The Semiotic Stance*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peirce's Theory of Communication and Its Contemporary Relevance

Ahti-Veikko Pietarinen Peirce’s Theory of Communication and Its Contemporary Relevance Introduction The mobile era of electronic communication has created a huge semi- otic system, constructed out of triadic components envisaged by the American scientist and philosopher Charles S. Peirce (1839–1914), such as icons, indices and symbols, and signs, objects and interpretants. Iconic signs bear a physical resemblance to what they represent. Indices point at something and say “there!”, and symbols signify objects by conven- tions of a community.1 All signs give rise to interpretants in the minds of the interpreters. It is nonetheless regrettable that the somewhat simplistic triadic ex- posé of Peirce’s theory of signs has persisted in semiotics as the some- how exhaustive and final description of what Peirce intended. The more fascinating and richer structure of signs emerging from their intimate relation to intercommunication and interaction (Peirce’s terms) has been noted much less frequently. Despite this shortcoming, the full Peircean road to inquiry – per- formed by the dynamic community of learning inquirers, or the com- 1 In fact, according to Peirce (2.278 [1895]): “The only way of directly communi- cating an idea is by means of an icon; and every indirect method of communicating an idea must depend for its establishment upon the use of an icon.” Peirce’s chef d’œuvre came shortly after these remarks into being as his diagrammatic system of existential graphs, a thoroughly iconic representation of and a way of reasoning about “moving pictures of thought”, which encompassed not only propositional and predicate logic, but also modalities, higher-order notions, abstraction and category-theoretic notions. -

Download/ Nwp File/2013/Notes on a Working Hypothesis.Pdf?X-R=Pcfile D

Psychosemiotics: communication as psychological action Marko Mili Doctor of Philosophy (Psychology) University of Western Sydney November 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my wife Juliana Payne for her patience, accessibility for debate on all issues, practical assistance, and help in avoiding clichés like the plague. My parents Petar and Nediljka Mili shared their enthusiasm for learning and balanced their encouragement with flexibility about the direction that their influence took. My sister, Angela Mili, provided moral and practical support. To my extended family—Ante, Maria, Mirko, Lina, Kristina, Anthony, and Nikolas Mili; and Steve and Veronica Harwood—thank you for your support for this project. Thanks to Megan McDonald for helpful grammatical-stylistic suggestions and to Domagoj Veli, who has been an enthusiastic supporter of this project from the beginning. Professor Philip Bell, Professor Theo van Leeuwen, Dr Scott Mann and Dr Phillip Staines provided me with valuable opportunities to assist in teaching their courses in mass media, semiotics, social theory and the philosophy of language. This experience has significantly enhanced the present work. My supervisor, Dr Agnes Petocz, consistently provided detailed and incisive feedback throughout the conception and execution of this work. Her vision of a richer science of psychology has been inspirational for me. As co-supervisor, Professor Philip Bell has been an exemplary mentor and model for post- disciplinary research. ii STATEMENT OF AUTHENTICATION The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in whole or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. -

Picasso's Cubism: Politics And/Or Semiosis

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D+CI) Spring 2012 Professor Caroline A. Jones Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section. Department of Architecture Lecture 10 SERIALISM & SEMIOSIS: Lecture 10: Picasso's Cubism: Politics and/or Semiosis 1990: Picasso's primitivism is part of a cultural discourse in which "Africa" conveyed widely accepted meanings that cannot be extricated from allusions to its art and people. - Patricia Leighton, 'The White Peril and I 'art m?gre ... " 1981 /'98: The extraordinary contribution of collage is that it is the first instance within the pictorial arts of anything like a systematic exploration of the conditions of representability entailed by the sign. - Rosalind Krauss, "In the Name of Picasso" I. Picasso's escape via Paris: from paternal academy, and provincialism A. The international "Youth Style" (Jugendstil, Joven Tut, Arte Joven magazines) B. Impressionist modes and motives, Barcelona -> Paris C. "Blue period" 1) the depressed fliineur (harlequin) 2) a "Moorish" Spaniard in France II. Picasso's escape from Paris: The Demoiselles d' A vignon A. Picasso's self-described "exorcism" - of what? B. The way modem abstraction works 1) African sculpture as "raisonnable ,. (conceptual) 2) towards a system of visual signs (away from representing towards signifying) C. Colonialist critique through performing the primitive (how different from Gauguin?) III. Cubism- hermetic language, or popular culture? A. "Braque, c 'est ma femme" - the codes of a private language 1) Georges Braque - wit, conceptualism, pattern, (French) fancypaint traditions 2) Pablo Picasso - weight, sculptural concerns, "modeling," oscillations between depth! surface B. The force of caricature in the portraits C. -

