Majid Khan 2012 V3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEAK PERFORMANCE AGE: a DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS of PAKISTAN TEST BATSMEN Imran Abbass

PEAK PERFORMANCE AGE: A DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS OF PAKISTAN TEST BATSMEN Imran Abbass ABSTRACT The study intended to explore the relationship of age and performance of test batsmen to know at what age they achieved the peak performance while playing test cricket. Qualitative data was collected through interviews and Secondary data sources were used of different ICC (International Cricket Council) websites and magazines. Sample comprised of top 12 test players of Pakistan from past and present era, who played for Pakistan with distinction. Time series and regression analysis was executed to find the significance of the relationship between their age and performance (Batting average).The findings of the study revealed a parabolic trajectory relationship between age and their performance, positive relationship at the start and then a plateau and then a negative relationship between age and performance. The rise and decline pattern varied and majority of the cricket players touched the peak between the ages of 28 to 34 years. The current study will provide solid grounds to account the role of age in producing expert performance and strongly suggested through the evidence of data analysis that to achieve the expert performance of the enrolled test batsmen, patience is required until and unless the cricket players meet a specific age limit. Key Words: Cricket, Test Batsmen, Peak Performance, Age INTRODUCTION score of 23, Aamer nicked one to On a bright sunny morning of the Bacher in the slips and in 1997-98 winters, stage was set to adding four runs Pakistan top topple the mighty South Africans four batsman were gone to the at eastern shores. -

RESTRUCTURING FIRST CLASS CRICKET Majid Khan Former Pakistan Test Captain Bazid Khan Former Pakistan Test Cricketer FOCUS

RESTRUCTURING FIRST CLASS CRICKET Majid Khan Former Pakistan Test Captain Bazid Khan Former Pakistan Test Cricketer FOCUS Primarily Changed Role District & For Departments Division Based First Class Cricket STAKEHOLDERS Governing Authority Pakistan Cricket Players Board Divisions (Districts) Public Co-Operate Sector Sponsors DEMOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Eleven Divisions Each Division to First Class Season (Cricket Playing) in Comprise of 4 to start in October First Class Cricket Districts and ends in March So all Districts Districts to play 12 within a Division home and 12 away playing 24 matches matches in a season District Cricket To be the Feeder Divisions to play Stock for the Division Districts (3 day First Class Cricket matches) team Each Division plays 10 First Class First Class Matches Matches (5 home & 5 Away) spread over 4 day duration six months NON FIRST CLASS DIVISIONS Similar Set Up for Non First 4 Districts in Each Division Class Divisions Divisions Districts playing 24 10 matches matches in six months (5 home & 5 away) 12 home and 12 away Non First Class 2 day matches 3 day matches DIVISION SECRETARIATS HR to include Coaches (First Class CEO to be a former International/ First Class Cricketers) Cricketer (to be enrolled through open advertisement and with a pre-defined criteria Trainers (to be hired during the Executive Committee to include an Executive season) Member from the Franchise/Departments as Selectors (First Class Cricketers) an equal stake holder Treasurer/Finance/Sales Electoral College to include Public (Memberships -

P15-Sports Layout 1

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 3, 2014 SPORTS Mura wins Skate Canada Australia beat England Cricket great almost quit KELOWNA: Japan’s Takahito Mura won the Skate Canada International men’s title 16-12 in 4 Nations Champs NEW DELHI: Cricket great Sachin Tendulkar considered early retirement Saturday, landing two quadruple jumps and finishing with 255.81 points. Mura was after a string of losses while India’s captain, according to excerpts from the in tears and buried his head in a towel after his marks went up. “I was a little bit sur- MELBOURNE: Australia denied England a potentially match-winning try record-holding batsman’s upcoming autobiography. prised how well I was able to do, until now I was lacking a bit of confidence,” Mura in the final minute for a 16-12 win in rugby league’s Four Nations “I hated losing and as captain of the team I felt responsible for the string said through an interpreter. “While I was skating, I was thinking, ‘I’m doing really Championship yesterday, keeping alive its title defense. of miserable performances. More worryingly, I did not know how I could great. Very comfortable.’” Spain’s Javier Fernandez, the leader after the short program, Center Ryan Hall, who had already scored one of the two tries that turn it around, as I was already trying my absolute best,” Tendulkar wrote in dropped to second with 244.87 points. He had trouble on his three quad attempts, gave England a 12-4 halftime lead, hurled himself at a ball over the extracts of the book “Playing It My Way,” published by the Press Trust of falling on one of them. -

