Crossing Cultural Borders – a Journey Towards Understanding and Celebration in Aboriginal Australian and Non-Aboriginal Australian Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

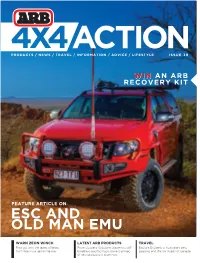

ESC and Old Man Emu

AI CT ON PRODUCTS / NEWS / TRAVEL / INFORMATION / ADVICE / LIFESTYLE ISS9 UE 3 W IN AN ARB RECOVERY KIT FEATURE ARTICLE ON ESC AND OLD MAN EMU WARN ZEON WINCH LATEST ARB PRODUCTS TRAVEL Find out why the latest offering From Outback Solutions drawers to diff Explore El Questro, Australia’s best from Warn is a game changer breathers and flip flops, there is a heap beaches and the Ice Roads of Canada of new products in store now CONTENTS PRODUCTS COMPETITIONS & PROMOTIONS 4 ARB Intensity LED Driving Light Covers 5 Win An ARB Back Pack 16 Old Man Emu & ESC Compatibility 12 ARB Roof Rack With Free 23 ARB Differential Breather Kit Awning Promotion 26 ARB Deluxe Bull Bar for Jeep WK2 24 Win an ARB Recovery Kit Grand Cherokee 83 On The Track Photo Competition 27 ARB Full Extension Fridge Slide 32 Warn Zeon Winch 44 Redarc In-Vehicle Chargers 45 ARB Cab Roof Racks For Isuzu D-Max REGULARS & Holden Colorado 52 Outback Solutions Drawers 14 Driving Tips & Techniques 54 Latest Hayman Reese Products 21 Subscribe To ARB 60 Tyrepliers 46 ARB Kids 61 Bushranger Max Air III Compressor 50 Behind The Shot 66 Latest Thule Accessories 62 Photography How To 74 Hema HN7 Navigator 82 ARB 24V Twin Motor Portable Compressor ARB 4X4 ACTION Is AlsO AvAIlABlE As A TRAVEL & EVENTS FREE APP ON YOUR IPAD OR ANDROID TABLET. 6 Life’s A Beach, QLD BACk IssuEs CAN AlsO BE 25 Rough Stuff, Australia dOwNlOAdEd fOR fREE. 28 Ice Road, Canada 38 Water For Africa, Tanzania 56 The Eastern Kimberley, WA Editor: Kelly Teitzel 68 Emigrant Trail, USA Contributors: Andrew Bellamy, Sam Boden, Pat Callinan, Cassandra Carbone, Chris Collard, Ken Duncan, Michael Ellem, Steve Fraser, Matt 76 ARB Eldee Easter 4WD Event, NSW Frost, Rebecca Goulding, Ron Moon, Viv Moon, Mark de Prinse, Carlisle 78 Gunbarrel Hwy, WA Rogers, Steve Sampson, Luke Watson, Jessica Vigar. -

Download the .Pdf

PREPARING FOR THE THIRD AGE OF LIFE The following information is offered for the general consideration and use of archdioceses and dioceses interested in enhancing the information provided to their priests as they contemplate and prepare for retirement. Each section of this Manual must be carefully reviewed and then, as needed, altered to reflect the policies and procedures that guide each archdioceses’ or dioceses’ pension plan and related retirement benefit programs available to qualifying priests. Prior to releasing or using a Manual intended to reflect an archdioceses’ or dioceses’ own pension plan and related retirement benefit programs, it is strongly recommended that the advice and guidance of a qualified financial and retirement benefits advisor familiar with the U.S. Catholic Church be sought. I. INTRODUCTION "Grow old along with me! The best is yet to be, the last of life, for which the first was made..." (Robert Browning) Ready or not, sometime after the age of 70, most workers leave the job they planned for and pursued for a great portion of their lives. Although retirement is viewed by each person as an individual experience, it is actually a part of living in which all persons, in some way, share common problems and pleasures. This pre-retirement manual has been prepared to help priests of the Diocese of ____________ plan and get ready for the "third age" years so they can live them in a fulfilling and joyous way. LSRP ● P.O. Box 1019, Bonita Springs, FL 34133 ● www.LSRPinc.org 1 | P a g e Every priest is st r o ng l y encouraged to make appropriate long-range plans for when he resigns from the ecclesiastical office, commonly referred to as "retirement." These plans should include at what age he prefers to offer his resignation, where he wishes to reside, how he wishes to continue to exercise his priestly ministry, and other practical matters (e.g., health, finances, etc.). -

