President's Report.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obvious but Invisible: Ways of Knowing Health, Environment, and Colonialism in a West Coast Indigenous Community

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2018;60(2):241–273. 0010-4175/18 # Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History 2018 doi:10.1017/S001041751800004X Obvious but Invisible: Ways of Knowing Health, Environment, and Colonialism in a West Coast Indigenous Community PAIGE RAIBMON Department of History, University of British Columbia PRELUDE I: ABIRDS- EYE VIEW This is a story about divergent epistemologies and the politics of risk. It is a story about diverse ways of knowing a place, of sensing danger, of feeling well; a story about the production of imperception, the construction of colonial subjecthood, and the struggle for Indigenous sovereignty. In this story, an Indigenous community worked to render perceptible to the settler state appara- tus its knowledge claims about pollution, health, and critically, authority. Activ- ists initially pursued an anti-colonial, environmental justice campaign that sought to translate local, Indigenous ways of knowing into the epistemologies of environmental science and public health. This strategy earned them allies in the health science and legal professions, and activists had reason for optimism. Yet ultimately, this strategy failed. When it did, the community changed course: it now appropriated technologies of law rather than science. Where they previ- ously mobilized knowledge verifiable with bare human senses, they now Acknowledgments: I humbly acknowledge the many people whose generosity, assistance, and insights made this piece possible. Most importantly, I thank the Mowachaht and Muchalaht com- munity members who spoke and worked with me, especially but not only: Sheila Savey, Margarita James, Margaret Amos, Jerry Jack, Max Savey, Lillian Howard, and Mike Maquinna. -

Compensation After Delgamuukw Aboriginal Title’S Inescapable Economic Component

Compensation after Delgamuukw Aboriginal Title’s Inescapable Economic Component MICHAEL J. MCDONALD AND THOMAS LUTES Introduction As any observer of recent Canadian news can attest, aboriginal issues in Canada are once again atop the public and media agenda. The range of issues in the public eye is remarkable: from the applicability of sales tax to New Brunswick’s aboriginal peoples; to the return of traditional lands to the First Nation at Ipperwash, Ontario; to the unprecedented fusion of aboriginal healing circles and the Canadian justice system in British Columbia’s Bishop O’Connor case. While such stories ride the crest of the latest wave of national media attention, the land claims process in British Columbia remains some- what adrift following the December 1997 Delgamuukw decision. The im- plications of the Supreme Court of Canada’s ruling in Delgamuukw that aboriginal title exists and contains an “economic component” poses a tre- mendous challenge to government, private industry and First Nations. In particular, the Crown faces judgment for its action—or inaction—in Notes will be found on page 450. 425 426 Beyond the Nass Valley resolving land and resource claims, not only in our courts of law but also in the forum of public opinion, with its jury of voting citizens. The scenarios of economic doom voiced by a few politicians and public commentators since Delgamuukw was handed down have not al- layed British Columbians’ understandable concerns about the practical effects on their lives and on the effect of compensation to First Nations on the provincial economy. The entire land base of British Columbia is not about to be transferred to British Columbia’s First Nations, and the entire provincial budget for the next quarter-century will not be direct- ed to compensating the Province’s aboriginal peoples. -

Indigenous Perspectives Collection Bora Laskin Law Library

fintFenvir Indigenous Perspectives Collection Bora Laskin Law Library 2009-2019 B O R A L A S K I N L A W L IBRARY , U NIVERSITY OF T O R O N T O F A C U L T Y O F L A W 21 things you may not know about the Indian Act / Bob Joseph KE7709.2 .J67 2018. Course Reserves More Information Aboriginal law / Thomas Isaac. KE7709 .I823 2016 More Information The... annotated Indian Act and aboriginal constitutional provisions. KE7704.5 .A66 Most Recent in Course Reserves More Information Aboriginal autonomy and development in northern Quebec and Labrador / Colin H. Scott, [editor]. E78 .C2 A24 2001 More Information Aboriginal business : alliances in a remote Australian town / Kimberly Christen. GN667 .N6 C47 2009 More Information Aboriginal Canada revisited / Kerstin Knopf, editor. E78 .C2 A2422 2008 More Information Aboriginal child welfare, self-government and the rights of indigenous children : protecting the vulnerable under international law / by Sonia Harris-Short. K3248 .C55 H37 2012 More Information Aboriginal conditions : research as a foundation for public policy / edited by Jerry P. White, Paul S. Maxim, and Dan Beavon. E78 .C2 A2425 2003 More Information Aboriginal customary law : a source of common law title to land / Ulla Secher. KU659 .S43 2014 More Information Aboriginal education : current crisis and future alternatives / edited by Jerry P. White ... [et al.]. E96.2 .A24 2009 More Information Aboriginal education : fulfilling the promise / edited by Marlene Brant Castellano, Lynne Davis, and Louise Lahache. E96.2 .A25 2000 More Information Aboriginal health : a constitutional rights analysis / Yvonne Boyer. -

