Australian Humanities Review: Issue 48, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marilyn Monroe, Lived in the Rear Unit at 5258 Hermitage Avenue from April 1944 to the Summer of 1945

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2015-2179-HCM ENV-2015-2180-CE HEARING DATE: June 18, 2015 Location: 5258 N. Hermitage Avenue TIME: 10:30 AM Council District: 2 PLACE: City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: North Hollywood – Valley Village 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: South Valley Los Angeles, CA Neighborhood Council: Valley Village 90012 Legal Description: TR 9237, Block None, Lot 39 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the DOUGHERTY HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER(S): Hermitage Enterprises LLC c/o Joe Salem 20555 Superior Street Chatsworth, CA 91311 APPLICANT: Friends of Norma Jean 12234 Chandler Blvd. #7 Valley Village, CA 91607 Charles J. Fisher 140 S. Avenue 57 Highland Park, CA 90042 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. NOT take the property under consideration as a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10 because the application and accompanying photo documentation do not suggest the submittal warrants further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. MICHAEL J. LOGRANDE Director of Planning [SIGN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Shannon Ryan, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachments: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2015-2179-HCM 5258 N. Hermitage, Dougherty House Page 2 of 3 SUMMARY The corner property at 5258 Hermitage is comprised of two one-story buildings. -

Statistical Report on General Election, 2009 to the Legislative Assembly of Sikkim

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 2009 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF SIKKIM ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – State Elections, 2009 Legislative Assembly of Sikkim STATISTICAL REPORT CONTENTS SUBJECT PAGE No. Part-I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 2. Other Abbreviations And Description 2 3. Highlights 3 4. List of Successful Candidates 4 5. Performance of Political Parties 5 6. Candidate Data Summary 6 7. Electors Data Summary 7 8. Women Candidates 8 9. Constituency Data Summary 9 - 40 10. Detailed Results 41 - 48 Election Commission of India- State Election, 2009 to the Legislative Assembly Of Sikkim LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTY TYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 3 . INC Indian National Congress 4 . NCP Nationalist Congress Party STATE PARTIES 5 . SDF Sikkim Democratic Front REGISTERED(Unrecognised) PARTIES 6 . SGPP Sikkim Gorkha Prajatantric Party 7 . SHRP Sikkim Himali Rajya Parishad Party 8 . SJEP Sikkim Jan-Ekta Party INDEPENDENTS 9 . IND Independent Page 1 of 48 Election Commission of India, State Election,2009 to the legislative assembly of Sikkim OTHER ABBREVIATIONS AND DESCRIPTIONS ABBREVIATIONS DESCRIPTIONS FD Forfeited Deposits GEN General Constituency SC Reserved for Scheduled Castes BL Reserved for Bhutia Lepcha M Male F Female O Others T Total N National Party S State Party U Registered (Unrecognised) Party Z Independent Page 2 of 48 Election Commission of India- State Election, 2009 to the Legislative Assembly Of Sikkim HIGHLIGHTS 1. NO OF CONSTITUENCIES TYPE OF CONSTITUENCY GEN * SC BL TOTAL NO OF CONSTITUENCIES 18 2 12 32 Include Sangha Constituency = 1 2. -