Let's Face It, the 1980'S Were Responsible for Some Truly Horrific

80sX Let’s face it, the 1980’s were responsible for some truly horrific crimes against fashion: shoulder-pads, leg-warmers, the unforgivable mullet ! What’s evident though, now more than ever, is that the 80’s provided us with some of the best music ever made. It doesn’t seem to matter if you were alive in the 80’s or not, those songs still resonate with people and trigger a joyous reaction for anyone that hears them. Auckland band 80sX take the greatest new wave, new romantic and synth pop hits and recreate the magic and sounds of the 80’s with brilliant musicianship and high energy vocals. Drummer and programmer Andrew Maclaren is the founding member of multi platinum selling band stellar* co-writing mega hits 'Violent', 'All It Takes' and 'Taken' amongst others. During those years he teamed up with Tom Bailey from iconic 80’s band The Thompson Twins to produce three albums, winning 11 x NZ music awards, selling over 100,000 albums and touring the world. Andrew Thorne plays lead guitar and brings a wealth of experience to 80’sX having played all the guitars on Bic Runga’s 11 x platinum debut album ‘Drive’. He has toured the world with many of New Zealand’s leading singer songwriter’s including Bic, Dave Dobbyn, Jan Hellriegel, Tim Finn and played support for international acts including Radiohead, Bryan Adams and Jeff Buckley. Bass player Brett Wells is a Chartered Director and Executive Management Professional with over 25 years operations experience in Webb Group (incorporating the Rockshop; KBB Music; wholesale; service and logistics) and foundation member of the Board. -

Mick Evans Song List 1

MICK EVANS SONG LIST 1. 1927 If I could 2. 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Here Without You 3. 4 Non Blondes What’s Going On 4. Abba Dancing Queen 5. AC/DC Shook Me All Night Long Highway to Hell 6. Adel Find Another You 7. Allan Jackson Little Bitty Remember When 8. America Horse with No Name Sister Golden Hair 9. Australian Crawl Boys Light Up Reckless Oh No Not You Again 10. Angels She Keeps No Secrets from You MICK EVANS SONG LIST Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again 11. Avicii Hey Brother 12. Barenaked Ladies It’s All Been Done 13. Beatles Saw Her Standing There Hey Jude 14. Ben Harper Steam My Kisses 15. Bernard Fanning Song Bird 16. Billy Idol Rebel Yell 17. Billy Joel Piano Man 18. Blink 182 Small Things 19. Bob Dylan How Does It Feel 20. Bon Jovi Living on a Prayer Wanted Dead or Alive Always Bead of Roses Blaze of Glory Saturday Night MICK EVANS SONG LIST 21. Bruce Springsteen Dancing in the dark I’m on Fire My Home town The River Streets of Philadelphia 22. Bryan Adams Summer of 69 Heaven Run to You Cuts Like A Knife When You’re Gone 23. Bush Glycerine 24. Carly Simon Your So Vein 25. Cheap Trick The Flame 26. Choir Boys Run to Paradise 27. Cold Chisel Bow River Khe Sanh When the War is Over My Baby Flame Trees MICK EVANS SONG LIST 28. Cold Play Yellow 29. Collective Soul The World I know 30. Concrete Blonde Joey 31. -

An Ethnography of Health Promotion with Indigenous Australians in South East Queensland

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292140373 "We don't tell people what to do": An ethnography of health promotion with Indigenous Australians in South East Queensland Thesis · December 2015 CITATIONS READS 0 36 1 author: Karen McPhail-Bell University of Sydney 25 PUBLICATIONS 14 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Karen McPhail-Bell Retrieved on: 25 October 2016 “We don’t tell people what to do” An ethnography of health promotion with Indigenous Australians in South East Queensland Karen McPhail-Bell Bachelor of Behavioural Science, Honours (Public Health) Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Public Health and Social Work Queensland University of Technology 2015 Key words Aboriginal, Aboriginal Medical Service, Australia, colonisation, community controlled health service, critical race theory, cultural interface, culture, ethnography, Facebook, government, health promotion, identity, Indigenous, Instagram, mainstream, policy, postcolonial theory, public health, relationship, self- determination, social media, Torres Strait Islander, Twitter, urban, YouTube. ii Abstract Australia is a world-leader in health promotion, consistently ranking in the best performing group of countries for healthy life expectancy and health expenditure per person. However, these successes have largely failed to translate into Indigenous health outcomes. Given the continued dominance of a colonial imagination, little research exists that values Indigenous perspectives, knowledges and practice in health promotion. This thesis contributes to addressing this knowledge gap. An ethnographic study of health promotion practice was undertaken within an Indigenous-led health promotion team, to learn how practitioners negotiated tensions of daily practice. -

