Lives As Revelatory Texts: Constructing a Spiritual Biography of Arleen Mccarty Hynes, O.S.B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NO MARK 10:45 CHANGES Partment

THE BAGPIPE MONDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2017 14049 SCENIC HIGHWAY, LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN, GA 30750 VOLUME 64.3 Debate Club FIDC NBA Better than Star Wars? Open Letter Covenant’s team took home silver Covenant students attended three- A look at some key individuals in Aline Sluis spotlights Valerian and The skates VS. blades debate con- at Denver invitational day community development the 2016-17 NBA season the City of a Thousand Planets tinues in a fiery exchange conference Page 2 Page 2 Page 4 Page 5 Page 8 COMPETETIVE SCHOLARSHIPS MODIFIED by Greer McCollum College administration is majorly altering sever- al merit-based scholar- ships—including the Ma- clellan and Wilberforce scholarships and depart- mental scholarships—and is creating the Presidential scholarship, a $5000 mer- it-based award. The changes are partly an initiative by members of the Admissions office, who saw larger, more mon- eyed universities drawing photo by Cressie Tambling brilliant applicants away with full-ride scholarship offers. “I would hate for a student who wants to be at Covenant to not be at Covenant because they WIC LECTURE RECAP felt a full tuition scholar- by Roy Uptain the chapel hall, was “Vain kinda wanting to one-up a subdivision of the PCA’s ship [to another college] Glory.” During one of or add your take or what- Discipleship Ministries was more attractive or do- If your roommate starts the class lectures she re- ever, she was like ‘do this (CDM), are not necessari- able for their family,” said carrying a rock around in counted how she has her practice and you are going ly supposed to be given by Director of Admissions their mouth you can thank students suck on a tic- to see how much you do women or be about wom- Scott Schindler. -

Subjectivity in American Popular Metal: Contemporary Gothic, the Body, the Grotesque, and the Child

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Glasgow Theses Service Subjectivity In American Popular Metal: Contemporary Gothic, The Body, The Grotesque, and The Child. Sara Ann Thomas MA (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow January 2009 © Sara Thomas 2009 Abstract This thesis examines the subject in Popular American Metal music and culture during the period 1994-2004, concentrating on key artists of the period: Korn, Slipknot, Marilyn Manson, Nine Inch Nails, Tura Satana and My Ruin. Starting from the premise that the subject is consistently portrayed as being at a time of crisis, the thesis draws on textual analysis as an under appreciated approach to popular music, supplemented by theories of stardom in order to examine subjectivity. The study is situated in the context of the growing area of the contemporary gothic, and produces a model of subjectivity specific to this period: the contemporary gothic subject. This model is then used throughout to explore recurrent themes and richly symbolic elements of the music and culture: the body, pain and violence, the grotesque and the monstrous, and the figure of the child, representing a usage of the contemporary gothic that has not previously been attempted. Attention is also paid throughout to the specific late capitalist American cultural context in which the work of these artists is situated, and gives attention to the contradictions inherent in a musical form which is couched in commodity culture but which is highly invested in notions of the ‘Alternative’. In the first chapter I propose the model of the contemporary gothic subject for application to the work of Popular Metal artists of the period, drawing on established theories of the contemporary gothic and Michel Foucault’s theory of confession. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Music 2016 ADDENDUM This Catalog Includes New Sheet Music, Songbooks, and Instructional Titles for 2016

Music 2016 HAL LEONARD ADDENDUM This catalog includes new sheet music, songbooks, and instructional titles for 2016. Please be sure to see our separate catalogs for new releases in Recording and Live Sound as well as Accessories, Instruments and Gifts. See the back cover of this catalog for a complete list of all available Hal Leonard Catalogs. 1153278 Guts.indd 1 12/14/15 4:15 PM 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Sheet Music .........................................................3 Piano .................................................................53 Musicians Institute ............................................86 Fake Books ........................................................4 E-Z Play Today ...................................................68 Guitar Publications ............................................87 Personality .........................................................7 Organ ................................................................69 Bass Publications ............................................102 Songwriter Collections .......................................21 Accordion..........................................................70 Folk Publications .............................................104 Mixed Folios ......................................................23 Instrumental Publications ..................................71 Vocal Publications .............................................48 Berklee Press ....................................................85 INDEX: Accordion..........................................................70 -