The Difficulties of Combating Inequality in Time

The Difficulties of Combating Inequality in Time Jane Jenson, Francesca Polletta & Paige Raibmon Abstract: Scholars have argued that disadvantaged groups face an impossible choice in their efforts to win policies capable of diminishing inequality: whether to emphasize their sameness to or difference from the advantaged group. We analyze three cases from the 1980s and 1990s in which reformers sought to avoid that dilemma and assert groups’ sameness and difference in novel ways: in U.S. policy on bio- medical research, in the European Union’s initiatives on gender equality, and in Canadian law on Indig- enous rights. In each case, however, the reforms adopted ultimately reproduced the sameness/difference dilemma rather than transcended it. To explain why, we show how profound disagreements about both the histories of the groups included in the policy and the place of the policy in a longer historical trajec- tory of reform either went unrecognized or were actively obscured. Targeted groups came to be attribut- ed a biological or timeless essence, not because this was inevitable, we argue, but because of these fail- ures to historicize inequality. Efforts to legislate or judicially confirm rights to equality often prove disappointing, even for those with clear-eyed aspirations. There are many rea- sons for the gap between the aspiration and the re- sult, but a deceptively simple one is that political actors define equality in ways that restrict its scope and substance. On some accounts, the problem can be characterized in terms of the sameness/differ- jane jenson is Professor Em- ence dilemma.1 Equality sometimes has been de- erita of Political Science at the fined as meaning that members of the disadvan- Université de Montréal. -

Court File No

S.C.C. FILE NO. 38734 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR BRITISH COLUMBIA) BETWEEN: HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN APPELLANT (Appellant) - and - RICHARD LEE DESAUTEL RESPONDENT (Respondent) - and - ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ONTARIO, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF QUEBEC, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW BRUNSWICK, ATTORNEY GENERAL FOR SASKATCHEWAN, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ALBERTA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE YUKON TERRITORY, PESKOTOMUHKATI NATION, INDIGENOUS BAR ASSOCIATION OF CANADA, WHITECAP DAKOTA FIRST NATION, GRAND COUNCIL OF THE CREES (EEYOU ISTCHEE) AND CREE NATION, GOVERNMENT, OKANAGAN NATION ALLIANCE, MOHAWK COUNCIL OF KAHNAWÀ:KE, ASSEMBLY OF FIRST NATIONS, MÉTIS NATIONAL COUNCIL AND MANITOBA MÉTIS FEDERATION INC., NUCHATLAHT FIRST NATION, CONGRESS OF ABORIGINAL PEOPLES, LUMMI NATION, and MÉTIS NATION BRITISH COLUMBIA INTERVENERS REPLY FACTUM OF THE RESPONDENT, RICHARD LEE DESAUTEL, TO INTERVENERS’ FACTUMS (Pursuant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada and Order of Cȏté J. made June 30, 2020) Arvay Finlay LLP Gowling WLG (Canada) LLP 1512 – 808 Nelson Street 160 Elgin Street, Suite 2600 Box 12149, Nelson Square Ottawa ON K1P 1C3 Vancouver BC V6Z 2H2 Tel: 613.786.0171 / Fax: 613.788.3587 Tel: 604.696.9828 Email: [email protected] Fax: 1.888.575.3281 Jeffrey W. Beedell Email: [email protected] Ottawa Agent for Counsel for the [email protected] Respondent, Richard Lee Desautel Mark G. Underhill and Kate R. Phipps Counsel for the Respondent, Richard Lee Desautel Attorney General of British Columbia Borden Ladner Gervais LLP Legal Services Branch 1300 – 100 Queen Street 1405 Douglas Street, 3rd Floor Ottawa ON K1P 1J9 Victoria BC V8W 2G2 Tel: 613.369.4795 Tel: 250.387.0417 Fax: 613.230.8842 Fax: 250.387.0343 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Karen Perron Glen R. -