1 Picturing a Golden Age: September and Australian Rules Pauline Marsh, University of Tasmania It Is 1968, Rural Western Austra

1 Picturing a Golden Age: September and Australian Rules Pauline Marsh, University of Tasmania Abstract: In two Australian coming-of-age feature films, Australian Rules and September, the central young characters hold idyllic notions about friendship and equality that prove to be the keys to transformative on- screen behaviours. Intimate intersubjectivity, deployed in the close relationships between the indigenous and nonindigenous protagonists, generates multiple questions about the value of normalised adult interculturalism. I suggest that the most pointed significance of these films lies in the compromises that the young adults make. As they reach the inevitable moral crisis that awaits them on the cusp of adulthood, despite pressures to abandon their childhood friendships they instead sustain their utopian (golden) visions of the future. It is 1968, rural Western Australia. As we glide along an undulating bitumen road up ahead we see, from a low camera angle, a school bus moving smoothly along the same route. Periodically a smattering of roadside trees filters the sunlight, but for the most part open fields of wheat flank the roadsides and stretch out to the horizon, presenting a grand and golden vista. As we reach the bus, music that has hitherto been a quiet accompaniment swells and in the next moment we are inside the vehicle with a fair-haired teenager. The handsome lad, dressed in a yellow school uniform, is drawing a picture of a boxer in a sketchpad. Another cut takes us back outside again, to an equally magnificent view from the front of the bus. This mesmerising piece of cinema—the opening of September (Peter Carstairs, 2007)— affords a viewer an experience of tranquillity and promise, and is homage to the notion of a golden age of youth. -

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why Is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving?

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving? A Thesis Submitted By Jacob Zvi for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Health, Arts & Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne © Jacob Zvi 2019 Swinburne University of Technology All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. II Abstract In 2004, annual Australian viewership of Australian cinema, regularly averaging below 5%, reached an all-time low of 1.3%. Considering Australia ranks among the top nations in both screens and cinema attendance per capita, and that Australians’ biggest cultural consumption is screen products and multi-media equipment, suggests that Australians love cinema, but refrain from watching their own. Why? During its golden period, 1970-1988, Australian cinema was operating under combined private and government investment, and responsible for critical and commercial successes. However, over the past thirty years, 1988-2018, due to the detrimental role of government film agencies played in binding Australian cinema to government funding, Australian films are perceived as under-developed, low budget, and depressing. Out of hundreds of films produced, and investment of billions of dollars, only a dozen managed to recoup their budget. The thesis demonstrates how ‘Australian national cinema’ discourse helped funding bodies consolidate their power. Australian filmmaking is defined by three ongoing and unresolved frictions: one external and two internal. Friction I debates Australian cinema vs. Australian audience, rejecting Australian cinema’s output, resulting in Frictions II and III, which respectively debate two industry questions: what content is produced? arthouse vs. -

'Noble Savages' on the Television

‘Nobles and savages’ on the television Frances Peters-Little The sweet voice of nature is no longer an infallible guide for us, nor is the independence we have received from her a desirable state. Peace and innocence escaped us forever, even before we tasted their delights. Beyond the range of thought and feeling of the brutish men of the earli- est times, and no longer within the grasp of the ‘enlightened’ men of later periods, the happy life of the Golden Age could never really have existed for the human race. When men could have enjoyed it they were unaware of it and when they have understood it they had already lost it. JJ Rousseau 17621 Although Rousseau laments the loss of peace and innocence; little did he realise his desire for the noble savage would endure beyond his time and into the next millennium. How- ever, all is not lost for the modern person who shares his bellow, for a new noble and savage Aborigine resonates across the electronic waves on millions of television sets throughout the globe.2 Introduction Despite the numbers of Aboriginal people drawn into the Australian film and television industries in recent years, cinema and television continue to portray and communicate images that reflect Rousseau’s desires for the noble savage. Such desires persist not only in images screened in the cinema and on television, but also in the way that they are dis- cussed. The task of ridding non-fiction film and television making of the desire for the noble and the savage is an essential one that must be consciously dealt with by both non- Aboriginal and Aboriginal film and television makers and their critics. -

© 2017 Star Party Karaoke 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed 45 Shinedown 98.6 Keith 247 Artful Dodger Feat