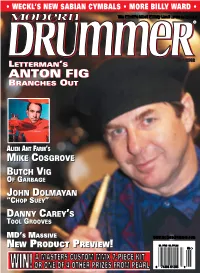

June 2002 BBRANCHESRANCHES OOUTUT

• WECKL’S NEW SABIAN CYMBALS • MORE BILLY WARD • LLETTERMANETTERMAN’’SS ANTANTONON FIGFIG June 2002 BBRANCHESRANCHES OOUTUT AALIENLIEN AANTNT FFARMARM’’SS MMIKEIKE CCOSGROVEOSGROVE BBUTCHUTCH VVIGIG OOFF GGARBAGEARBAGE JJOHNOHN DDOLMAOLMAYYANAN “C“CHOPHOP SSUEYUEY”” DDANNYANNY CCAREYAREY’’SS TTOOLOOL GGROOVESROOVES MD’MD’SS MMASSIVEASSIVE NEW PRODUCT PREVIEW! $4.99US $6.99CAN NEW PRODUCT PREVIEW! 06 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 26, Number 6 David Letterman’s ANTON FIG Obscure South African drummer becomes first-call drummer for New York’s most prestigious gigs. Read all about it. by Robyn Flans 38 Paul La Raia Alien Ant Farm’s UPDATE 20 MIKE COSGROVE Sveti’s Marko Djordjevic The AAF formula for heavy-rock success? Ghetto beats, a Michael 52 CPR’s Stevie Di Stanislao Jackson cover, and work, work, Willie Nelson’s Paul & Billy English Alex Solca and more work. by David John Farinella Japanese Tabla Synthesist Asa-Chang Warrant’s Mike Fasano Garbage’s Lamb Of God’s Chris Adler BUTCH VIG That rare artist with platinum experi- ROM HE AST ence on both sides of the glass, 62 F T P 132 Butch Vig knows of what he speaks. WEST COAST BEBOP PIONEER Alex Solca by Adam Budofsky ROY PORTER He carried first-hand knowledge from Charlie Parker to the West Coast, and helped MD’S PRODUCT EXTRAVAGANZA usher in a new chapter in jazz history. by Burt Korall Gearheads of the world, this is your issue! WOODSHED 138 76 CHRIS VRENNA Running on caffeine and plenty of ROM, ex–Nine Inch Nails drummer Chris Vrenna creates sonic scenarios unlike anything you’ve heard. -

Hallo Zusammen

Hallo zusammen, Weihnachten steht vor der Tür! Damit dann auch alles mit den Geschenken klappt, bestellt bitte bis spätestens Freitag, den 12.12.! Bei nachträglich eingehenden Bestellungen können wir keine Gewähr übernehmen, dass die Sachen noch rechtzeitig bis Weihnachten eintrudeln! Vom 24.12. bis einschließlich 5.1.04 bleibt unser Mailorder geschlossen. Ab dem 6.1. sind wir aber wieder für euch da. Und noch eine generelle Anmerkung zum Schluss: Dieser Katalog offeriert nur ein Bruchteil unseres Gesamtangebotes. Falls ihr also etwas im vorliegenden Prospekt nicht findet, schaut einfach unter www.visions.de nach, schreibt ein E-Mail oder ruft kurz an. Viel Spass beim Stöbern wünscht, Udo Boll (VISIONS Mailorder-Boss) NEUERSCHEINUNGEN • CDs VON A-Z • VINYL • CD-ANGEBOTE • MERCHANDISE • BÜCHER • DVDs ! CD-Angebote 8,90 12,90 9,90 9,90 9,90 9,90 12,90 Bad Astronaut Black Rebel Motorcycle Club Cave In Cash, Johnny Cash, Johnny Elbow Jimmy Eat World Acrophobe dto. Antenna American Rec. 2: Unchained American Rec. 3: Solitary Man Cast Of Thousands Bleed American 12,90 7,90 12,90 9,90 12,90 8,90 12,90 Mother Tongue Oasis Queens Of The Stone Age Radiohead Sevendust T(I)NC …Trail Of Dead Ghost Note Be Here Now Rated R Amnesiac Seasons Bigger Cages, Longer Chains Source Tags & Codes 4 Lyn - dto. 10,90 An einem Sonntag im April 10,90 Limp Bizkit - Significant Other 11,90 Plant, Robert - Dreamland 12,90 3 Doors Down - The Better Life 12,90 Element Of Crime - Damals hinterm Mond 10,90 Limp Bizkit - Three Dollar Bill Y’all 8,90 Polyphonic Spree - Absolute Beginner -Bambule 10,90 Element Of Crime - Die schönen Rosen 10,90 Linkin Park - Reanimation 12,90 The Beginning Stages Of 12,90 Aerosmith - Greatest Hits 7,90 Element Of Crime - Live - Secret Samadhi 12,90 Portishead - PNYC 12,90 Aerosmith - Just Push Play 11,90 Freedom, Love & Hapiness 10,90 Live - Throwing Cooper 12,90 Portishead - dto. -

