Combat Service Support Force Protection in the Asymmetric Battle Space: Who Should Own the Task?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grizzly FALL-WINTER 2020

41 CANADIAN BRIGADE GROUP THE GRIZZLY FALL-WINTER 2020 If you have an interesting story, be it in or Everyone has a story out of uniform and want to share it, 41 CBG Tell yours Public Affairs wants to hear from you. For more information on how to get your story published in The Grizzly, contact: Captain Derrick Forsythe Public Affairs Officer 41 Canadian Brigade Group Headquarters Email: [email protected] Telephone: 780-288-7932 or 780-643-6306 Submission deadline for the next edition is 14 May 2021. Photos should be 3 MB or larger for best resolution. Changes of Command + 41 TBG and Brigade Battle school + + DEPLOYING -Individual Augmentation + Boot Review + Exericses - UNIFIED GUNNER I, and CREW FOX ALBERTA’s BRIGADE 41 CANADIAN BRIGADE GROUP ICE CLIMBING • SNOWSHOEING • SKI MOUNTAINEERING EXERCISE GRIZZLY ADVENTURE THEFALL-WINTER 2020 GRIZZLY 13-19 FEBRUARY 21 IN THIS ISSUE .6 Changes of Command .10 BOOT REVIEW - LOWA Z-8S, Rocky S2V, and Salomon Guardian. .12 41 Territorial Battalion Group and 41 Brigade Battle School .16 WARHEADS ON FOREHEADS! LET ‘ER BUCK! - Mortar Course .18 Alberta’s Gunners come together for Ex UNIFIED GUNNER I .22 Podcast Review - Hardcore History .26 Honours and Awards .26 Exercise CREW FOX .26 DEPLOYING - Individual Augmentation .34 PSP: Pre-BMQ/PLQ Workouts THE COVer The cover art was illustrated and coloured by Corporal Reid Fischer from the Calgary Highlanders. The Grizzly is produced by 41 Canadian Brigade Group Public Affairs. Editor - Captain Matthew Sherlock-Hubbard, 41 Canadian Brigade Group Public Affairs Officer Layout - Captain Brad Young, 20 Independent Field Battery, RCA For more information about The Grizzly, contact Captain Derrick Forsythe, Public Affairs Officer, 41 Canadian Brigade Group Headquarters [email protected] or 780-288-7932 1 From the Commander “May you live in interesting times,” is allegedly an ancient Chinese We had 450 members of the Brigade volunteer for Class C With this in mind, we will conduct a centralized Brigade curse. -

Military) (MSM)

MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL (Military) (MSM) CITATIONS 2008 UPDATED: 18 June 2019 PAGES: 48 CORRECT TO: 26 January 2008 (CG) 01 March 2008 (CG) 19 April 2008 (CG) 19 July 2008 (CG) 29 November 2008 (CG) Prepared by John Blatherwick, CM, CStJ, OBC, CD, MD, FRCP(C), LLD(Hon) Brigadier-General Shane Anthony Brennan, MSC*, CD Colonel Pierre Huet, MSM*, CD 1 MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL (Military Division) (MSM) To CANADIAN FORCES MILITARY MEMBERS Canada Gazette 2008 CANADA GAZETTE NAME RANK UNIT DECORATIONS 20 ABBOTT, Peter Gerald Colonel Cdr Task Force El Gorah Sinai OMM MSM CD 34 ALAIN, Julie Marie Micheline Corporal CFHS Afghanistan MSM 34 ARCAND, Gilles CWO RSM JTF Afghanistan MMM MSM CD 04 BARNES, John Gerard MWO ‘C’ Coy 1 RCR Afghanistan MMM MSM CD 06 BARTLETT, Stephen Stanley CWO RSM Task Force Afghanistan MSM CD 20 BELL, Steven Albert Commander First OIC Maritime Amphibious Unit MSM CD 38 BERGERON, Joseph Jean-Pierre LCol Israel-Hezbollah conflict in 2006 MSM CD 38 BERREA, Patrick James Corporal Mass Distribution Cdn Medals MSM 25 BERRY, David Brian LCol Advisor Afghan Minister Rehab MSM CD 24 BÉRUBÉ, Jules Joseph Jean WO 2nd RCR JTF Afghanistan MSM CD 05 BISAILLON, Joseph Martin François Major DCO Mentor Team Afghanistan MSM CD 35 BOURQUE, Dennie Captain FOO F22eR Afghanistan MSM 21 BOWES, Stephen Joseph Colonel DCO Contingency Task Force MSC MSM CD 24 BRADLEY, Thomas Major Chief Ops JTF Afghanistan HQ MSM CD 38 BRENNAN, James Captain Strategic Airfield Planner 2007 MSM CD 35 BRÛLE, Pierre Jr. Corporal 53 rd Engineer Sqd Afghanistan MSM -