Hearing for Majid Khan

C05403115 o (b)(1) (b)(3) Verbatim Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribnnal Hearing for ISN 10020 OPENING PRESIDENT: This hearing shall come to order. RECORDER: This Tribunal is being conducted at 08:42 on 15 April 2007 on board U.S. Naval Base Guantanarno Bay, Cuba. The following personnel are present: Colonel United States Air Force, President, Commander United States Navy, Member, Lieutenant Colonel United States Air Force, Member, Major United States Air Force, Personal Representative, Sergeant First Class United States Army, Reporter, Major_United States Air Force, Recorder. Lieutenant Colonel_is the Judge Advocate member ofthe Tribunal. OATH SESSION 1 RECORDER: All rise. PRESIDENT: The Recorder will be sworn. Do you, Major-swear or affirm that you will faithfully perform the duties as ~signed in this Tribunal, so help you God? RECORDER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Reporter will now be sworn. The Recorder will administer the oath. RECORDER: Do you, Sergeant First Class swear that you will faithfully discharge your duties as Reporter assigned in this Tribunal, so help you God? REPORTER: [ do. PRESIDENT: We'll take a briefrecess while the Detainee is brought into the room. RECORDER: The time is 08:43 on IS Apri12007. This Tribunal is now in recess. All rise. [All personnel depart the room.] CONVENING AUTHORITY RECORDER: [All personnel return into the room at 08:48.] All rise. PRESIDENT: This hearing will come to order. You may be seated. Good morning. DETAINEE: Good morning. How are you guys doing? ISN # 10020 Enclosure (3) Page1 of50 C05403115 PRESIDENT: Very good, fine, thank you. This Tribunal is convened by order ofthe Director, Combatant Status Review Tribunals under the provisions ofhis Order of 12 February 2007. -

True and False Confessions: the Efficacy of Torture and Brutal

Chapter 7 True and False Confessions The Efficacy of Torture and Brutal Interrogations Central to the debate on the use of “enhanced” interrogation techniques is the question of whether those techniques are effective in gaining intelligence. If the techniques are the only way to get actionable intelligence that prevents terrorist attacks, their use presents a moral dilemma for some. On the other hand, if brutality does not produce useful intelligence — that is, it is not better at getting information than other methods — the debate is moot. This chapter focuses on the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation technique program. There are far fewer people who defend brutal interrogations by the military. Most of the military’s mistreatment of captives was not authorized in detail at high levels, and some was entirely unauthorized. Many military captives were either foot soldiers or were entirely innocent, and had no valuable intelligence to reveal. Many of the perpetrators of abuse in the military were young interrogators with limited training and experience, or were not interrogators at all. The officials who authorized the CIA’s interrogation program have consistently maintained that it produced useful intelligence, led to the capture of terrorist suspects, disrupted terrorist attacks, and saved American lives. Vice President Dick Cheney, in a 2009 speech, stated that the enhanced interrogation of captives “prevented the violent death of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of innocent people.” President George W. Bush similarly stated in his memoirs that “[t]he CIA interrogation program saved lives,” and “helped break up plots to attack military and diplomatic facilities abroad, Heathrow Airport and Canary Wharf in London, and multiple targets in the United States.” John Brennan, President Obama’s recent nominee for CIA director, said, of the CIA’s program in a televised interview in 2007, “[t]here [has] been a lot of information that has come out from these interrogation procedures. -

