Rabbit & Muskrat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Areas32 State Areas33

NEBRASKA : THE COR NHUSKER STATE 43 larger cities and counties continue to grow. Between 2000 and 2010, the population of Douglas County—home of Omaha—increased 11.5 percent, while neighboring Sarpy County grew 29.6 percent. Nebraska’s population is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. The most significant growth has occurred in the Latino population, which is now the state’s largest minority group. From 2000 to 2010, the state’s Latino population increased from 5.5 percent to 9.2 percent, growing at a rate of slightly more than 77 percent. The black population also grew from 3.9 percent to 4.4 percent during that time. While Nebraska’s median age increased from 35.3 in 2000, to 36.2 in 2010 — the number of Nebraskans age 65 and older decreased slightly during the same time period, from 13.6 percent in 2000, to 13.5 percent in 2010. RECREATION AND PLACES OF INTEREST31 National Areas32 Nebraska has two national forest areas with hand-planted trees: the Bessey Ranger District of the Nebraska National Forest in Blaine and Thomas counties, and the Samuel R. McKelvie National Forest in Cherry County. The Pine Ridge Ranger District of the Nebraska National Forest in Dawes and Sioux counties contains native ponderosa pine trees. The U.S. Forest Service also administers the Oglala National Grassland in northwest Nebraska. Within it is Toadstool Geologic Park, a moonscape of eroded badlands containing fossil trackways that are 30 million years old. The Hudson-Meng Bison Bonebed, an archaeological site containing the remains of more than 600 pre- historic bison, also is located within the grassland. -

Nebraska Museums Association 7/7/11 6:17 PM

Nebraska Museums Association 7/7/11 6:17 PM Home Nebraska Museums About NMA Board of Directors History Membership Nebraska Museums Upcoming Events and Programs Publications Awards Exhibits for Travel Click on the region you are interested in to see the listing for that region. All regions have a printable list. Links (All museums/attractions listed in white with an asterisk are members of the Nebraska Museums Association.) Northeast (Click here for printable version.) Antelope County Historical Society 509 L Street, Hwy 275 Neligh, NE 68756 http://www.jailmuseum.net Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park * 86930 517 Avenue Royal, NE 68773 http://ashfall.unl.edu/ Elgin Historical Society 360 Park Street Elgin, NE 68636-0161 Neligh Mill State Historic Site N Street & Wylie Drive Neligh, NE 68756-0271 http://www.nebraskahistory.org/sites/mill/index.htm Orchard Historical Society 225 Windom Street Orchard, NE 68764 http://www.nebraskaandyou.com/OrchardPlanner.html Boone County Historical Society * 1025 W. Fairview Albion, NE 68620 Rae Valley Heritage Association 1249 State Hwy. 14 Petersburg, NE 68652 http://www.raevalley.org http://www.nebraskamuseums.org/NEMuseumsNortheast.shtml Page 1 of 5 Nebraska Museums Association 7/7/11 6:17 PM Butte Community Historical Center & Museum 721 First St., Butte, Nebraska 68722 http://buttenebraska.com/TourismandRecreation.html Naper Historical Society PO Box 72 Naper, NE 68755 http://www.angelfire.com/ks/phxbrd/NHS.html Burt County Museum, E.C. Houston House * 319 North 13th St. Tekamah, NE 68061-0125 http://www.huntel.net/community/burtcomuseum/ Swedish Heritage Center 301 North Chard Ave. Oakland, NE 68045 http://www.ci.oakland.ne.us/interest.asp Decatur Historical Committee and Robert E. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-OO18 Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type aM entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic n.a. and/or common Main Street Historic District 2. Location 5 street & number___please see map and inventory forms not for publication city, town Fort Atkinson vicinity of state WI code 55 county Jefferson code 055 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) private unoccupied _ X_ commercial _X_park structure X both work in progress _ y- educational X private residence __ site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted X government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted _X_ industrial transportation X not applicable no military other: 4. Owner of Property name please see inventory forms street & number • n.a. city, town n.a. vicinity of state n.a, courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Jefferson County Courthouse street & number 320 S. Main Street city, town Jefferson state WI 53540, 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Wisconsin Inventory of title Historic Places nas tnis property been determined eligible? __ yes x no date 1975 federal X state __ county __ local depository for survey records State Historical Society of Wisconsin city, town Madison state WI 53706 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site _X_good ruins _JL_ altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Note: The current district has 60 buildings. -