Keri L. Kettle

KERI L. KETTLE Assistant Professor, Marketing Cell: 305-494-5207; Work: 305-284-6849 School of Business Administration, U of Miami e-mail: [email protected] Coral Gables, Florida, 33134 URL: www.kerikettle.com/ ACADEMIC POSITIONS Assistant Professor of Marketing Asper School of Business, University of Manitoba, 2016 - present Assistant Professor of Marketing School of Business Administration, University of Miami, 2011 - 2016 EDUCATION PhD, Marketing, School of Business, University of Alberta, 2011 MBA, Marketing, University of Calgary, 2003 BA, Honours, Business Administration, Royal Military College of Canada, 1997 PUBLICATIONS Kettle, Keri L., Remi Trudel, Simon J. Blanchard, and Gerald Häubl, “Putting All Eggs into the Smallest Basket: Repayment Concentration and Consumer Motivation to Get Out of Debt,” forthcoming at Journal of Consumer Research. Kettle, Keri L., and Gerald Häubl (2011), “The Signature Effect: Signing One’s Name Influences Consumption-Related Behavior by Priming Self-Identity,” Journal of Consumer Research, 38 (3), 474-489. Kettle, Keri L., and Gerald Häubl (2010), “Motivation by Anticipation: Expecting Rapid Feedback Enhances Performance,” Psychological Science, 31 (2), 545-547. RESEARCH UNDER REVIEW Kettle, Keri L., Gerald Häubl, and Isabelle Engeler, “Performance-Enhancing Social Contexts: When Sharing Predictions About One’s Performance is Motivating,” invited for resubmission (2nd round) at Journal of Consumer Research. Kettle, Keri L., Katherine E. Loveland, and Gerald Häubl, “The Role of the Self in Self- Regulation: Self-Concept Activation Disinhibits Food Consumption Among Restrained Eaters,” invited for resubmission (2nd round) at Journal of Consumer Psychology. CV – Keri L. Kettle – Page 1 of 8 Kettle, Keri L., and Anthony Salerno, “Anger Promotes Economic Conservatism,” currently under review (1st round) at Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. -

12 (Vancouver) Field Ambulance

Appendix 5 Commanding Officers Rank Name Dates Decorations / WWII 12 Canadian Light Field Ambulance LCol BALDWIN, Sid 1941 to 1942 LCol TIEMAN, Eugene Edward (‘Tuffie’) 1942 to 1943 OBE SBStJ 1 LCol CAVERHILL, Mervyn Ritchie (‘Merv’) 1943 to 1944 OBE LCol McPHERSON, Alexander Donald (‘Don’) 1944 to 1945 DSO Psychiatrist Post-War 12 Field Ambulance LCol CAVERHILL, Mervyn Ritchie (‘Merv’) 1946 to 1946 OBE CO #66 Canadian General Hospital (Which was merged with 24 Medical Company) LCol HUGGARD, Roy 1946 to 1947 24 Medical Company LCol MacLAREN, R. Douglas (‘Doug’) 1947 to 1950 LCol SUTHERLAND, William H. (‘Bill”) 1950 to 1954 LCol ROBINSON, Cecil (‘Cec’) Ernest G. 1954 to 1958 CD QHP Internal Medicine LCol STANSFIELD, Hugh 1958 to 1961 SBStJ CD 2 LCol BOWMER, Ernest John (‘Ernie’) 1961 to 1966 MC CD Director Prov Lab OC Medical Platoon 12 Service Battalion Major NOHEL, Ivan 1976 to 1979 12 (Vancouver) Medical Company Major NOHEL, Ivan 1979 to 1981 CD Major WARRINGTON, Michael (‘Mike’) 1981 to 1983 OStJ CD GP North Van Major GARRY, John 1983 to 1986 CD MHO Richmond LCol DELANEY, Sheila 1986 to 1988 CD Nurse 3 LCol O’CONNOR, Brian 1988 to 1991 CD MHO North Shore LCol FRENCH, Adrian 1991 to 1995 CD LCol WEGENER, Roderick (‘Rod’) Charles 1995 to 2000 CD 12 (Vancouver) Field Ambulance LCol LOWE, David (‘Dave’) Michael 2000 to 2008 CD ESM Peace Officer LCol NEEDHAM, Rodney (‘Rod’) Earl 2008 to 2010 CD Teacher in Surrey LCol ROTH, Ben William Lloyd 2010 to 2014 CD USA MSM LCol FARRELL, Paul 2014 to 2016 CD ex RAMC LCol McCLELLAND, Heather 2016 to present CD Nursing Officer 1 Colonel Tieman remained in the RCAMC after the war and was the Command Surgeon Eastern Army Command in 1954; he was made a Serving Brother of the Order of St. -