Poetry and Fiction, Both Within Our University of Hawai`I at Mänoa Community and Beyond

Hawai‘i Review 76 Spring 2012 The Journal Hawai`i Review is a publication of the Board of Publica- tions of the University of Hawai`i at Mänoa. It reflects only the views of its editors and contributors, who are soley responsible for its content. Hawai`i Review, a mem- ber of the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines, is indexed by the Humanities International Index, the Index of American Periodical Verse, Writer’s Market, and Poet’s Market. Administrative and Technical Support Jay Hartwell, Robert Reilly, Sandy Matsui, Ka Leo, the U.H.M. Board of Publications, and the U.H.M. English Department. Subscriptions If you enjoy our journal, please subscribe. Domestic rates: one issue - $10; one year (2 issues) - $20; two years (4 issues) - $40. Subscriptions will be mailed at bookrate. Address all subscription requests to: Hawai`i Review, 2445 Campus Road, Hemenway Hall 107, Honolulu, HI 96822. Advertising rates available upon request. Visit http://www.kaleo.org/hawaii_review or email us at [email protected] for more information. © 2012 by the Board of Publications, University of Hawai`i at Mänoa. All rights revert to the writers and art- ists upon publication. All requests for reproduction and other propositions should be directed to the writers and the artist. ISSN: 0093-9625 Cover Art: Darren W. Brown Internal Art: Darren W. Brown Dear Reader, This issue of Hawai`i Review focuses on the idea of place - rootedness, lived lives, being at home. We’ve chosen artwork that celebrates our home, here in Hawai`i, and are sure that you will enjoy its natural beauty. -

CD Review: Able Thought’S Serene in Limbo

CD Review: Able Thought’s serene In Limbo Local one-man band Able Thought brings a dose of tranquility to the Providence music scene with his latest album, serene In Limbo. People like Andrew Bird and Kishi Bashi have made looping an art form and removed the need for a backing band to produce a full sound. Able Thought uses a loop pedal — I’m assuming — to create his own brand of atmospheric, low-fi folk. What’s striking on first-listen is the use of a nylon string classical guitar as a specific choice. Where folk musicians usually swear by the metal strings, Able Thought embraces the nylon, giving serene In Limbo a signature sound. The guitar playing sounds like a mix of fingerstyle and traditional picking that works well, especially in songs like “In Limbo” and “Places.” But the ambient quality that attracts people to this kind of music has a way of mashing the songs together and making it hard to differentiate one from the next. The level of manipulation makes me wonder if they’d be recognizable played with no effects. To be fair, this gripe is more of a comment on the musical style; I have been accused of not being able to enjoy “chill” music, but many artists these days seem to be drowning themselves in ever-increasing levels of reverb. Maybe the best way to describe the sound is by simply recalling the name of the album. You feel like you’re floating in limbo in some echo-y, open forest. With tons of reverb. -

Brooks Wackerman, Brings a Most Assured Sense of Groove to BOB BERENSON Or (815) 732-5283

