A Case Study of Phillips Academy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaboration Through Writing and Reading: Exploring Possibilities. INSTITUTION Center for the Study of Writing, Berkeley, CA.: Illinois Univ., Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 450 CS 212 094 AUTHOR Dyson, Anne Haas, Ed. TITLE Collaboration through Writing and Reading: Exploring Possibilities. INSTITUTION Center for the Study of Writing, Berkeley, CA.: Illinois Univ., Urbana. Center for the Study of Reading.; National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0737-0 PUB DATE 89 GRANT OERI-G-00869 NOTE 288p.; Product of a working conference (Berkeley, CA, February 14-16, 1986). AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 07370-3020; $13.95 member, $17.95 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cultural Context; Elementary Secondary Education; English Instruction; Higher Education; *Language Arts; Problem Solving; *Reading Instruction; *Reading Writing Relationship; *Writing Instruction IDENTIFIERS *Collaborative Learning ABSTRACT This book, a series of essays developed at a working conference on the integration of reading and writing, surveys the historical, cultural, situational and social forces that keep the teaching of writing separate, skew the curriculum to favor reading over writing, and discourage development of pedagogies that integrate the language arts; examines the cognitive processes and strategies writers and readers use outside of school to develop and express their ideas; and discusses the challenge teachers face--to help students -

King's Academy

KING’S ACADEMY Madaba, Jordan Associate Head of School for Advancement August 2018 www.kingsacademy.edu.jo/ The Position King’s Academy in Jordan is the realization of King Abdullah’s vision to bring quality independent boarding school education to the Levant as a means of educating the next generation of regional and global leaders and building international collaboration, peace, and understanding. Enrolling 670 students in grades 7-12, King’s Academy offers an educational experience unique in the Middle East—one that emulates the college-preparatory model of American boarding schools while at the same time upholding and honoring a distinctive MISSION Middle Eastern identity. Since the School’s founding in 2007, students from Jordan, throughout the Middle East, and other In a setting that is rich in history nations from around the world have found academic challenge and tradition, King’s Academy and holistic development through King’s Academy’s ambitious is committed to providing academic and co-curricular program, which balances their a comprehensive college- intellectual, physical, creative, and social development. preparatory education through a challenging curriculum in the arts and sciences; an integrated From the outset, King’s Academy embraced a commitment co-curricular program of athletics, to educational accessibility, need-based financial aid, and activities and community service; diversity. Over 40 countries are represented at King’s, and and a nurturing residential approximately 74% of students reside on campus. More than environment. Our students 45% of the student body receives financial aid at King’s, and the will learn to be independent, School offers enrichment programs to reach underprivileged creative and responsible thinkers youth in Jordan (see Signature Programs). -

An Analysis of the Effects of Boarding School on Chinese Students’ Academic Achievement

FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education Vol. 6, Iss. 3, 2020, pp. 36-57 COMPENSATING FOR FAMILY DISADVANTAGE: AN ANALYSIS OF THE EFFECTS OF BOARDING SCHOOL ON CHINESE STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT Minda Tan1 Shandong Normal University, China Katerina Bodovski Pennsylvania State University, USA Abstract China implemented a policy to improve education equity through investing in boarding programs of public schools in rural and less-developed areas. However, this policy has not been informed by empirical research in the Chinese context. By using the nationally representative longitudinal data, this study investigates whether and to what extent boarding schools compensate for children's family disadvantages in terms of mathematics and reading achievement. The findings, drawn from multilevel logistic regression and hierarchical models, indicate that students from low-SES families or rural areas tend to board at schools. Boarding students performed better than day students in 8th-grade mathematics tests. Among students with essential needs, those residing at school during the week significantly benefitted in their school performance in both subjects. Overall, it appears that governmental investment in boarding programs can, to some extent, compensate for some family disadvantages. Keywords: boarding school; academic performance; socioeconomic status; family support; education equity 1 Correspondence: Minda Tan, 88 Wenhuadong Road, Shandong Normal University, 250014, Jinan, Shandong Province, China; Email: [email protected] M. Tan & K. Bodovksi 37 Introduction Family educational resources are unequally allocated among families within countries. In China, students from socioeconomically disadvantaged families are challenged to achieve academic success similar to that of their peers because their parents cannot provide adequate financial and cultural resources (Luo & Zhang, 2017) . -