The Strathconian

The Strathconian2011 TTHEHE SSTRATHCONIANTRATHCONIAN LLordord SStrathcona’strathcona’s HHorseorse Allied with The Queen’s Royal Lancers ((RoyalRoyal CCanadians)anadians) Partnered with 10 (Polish) Armour Cavalry Brigade 1900 ~ 2011 EXCELLENCE DEFINED MEET THEBURKEGROUP OFCOMPANIES :I@@ďG9FJ=79ďC::G9HďDF=BH=B; annual reports, manuals, brochures, magazines, books, calendars, maps SMALLFORMAT OFFSETPRINTING &FINISHING foormms,s business cards, leerheh ad & envveloppes WIDEFORMAT DISPLAYGRAPHICS banners, exterior/interir orr signs, didispplaysy 8=;=H5@ďDF=BH=B;ďďA5=@ďG9FJ=79G print on demand & personalized direct mailing Dedication, desire, commitment and leadership - qualities the people of ATCO Douglas Printing is proud to be FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) Chain-of-Custody Certified. When you and Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadian) have in common. buy products with the FSC logo, you’re guaranteed your purchase is supporting healthy forests and strong Wcaaib]h]Yg"GK!7C7!$$&')-kkk"ZgWWUbUXU"cf[%--*:cfYghGhYkUfXg\]d7cibW]`5"7" %$,$,%&$GhfYYh 9Xacbhcb567UbUXUH)<'D- ėėėď5ďHF58=H=CBďC:ďEI5@=HMď HY`.+,$!(,&!*$&*#%!,$$!,'+!%'-):Ul.+,$!(,,!$%$* douglasprint.com 5B8ď7F5:HGA5BG<=D www.atco.com Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians) Battle Honours South Africa South Africa, 1900 - 1901 First World War Festubert 1915, Somme 1916, ’18; Brazentin, Pozières, Flers-Courcelette, Cambrai 1917, ’18; St. Quentin, Amiens, Hindenberg Line, St. Quentin Canal, Beaurevoir, Pursuit to Mons, France and Flanders 1915 - 1918 Second World War Liri Valley, Melfa -

The Perception Versus the Iraq War Military Involvement in Sean M. Maloney, Ph.D

Are We Really Just: Peacekeepers? The Perception Versus the Reality of Canadian Military Involvement in the Iraq War Sean M. Maloney, Ph.D. IRPP Working Paper Series no. 2003-02 1470 Peel Suite 200 Montréal Québec H3A 1T1 514.985.2461 514.985.2559 fax www.irpp.org 1 Are We Really Just Peacekeepers? The Perception Versus the Reality of Canadian Military Involvement in the Iraq War Sean M. Maloney, Ph.D. Part of the IRPP research program on National Security and Military Interoperability Dr. Sean M. Maloney is the Strategic Studies Advisor to the Canadian Defence Academy and teaches in the War Studies Program at the Royal Military College. He served in Germany as the historian for the Canadian Army’s NATO forces and is the author of several books, including War Without Battles: Canada’s NATO Brigade in Germany 1951-1993; the controversial Canada and UN Peacekeeping: Cold War by Other Means 1945-1970; and the forthcoming Operation KINETIC: The Canadians in Kosovo 1999-2000. Dr. Maloney has conducted extensive field research on Canadian and coalition military operations throughout the Balkans, the Middle East and Southwest Asia. Abstract The Chrétien government decided that Canada would not participate in Operation Iraqi Freedom, despite the fac ts that Canada had substantial national security interests in the removal of the Saddam Hussein regime and Canadian military resources had been deployed throughout the 1990s to contain it. Several arguments have been raised to justify that decision. First, Canada is a peacekeeping nation and doesn’t fight wars. Second, Canada was about to commit military forces to what the government called a “UN peacekeeping mission” in Kabul, Afghanistan, implying there were not enough military forces to do both, so a choice had to be made between “warfighting” and “peacekeeping.” Third, the Canadian Forces is not equipped to fight a war. -