Justice Qayyum's Report

PART I BACKGROUND TO INQUIRY 1. Cricket has always put itself forth as a gentleman’s game. However, this aspect of the game has come under strain time and again, sadly with increasing regularity. From BodyLine to Trevor Chappel bowling under-arm, from sledging to ball tampering, instances of gamesmanship have been on the rise. Instances of sportsmanship like Courtney Walsh refusing to run out a Pakistani batsman for backing up too soon in a crucial match of the 1987 World Cup; Imran Khan, as Captain calling back his counterpart Kris Srikanth to bat again after the latter was annoyed with the decision of the umpire; batsmen like Majid Khan walking if they knew they were out; are becoming rarer yet. Now, with the massive influx of money and sheer increase in number of matches played, cricket has become big business. Now like other sports before it (Baseball (the Chicago ‘Black-Sox’ against the Cincinnati Reds in the 1919 World Series), Football (allegations against Bruce Grobelar; lights going out at the Valley, home of Charlton Football club)) Cricket Inquiry Report Page 1 Cricket faces the threat of match-fixing, the most serious threat the game has faced in its life. 2. Match-fixing is an international threat. It is quite possibly an international reality too. Donald Topley, a former county cricketer, wrote in the Sunday Mirror in 1994 that in a county match between Essex and Lancashire in 1991 Season, both the teams were heavily paid to fix the match. Time and again, former and present cricketers (e.g. Manoj Prabhakar going into pre-mature retirement and alleging match-fixing against the Indian team; the Indian Team refusing to play against Pakistan at Sharjah after their loss in the Wills Trophy 1991 claiming matches there were fixed) accused different teams of match-fixing. -

Homeland Security Implications of Radicalization

THE HOMELAND SECURITY IMPLICATIONS OF RADICALIZATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 20, 2006 Serial No. 109–104 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35–626 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman DON YOUNG, Alaska BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas LORETTA SANCHEZ, California CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut NORMAN D. DICKS, Washington JOHN LINDER, Georgia JANE HARMAN, California MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon TOM DAVIS, Virginia NITA M. LOWEY, New York DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM GIBBONS, Nevada Columbia ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut ZOE LOFGREN, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON-LEE, Texas STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey KATHERINE HARRIS, Florida DONNA M. CHRISTENSEN, U.S. Virgin Islands BOBBY JINDAL, Louisiana BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina DAVE G. REICHERT, Washington JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MICHAEL MCCAUL, Texas KENDRICK B. MEEK, Florida CHARLIE DENT, Pennsylvania GINNY BROWN-WAITE, Florida SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut, Chairman CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania ZOE LOFGREN, California MARK E. -

Requests Report

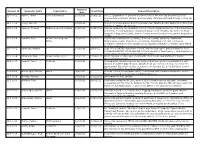

Received Request ID Requester Name Organization Closed Date Request Description Date 12-F-0001 Vahter, Tarmo Eesti Ajalehed AS 10/3/2011 3/19/2012 All U.S. Department of Defense documents about the meeting between Estonian president Arnold Ruutel (Ruutel) and Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney on July 19, 1991. 12-F-0002 Jeung, Michelle - 10/3/2011 - Copies of correspondence from Congresswoman Shelley Berkley and/or her office from January 1, 1999 to the present. 12-F-0003 Lemmer, Thomas McKenna Long & Aldridge 10/3/2011 11/22/2011 Records relating to the regulatory history of the following provisions of the Department of Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), the former Defense Acquisition Regulation (DAR), and the former Armed Services Procurement Regulation (ASPR). 12-F-0004 Tambini, Peter Weitz Luxenberg Law 10/3/2011 12/12/2011 Documents relating to the purchase, delivery, testing, sampling, installation, Office maintenance, repair, abatement, conversion, demolition, removal of asbestos containing materials and/or equipment incorporating asbestos-containing parts within its in the Pentagon. 12-F-0005 Ravnitzky, Michael - 10/3/2011 2/9/2012 Copy of the contract statement of work, and the final report and presentation from Contract MDA9720110005 awarded to the University of New Mexico. I would prefer to receive these documents electronically if possible. 12-F-0006 Claybrook, Rick Crowell & Moring LLP 10/3/2011 12/29/2011 All interagency or other agreements with effect to use USA Staffing for human resources management. 12-F-0007 Leopold, Jason Truthout 10/4/2011 - All documents revolving around the decision that was made to administer the anti- malarial drug MEFLOQUINE (aka LARIAM) to all war on terror detainees held at the Guantanamo Bay prison facility as stated in the January 23, 2002, Infection Control Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). -

