Reporting, No Edition Time...............................................................................46 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting.................................................................48 Investigative Reporting................................................................................................51 Explanatory Journalism...............................................................................................61 -

FINAL EDITION Twilight of the American Newspaper by Richard Rodriguez the INTELLIGENCE FACTORY How America Makes Its Enemies

November CAN Subs cover Final2rev 9/29/09 8:19 AM Page 1 ANDREW J. BACEVICH: THE UNWINNABLE AFGHAN WAR HARPER’S MAGAZINE / NOVEMBER 2009 $7.95 ◆ FINAL EDITION Twilight of the American Newspaper By Richard Rodriguez THE INTELLIGENCE FACTORY How America Makes Its Enemies Disappear By Petra Bartosiewicz PROSPEROUS FRIENDS A story by Christine Schutt Also: Frederick Seidel and Mark Kingwell ◆ ESSAY FINAL EDITION Twilight of the American newspaper By Richard Rodriguez scholar I know, a woman who is ninety- postwar California suburbs. Herb Caen, whose six years old, grew up in a tin shack on column I read immediately—second section, Athe American prairie, near the Cana- corner left—invited me into the provincial cos- dian border. She learned to read from the pages mopolitanism that characterized the city’s out- of the Chicago Tribune in a one-room school- ward regard: “Isn’t it nice that people who prefer house. Her teacher, who had no more than an Los Angeles to San Francisco live there?” eighth-grade education, had once been to Chi- cago—had been to the opera! Women in Chi- ewspapers have become deadweight cago went to the opera with bare shoulders and commodities linked to other media long gloves, the teacher imparted to her pupils. Ncommodities in chains that are coupled Because the teacher had once been to Chicago, or uncoupled by accountants and lawyers and ex- she subscribed to the Sunday edition of the ecutive vice presidents and boards of directors in Chicago Tribune, which came on the train by offi ces thousands of miles from where the man Tuesday, Wednesday at the latest. -

Link to Magazine Issue

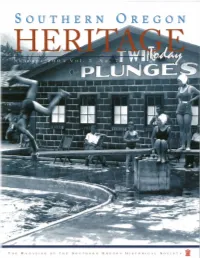

"'iiii" .... AJ_ 3 1 :J0 S ,V:J I BO .LSI H NOCl3BO N B31-1lnOS 31-1 .L ::1O 3 ,\JIZVClVW 31-11- ~a~ IISOUTHERNI OREGON HISTORICAL S OCIETY fr~m tll~ mr~~t~r Board of Trus tees Neil Thorson. M~dfonif PRESlDEl\'T DEAR SOHS MEMBER: Judi Drais, Mnifcrrri, FlRST VICE-PRESIDENT H ank Hart, Mnlforri, SECQ:-..tO VICE-PRESIDENT -Ii Robert Stevens, jadw')11vil/r, SECRETARY On Friday, May 30, the Society held Edward B. Jorgenson, Mrdfml, 'TREASURER its 57th annual membership meeting at Bruce Buclmayr, Rugur Riwr Terrie Claflin, Phocnix Hanley Farm. It was a great success, Robert Cowling, M'dfml M ichael D onovan, Ash/ami Thanks to all the Society trustees and Yvonne Earnest, Mulford JertS:!. Breo. j ockrmvi& Society Foundation directors, members, John Laughlin, Ash/m,d Judy H. Lozano, BUilt Falls volunteers, and staff who attended. B.J. Reed, Jo(kJonvillt Sandm Slattery, Ash/mId Two outgoing trustees, AI AIsing and Marjorie Overland, were bid farewell, Administra tive Staff John Enders, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR and two incoming trustees, Terrie Maureen Smith, FINANCFJOPERATIONS DIREcroR Wagon rides at the Society's Annual Meeting Susan Musolf, DEVEl.oP;\IEl'oT/PR COORDINATOR Claflin of Phoenix and Sandra Slattery of Ashland, were welcomed to the board, Their terms will begin July 1. Collectio ns/Research Library I Exhib its Staff I want to reiterate something I said during my brief presentation at the meeting about the Steve Wyatt, CURATOR OF COll.ECTIONS Carol Harbison-Samuelson, LIBRARY MANAGER/PHaro ARCHIVIST way the Society looks at its members. -

Mill Valley Oral History Program a Collaboration Between the Mill Valley Historical Society and the Mill Valley Public Library