!350%2 #/,/33!, 7). 02):%0!#+!'% 41&$*"-%36..&3-&"%&3$%306/%61 &ROM'RETSCH 3ABIAN 'IBRALTAR ,0 4OCA AND0ROTECTION2ACKET 6ALUED AT/VER !UGUST 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE *.1307& :0635*.& *-"/36#*/ 3&13&4&/5*/(5)&/&8 %36..*/(3&(*.& 36'64i41&&%:w+0/&4 %6,&&--*/(50/4 53"(*$"$30#"5 #"%3&-*(*0/4 )*()"35 7"/%&3(3""'4 #300,4 16/,30$, (6:&7"/4130(03*(*/"- 8"$,&3."/ $".$0'03$0--&$5034 "-,"-*/&53*04%&3&,(3"/5(&"3*/(61 "-"/1"340/45)&130+&$50'3&$03%*/(%36.4 -ODERN$RUMMERCOM 3&7*&8&% :".")"$-6#$6450.(*(.",&3;*-%+*"/"48*4),/0$,&3;$)*/"4MM -13*$"3%$"+0/.*$4:45&..00/.*$4 Volume 35, Number 8 • Cover photo by Alex Solca CONTENTS Alex Solca Alex Solca 34 ILAN RUBIN 42 BROOKS He appeared in the Guinness record book, performed at the Modern Drummer Fest, and toured with Nine Inch Nails before he could legally buy a drink. MD checks in with the prodigious multi-instrumentalist, who recently released his WACKERMAN ambitious second solo album. After having served Infectious Grooves, the Vandals, Suicidal Tendencies, Tenacious D, and Korn with honor, he’s now celebrating a decade of bringing rare refinement to the pioneering punk of Bad Religion. Joe Del Tufo 12 Update NYC Jazzer MARK FERBER UFO’s ANDY PARKER Duff McKagan’s ISAAC CARPENTER Justin Bieber’s MELVIN BALDWIN Dropkick Murphys’ MATT KELLY Robert Caplin 30 A Different View Producer/Bandleader ALAN PARSONS 72 Portraits Avant/Rock Independent CHES SMITH 52 GUY EVANS 76 Woodshed Driven by its longtime drummer’s galvanizing performances, Drummer/Producer BOBBY MACINTYRE’s Studio 71 the iconic British prog band Van der Graaf Generator is as intense and unpredictable as ever. -

Dan Sperry Joins the Illusionists at PPAC,Slipknot and Korn At

Alt-Nation: Metalachi — This Week! Have you ever listened to 94 WHJY during the day and wondered what would be like if their staid playlist was performed by a mariachi band? Me neither. That said, Metalachi, known as the greatest heavy metal mariachi band ever to roam the earth, does sound like a hoot! Metalachi recreates classic rock staples and heavy metal anthems as mariachi ditties and it is downright awesome! On their debut album, Uno, Metalachi tackle 8 classics by the likes of Guns ‘N’ Roses, Scorpions, Bon Jovi and more! Check out their version of Ozzy Osbourne’s “Crazy Train” here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g_5y5KrBoO8 and don’t miss Metalachi this Wednesday at Firehouse 13! Metalachi and Lame Genie rock Firehouse 13 on Jan 14. Email music news to [email protected] Mystery, Wonder and Awe, “O” My! Just over the Massachusetts state border in Fall River, 20 or so highly skilled and dedicated classical singers gather weekly to rehearse the complex and beautiful vocal music of various composers. This group calls itself “Sine Nomine,” which translates to “Without a Name.” Founded in 1993 by early music specialist Glenn Giuttari, Sine Nomine has been in existence for over 20 years. Joseph Fort, Sine Nomine’s new music director, is currently a PhD candidate in music theory at Harvard University. He is a graduate of Cambridge University and also has studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London. A mild-mannered man full of musical integrity, Fort has been involved in choral music his entire professional life, both as a director and as an accompanist. -