The Category of Code Is Widely Used Not Only in Semiotics, but Also In

Nadezda N. Izotova The category of code is widely used not only in PhD in Cultural Studies, Associate Professor of the semiotics, but also in other humanitarian disciplines Department of the Japanese, Korean, Indonesian and Mongolian languages, Moscow State Institute of and is significantly promising. French philosopher and International Relations (MGIMO) of the Ministry of cultural theorist Michel Foucault notes that the Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. 119454, 76 Vernadskogo av., Moscow, Russian Federation. fundamental codes of any culture play a key role in a ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2817-004X. person’s life and determine “the empirical orders with E-mail: [email protected]. which he will be dealing and within which he will be at Received in: Approved in: home” (FOUCAULT, 1977, p. 37). Despite different 2021-01-10 2021-02-02 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24115/S2446-6220202172681p.33-41 approaches to the classification and interpretation of the ontological status and to the culture code functioning, scholars agree that the culture code is a part of the cultural process, its semantic core, rather than a description of a cultural phenomenon per se. The relevance of understanding and interpreting culture codes is determined by the necessity of arranging, classifying, and analyzing the code systems. The decryption of the culture codes and the reconstruction of the corresponding historical and cultural contexts are vital tasks not only for culturology, but also for other humanities. The study of culture codes is regarded as one of the basic means for understanding the mentality and value orientations of both any particular individual and the “cosmo-psycho-logos” of any ethnic group (GACHEV, 1995). -

Marketing Semiotics

Marketing Semiotics Professor Christian Pinson Semiosis, i.e. the process by which things and events come to be recognized as signs, is of particular relevance to marketing scholars and practitioners. The term marketing encompasses those activities involved in identifying the needs and wants of target markets and delivering the desired satisfactions more effectively and efficiently than competitors. Whereas early definitions of marketing focused on the performance of business activities that direct the flow of goods and services from producer to consumer or user, modern definitions stress that marketing activities involve interaction between seller and buyer and not a one- way flow from producer to consumer. As a consequence, the majority of marketers now view marketing in terms of exchange relationships. These relationships entail physical, financial, psychological and social meanings. The broad objective of the semiotics of marketing is to make explicit the conditions under which these meanings are produced and apprehended. Although semioticians have been actively working in the field of marketing since the 1960s, it is only recently that semiotic concepts and approaches have received international attention and recognition (for an overview, see Larsen et al. 1991, Mick, 1986, 1997 Umiker- Sebeok, 1988, Pinson, 1988). Diffusion of semiotic research in marketing has been made difficult by cultural and linguistic barriers as well as by divergence of thought. Whereas Anglo-Saxon researchers base their conceptual framework on Charles Pierce's ideas, Continental scholars tend to refer to the sign theory in Ferdinand de Saussure and to its interpretation by Hjelmslev. 1. The symbolic nature of consumption. Consumer researchers and critics of marketing have long recognized the symbolic nature of consumption and the importance of studying the meanings attached by consumers to the various linguistic and non-linguistic signs available to them in the marketplace. -

A Semiotic Theory of Music: According to a Peircean Rationale

A SEMIOTIC THEORY OF MUSIC: ACCORDING TO A PEIRCEAN RATIONALE The Sixth International Conference on Musical Signification University of Helsinki Université de Provence (Aix-Marselle I) Aix-en-Provence, December 1-5, 1998 José Luiz Martinez (Ph.D.) [1] The recent growth of musical applications of Peirce’s general theory of signs, such as in the works of David Lidov (1986), Robert Hatten (1994), William Dougherty (1993, 1994), shows that this approach, once set properly in both musical and semiotic contexts, has great analytical power on questions of musical signification. In this paper I will present the structure of a semiotic theory of music, as demonstrated in my doctoral dissertation, Semiosis in Hindustani Music (Imatra: International Semiotics Institute), submitted and approved by the University of Helsinki in 1997. [2] Peirce, in his studies of semiotics, concluded that thought is only possible by means of signs (vide CP 1.538, 4.551, 5.253). Music is a species of thought; and thus, the idea that music is sign and depends on significative processes, or semiosis, is obviously true. A musical sign can be a system, a composition or its performance, a musical form, a style, a composer, a musician, hers or his instrument, and so on. According to Peirce, signification occurs in a triadic relation of a sign and the object it stands for to an interpretant (CP 6.347), which - in music - is another sign developed in the mind of a listener, musician, composer, analyst or critic. [3] In Peirce’s classification of the sciences, semiotics (or semeiotic) has three branches: Speculative Grammar, Critic and Methodeutic (or Speculative Rhetoric) (CP 1.192). -