Numbers Song Title © 2017 Star Party Karaoke 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed 45 Shinedown 98.6 Keith 247 Artful Dodger Feat. Melanie Blatt 409 Beach Boys, The 911 Wyclef Jean & Mary J Blige 1969 Keith Stegall 1979 Smashing Pumpkins, The 1982 Randy Travis 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 1999 Wilkinsons, The 5678 Step #1 Crush Garbage 1, 2 Step Ciara Feat. Missy Elliott 1, 2, 3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys, The 100 Years Five For Fighting 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis & The News 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 18 & Life Skid Row 18 Till I Die Bryan Adams 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin 19-2000 Gorillaz 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc 20th Century Fox Doors, The 21 Questions 50 Cent Feat Nate Dogg 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band, The 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 25 Miles Edwin Starr 25 Minutes Michael Learns To Rock 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 29 Nights Danni Leigh 29 Palms Robert Plant 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 30 Days In The Hole Humble Pie 30,000 Pounds Of Bananas Harry Chapin 32 Flavours Alana Davis 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 4 Seasons Of Loneiness Boyz 2 Men 4 To 1 In Atlanta Tracy Byrd 4+20 Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young 42nd Street Broadway Show “42nd Street” 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 4th Of July Shooter Jennings 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 50,000 Names George Jones 50/50 Lemar 500 Miles (Away From Home) Bobby Bare -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Festival Programm October 04-12, 2012 Cinemas Berlin-Kreuzberg Eiszeit & Moviemento

FESTIVAL PROGRAMM OCTOBER 04-12, 2012 CINEMAS BERLIN-KREUZBERG EISZEIT & MOVIEMENTO 2 1 FESTIVAL PROGRAMM - KINO EISZEIT Opening Films THURSDAY 4.10.2012 17:15 Hiroshima, A Mother's Prayer Director: Motoo Ogasawara Japan, 1990, 30 min, Language German Film of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum A documentary film featuring footage captured immediately after the blast, it calls for the abolition of nuclear weapons and world peace from the viewpoint of a mother in Hiroshima. The Secret and the Sacred. Two Worlds at Los Alamos (Los Alamos. Und die Erben der Bombe) Germany, 2003, 45 min, Language German Director: Claus Biegert, Production: Denkmal-Film / Hessischer Rundfunk / arte Hidden in the mountains of Northern New Mexico lies the birthplace of the Atomic Age: Los Alamos, home of the "Manhattan Project". Here Robert J. Oppenheimer and his staff created the first atomic bomb, "Trinity", the scientific prototype to "Little Boy" and "Fat Man," the bombs which hastened the end of World War II by leveling Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Although the laboratory is today also a leading center of genetic research, it remains a place of secrecy, for its main mission is to maintain the existing nuclear arsenal - a task that hides behind the name, "Stockpile Stewardship". The secret meets the sacred upon the mesa of Los Alamos. The lab takes up forty- three square miles - indigenous land of the Tewa people from the pueblos Santa Clara and San Ildefonso. The local Indians are cut off from their traditional shrines of worship: their prayer sites are either fenced off or contaminated. One of the sacred places contains the petroglyph of Avanyu, the mythic serpent that is the guardian of the springs. -

Katie Noonan, 2019 Extended

Katie Noonan, 2019 Extended bio: Over the past 20 years, five-time ARIA award-winning artist Katie Noonan has proven herself one of Australia’s most hardworking, versatile and prolific artists. Named one of the greatest Australian singers of all time by the Herald Sun, Katie has produced 20 albums throughout her career, with seven times platinum record sales under her belt and 25 ARIA award nominations that span diverse genres. Katie first came into the nation’s view in 2002 while fronting indie rock band george – their debut album, the two-times platinum Polyserena, rolled in at number one in the ARIA charts. They ultimately won the ARIA award for Breakthrough Artist that same year. Since then, Katie has performed by invitation for members of the Danish and British Royal families, and His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama. She was an inaugural recipient of the prestigious Sidney Myer Creative Fellowship in 2011, an honour awarded to candidates that display outstanding talent and exceptional courage. In 2018, Katie took on the Commonwealth Games Opening and Closing ceremonies as Music Director, performing to more than a billion viewers worldwide. Katie is a rare songwriter; equally at home leading a symphony orchestra as she is performing in a small jazz club, she has the ability to flourish in any genre – whether that’s in gentle folk storytelling or in the grandiosity of an operatic performance. Katie has also collaborated with Australian electronic producers Flight Facilities on their acclaimed 2014 record Down To Earth, and in 2016 she joined Perth hip-hop artist Drapht on his track Raindrops.