SUPPLEMENTS 92373 01 1-240 R2mv.Qxd 7/24/10 12:06 AM Page 193

92373_01_1-240_r2mv.qxd 7/24/10 12:17 AM Page 225 SUPPLEMENTS 92373_01_1-240_r2mv.qxd 7/24/10 12:06 AM Page 193 Note: It is very likely that this letter was written at the beginning of 1956, during the filming of Joseph Logan’s Bus Stop, when Paula Strasberg worked as Marilyn’s coach for the first time. 92373_01_1-240_r2mv.qxd 7/24/10 1:16 AM Page 194 92373_01_1-240_r2mv.qxd 7/24/10 12:07 AM Page 195 Dear Lee & Paula, Dr. Kris has had me put into the New York Hospital—psychiatric division under the care of two idiot doctors—they both should not be my doctors. You haven’t heard from me because I’m locked up with all these poor nutty people. I’m sure to end up a nut if I stay in this nightmare—please help me Lee, this is the last place I should be—maybe if you called Dr. Kris and assured her of my sensitivity and that I must get back to class so I’ll be better prepared for “Rain.” Lee, I try to remember what you said once in class “that art goes far beyond science.” And the scary memories around me I’d like to forget—like screaming woman etc. Please help me—if Dr. Kris assures you I am all right—you can assure her I am not. I do not belong here! I love you both. Marilyn P.S. forgive the spelling—and there is nothing to write on here. I’m on the dangerous floor!! It’s like a cell can you imagine—cement blocks. -

Mariyn Monroe Release-NEW

September 2004 I Wanna Be Loved By You: Photographs of Marilyn Monroe from the Leon and Michaela Constantiner Collection on View at Brooklyn Museum November 12, 2004 Media Preview November 10, 2004, 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. Some 200 photographs of Marilyn Monroe by thirty-nine photographers will be on view at the Brooklyn Museum from November 12, 2004, through March 20, 2005, in the Robert E. Blum Gallery on the Museum’s first floor. Among the photographers whose work will be featured are Eve Arnold, Richard Avedon, Cecil Beaton, Cornell Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Andre De Dienes, Robert Frank, Milton Greene, Phillipe Halsman, Ben Ross, Bert Stern, Weegee, Gary Winogrand, and George Zimbel. I Wanna Be Loved By You: Photographs of Marilyn Monroe from the Leon and Michaela Constantiner Collection will present photographic portraits dating from 1945, when Marilyn (then Norma Jeane Baker) was 19 years old, to images taken just a few weeks before her death in 1962 at the age of 36. The collection, which can be viewed as a virtual who’s who of photographers of the postwar period (1950–60), includes a unique series of fifty-nine images shot by Bert Stern in 1962, titled “The Last Sitting.” Behind-the-scenes photo- graphs, pictures that capture private moments, and documentary footage of Marilyn during many periods of her career will also be featured. Leon and Michaela Constantiner’s extensive collection, which has been amassed by Mr. Constantiner, focuses on no particular collecting style or photographer. Instead, it is based on his love for Marilyn and an apprecia- tion of her beauty, talent, and sensitivity. -

Marilyn Monroe's Star Canon: Postwar American Culture and the Semiotics

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--English English 2016 MARILYN MONROE’S STAR CANON: POSTWAR AMERICAN CULTURE AND THE SEMIOTICS OF STARDOM Amanda Konkle University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.038 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Konkle, Amanda, "MARILYN MONROE’S STAR CANON: POSTWAR AMERICAN CULTURE AND THE SEMIOTICS OF STARDOM" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--English. 28. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/english_etds/28 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--English by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Public Catalog

7/24/2018 WebVoyage Record View 1 Public Catalog Copyright Catalog (1978 to present) Search Request: Left Anchored Title = Last Sitting Search Results: Displaying 1 of 2 entries The Last Sitting: a Series of Two-Thousand-and-Five-Hundred-and-Seventy-One... Type of Work: Visual Material Registration Number / Date: VA0001923509 / 2013-11-26 Application Title: The Last Sitting: a Series of Two-Thousand-and-Five-Hundred-and-Seventy-One Photographs Featuring Marilyn Monroe and Contained within the Copyrighted Work Entitled "Marilyn Monroe The Complete Last Sitting" Published in 1992 in the United Kingdom by Schirmer Art Books, an Imprint of Schirmer/Mosel Verlag GmbH, Munich. Title: The Last Sitting: a Series of Two-Thousand-and-Five-Hundred-and-Seventy-One Photographs Featuring Marilyn Monroe and Contained within the Copyrighted Work Entitled "Marilyn Monroe The Complete Last Sitting" Published in 1992 in the United Kingdom by Schirmer Art Books, an Imprint of Schirmer/Mosel Verlag GmbH, Munich. Description: Book, 463 p. Copyright Claimant: Estate of Bert Stern, Transfer: By inheritance. Address: 7915 1/8 Norton Avenue, West Hollywood, CA, 90046, United States. Date of Creation: 1962 Date of Publication: 1992-07-01 Nation of First Publication: United Kingdom Authorship on Application: Bert Stern, 1929-2013; Domicile: United States; Citizenship: United States. Authorship: photograph(s) Rights and Permissions: Paul E. Thomas, 200 South Sixth Street, Fredrikson & Byron, Suite 4000, Minneapolis, MN, 55402-1425, (612) 492-7365, [email protected] -