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA Qualia (singular, quale) are cultural emergents that manifest phenomenally as sensuous features or qualities. The anthropological challenge presented by qualia is to theorize elements of experience that are semiotically generated but apperceived as non-signs. Qualia are not reducible to a psychology of individual perceptions of sensory data, to a cultural ontology of “materiality,” or to philosophical intuitions about the subjective properties of consciousness. The analytical solution to the challenge of qualia is to con- sider tone in relation to the familiar linguistic anthropological categories of token and type. This solution has been made methodologically practical by conceptualizing qualia, in Peircean terms, as “facts of firstness” or firstness “under its form of secondness.” Inthephilosophyofmind,theterm“qualia”hasbeenusedtodescribetheineffable, intrinsic, private, and directly or immediately apprehensible experiences of “the way things seem,” which have been taken to constitute the atomic subjective properties of consciousness. This concept was challenged in an influential paper by Daniel Dennett, who argued that qualia “is a philosophers’ term which fosters nothing but confusion, and refers in the end to no properties or features at all” (Dennett 1988, 387). Dennett concluded, correctly, that these diverse elements of feeling, made sensuously present atvariouslevelsofattention,wereactuallyidiosyncraticresponsestoapperceptions of “public, relational” qualities. Qualia were, in effect, -

Discourse Types in Stand-Up Comedy Performances: an Example of Nigerian Stand-Up Comedy

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2015.3.1.filani European Journal of Humour Research 3 (1) 41–60 www.europeanjournalofhumour.org Discourse types in stand-up comedy performances: an example of Nigerian stand-up comedy Ibukun Filani PhD student, Department of English, University of Ibadan [email protected] Abstract The primary focus of this paper is to apply Discourse Type theory to stand-up comedy. To achieve this, the study postulates two contexts in stand-up joking stories: context of the joke and context in the joke. The context of the joke, which is inflexible, embodies the collective beliefs of stand-up comedians and their audience, while the context in the joke, which is dynamic, is manifested by joking stories and it is made up of the joke utterance, participants in the joke and activity/situation in the joke. In any routine, the context of the joke interacts with the context in the joke and vice versa. For analytical purpose, the study derives data from the routines of male and female Nigerian stand-up comedians. The analysis reveals that stand-up comedians perform discourse types, which are specific communicative acts in the context of the joke, such as greeting/salutation, reporting and informing, which bifurcates into self- praising and self denigrating. Keywords: discourse types; stand-up comedy; contexts; jokes. 1. Introduction Humour and laughter have been described as cultural universal (Oring 2003). According to Schwarz (2010), humour represents a central aspect of everyday conversations and all humans participate in humorous speech and behaviour. This is why humour, together with its attendant effect- laughter, has been investigated in the field of linguistics and other disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, sociology and anthropology. -

Title Peirce's General Theory of Signs Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Title Peirce's General Theory of Signs Author(s) Clare Thornbury Finding Meaning, Cultures Across Borders: International Citation Dialogue between Philosophy and Psychology (2011): 49-57 Issue Date 2011-03-31 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/143046 The copyright of papers included in this paper belongs to each Right author. Type Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University 49 Peirce's General Theory of Signs CLARE THORNBURY Institute of Education, University of London Charles. S Peirce was one ofthe founders ofPragmatism, alongside William James and John Dewey. This paper looks at Peirce's later work on his theory of signs, or semiotic. Peirce's semiotic is a broad one, including as signs things that other semioticians may reject. Peirce's semiotic includes a key division ofsigns into the three categories ofIcon, Index and Symbol. This trichotomy and the breadth ofPeirce's semiotic makes it well suited to, for example, a semiology of cinema. The basic structure ofthe sign in Peirce is also triadic, being a relation between sign-object-interpretant, and this brings us to a further appreciation of the sign as sign-action: a move from semiotic to semiosis. Peirce's approach to the philosophy of language goes beyond language to a theory of signs in general, and this 'semiotic' is deeply embedded within his broader systematic philosophical works. To understand it therefore, it is helpful to do two things: 1) to understand the breadth of Peirce's semiotic and 2) to differentiate it from other philosophical theories in the field. -