The Potential of Urban Boarding Schools for the Poor: Evidence from SEED∗

The Potential of Urban Boarding Schools for the Poor: Evidence from SEED∗ Vilsa E. Curtoy Roland G. Fryer, Jr.z October 14, 2012 Abstract The SEED schools, which combine a \No Excuses" charter model with a five-day-a-week boarding program, are America's only urban public boarding schools for the poor. We provide the first causal estimate of the impact of attending SEED schools on academic achievement, with the goal of understanding whether changing both a student's social and educational en- vironment through boarding is an effective strategy to increase achievement among the poor. Using admission lotteries, we show that attending a SEED school increases achievement by 0.211 standard deviations in reading and 0.229 standard deviations in math, per year of attendance. Subgroup analyses show that the eff ects are entirely driven by female students. We argue that the large impacts on reading are consistent with dialectical theories of language development. ∗We are grateful to Eric Adler, Anjali Bhatt, Pyper Davis and Rajiv Vinnakota for their cooperation in collect- ing data necessary for this project. Matt Davis, Will Dobbie, and Meghan Howard provided exceptional research assistance. Support from the Education Innovation Laboratory at Harvard University (EdLabs) is gratefully ac- knowledged. Correspondence can be addressed to either of the authors by mail: Department of Economics, Harvard University, 1805 Cambridge Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 [Fryer]; Department of Economics, Stanford University, 579 Serra Mall, Stanford, CA 94305 [Curto]; or by email: [email protected] [Fryer] and [email protected] [Curto]. The usual caveat applies. yStanford University zRobert M. -

The Next-Gen Boarding School

global boarding – washington, dc global boarding – washington, THE NEXT-GEN BOARDING SCHOOL Washington, DC THE FIRST GLOBAL BOARDING SCHOOL WASHINGTON, DC • SHENZHEN whittle school SUZHOU • BROOKLYN, NY & studios www.whittleschool.org [email protected] +1 (202) 417-3615 THE FIRST GLOBAL BOARDING SCHOOL WASHINGTON, DC • SHENZHEN SUZHOU • BROOKLYN, NY www.whittleschool.org [email protected] +1 (202) 417-3615 global boarding 1 SHENZHEN, CHINA WASHINGTON, DC One School. Around the World. BROOKLYN, NY SUZHOU, CHINA 2 whittleschool.org global boarding 3 4 whittleschool.org global boarding 5 The Story of Whittle A Global Collaboration to Transform Education We aim to create an extraordinary and unique school, the first truly modern institution serving children from ages three to 18 and the first global one. We want to change for the better the lives of those students who attend and, beyond our own campuses, contribute to the cause of education on every continent. We measure our merit not through the narrowness of exclusivity but through the breadth of our impact. In the fall of 2019, we opened our first two campuses simultaneously in Washington, DC and Shenzhen, China — and soon after announced our next campuses to open in Brooklyn, New York (later this year) and Suzhou, China (in the fall of 2021). 6 whittleschool.org global boarding 7 Introducing The Next - Generation Boarding School Boarding lies at the heart of some of the world’s greatest schools. There is good reason for this: The opportunity to live in a learning community, to A global school with opportunities to form lasting friendships, and to develop confidence and independence when away from home can be life changing. -