No Show by Kabi-Tingda Cong Candidate

24 April, 2004; NOW! 1 SBICAR Bharat Sanchar LOAN Saturday, 24 April, 2004 Vol. 3 No. 26 Gangtok Rs. 3 Nigam Ltd. the most convenient option Sanction and disbursement NOTICE It is notified that Telephone in One day Adalat will be held on 28/05/ Lowest interest at 9% 04 at 11 A.M. in the cham- ber of General Manager, No prepayment Telecom, Gtk. The Sub- No processing charge scribers are requested to kindly file their complaints Loan up to 90% regarding (1) excess billing Free accident insurance (2) Service (3) Non-provi- Repayment up to 84 months sion of New Telephone due to various reasons etc. by contact PT Bhutia 98320 35786 20/05/04 addressed to the or Chettri 94340 12824 AO (TR) O/o the GMT/GTK NO SHOW BY KABI-TINGDA CONG CANDIDATE a NOW REPORT SDF ARE ONE UP EVEN BEFORE ELECTIONS, GANGTOK, 23 April: On the fi- nal day of filing nominations, there was early jubilation in the SDF PALDEN “FAILS” TO FILE NOMINATIONS camp, utter confusion in the Cong date for filing nominations. SDF is ing for the formal announcements. [I] office and general dejection already one up without even the “We had no doubts that our can- among the Kabi-Tingda youth. The scrutiny and withdrawal of the WE DESERVED IT, SAYS KAZI didate, TT Bhutia would win, but much-promoted Cong [I] candidate nominations process being over. we had never expected that he from Kabi-Tingda in north Sikkim, Mr. Bhutia, if he had contested, SUPPORTERS CONVINCED would win uncontested,” he said. -

Chapter- Vi Political Organizations and the Issue of Ethnic Identity: Role of Political Parties & Ethnic Organizations

293 CHAPTER- VI POLITICAL ORGANIZATIONS AND THE ISSUE OF ETHNIC IDENTITY: ROLE OF POLITICAL PARTIES & ETHNIC ORGANIZATIONS. It is an acknowledged fact that political parties and organizations often tend to be ethnically oriented in terms of their membership, goals and support base, in an ethnically divided society or in societies where ethnic cleavages play a significant role in determining social relations. Parties and organizations in their tum may enhance the possibilities of ethnic divisions and conflicts. In a parliamentary democracy or a democratic polity which is ethnically divided, chances of emergence of ethnic political parties and organizations are greater for the simple reason that democratic institutions allow and facilitate such ethnic mobilization in the form of a party or organization. On the other hand, ethnic groups also may find it convenient to organize themselves around the political party or organization because it will assist ethnic groups to permeate democratic institutions and thereby to influence the decision-making process. Interestingly, ethnically based parties are in a sense incompatible or inconsistent with the image and meaning of a political party. Political parties as modem institutions are expected to convert exclusive and segmental interest into public interest. The political party appeals to common interests or attempts to create a combination of interests. Horowitz remarks that very concept of party is challenged by a political party, which is ascriptive and exclusive.1 In this sense ethnically based party or an ethnic party is a misnomer. Gabriel Almond has pointed out that 'particularistic parties' like the ethnic party are more like pressure groups. 2 In India, however, exclusivist ethnically oriented parties like Akali Dal, Asom Ghana Parishad etc. -