Dr. Susan Laflesche Picotte: American Physician and Heroine Bernita L

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of Women in Educational Leadership Educational Administration, Department of 10-2005 Women in History--Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte: American Physician and Heroine Bernita L. Krumm Oklahoma State University - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Krumm, Bernita L., "Women in History--Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte: American Physician and Heroine" (2005). Journal of Women in Educational Leadership. 166. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel/166 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Educational Administration, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Women in Educational Leadership by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Women in History Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte: American Physician and Heroine Bernita L. Krumm Susan LaFlesche, youngest child in a family of one son and four daughters of Mary and Joseph LaFlesche, was born in 1865 on the Omaha reservation near Macy in northeastern Nebraska. LaFlesche was of mixed cultures, French and Native American. Her mother, Mary (One Woman), was a daughter of Dr. John Gale and Ni-co-mi of the Iowa tribe; Joseph, also known as Iron Eye (E-sta-mah-za), was a son of Joseph LaFlesche, a French trader and his wife, a woman of the Ponca tribe. Iron Eye was the last recognized chief of the Omaha and the last to become chief under the old Omaha rituals; he was the adopted son of Chief Big Elk, the First, of the Omahas. -

NEBRASKA STATE HISTORICAL MARKERS by COUNTY Nebraska State Historical Society 1500 R Street, Lincoln, NE 68508

NEBRASKA STATE HISTORICAL MARKERS BY COUNTY Nebraska State Historical Society 1500 R Street, Lincoln, NE 68508 Revised April 2005 This was created from the list on the Historical Society Website: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/markers/texts/index.htm County Marker Title Location number Adams Susan O. Hail Grave 3.5 miles west and 2 miles north of Kenesaw #250 Adams Crystal Lake Crystal Lake State Recreation Area, Ayr #379 Adams Naval Ammunition Depot Central Community College, 1.5 miles east of Hastings on U.S. 6 #366 Adams Kingston Cemetery U.S. 281, 2.5 miles northeast of Ayr #324 Adams The Oregon Trail U.S. 6/34, 9 miles west of Hastings #9 Antelope Ponca Trail of Tears - White Buffalo Girl U.S. 275, Neligh Cemetery #138 Antelope The Prairie States Forestry Project 1.5 miles north of Orchard #296 Antelope The Neligh Mills U.S. 275, Neligh Mills State Historic Site, Neligh #120 Boone St. Edward City park, adjacent to Nebr. 39 #398 Boone Logan Fontenelle Nebr. 14, Petersburg City Park #205 Box Butte The Sidney_Black Hills Trail Nebr. 2, 12 miles west of Hemingford. #161 Box Butte Burlington Locomotive 719 Northeast corner of 16th and Box Butte Ave., Alliance #268 Box Butte Hemingford Main Street, Hemingford #192 Box Butte Box Butte Country Jct. U.S. 385/Nebr. 87, ten miles east of Hemingford #146 Box Butte The Alliance Army Air Field Nebr. 2, Airport Road, Alliance #416 Boyd Lewis and Clark Camp Site: Sept 7, 1804 U.S. 281, 4.6 miles north of Spencer #346 Brown Lakeland Sod High School U.S. -

2014 Nebraska Attraction Attendance Counts City Name of Attraction

2014 Nebraska Attraction Attendance Counts % of Total Summer % of Summer Attendance from Attendance Attendance from Out of State (Memorial Day- Out of State City Name of Attraction Total Attendance Visitors Labor Day) Visitors Omaha Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium 1,700,378 34 774,320 38 Raymond Branched Oak State Recreation Area 1,476,467 Ashland Eugene T. Mahoney State Park 1,155,000 Louisville Platte River State Park 878,020 Fremont Fremont Lakes State Recreation Area 874,300 Lake McConaughy and Lake Ogallala State Recreation Ogallala Areas 821,269 Ponca Ponca State Park 783,707 Louisville Louisville Lakes State Recreation Area 572,000 Chadron Chadron State Park 480,300 Burwell Calamus Reservoir State Recreation Area 472,406 Venice Two Rivers State Recreation Area 436,065 Crawford Fort Robinson State Park 410,560 Lincoln Pawnee State Recreation Area 386,994 Omaha Omaha Children's Museum 290,996 30 104,537 42 Hickman Wagon Train State Recreation Area 259,208 North Platte Lake Maloney State Recreation Area 240,050 Lincoln Haymarket Park 227,600 Shubert Indian Cave State Park 224,450 Pierce Willow Creek State Recreation Area 220,350 Ralston Ralston Arena 215,778 13,633 Lincoln Lincoln Children's Zoo 204,000 11 104,000 12 Omaha The Durham Museum 189,654 22 60,735 28 Omaha Lauritzen Gardens and Kenefick Park 173,130 30 77,552 35 Omaha Joslyn Art Museum 163,324 17 39,307 27 Aurora Edgerton Explorit Center 160,578 15 36,835 20 Nebraska City Arbor Lodge State Historical Park and Arboretum 160,000 Minatare Lake Minatare State Recreation Area 155,312 Wahoo Lake Wanahoo State Recreation Area 143,608 Niobrara Niobrara State Park 130,980 Tekamah Summit Lake State Recreation Area 129,896 2014 Nebraska Attraction Attendance Counts Lexington Johnson Lake State Recreation Area 128,662 Ashland Lee G. -