Canada's Ancient and Modern Constitution

1 University of British Columbia Law 353-001 Aboriginal and Treaty Rights Aboriginal Title Litigation David Rosenberg, QC Outline for Guest Lecture by Jack Woodward, QC March 6, 2019 Canada’s Ancient and Modern Constitution: Tribalism and Reconciliation Introduction: Tribalism Why do we have international borders? The late Justice Alvin Rosenberg, formerly of the Ontario Divisional Court, once said: “All international borders should be abolished.” He said that the very concept of international borders was not defensible morally. The central ideas of liberalism: that all people have equal dignity, equal worth, and equal rights, leads ultimately to the idea that boundaries between states have no legitimacy. But states exist, and they exist because human beings are tribal. Tribalism. The central problem that every constitution tries to solve is the problem of tribalism. What is the boundary of the state? What is the scope of state power over people in different parts of the state, and different people within the state? What are the rights of the rulers and the ruled? Those questions are about nationality, citizenship, sovereignty of distinct peoples, political, economic and property rights based on birth, identity, inheritance, language, shared history1, and race. All those questions are infused with the concept of us versus them. No matter how big or small is the state, there will be 1 [470] I conclude that the proper rights holder, whether for Aboriginal title or Aboriginal rights, is the community of Tsilhqot’in people. Tsilhqot’in people were the historic community of people sharing language, customs, traditions, historical experience, territory and resources at the time of first contact and at sovereignty assertion. -

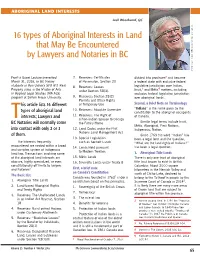

16 Types of Aboriginal Interests in Land

ABORIGINAL LAND INTERESTS Jack Woodward, QC 16 types of Aboriginal Interests in Land that May Be Encountered by Lawyers and Notaries in BC Photo credit: Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs Columbia Indian of British Union credit: Photo From a Guest Lecture presented 7. Reserves: Certificates divided into provinces2 and became March 31, 2016, to BC Notary of Possession, Section 20 a federal state with exclusive federal students in Ron Usher’s SFU 611 Real 8. Reserves: Leases legislative jurisdiction over Indian, 3 4 Property class in the Master of Arts under Section 58(3). Inuit, and Métis matters, including in Applied Legal Studies (MA ALS) exclusive federal legislative jurisdiction program at Simon Fraser University. 9. Reserves: Section 28(2) over aboriginal lands. Permits and Other Rights his article lists 16 different of Temporary Use Second, a Brief Note on Terminology 10. Reserves: Absolute Surrender “Indians” is the name given by the types of aboriginal land constitution to the aboriginal occupants interests; Lawyers and 11. Reserves: The Right of of Canada. T a Non-Indian Spouse to Occupy BC Notaries will normally come the Family Home Similar legal terms include Inuit, Métis, Aboriginal, First Nations, into contact with only 2 or 3 12. Land Codes under the First Indigenous, Native. Nations Land Management Act of them. Since 1763 the word “Indian” has 13. Special Legislation been a legal term and the question, The interests frequently such as Sechelt Lands “What are the land rights of Indians?” encountered are nested within a broad 14. Lands Held pursuant has been a legal question. -