Dual County League

Central (Leslie C) Dual County League: Acton Boxborough Regional High School, Bedford High School, Concord Carlisle High School, Lincoln Sudbury Regional High School, Wayland High School, Weston High School, Westford High School (7 schools) Central League: Advanced Math and Science Academy Auburn High School Assabet Valley Tech Regional High School Baypath Regional Vocational Tech High School Blackstone Valley Tech, Doherty Worcester Public Schools Grafton High School Nipmuc High School Northbridge High School Montachusett Reg Vocational Tech School, Fitchburg Nashoba Valley Tech, Westford, MA St. Bernard High School St. Peter Marion High School Notre Dame Academy Worcester (13 Schools) Mid Wachusett League: Algonquin Regional High School, Bromfield High School, Fitchburg High School, Groton Dunstable High School, Hudson High School, Leominster High School, Littleton High School, Lunenburg High School, Marlborough High School, Nashoba Regional High School, North Middlesex Regional High School, Oakmont Regional High School, Shepherd Hill Regional High School, Shrewsbury High School, Tahanto Regional High School, Tyngsborough Regional High School, Wachusett Regional High School, Westborough High School (18 Schools) Independent Eastern League (IEL): Bancroft School (Worcester), Concord Academy (Concord) (2) Independent School League (ISL): Concord Academy, Cushing Academy, Groton School, Lawrence Academy, Middlesex School, Rivers School, St. Mark’s School (8 Schools) Private School Programs: Applewild School (Fitchburg), Charles River School (Dover), Fay School (Southboro), Nashoba Brooks School (Concord), Meadowbrook School (Weston), Winchendon Academy (Winchendon), Worcester Academy (Worcester) (7 Schools) (55 Schools Total) . -

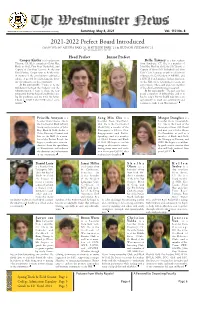

2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced - - - Times

Westminster School Simsbury, CT 06070 www.westminster-school.org Saturday, May 8, 2021 Vol. 110 No. 8 2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced COMPILED BY ALEYNA BAKI ‘21, MATTHEW PARK ‘21 & HUDSON STEDMAN ‘21 CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF, 2020-2021 Head Prefect Junior Prefect Cooper Kistler is a boarder from Bella Tawney is a day student Tiburon, CA. He is a member of John Hay, from Simsbury, CT. She is a member of Black & Gold, First Boys’ Basketball, and John Hay, Black & Gold, the SAC Board, a Captain of First Boys’ lacrosse. As the new Captain of First Girls’ Basketball and First Head Prefect, Cooper aims to be the voice Girls’ Cross Country, as well as a Horizons of everyone in the community to cultivate a volunteer, the Co-President of AWARE, and culture of growth by celebrating the diver- a HOTH board member. In her final year sity of perspectives in the community. on the Hill, she is determined to create an In his own words: “I want to be the environment, where each and every member middleman between the Students and the of the school community feels accepted. Administration. I want to share the new In her own words: “The past year has perspective that we have all established dur- posed a number of difficulties, and it is ing the pandemic, and use it for the better. hard to adapt, but we should take this as an I want to UNITE the NEW school com- opportunity to teach our community and munity." continue to make it our Westminster." Priscilla Ameyaw is a Sung Min Cho is a Margot Douglass is a boarder from Ghana. -

School Brochure

Bring Global Diversity to Your Campus with ASSIST 52 COUNTRIES · 5,210 ALUMNI · ONE FAMILY OUR MISSION ASSIST creates life-changing opportunities for outstanding international scholars to learn from and contribute to the finest American independent secondary schools. Our Vision WE BELIEVE that connecting future American leaders with future “Honestly, she made me think leaders of other nations makes a substantial contribution toward about the majority of our texts in brand new ways, and increasing understanding and respect. International outreach I constantly found myself begins with individual relationships—relationships born taking notes on what she through a year of academic and cultural immersion designed would say, knowing that I to affect peers, teachers, friends, family members and business would use these notes in my teaching of the course associates for a lifetime. next year.” WE BELIEVE that now, more than ever, nurturing humane leaders “Every time I teach this course, there is at least one student through cross-cultural interchange affords a unique opportunity in my class who keeps me to influence the course of future world events in a positive honest. This year, it’s Carlota.” direction. “Truly, Carlota ranks among the very best of all of the students I have had the opportunity to work with during my nearly 20 years at Hotchkiss.” ASSIST is a nonprofit organization that works closely with American independent secondary Faculty members schools to achieve their global education and diversity objectives. We identify, match The Hotchkiss School and support academically talented, multilingual international students with our member Connecticut schools. During a one-year school stay, an ASSIST scholar-leader serves as a cultural ambassador actively participating in classes and extracurricular activities. -