Military Commissions: a Place Outside the Law’S Reach

MILITARY COMMISSIONS: A PLACE OUTSIDE THE LAW’S REACH JANET COOPER ALEXANDER* “We have turned our backs on the law and created what we believed was a place outside the law’s reach.” Colonel Morris D. Davis, former chief prosecutor of the Guantánamo military commissions1 Ten years after 9/11, it is hard to remember that the decision to treat the attacks as the trigger for taking the country to a state of war was not inevitable. Previous acts of terrorism had been investigated and prosecuted as crimes, even when they were carried out or planned by al Qaeda.2 But on September 12, 2001, President Bush pronounced the attacks “acts of war,”3 and he repeatedly defined himself as a “war president.”4 The war * Frederick I. Richman Professor of Law, Stanford Law School. I would like to thank participants at the 2011 Childress Lecture at Saint Louis University School of Law and a Stanford Law School faculty workshop for their comments, and Nicolas Martinez for invaluable research assistance. 1 Ed Vulliamy, Ten Years On, Former Chief Prosecutor at Guantanamo Slams ‘Camp of Torture,’ OBSERVER, Oct. 30, 2011, at 29. 2 Previous al Qaeda attacks that were prosecuted as crimes include the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center, the Manila Air (or Bojinka) plot to blow up a dozen jumbo jets, and the 1998 embassy bombings in East Africa. Mary Jo White, Prosecuting Terrorism in New York, MIDDLE E.Q., Spring 2001, at 11, 11–14; see also Christopher S. Wren, U.S. Jury Convicts 3 in a Conspiracy to Bomb Airliners, N.Y. -

Australia V Pakistan 1978/79 2Nd Test Perth (WACA). Test: 850 Australia Won by 7 Wickets

Australia v Pakistan 1978/79 2nd Test Perth (WACA). Test: 850 Australia won by 7 wickets. Test in Australia: 198 D Close of play Not out batsmen Day Runs Wk Ov Min Crowd Toss: Australia 1 Pa 240/7 (61ov.) Javed Miandad 112, Sarfraz Nawaz 8 240 7 61 8,550 24-Mar-1979 Umpires: AR Crafter, MG O'Connell 2 Pa 277, Au 180/3 (44ov.) AR Border 34, JK Moss 11 217 6 61 6,780 25-Mar-1979 12th Man: 3 Au 327, Pa 19/1 (6ov.) Mudassar Nazar 9, Zaheer Abbas 9 166 8 58 2,668 26-Mar-1979 TJ Laughlin (Au); Mohsin Khan (Pa) 4 Pa 246/7 (75ov.) Asif Iqbal 101, Sarfraz Nawaz 0 227 6 69 1,971 28-Mar-1979 5 Pa 285, Au 236/3 275 6 59 1,878 29-Mar-1979 TOTALS 1125 33 307 1749 21,847 Scorers: E McMullan; AJ Nicholls Test # PAKISTAN 1st Innings R M 4,6 BF Fall of Wickets Ov M R W nb,w 6s 44 Majid Khan c-4s Hilditch b Hogg 0 1 0,- 2 R Mins RM Hogg 19 2 88 1 0,0 1 11 Mudassar Nazar cwk Wright b Hurst 5 42 0,- 35 1-0 0 1 M Khan/M Naz 0 AG Hurst 23 4 61 4 1,3 - 33 Zaheer Abbas cwk Wright b Hurst 29 60 3,- 35 2-27 27 40 M Naz/Z Abb 19 G Dymock 21.6 4 65 3 4,0 - 21 Javed Miandad not out 129 388 15,- 275 3-41 14 18 Z Abb/J Mia 3 B Yardley 14 2 52 0 0,0 - 14 Haroon Rashid c-3s Border b Hurst 4 9 1,- 4 4-49 8 9 H Ras/J Mia 7 52 Asif Iqbal run out (Darling) 35 45 5,- 45 5-90 41 45 A Iqb/J Mia 12 57,c19 Mushtaq Mohammad run out (Darling) 23 140 3,- 110 6-176 86 140 M Moh/J Mia 71 22 Imran Khan cwk Wright b Dymock 14 50 0,1 33 7-224 48 50 I Khan/J Mia 104 34 Sarfraz Nawaz cwk Wright b Hurst 27 111 4,- 80 8-276 52 111 S Naw/J Mia 128 50 Wasim Bari c-? Hilditch b Dymock 0 6 0,- -