Mill Valley Oral History Program A collaboration between the Mill Valley Historical Society and the Mill Valley Public Library PAUL LIBERATORE An Oral History Interview Conducted by Debra Schwartz in 2017 © 2017 by the Mill Valley Public Library TITLE: Oral History of Paul Liberatore INTERVIEWER: Debra Schwartz DESCRIPTION: Transcript, 44 pages INTERVIEW DATE: September 5th, 2017 In this oral history, Paul Liberatore recounts his life as a journalist, rock ‘n’ roll writer, and participant-observer in the Marin County music scene over the course of several decades. Born in Yonkers, New York, in 1945, Paul moved to Southern California with his mother and stepfather in the early 1950s, and grew up in Santa Clarita. After graduating from San Diego State University, Paul landed his first newspaper job with the San Diego Union-Tribune. In 1972, Paul moved with his then wife and children up to Marin, and began working for the Marin Independent Journal. He was originally assigned to the Mill Valley Bureau, from which he covered Southern and West Marin. Paul recounts his journalism career over the ensuing decades, which took him to the San Francisco Chronicle for a period, before he returned to the IJ, where he was still working at the time this oral history was recorded. Paul discusses how he became a rock journalist and recalls the various musicians he has written about and — as a guitar player and singer in his own right — played with over the years, evoking the rich history of rock music in Marin County. In 2017, Paul was involved in various events to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love, including a talk and musical performance sponsored by the Mill Valley Historical Society and held at the Library as well as a concert he produced with Jimmy Dillon at the Nourse Theater in San Francisco. -

Jefferson State. the Truck Left, Its Riders Hollering and Shouting Loud Calls of Support for the Action, and Drove Off Towards Yreka

JEFFERSON STATE Kaena Horowitz B.A., Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA, 2006 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HISTORY at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SUMMER 2009 JEFFERSON STATE A Thesis by Kaena Horowitz Approved by: -, Committee Chair Christopher (astaneda, PhD , Committee Chair Erika GassePhD &"- c4. 'd?~ Date LI ii Student: Kaena Horowitz I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. , Department Chair AP - q, 'o0 Christophef Castaneda, PhD V Date Department of History iii Abstract of JEFFERSON STATE by Kaena Horowitz In 1941, counties in northern California and southern Oregon expressed a growing dissatisfaction with their respective governments' inadequate attention to the needs of these communities to either develop their economic infrastructure, nor address the perceived political disparity between rural populations and urban centers. As the lack of assistance led to economic stagnation, these regions could not achieve similar political recognition as their urban counterparts. Thus, these counties united to create Jefferson, a new, independent, more responsive state, hoping to downsizing overburdened state bureaucracies in favor of conceptions of equal representation through popular mandate. This social movement was abandoned in 1941, but the tradition of critical judgment of an unresponsive legislature is memorialized and celebrated in the region today. It is this state of mind that embodies the spirit of Jefferson State and persists in the American ideal of democracy. Committee Chair Christo her Castaneda, PhD A5 Y.d Date iv PREFACE Halfway between Portland, Oregon, and Sacramento, California, by the side of the road, is a large barn with a banner painted across its top declaring the State of Jefferson. -

Frank Rossi of Gino and Carlo's to Retire

CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO EDWIN M. LEE, MAYOR OFFICE OF SMALL BUSINESS REGINA DICK-ENDRIZZI, DIRECTOR Legacy Business Registry Staff Report HEARING DATE MAY 8, 2017 GINO AND CARLO, INC. Application No.: LBR-2016-17-045 Business Name: Gino and Carlo, Inc. Business Address: 548 Green Street District: District 3 Applicant: Marco Rossi, Frank Rossi and Ron Minolli, Owners Nomination Date: December 12, 2016 Nominated By: Supervisor Aaron Peskin Staff Contact: Richard Kurylo [email protected] BUSINESS DESCRIPTION Gino and Carlo, Inc. is a sports bar in the North Beach neighborhood established in 1942 by two friends, Gino and Carlo, to cater to the surrounding working class Italian American community, and more specifically, those who worked the graveyard shift. The business opened at 6 a.m. to serve this niche – a practice that continues today. In 1956, Gino and Carlo sold the business to Donato Rossi and Aldino Cuneo, a famous bocce ball player. Rossi’s brother, Frank Rossi Sr., joined the business in 1968, followed by Ron Minolli who joined a decade later. Today, the business is co-owned by Frank Rossi Jr., Marco Rossi, and Ron Minolli. Over the years, Gino and Carlo initiated numerous traditions and events that provided opportunities for neighborhood residents to come together, including a monthly Thursday Banquet Luncheon, Thanksgiving meals, pedro (an Italian card game) and bocce ball. Memorial services for famous residents of North Beach, such as Joe DiMaggio, Warren Hinckle, and Carol Doda, have been held at the bar, and the business regularly participates in the annual Columbus Day Parade and North Beach Fair.