Will Rogers and Calvin Coolidge

Summer 1972 VoL. 40 No. 3 The GfJROCEEDINGS of the VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY Beyond Humor: Will Rogers And Calvin Coolidge By H. L. MEREDITH N August, 1923, after Warren G. Harding's death, Calvin Coolidge I became President of the United States. For the next six years Coo lidge headed a nation which enjoyed amazing economic growth and relative peace. His administration progressed in the midst of a decade when material prosperity contributed heavily in changing the nature of the country. Coolidge's presidency was transitional in other respects, resting a bit uncomfortably between the passions of the World War I period and the Great Depression of the I 930's. It seems clear that Coolidge acted as a central figure in much of this transition, but the degree to which he was a causal agent, a catalyst, or simply the victim of forces of change remains a question that has prompted a wide range of historical opinion. Few prominent figures in United States history remain as difficult to understand as Calvin Coolidge. An agrarian bias prevails in :nuch of the historical writing on Coolidge. Unable to see much virtue or integrity in the Republican administrations of the twenties, many historians and friends of the farmers followed interpretations made by William Allen White. These picture Coolidge as essentially an unimaginative enemy of the farmer and a fumbling sphinx. They stem largely from White's two biographical studies; Calvin Coolidge, The Man Who Is President and A Puritan in Babylon, The Story of Calvin Coolidge. 1 Most notably, two historians with the same Midwestern background as White, Gilbert C. -

BISCCA Boston Independent School College Counselors Association

BISCCA Boston Independent School College Counselors Association Bancroft School ● Beaver Country Day School ● Belmont Hill School ● Boston Trinity Academy ● Boston University Academy ● Brimmer & May School ● Brooks School ● Buckingham Browne & Nichols School ● Cambridge School of Weston ● Chapel Hill-Chauncy Hall School ● Commonwealth School ● Concord Academy ● Cushing Academy ● Dana Hall School ● Dexter Southfield School ● GANN Academy ● The Governor’s Academy ● Groton School ● International School Of Boston ● Lawrence Academy ● Maimonides School ● Middlesex School ● Milton Academy ● Newton Country Day School ● Noble & Greenough School ● Pingree School ● Rivers School ● Roxbury Latin School ● St. Mark’s School ● St. Sebastian’s School ● Tabor Academy ● Thayer Academy ● Walnut Hill School ● Winsor School ● Worcester Academy BISCCA Webinar Series Navigating the Waters: Tips for Transitioning to College for the Class of 2020 BISCCA has invited four of the leading voices in college admissions to offer brief commentaries on the state of affairs in higher education and college admission for the Class of 2020, which will then be followed by a question and answer session, covering a range of important topics. Date: Tuesday, May 19th Time: 7:00 to 8:15 PM Panelists: • Chris Gruber, Vice President, Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid, Davidson College • Joy St. John, Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid, Wellesley College • Matt Malatesta, Vice President for Admissions, Financial Aid and Enrollment, Union College • Whiney Soule, Senior Vice President, Dean of Admissions and Student Aid, Bowdoin College Moderators: • Tim Cheney, Director of College Counseling, Tabor Academy • Amy Selinger, Director of College Counseling, Buckingham Browne & Nichols School • Matthew DeGreeff, Dean of College Counseling & Student Enrichment, Middlesex School Please fill out this Pre-Webinar Survey so we can alert our panelists to topics of interest, questions, and their importance to your family. -