TRAINING to FIGHT and WIN: TRAINING in the CANADIAN ARMY (Edition 2, May 2001)

ttrainingraining ttoo fightfight andand wwin:in: ttrainingraining inin thethe canadiancanadian aarrmymy Brigadier-General Ernest B. Beno, OMM, CD (Retired) Foreword by Brigadier-General S.V. Radley-Walters, CMM, DSO, MC, CD Copyright © Ernest B. Beno, OMM, CD Brigadier-General (Retired) Kingston, Ontario March 22, 1999 (Retired) TRAINING TO FIGHT AND WIN: TRAINING IN THE CANADIAN ARMY (Edition 2, May 2001) Brigadier-General Ernest B. Beno, OMM, CD (Retired) Foreword By Brigadier-General S.V. Radley-Walters, CMM, DSO, MC, CD (Retired) TRAINING TO FIGHT AND WIN: TRAINING IN THE CANADIAN ARMY COMMENTS AND COMMENTARY “I don’t have much to add other than to support the notion that the good officer is almost always a good teacher.” • Lieutenant-Colonel, (Retired), Dr. Doug Bland, CD Queen’s University “ Your booklet was a superb read, packed with vital lessons for our future army - Regular and Reserve!” • Brigadier-General (Retired) Peter Cameron, OMM, CD Honorary Colonel, The 48th Highlanders of Canada Co-Chair Reserves 2000 “This should be mandatory reading for anyone, anywhere before they plan and conduct training.” • Lieutenant-Colonel Dave Chupick, CD Australia “I believe that your booklet is essential to the proper conduct of training in the Army, and I applaud your initiative in producing it. As an overall comment the individual training of a soldier should ensure the ability to ‘march, dig and shoot.’ If these basics are mastered then the specialty training and collective training can be the complete focus of the commander’s/CO’s concentration.” • Colonel (Retired) Dick Cowling London, ON “I think this is the first ‘modern’ look at training in the Canadian Army that I heard of for thirty years. -

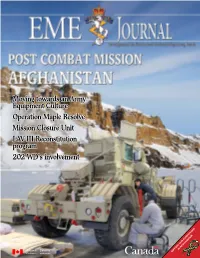

Operation Maple Resolve LAV III Reconstitution Program 202 WD's Involvement Moving Towards an Army Equipment Culture Mission C

Moving towards an Army Equipment Culture Operation Maple Resolve Mission Closure Unit LAV III Reconstitution program 202 WD’s involvement in Afghanistan support our companions EME Journal Regimental Command OST OMBAT ISSION FGHANISTAN 4 Branch Advisor’s Message EME P C M - A The need for an equipment culture and technological Moving towards an Army advice. 6 Equipment Culture Branch Chief Warrant Officer’s Exercise Maple Resolve 5 Message 8 Afghanistan is winding down and our skill-sets have Following years of combat and training specific to a become very specific, Ex Maple Resolve was the theatre of war, the EME Branch must now refocus perfect opportunity to address this issue. itself. 9 Mission Closure Unit 20 Learning and Action The LAV III Reconstitution 12 Operation Nanook 2011 10 program Op Nanook 2011 is one of the three major recurring With the end of the Kandahar mission the LAV III sovereignty Operations conducted annually by the CF LORIT fleet was pulled from theatre and shipped to in the North. London, Ontario for a re-set. 11 202 WD’s involvement What’s up? Trade Section 19 MOBILE trial on Ex Maple Resolve 26 Electronics and Optronics Tech The MOBILE solution permits Materiel Acquisition and 2012 EO Tech Focus Group Support (MA&S) activity in areas where connectivity to the DWAN is not available or is disrupted. 26 Materials Tech 14 Leopard 2A4M Course North American Technology Beyond the modular tent; a look at the trial of the On Oct 1st, 2011, twenty-four Mil and Civ students, 20 Demonstration 1000 Pers RTC Kitchen Project. -

Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 34 / PCEMI N°34 MASTER’S OF DEFENCE STUDIES RESEARCH PAPER OSCILLATIONS IN OBSCURITY: FORGING THE CANADIAN FORCES PARACHUTE SUPPORT CAPABILITY By / par Maj K.D. Brodie This paper was written by a student La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College in stagiaire du Collège des Forces fulfilment of one of the requirements of the canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des Course of Studies. The paper is a exigences du cours. L'étude est un scholastic document, and thus contains document qui se rapporte au cours et facts and opinions which the author alone contient donc des faits et des opinions que considered appropriate and correct for the seul l'auteur considère appropriés et subject. -

On the Cover

On the Cover: For the cover of Edition 1 - 2013: RCEME as Leaders Everywhere, Part 2, the editorial staff of the RCEME Journal wanted to focus on the five EME Branch leaders showcased in the Journal (Cover foreground from left to right: Col (Ret’d) Andrew Nellestyn, CWO Serge Froment, CWO Andy Dalcourt, BGen Alex Patch, BGen (Ret’d) Bill Brewer.) You can read interviews with these five individuals beginning on page 6. It was a challenge to select only a few leaders to interview out of the dozens of men and women who have made dramatic contributions to the EME world over the last decade. A decade is a very short time period to look at when considering the entire history of the EME Branch in Canada, even if we do restrict ourselves to the period from the founding of the EME Branch on 15 May 1944 to today. With that in mind we decided to add two other individuals to the cover of the Journal. General Andrew McNaughton CH, CB, CMG, DSO, CD, PC, and Colonel A.L. Maclean are two of the founding members of the EME trade in the Canadian Armed Forces and no discussion on today’s leadership would be complete without some mention of their contributions. These were two of the builders of the Branch and their influence is still being felt today. General Andrew McNaughton Colonel A.L. Maclean General McNaughton, an electrical engineer, joined the Canadian Colonel Maclean served 31 years in the Canadian Armed Forces during Armed Forces militia in 1909 and went overseas almost immediately which time he saw action in World War Two, rising to command the 1st following the beginning of hostilities of the First World War. -

Caf Logistics Force Protection

CAF LOGISTICS FORCE PROTECTION Major A.M. McCabe JCSP 40 PCEMI 40 Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and do Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs et not represent Department of National Defence or ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Ministère de Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used la Défense nationale ou des Forces canadiennes. Ce without written permission. papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par le Minister of National Defence, 2014. ministre de la Défense nationale, 2014. 1 CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 40 – PCEMI 40 SOLO FLIGHT CAF LOGISTICS FORCE PROTECTION: By Major A.M. McCabe Par le major A.M. McCabe “This paper was written by a student “La présente étude a été rédigée par attending the Canadian Forces College un stagiaire du Collège des Forces in fulfilment of one of the requirements canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des of the Course of Studies. The paper is exigences du cours. L'étude est un a scholastic document, and thus document qui se rapporte au cours et contains facts and opinions, which the contient donc des faits et des opinions author alone considered appropriate que seul l'auteur considère appropriés and correct for the subject. It does not et convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète necessarily reflect the policy or the pas nécessairement la politique ou opinion of any agency, including the l'opinion d'un organisme quelconque, y Government of Canada and the compris le gouvernement du Canada et Canadian Department of National le ministère de la Défense nationale du Defence. -

Close Engagement-Land Power in an Age of Uncertainty

Close Engagement Land Power in an Age of Uncertainty Evolving Adaptive Dispersed Operations CLOSE ENGAGEMENT LAND POWER IN AN AGE OF UNCERTAINTY Evolving Adaptive Dispersed Operations THE CANADIAN LAND OPERATIONS CAPSTONE OPERATING CONCEPT CLOSE ENGAGEMENT Land Power in an Age of Uncertainty Evolving Adaptive Dispersed Operations Canadian Army Land Warfare Centre Kingston, Ontario © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2019. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including scanning, photocopying, taping and recording, without the formal written consent of the copyright holder. Printed in Canada PUBLICATION DATA 1. Close Engagement – Land Power in an Age of Uncertainty – Evolving Adaptive Dispersed Operations Print NDID—B-GL-310-001/AG-001 ISBN—978-0-660-27740-0 GC Catalogue Number—D2-406/2019 Online NDID—B-GL-310-001/AG-001 ISBN—978-0-660-27741-7 GC Catalogue Number—D2-406/2019-PDF PUBLICATION DESIGN Army Publishing Office Kingston, Ontario NOTICE This documentation has been reviewed by the technical authority and does not contain controlled goods. Disclosure notices and handling instructions originally received with the document shall continue to apply. Cover Image Sources: Pixabay, Combat Camera FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................... 5 PURPOSE