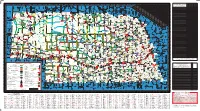

Nebraska Bicycle Map Legend 2 3 3 B 3 I N K C R 5 5 5 6 9 S55a 43 3 to Clarinda

Nebraska State Park Areas 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 Park entry permits required at all State Parks, TO HOT SPRINGS TO PIERRE TO MITCHELL TO MADISON 404 402 382 59 327 389 470 369 55 274 295 268 257 96 237 366 230 417 327 176 122 397 275 409 53 343 78 394 163 358 317 Recreation Areas and State Historical Parks. 100 MI. 83 68 MI. E 23 MI. 32 MI. NC 96 113 462 115 28 73 92 415 131 107 153 151 402 187 40 212 71 162 246 296 99 236 94 418 65 366 166 343 163 85 LIA Park permits are not available at every area. Purchase 18 TO PIERRE AL E 183 47 RIC 35 446 94 126 91 48 447 146 158 215 183 434 219 56 286 37 122 278 328 12 197 12 450 74 398 108 309 119 104 from vendor at local community before entering. 105 MI. D A K O T A T TYPE OF AREA CAMPING SANITARY FACILTIES SHOWERS ELEC. HOOKUPS DUMP STATION TRAILER PADS CABINS PICNIC SHELTERS RIDES TRAIL SWIMMING BOATING BOAT RAMPS FISHING HIKING TRAILS CONCESSION HANDICAP FACILITY 73 T S O U T H A 18 E E T H D A K O T A 18 F-6 B VU 413 69 139 123 24 447 133 159 210 176 435 220 69 282 68 89 279 328 26 164 43 450 87 398 73 276 83 117 S O U 18 471 103°00' 15' 98°30' LLE 1. -

Engineer Cantonment, Missouri Territory, 1819-1820: America's First Biodiversity Ineventory

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences Great Plains Studies, Center for 2008 Engineer Cantonment, Missouri Territory, 1819-1820: America's First Biodiversity Ineventory Hugh H. Genoways University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Brett C. Ratcliffe University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsresearch Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons, Plant Sciences Commons, and the Zoology Commons Genoways, Hugh H. and Ratcliffe, Brett C., "Engineer Cantonment, Missouri Territory, 1819-1820: America's First Biodiversity Ineventory" (2008). Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences. 927. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsresearch/927 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Great Plains Research 18 (Spring 2008):3-31 © 2008 Copyright by the Center for Great Plains Studies, University of Nebraska-Lincoln ENGINEER CANTONMENT, MISSOURI TERRITORY, 1819-1820: AMERICA'S FIRST BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY Hugh H. Genoways and Brett C. Ratcliffe Systematic Research Collections University o/Nebraska State Museum Lincoln, NE 68588-0514 [email protected] and [email protected] ABSTRACT-It is our thesis that members of the Stephen Long Expedition of 1819-20 completed the first biodiversity inventory undertaken in the United States at their winter quarters, Engineer Cantonment, Mis souri Territory, in the modern state of Nebraska. -

A NATIONAL MUSEUM of the Summer 2000 Celebrating Native

AmencanA NATIONAL MUSEUM of the Indiant ~ti • Summer 2000 Celebrating Native Traditions & Communities INDIAN JOURNALISM • THE JOHN WAYNE CLY STORY • COYOTE ON THE POWWOW TRAIL t 1 Smithsonian ^ National Museum of the American Indian DAVID S AIT Y JEWELRY 3s P I! t£ ' A A :% .p^i t* A LJ The largest and bestfôfltikfyi of Native American jewelry in the country, somçjmhem museum quality, featuring never-before-seen immrpieces of Hopi, Zuni and Navajo amsans. This collection has been featured in every major media including Vogue, Elle, Glamour, rr_ Harper’s Bazaar, Mirabella, •f Arnica, Mademoiselle, W V> Smithsonian Magazine, SHBSF - Th'NwYork N ± 1R6%V DIScbuNTDISCOUNT ^ WC ^ 450 Park Ave >XW\0 MEMBERS------------- AND television stations (bet. 56th/57th Sts) ' SUPPORTERS OF THE nationwide. 212.223.8125 NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE © CONTENTS Volume 1, Number 3, Summer 2000 10 Read\ tor Pa^JG One -MarkTrahantdescribeshowIndianjoumalistsHkeMattKelley, Kara Briggs, and Jodi Rave make a difference in today's newsrooms. Trahant says today's Native journalists build on the tradition of storytelling that began with Elias Boudinot, founder of the 19th century newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. 1 ^ WOVCn I hrOU^h Slone - Ben Winton describes how a man from Bolivia uses stone to connect with Seneca people in upstate New York. Stone has spiritual and utilitarian significance to indigeneous cultures across the Western Hemisphere. Roberto Ysais photographs Jose Montano and people from the Tonawanda Seneca Nation as they meet in upstate New York to build an apacheta, a Qulla cultural icon. 18 1 tie John Wayne Gly Story - John Wayne Cly's dream came true when he found his family after more than 40 years of separation. -