Andover, M.Ll\.Ss.Ll\.Chusetts

ANDOVER, M.LL\.SS.LL\.CHUSETTS PROCEEDINGS AT THE CELEBRATION OF THE OF THE I NCO RPO RATION OF THE TOvVN ANDOVER, MASS. THE ANDOVER PRESS 1897 -~ ~ NDOVER Massachu setts Book of Proceed- ~~--ings at the Celebration of the Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of theTown's Incor poration 1646-1896~~~~~ CONTENTS ACTION AT To,vN MEETING, MARCH, 1894, 13 FIRST ANNUAL REPORT OF COMMITTEE OF FIFTEEN, 14 SECOND ANNUAL REPORT OF COMMITTEE OF FIFTEEN, 15 THIRD ANNUAL REPORT OF COMMITTEE OF FIFTEEN, 19 FINANCIAL STATEMENT, 22 COMMITTEES, 23 INVITED GUESTS, 26 OFFICIAL PROGRAM, 29 SUNDAY AT THE CHURCHES, 31 HISTORICAL TABLEAUX, 34 THE PROCESSION, 37 CHILDREN'S ENTERTAINMENT, 40 THE SPORTS, 41 BAND CONCERTS, 42 ORATION, BY ALBERT POOR, ESQ., 43 PoEM, BY MRS. ANNIE SA\VYER DowNs, READ BY PROF. JOHN W. CHURCHILL, 96 ADDRESS OF THE PRESIDENT, PROF. J. w. CHURCHILL, 115 ADDRESS OF ACTING GOVERNOR ROGER WOLCOTT, I 16 ADDRESS OF HoN. WILLIAM S. KNox, 120 SENTIMENT FROM HoN. GEORGE 0. SHATTUCK, 122 TELEGRAM FROM REV. DR. WILLIAM JEWETT TUCKER, 123 ADDRESS OF HOLLIS R. BAILEY, ESQ., 123 ADDRESS OF CAPT. FRANCIS H. APPLETON, 127 ADDRESS OF HoN. MosEs T. STEVENS, 129 ADDRESS OF CAPT. JORN G. B. ADAMS, 1 34 ADDRESS OF ALBERT POOR, ESQ., 136 SENTIMENT FROM MRS. ANN!E SAWYER DOWNS, 138 ADDRESS OF PROF. JOHN PHELPS TAYLOR, 138 Boan Cot teetion attb ijistorie ~ites REPORT OF COMMITTEE, 144 PORTRAITS AND PICTURES OF ANDOVER MEN AND WOMEN, 146 PHILLIPS ACADEMY, I 55 ANDOVER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, I 56 ABBOT ACADEMY, 157 PUNCHARD FREE SCHOOL, 158 MEMORIAL HALL LH''R ~.. -

A History of Legal Specialization

South Carolina Law Review Volume 45 Issue 5 Conference on the Commercialization Article 17 of the Legal Profession 5-1993 Know the Law: A History of Legal Specialization Michael S. Ariens St. Mary's University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ariens, Michael S. (1993) "Know the Law: A History of Legal Specialization," South Carolina Law Review: Vol. 45 : Iss. 5 , Article 17. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr/vol45/iss5/17 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ariens:KNOW Know the THE Law: ALAW: History of A Legal HISTORY Specialization OF LEGAL SPECIALIZATION MICHAEL ARIENS I. INTRODUCTION .............................. 1003 II. THE AUTHORITY OF LAWYERS ..................... 1011 M. A HISTORY OF SPECIALIZATION .................... 1015 A. The Changing of the Bar: 1870-1900 .............. 1015 B. The Business of Lawyers: 1900-1945 .............. 1022 C. The Administrative State and the Practice of Law: 1945-69 1042 D. The End of the Beginning: 1970-Present ............ 1054 IV. CONCLUSION ............................... 1060 I. INTRODUCTION In 1991, Victoria A. Stewart sued her former employer, the law firm of Jackson & Nash, claiming that it negligently misrepresented itself and fraudulently induced her to join the firm. Stewart claimed that she joined Jackson-& Nash after being told that the firm had been hired by a major client for assistance with environmental law issues and that she would manage the firm's environmental law department.