View Issue As

national lawyers guild Volume 68 Number 4 Winter 2011 Turn to the Constitution in 193 Prayer: Freedom from Religion Foundation v. Obama, the Constitutionality and the Politics of the National Day of Prayer Gail Schnitzer Eisenberg Anatomy of a “Terrorism” 234 Prosecution: Dr. Rafil Dhafir and the Help the Needy Muslim Charity Case Katherine Hughes The National Defense 247 Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012: Battlefield Earth Nathan Goetting editor’s preface On April 17, 1952, with the U.S. nearly two years into the bloody “police action” against the “Godless Communists” in Korea and Tailgunner Joe McCarthy at the height of his foaming and fulminating power in the Sen- ate, President Truman signed into law a bill requiring presidents to exhort Americans to do the one thing the First Amendment seems most emphatic the federal government should never ask citizens to do—pray. The law establish- ing the National Day of Prayer was the result of a mass effort of evangelical Christians, such as Billy Graham, who rallied support for it during one of his “crusades,” to use the organs of government and the bully pulpit of the presidency to aid them in their effort to further Christianize the nation. After a push by the doddering Senator Strom Thurmond from South Carolina, who for decades expressed a uniquely southern zeal for God matched only by his uniquely southern zeal for racial segregation, the law was amended in 1988 so that the National Day of Prayer would be fixed on the first Thursday of every May. It has since become a jealously guarded and zealously promoted evangelical holiday of the politically active Christian right, who use it to perpetuate the false and self-serving narrative that a nation whose founding documents were drafted largely by Enlightenment-era skeptics and deists was actually designed by a council of holy men to be an Augustinian City of God. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Kamran Ahmad Khan Permanent Address: Mir Hashim Khojari Babar P/O Kakki Tehsil & District Bannu K.P.K Pakistan Contact No: +92-03229821869 E-mail: [email protected] Personal Information Father’s Name : Dilawar Khan Date of Birth : April 7, 1981. Domicile : Bannu (K.P.K) Nationality : Pakistani N.I.C # : 11101-1431365-3 Gender : Male Marital Status : Married Designation : Lecturer (BPS-18) Postal Address : Faculty of Pharmacy Gomal University D.I.Khan (K.P.K) Pakistan. Educational Qualifications: Marks Exams Division Year Board/University Obtained S.S.C 625/850 1st 1996 B.I.S.E Bannu F. Sc 770/1100 1st 1999 B.I.S.E Bannu B. Pharmacy 2756/3800 1st 2003 Gomal University D.I.Khan (3rd Position) M. Phil (Pharmaceutics) 3.916 1st 2009 Gomal University D.I.Khan CGPA PhD: (Thesis (3.5GPA) in Course Work Gomal University D.I.Khan Submitted) Professional Experience: Name &Address of Post Date(month/year) S. No Organization/institution Held From To Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Ltd 1. Trainee 09/ 08/2004 15/09/2004 Landhi P.O.Box 7229 Karachi-74400 Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Ltd Territory 1. 17/ 09/2004 1/ 09/2006 Landhi P.O.Box 7229 Karachi-74400 Manager Faculty of Pharmacy Gomal University 2 Lecturer 04/12/2008 Till to Date D.I.Khan Conferences Attended: 1. Ist Training Workshop in Pharmacy held in faculty of Pharmacy G.U.D.I.K. 2. International conference of Pakistan pharmacist association held in Lahore 3. International Chemistry Conference at Gomal University D.I.Khan. 4.