Creator of New NAIT Confessions Page Speaks, P. 16

THE NUGGET IS TAKING A WEEK OFF FOR MIDTERMS – NEXT ISSUE NOV. 5! THE Thursday, October 22, 2015 Volume 53, Issue 8 NAIT YOUR STUDENT NEWSPAPERNUGGET FOR MORE THAN 50 YEARS, EDMONTON, ALBERTA, CANADA TBH CONFESSES Creator of new NAIT confessions page speaks, p. 16 Graphic design by Connor O’Donovan 2 The Nugget Thursday, October 22, 2015 NEWS&FEATURES Hoping for more space It’s not just food services or technol- ogy areas that are feeling the pinch. Wan- der down the E Hallway and you can see many students crammed into the small study areas offset in the adjoining halls. Some students resort to lining the hall- ways, sitting on the floor to study or snack between classes. Have a group project to complete? There are precious few loca- tions on campus where you can gather NICOLAS BROWN quietly to collaborate, mostly limited to Issues Editor the new Teaching and Learning Commons @bruchev on the north-end of campus. We can just Space, just like time, appears to be a ignore the limited space available for stu- finite resource on campus at NAIT. Stu- dents to organize social activities, since dents everywhere are feeling the squeeze that could take an entire article in itself, and it might not be getting better any time but NAITSA’s limited office space is soon. indicative of that issue. As NAIT’s enrolment continues to Certainly, NAIT’s continued expan- grow, it feels like we’re finding less and sion, with the addition of the new HET less space on campus. Trying to access a building and the planned opening of the mikeroeconomics.blogspot.com computer workstation at the HP Centre CAT Building in Fall 2016, will have vacated space? No doubt more programs between classes doesn’t mean more space. -

R 35.00(Incl.)

www.prophecy.co.za March 2003 | Volume 5 Issue 12 SA Edition R 35.00 (Incl.) C O N T E N T S FEATURES PlayStation SA Interview 18 Hardcore Mouse Roundup 80 Unreal Tournament 2003: Level Editing 92 PREVIEWS Freelancer 38 Tropico 2: Pirate Cove 42 Blitzkrieg 42 KnightShift 44 Robin Hood: Defender of the Crown 46 Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners 50 Hannibal 52 PC REVIEWS Sim City 4 56 Scrabble 2003 60 Project Nomads 62 Star Trek: Starfleet Command III 64 Tiger Woods PGA Tour 2003 66 Elder Scrolls 3: Tribunal 67 CONSOLE REVIEWS Tekken 4 (PS2) 68 WRC II Extreme (PS2) 70 Ed’s Note 6 S The Simpsons Skateboarding (PS2) 70 Inbox 8 R A WWE Smackdown: Shut Your Mouth (PS2) 71 Domain of The_Basilisk 10 L X-Men: Next Dimension (PS2) 71 Freeloader 11 U Spyro: Enter the Dragonfly (PS2) 72 G Role Playing 12 E Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 4 (PS2) 72 Anime 14 R Resident Evil: Code Veronica X (PS2) 74 Lazy Gamer’s Guide: PC Case 16 Legion: Legend of Excalibur (PS2) 74 Community.co.za 20 Metroid Fusion (GBA) 75 PC News 26 Monster Force (GBA) 75 Console News 30 Spyro: Season of Ice (GBA) 76 Technology News 34 Spyro 2: Season of Flame (GBA) 76 The Awards 54 Super Mario Sunshine (GCN) 77 Competition: Splinter Cell & TOCA Race Driver 61 Mario Party 4 (GCN) 77 Subscriptions 79 NFS Hot Pursuit 2 (XBox) 78 The Web 94 SSX Tricky (XBox) 78 Leisure Reviews - Music & DVDs 96 Send Off 98 Creative CardCam Value 86 E Creative PC-Cam 550 86 R Logitech GameCube Force Feedback Wheel 87 A W GameCube Wavebird 87 D Logitech z-640 speakers 87 R Logitech MOMO Force Feedback Wheel 88 A Hey-Ban Flat Speaker System 88 H Shuttle XPC 89 Creative I-trigue 2.1 Speakers 89 A-Open H600B Computer Housing 90 This month’s cover: Tekken 4 - Go to A-Open Sound Activated Fluorescent Lamp 90 page 68 now! Mouse Bungee 90 March NAG Cover CD DEMOS Chain Reaction 4.1 MB Enclave 190 MB IGI 2 Covert Strike 138 MB MOVIES Freelancer 10 MB The Animatrix: Second Rennaisance Part 1 141 MB The Matrix Reloaded Trailer 23.9 MB PATCHES Battlefield 1942 Patch v13.exe 47 MB Morrowind Tribunal v1.4.1313.