Treaties and the Law

Treaties and the Law Information Backgrounder Office of the Treaty Commissioner Acknowledgements This publication was developed by the Office of the Treaty Commissioner (OTC) as part of its mandate to support a better understanding of the historic treaties between First Nations People and the Crown in what is now known as Saskatchewan. The purpose of this publication is to provide support to Law 30 teachers as they teach about treaties. This publication provides teachers, students and the general public with information about treaties and the law. The content of this publication is intended as general information only and should not form the basis of legal advice of any kind. Individuals seeking specific legal advice should consult a lawyer. The OTC gratefully acknowledges the funding provided by the Law Foundation of Saskatchewan for the development and printing of this publication. This publication was researched, written, and prepared by the Public Legal Education Association of Saskatchewan (PLEA) for the OTC. The OTC gratefully acknowledges the following organizations and individuals who provided valuable consultative support: • Saskatchewan Learning - Brent Toles, Social Sciences Consultant, • Federation of Saskatchewan Indians • Indian and Northern Affairs Canada • Tim McFadden - Thom Collegiate • Delise Fathers - Riverview Collegiate • Ken Boyd - Rosetown Central High • Patricia Fergusson - Estevan Comp. High • Randy Danyliw - Aden Bowman • Larry Mikulcik - William Derby School • Shannon Miller - Three Lakes School • Cheryl Cowan - Piyesiw Awasis • Kelly Brown - Carlton Comp High • Maria Sparvier - Cowesses School © 2007, David M. Arnot ISBN: X-XXXXXX-XX-X Contents may not be commercially reproduced, but any other reproduction is encouraged. Cover photos/illustrations credit Office of the Treaty Commissioner. -

Converting the Communal Aboriginal Interest Into Private Property Sarnia, Osoyoos, the Nisga’A Treaty and Other Recent Developments

Converting the Communal Aboriginal Interest into Private Property Sarnia, Osoyoos, the Nisga’a Treaty and Other Recent Developments JACK WOODWARD The Communal Aboriginal Interest in Aboriginal Title Delgamuukw1 makes it clear that aboriginal title—first described as a “personal and usufructuary right” 2 and more recently as a sui generis in- terest in land “best characterized by its general inalienability, coupled with the fact that the Crown is under an obligation to deal with the land on the Indian’s behalf when the interest in surrendered” 3—is a right to the land itself.4 Aboriginal title arises from First Nations’ possession of lands before the assertion of British sovereignty and crystallized into a burden on the underlying title of the Crown at the time of assertion of sovereignty.5 For the purposes of this paper, aboriginal title has the following important attributes: Notes will be found on pages 101–102. 93 94 Beyond the Nass Valley (1) Aboriginal title is a collective interest in land and not an individual right. It is a collective right to land held by all members of an ab- original nation. Decisions with respect to that land must be made by that community.6 (2) Aboriginal title lands cannot be transferred, sold or surrendered except to the Crown.7 (3) Aboriginal title is a right to the land itself.8 (4) Aboriginal title is a right to exclusive use and occupation.9 (5) Aboriginal title lands have an inherent limit—they cannot be used for purposes that are irreconcilable with the First Nations attach- ment to the land without surrender.10 (6) Unextinguished aboriginal title is constitutionally entrenched.11 The first attribute is important in determining who can make the deci- sion to modify aboriginal title. -

Draft BC Response Factum

Court of Appeal File No. CA035617 Supreme Court File No. 90 0913 Supreme Court Registry: Victoria COURT OF APPEAL ON APPEAL FROM: THE ORDER OF JUSTICE VICKERS OF THE SUPREME COURT OF BRITISH COLUMBIA PRONOUNCED NOVEMBER 20, 2007 BETWEEN: Roger William, on his own behalf and on behalf of all other members of the Xeni Gwet’in First Nations Government and on behalf of all other members of the Tsilhqot’in Nation Respondent (Plaintiff) AND: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of the Province of British Columbia, the Regional Manager of the Cariboo Forest Region Appellant (Defendant) AND: The Attorney General of Canada Respondent (Defendant) FACTUM OF THE RESPONDENT, ROGER WILLIAM , ON HIS OWN BEHALF AND ON BEHALF OF ALL OTHER MEMBERS OF THE XENI GWET'IN FIRST NATIONS GOVERNMENT AND ON BEHALF OF ALL OTHER MEMBERS OF THE TSILHQO’TIN NATION Roger William Her Majesty the Queen in Right of the David M. Rosenberg, Q.C. Province of British Columbia, the Rosenberg & Rosenberg Regional Manager of the Cariboo Forest 671D Market Hill Region Vancouver, BC V5Z 4B5 Patrick G. Foy, Q.C. Jack Woodward Kenneth J. Tyler Jay Nelson Borden Ladner Gervais LLP Woodward & Company Lawyers LLP 1200 Waterfront Centre 2nd Floor, 844 Courtney Street 200 Burrard Street Victoria, BC V8W 1C4 Vancouver, BC V7X 1T4 The Attorney General of Canada Brian McLaughlin Jennifer Chow Department of Justice Canada Aboriginal Law Section 900 – 840 Howe Street Vancouver, BC V6Z 2S9 INDEX CHRONOLOGY OF RELEVANT DATES IN LITIGATION ............................................ iv OPENING STATEMENT ............................................................................................... vii PART 1 – STATEMENT OF FACTS ............................................................................... 1 PART 2 – ISSUES ON APPEAL.................................................................................... -