Redalyc.Intersemiotic Translation from Rural/Biological to Urban

Razón y Palabra ISSN: 1605-4806 [email protected] Universidad de los Hemisferios Ecuador Sánchez Guevara, Graciela; Cortés Zorrilla, José Intersemiotic Translation from Rural/Biological to Urban/Sociocultural/Artistic; The Case of Maguey and Other Cacti as Public/Urban Decorative Plants.” Razón y Palabra, núm. 86, abril-junio, 2014 Universidad de los Hemisferios Quito, Ecuador Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=199530728032 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative RAZÓN Y PALABRA Primera Revista Electrónica en Iberoamerica Especializada en Comunicación. www.razonypalabra.org.mx Intersemiotic Translation from Rural/Biological to Urban/Sociocultural/Artistic; The Case of Maguey and Other Cacti as Public/Urban Decorative Plants.” Graciela Sánchez Guevara/ José Cortés Zorrilla.1 Abstract. This paper proposes, from a semiotic perspective on cognition and working towards a cognitive perspective on semiosis, an analysis of the inter-semiotic translation processes (Torop, 2002) surrounding the maguey and other cacti, ancestral plants that now decorate public spaces in Mexico City. The analysis involves three semiotics, Peircean semiotics, bio-semiotics, and cultural semiotics, and draws from other disciplines, such as Biology, Anthropology, and Sociology, in order to construct a dialogue on a trans- disciplinary continuum. The maguey and other cactus plants are resources that have a variety of uses in different spaces. In rural spaces, they are used for their fibers (as thread in gunny sacks, floor mats, and such), for their leaves (as roof tiles, as support beams, and in fences), for their spines (as nails and sewing needles), and their juice is drunk fresh (known as aguamiel or neutli), fermented (a ritual beverage known as pulque or octli), or distilled (to produce mescal, tequila, or bacanora). -

Media Theory and Semiotics: Key Terms and Concepts Binary

Media Theory and Semiotics: Key Terms and Concepts Binary structures and semiotic square of oppositions Many systems of meaning are based on binary structures (masculine/ feminine; black/white; natural/artificial), two contrary conceptual categories that also entail or presuppose each other. Semiotic interpretation involves exposing the culturally arbitrary nature of this binary opposition and describing the deeper consequences of this structure throughout a culture. On the semiotic square and logical square of oppositions. Code A code is a learned rule for linking signs to their meanings. The term is used in various ways in media studies and semiotics. In communication studies, a message is often described as being "encoded" from the sender and then "decoded" by the receiver. The encoding process works on multiple levels. For semiotics, a code is the framework, a learned a shared conceptual connection at work in all uses of signs (language, visual). An easy example is seeing the kinds and levels of language use in anyone's language group. "English" is a convenient fiction for all the kinds of actual versions of the language. We have formal, edited, written English (which no one speaks), colloquial, everyday, regional English (regions in the US, UK, and around the world); social contexts for styles and specialized vocabularies (work, office, sports, home); ethnic group usage hybrids, and various kinds of slang (in-group, class-based, group-based, etc.). Moving among all these is called "code-switching." We know what they mean if we belong to the learned, rule-governed, shared-code group using one of these kinds and styles of language. -

Language in Society: an Introduction to Linguistic & Semiotic Anthropology

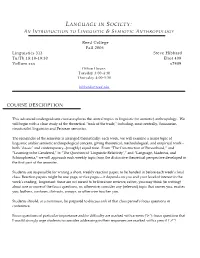

LANGUAGE IN SOCIETY: AN INTRODUCTION TO LINGUISTIC & SEMIOTIC ANTHROPOLOGY Reed College Fall 2006 Linguistics 313 Steve Hibbard Tu/Th 18:10‐19:30 Eliot 409 Vollum xxx x7489 Office Hours: Tuesday 3:00‐4:30 Thursday 4:00‐5:30 [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION This advanced undergraduate course explores the central topics in linguistic (or semiotic) anthropology. We will begin with a close study of the theoretical ʺtools of the trade,ʺ including, most centrally, Saussurian structuralist linguistics and Peircean semiotics. The remainder of the semester is arranged thematically: each week, we will examine a major topic of linguistic and/or semiotic anthropological concern, giving theoretical, methodological, and empirical work‐‐ both ʺclassicʺ and contemporary‐‐(roughly) equal time. From “The Construction of Personhood,” and “Learning to be Gendered,” to “The Question of ‘Linguistic Relativity’,” and “Language, Madness, and Schizophrenia,” we will approach each weekly topic from the distinctive theoretical perspective developed in the first part of the semester. Students are responsible for writing a short, weekly reaction paper, to be handed in before each week’s final class. Reaction papers might be one page, or five pages—it depends on you and your level of interest in the week’s reading. Important: these are not meant to be literature reviews; rather, you may think (in writing) about one or more of the focus questions, or, otherwise, consider any (relevant) topic that moves you, excites you, bothers, confuses, distracts, annoys, or otherwise touches you. Students should, at a minimum, be prepared to discuss each of that class period’s focus questions in conference.