An Online Investigation Into the Death of Marilyn Monroe Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE DD GROUP: AN ONLINE INVESTIGATION INTO THE DEATH OF MARILYN MONROE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Professor David Marshall | 509 pages | 31 Mar 2005 | iUniverse | 9780595345205 | English | Bloomington IN, United States The DD Group: An Online Investigation Into the Death of Marilyn Monroe PDF Book Peter Lawford and the Ever Changing Story. Having been a HUGE Marilyn Monroe fan for many years, I have read and have re-read the most outrageous stories concerning her sad demise. Want to Read saving…. Happily smiling, rather than seductively smoldering, she is poised on the brink of becoming Marilyn. A primer on her life feels necessary before digging into this one. No Comments 0. Marilyn Monroe presents a series of problems, and this book is an attempt, if not to solve those problems, at least to explain them. Eventually it left even Plath behind. Many feminists view Marilyn with weariness, contempt or overt hostility. The story of Marilyn Monroe begins with the close unconscious association between dread and love, sex and death, that was so important to Freud; it ends having been translated into the conscious, resolved into the literal, turned into what we can see, what we can face, what we want to know. Stacey rated it it was amazing Aug 06, The photograph of Marilyn with a veil in her teeth is no truer than the picture of Marilyn in a white dress on a subway grating, or doing her makeup in a backstage mirror, or a candid shot of Marilyn laughing on her sofa. Why not assume that Marilyn Monroe opens the entire problem of biography? Although Marilyn Monroe was one of the most famous, most photographed, most written-about people in the twentieth century, we know less about her for certain than about many far more distant historical figures. -

29 March Page 3

Imphal Times Supplementary issue Page 3 150 candidates in fray for 32 Church not aligned with any Assembly seats in state political party: NEIRBC. Agency April 11, they said. Sikkim Chief Minister Gangtok (BL) and Tumen Agency Regional Bishop’s the growing concerns in underprivileged, Gangtok March 29, Two candidates Ratan Pawan Kumar Chamling, Lingi (B-L) seats in East and Itanagar March 29, Council (NEIRBC), who the country, like the promoting probity in Singh Rai (Sikkim HSP working president South Sikkim had called upon huge gap between the public life, ensuring a Altogether 150 Republican Party) and Bhaichung Bhutia and respectively.The 11 A statement was issued everyone to exercise rich and the poor, the safe environment for all, candidates are in fray for Nirmal Kumar Pradhan Chamling”s younger candidates in the fray for the by the Catholic leaders their franchise. meager wages for the safeguarding the rights 32 Assembly seats in (Independent) withdrew brother Rup Narayan lone Lok Sabha seat in of Northeast India “Voting at every election unorganized laborers, of the tribals over their Sikkim after three their names from Namchi- Chamling are among Sikkim are Dhiraj Kumar Rai saying that the church is a sacred duty and farmers’ distress, and land, water and forests, nominees withdrew their Singhithang assembly prominent candidates in (SRP), D B Katwal (SDF), does not identify itself obligation of every corruption at all levels. promoting communal candidature on constituency, while fray in the assembly Mahendra Thapa with political party. citizen,” the letter said, Rev Jala also issued a harmony and the spirit of Thursday, the last date another candidate Dal polls.Chamling, the ruling (Independent) Biraj Adhikari The letter was and urged everyone to seven-point guideline to national integrity for withdrawal, Election Bahadur Karki Sikkim Democratic Front (HSP), Bharat Basnett (INC), addressed to the rise above religion, church leaders, which through inter-religious officials said. -