1984 Annual Report Nebraska Game and Parks Commission

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Publications 1984 1984 Annual Report Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebgamepubs "1984 Annual Report Nebraska Game and Parks Commission" (1984). Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Publications. 90. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebgamepubs/90 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. .' I I I , 1984 ANNUAL REPORT Nebraska Game and Parks Commission PURPOSE Husbandry of state's wildlife, park and outdoor recreation resources in the best long-term interest of the people. GOAL 1: To plan for and implement all policies and programs in an efficient and objective manner. GOAL 2: To maintain a rich and diverse environment in the lands and waters of Nebraska. GOAL 3: To provide outdoor recreation opportunities. GOAL 4: To manage wildlife resources for maximum benefit of the people. GOAL 5: To cultivate man's appreciation of this role in the world of nature. Eugene T. Mahoney was appointed to a six-year term as director of the Game and Parks Commission, effective July 22, 1976. He was appointed to his second term which began April 22, 1982. TABLE OF CONTENTS Administration 1 Budget & Fiscal . 4 Engineering ................................................ 13 Fisheries Division ........................................ 20 Information & Education ................................... 25 Law Enforcement .....................• ..•..................... 27 Operations and Construction .............••................ -

Pioneer Reminiscences

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Pioneer Reminiscences Full Citation: Pioneer Reminiscences, Transactions and Reports of the Nebraska State Historical Society 1 (1885): 25- 85. [Transactions and Reports, Equivalent to Series 1-Volume 1] URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1885Pio_Rem.pdf Date: 12/19/2012 Article Summary: Pioneer Reminiscences: Historical recollections in and about Otoe county; Historical letters of Father DeSmet; First white child born in Nebraska; Father William Hamilton on traditional origin of Omahas and other tribes; Robert W Furnas on the same; Some historical data about Washington county; Relics in possession of the Society; First female suffragist movement in Nebraska; Autobiography of Rev William Hamilton; Father Hamilton on derivation of Indian names; Henry Fontenelle on derivation of Indian names; History of Omaha Indians; Anecdotes relating to "White Cow" or "White Buffalo" Cataloging Information: Names: James Fitche, John Boulware, S B Davis, S F Nuckolls, E H Cowles, Father De Smet, Rosa Harnois Knight, William Hamilton, Robert W Furnas, W H Woods, Mrs Amelia Bloomer, Rev William Hamilton, H Fontanelle Place Names: Otoe County , Nebraska; Washington County, Nebraska; Burt County, Nebraska Keywords: Steamboat Swatara, Relics, suffragist movement, Indian languages; Omaha Indians HISTORICAL RECOLLECTIONS IN AND ABOUT OTOE COUNTY. -

Fort Atkinson, Nebraska � Film RG502 Fort Atkinson, Nebraska

Fort Atkinson, Nebraska � film RG502 Fort Atkinson, Nebraska Records: 1819-1957 Cubic ft.: 1.5 Approx. # of Items: 4 boxes of c.100 items and 10 reels of microfilm HISTORICAL NOTE Fort Atkinson, Nebraska, on the Council Bluffs, was the most remote U.S. military post on the western frontier from 1819-1827. In 1819, John C. Calhoun, Secretary of War, dispatched the Yellow-stone Expeditionary force under Col. Henry Atkinson as part of a plan to construct a chain of fortifications west of the Mississippi River. These forts were to serve as a warning to the British trading companies and to protect the fur trade along the Upper Missouri. The expedition had reached the Council Bluffs, when winter forced them to construct a camp. This camp was named Cantonment Missouri. In 1820, Congress abandoned the plan for the series of forts, leaving only the new post at the Council Bluffs. When floods destroyed this camp in the spring of 1820, a new site was selected on top of the Bluffs. The newly constructed post was known simply as Council Bluffs until 1821 when it was officially designated Fort Atkinson. Fort Atkinson was garrisoned by the Rifle Regiment and the Sixth Infantry Regiment. In 1821, as part of a military cutback, the two regiments were combined and some of the troops were discharged. The troops at the fort saw almost no military operations with the exception of the brief Arickara War of 1823 after a party of fur traders were attached by Indians. Fort Atkinson was to survive as an active military post only until 1827 when it was abandoned.