REPLY FACTUM of the APPELLANT, HER MAJESTY the QUEEN (Pursuant to the Order Dated June 30, 2020)

SCC File No. 38734 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR BRITISH COLUMBIA) BETWEEN: HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Appellant (Appellant) -and- RICHARD LEE DESAUTEL Respondent (Respondent) -and- ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ONTARIO, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF QUEBEC, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE YUKON TERRITORY, ATTORNEY GENERAL FOR SASKATCHEWAN, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW BRUNSWICK, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ALBERTA, PESKOTOMUHKATI NATION, INDIGENOUS BAR ASSOCIATION IN CANADA, WHITECAP DAKOTA FIRST NATION, GRAND COUNCIL OF THE CREES (EEYOU ISTCHEE) AND CREE NATION GOVERNMENT, OKANAGAN NATION ALLIANCE, MOHAWK COUNCIL OF KAHNAWÀ:KE, ASSEMBLY OF FIRST NATIONS, MÉTIS NATIONAL COUNCIL AND MANITOBA METIS FEDERATION INC., NUCHATLAHT FIRST NATION, CONGRESS OF ABORIGINAL PEOPLES, LUMMI NATION AND MÉTIS NATION BRITISH COLUMBIA Interveners REPLY FACTUM OF THE APPELLANT, HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN (Pursuant to the Order dated June 30, 2020) Attorney General of British Columbia Borden Ladner Gervais LLP 3 - 1405 Douglas Street 1300 - 100 Queen Street Victoria, BC V8W 2G2 Ottawa, ON K1P 1J9 Glen R. Thompson Nadia Effendi Heather Cochran Tel: 613.787.3562 Tel: 250.387.0417 Fax: 613.230.8842 Fax: 250.387.0343 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Appellant, Ottawa Agents for the Appellant, Her Majesty the Queen Her Majesty the Queen 2 ORIGINAL TO: Registrar Supreme Court of Canada 301 Wellington Street Ottawa, ON K1A 0J1 COPY TO: Arvay Finlay LLP Gowling WLG (Canada) LLP 1512 - 808 Nelson Street 2600 - 160 Elgin Street Box 12149, Nelson Square Ottawa, ON K1P 1C3 Vancouver, BC V6Z 2H2 Mark G. -

Download Download

POLITICAL SCIENCE UNDERGRADUATE REVIEW VOL. 6 Winter 2021 Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution Act and Indigenous Self- Determination in Canada By Hailey Lothamer Abstract This research paper analyzes the impacts of Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution on the enhancement of Indigenous rights in Canadian politics. As outlined in Section 35, Indigenous rights are recognized as existing prior to the Constitution Act of 1982 and the identities of Aboriginal, Inuit and Métis peoples are defined. Academic literature, television broadcasts, and personal accounts of the implementation and effects of Section 35 were used to conduct this research and investigate the origins of this section in the Constitution. Notably, this analysis demonstrated that the inclusion of Section 35 in the Constitution has led to more public discussion and court cases to claim treaty rights by Indigenous peoples. The effect of including Indigenous rights in the Canadian Constitution has expanded the role of the courts in adjudicating relations between the Canadian government and Indigenous people, effectively expanding the accountability of the Canadian government to upholding treaty rights. Overall, the findings of this paper were that Section 35 plays a large role in promoting awareness of reconciliation to the Canadian public, however, it stops short of including Indigenous people as meaningful participants in their own self-determination. An Introduction to Section 35 Enshrined in the Canadian Constitution Act of 1982, Section 35 has played a critical role in transforming Crown-Indigenous relations in a manner that emphasizes the importance of Indigenous self-governance (Webber 2016, 66). Why was Section 35 of the Constitution Act created and how does it reaffirm the rights of Indigenous people in Canada? Section 35 of the Constitution Act was created to reflect the public consensus that Indigenous people possess some inherent rights.