THE BIHARI FLAVOUR in GANGTOK28 March, 2004; NOW! 1 DETAILS on Pg 6 Summer Collection Sunday, 28 March, 2004 Vol

THE BIHARI FLAVOUR IN GANGTOK28 March, 2004; NOW! 1 DETAILS ON pg 6 Summer Collection Sunday, 28 March, 2004 Vol. 3 No. 01 Gangtok Rs. 3 Air-Conditioned Slippers, sandals & formal/ casual shoes Grocery Shop for Men for Provisional Goods, Dry Flora sandals, Fruits & All Hotel Requirements (for kitchen) flat slippers WHOLE-SALES for ladies RETAIL-SALES at at the most reasonable prices Rajdeep the shoe shoppe Spectrum Color Lab Building, Near Amar/ Chaman Garage, Sevoke Road, Siliguri MG Marg, Gangtok. ph: 228865 ph: 2640799, 2640599 GREEN SIGNAL FROM LAL KOTHI Sikkim GNLF seeks Cong alliance, wants border constituencies SIKKIM REQUISITIONS 5 GNLF (S) SAYS NO TO COMPANIES OF CRPF FOR POLL DARJ-SIKKIM MERGER DUTY round of talks with the SPCC [I] RANJIT SINGH president Nar Bahadur Bhandari TURN TO pg4 GANGTOK, 27 March: The in this regard. GNLF’s Sikkim unit is keen on When pressed further on what The President of the GNLF (S), Satish Rai, 2nd from left, at the press conference. contesting the Assembly elections seat-sharing arrangement the party IXth Regional in May and seeking to strike an al- has in mind, Mr. Rai said, “Though test from the border constituencies Rai said the GNLF [S] had re- liance with the Congress [I] to ideally we would like to contest since those are the areas where we ceived the green signal from Lal present a joint opposition to the from at least 18 constituencies, we have most of our supporters.” Kothi to broach negotiations Language Day ruling Sikkim Democratic Front’s could settle for 12-13 seats provided When asked whether the with the Congress. -

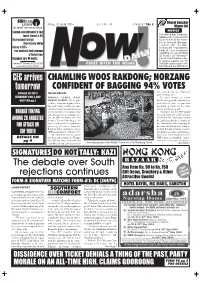

HONG KONG BAZAAR the Debate Over South Any Item Rs

30 April, 2004; NOW! 1 SBICAR Bharat Sanchar LOAN Friday, 30 April, 2004 Vol. 3 No. 32 Gangtok Rs. 3 the most convenient option Nigam Ltd. Sanction and disbursement in 1 day NOTICE It is notified that Telephone Lowest interest at 9% Adalat will be held on 28/05/ No prepayment charges 04 at 11 A.M. in the cham- No processing charge ber of General Manager, Telecom, Gtk. The Sub- Loan up to 90% scribers are requested to Free accidental death insurance kindly file their complaints regarding (1) excess billing of the borrower (2) Service (3) Non-provi- Repayment up to 84 months sion of New Telephone due to various reasons etc. by contact PT Bhutia 98320 35786 20/05/04 addressed to the or Chettri 94340 12824 AO (TR) O/o the GMT/GTK CEC arrives CHAMLING WOOS RAKDONG; NORZANG tomorrow CONFIDENT OF BAGGING 94% VOTES not denied any development ANAND OBEROI DETAILS OF CEC’S projects to the area.” ITINERARY FOR 3-DAY MIDDLE TUMIN, EAST He also wondered aloud VISIT ON pg 3 SIKKIM, 29 APRIL: “We are gath- whether the party the constituency ered here today not to gather votes, picked in the past elections had but to ask you to evaluate for your- anything to show for the trust self which party has worked for your shown in it by the people. BHARAT TENZING interest and which has ignored you Confident that the SDF would and cast your vote accordingly,” be- sweep the polls with all the 32 seats gan the SDF president and chief in its kitty, Mr.