William G Bainbridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Context for Department of Defense Facilities World War Ii Permanent Construction

DEPARTMeNT OF DEFENSE FACILITIES- WORLD WAR II PERMANENT CONSTRUhttp://aee-www.apgea.army.mil:8080/prod/usaee!eqlconserv/ww2pel.htm ~ - Delivery Order 21 Contract No. DACW31-89-D-0059 US Army Corps of Engineers-Baltimore District HISTORIC CONTEXT FOR DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE FACILITIES WORLD WAR II PERMANENT CONSTRUCTION May 1997 R. Christopher Goodwin and Associates, Inc. 241 E. Fourth Street Suite 100 Frederick, Maryland 21701 FINAL REPORT June 1997 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Historic Context for Department of Defense (DoD) World War H Permanent Construction combines two previous reports: Historic Context for Department of Defense Facilities World War H Permanent Construction (Hirrel et al., draft June 1994) and Methodology for World War H Permanent Construction (Whelan, draft August 1996). This project was designed to meet the following objectives: • To analyze and synthesize historical data on the military's permanent construction program during World War H. • To assist DoD cultural resource managers and other DoD personnel with fulfilling their responsibilities under the National Historic Preservation Act (NHP A) of 1966, as amended. Section 110 of the NHPA requires federal agencies to identity, evaluate, and nominate to the National Register of Historic Places historic properties under their jurisdiction. Section 110 Guidelines, developed by the National Park Service, U.S. Department ofthe Interior, direct federal agencies to establish historic contexts to identifY and evaluate historic properties (53FR 4727-46). • To develop a consistent historic context framework that provides comparative data and background information in a cost-effective manner, which will allow DoD personnel to assess the relative significance of World War II military construction. -

Delong Pier Tests at Fort Eustis, Virginia

TA .7 .W34 n o.3- 4 5 0 DELONG PIER TESTS AT FORT EUSTIS, VIRGINIA TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 3.450 February 1957 U. S. Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station CORPS OF ENGINEERS Vicksburg, Mississippi ARMY.MNC VICKSBUR. MIS. iii PREFACE The Waterways Experiment Station was requested by the Philadelphia District, CE, on 28 January 1955, to make soils foundation investigations and analyses of two sites on the James River at Fort Eustis, Virginia, where an Engineer Test Unit from the Engineer Center, CE, U. S. Army, planned to install a DeLong pier tramway system for use by the Transporta- tion Research and Development Command, Transportation Corps, U. S. Army, for conducting offshore cargo-discharge exercises. The Office, Chief of Engineers, had previously assigned primary responsibility for coordinating all phases of the tests to the Philadelphia District. Basic responsibility for installation of the tramway system, operational tests, and for the foundation tests and analyses were assigned, respectively, to the Engineer Center, Fort Belvoir, Virginia, the Trans- portation Research and Development Command (TRADCOM), Fort Eustis, Virginia, and the Waterways Experiment Station (WES), Vicksburg, Mississippi. The soils investigations were conducted in February, March, and April 1955 by personnel of WES assisted by military personnel of TRADCOM. TRADCOM furnished the floating plant required for the offshore work and personnel to assist WES personnel in the field exploration. Personnel of the Soils Division, Waterways Experiment Station, connected with the investigation were Messrs. W. J. Turnbull, W. G. Shockley, C. I. Mansur, T. B. Goode, and A. L. Mathews. This report was prepared by Mr. -

World War II Participants and Contemporaries: Papers

World War II Participants and Contemporaries: Papers Container List ACCETTA, DOMINICK Residence: Fort Lee, New Jersey Service: 355th Inf Regt, Europe Volume: -1" Papers (1)(2) [record of Cannon Co., 355th Inf. Regt., 89th Inf. Div., Jan.-July 1945; Ohrdruf Concentration Camp; clippings; maps; booklet ”The Story of the 89th Infantry Division;” orders; song; ship’s newspaper, Jan. 1946;map with route of 89th Div.] AENCHBACHER, A.E. "Gene" Residence: Wichita, Kansas Service: Pilot, 97th Bomber Group, Europe; flew DDE from Gibraltar to North Africa, November 1942 Volume: -1" Papers [letters; clippings] ALFORD, MARTIN Residence: Abilene, Kansas Service: 5th Inf Div, Europe Volume: -1" Papers [copy of unit newspaper for 5th Inf. Div., May 8, 1945; program for memorial service; statistics on service and casualties in wars and conflicts] ALLMON, WILLIAM B. Residence: Jefferson City, Missouri Service: historian Volume: -1” 104 Inf Div (1) (2) [after action report for November 1944, describing activities of division in southwest Holland; this is a copy of the original report at the National Archives] 1 AMERICAN LEGION NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS Residence: Indianapolis, Indiana Service: Veteran's organization Volume: 13" After the War 1943-45 [a monthly bulletin published by the Institute on Postwar Reconstruction, Aug. 1943-April 1945] American Legion Publications (1)-(11) [civil defense; rights and benefits of veterans; home front; citizenship; universal draft; national defense and security program; Americanism; employment manual; Boy Scouts-youth program; G. I. Bill of Rights; peace and foreign relations; disaster; natural resources; law and order; UMT-universal military training; national defense; veterans’ employment; 1946 survey of veterans; reprint of two pages from The National Legionnaire, June 1940; instructors manual for military drill; United Nations; junior baseball program] Army-Navy YMCA Bulletin, 1942-44 Atlas of World Battle Fronts [1943-45] China at War, 1939 [four issues published by the China Information Publishing Co.] Clippings [submarine war; Alaska; U.S. -

Evaluation of the Performance of the Xm759 Logistical Carrier

TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 3-808 EVALUATION OF THE PERFORMANCE OF THE XM759 LOGISTICAL CARRIER B. 6. Schreiner A A Rula January 196& Sponsored by U. S. Army Materiel Command Conducted by u. S. Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station CORPS OF ENGINEERS Vicksburg, Mississippi This document is subject to special export controls and each transmittal to foreign governments or foreign nationals may be made only with prior approval of U. S. Army Materiel Command. TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 3-808 j~y-,;v( J EVALUATION OF THE PERFORMANCE OF THE XM759 ~O~~S!~iL..~aBB.lg~j' by B. G. Schreiner A. A. Rula January 1968 Sponsored by " i U. S. Army Mat:eriel Command \ \ -",----: '- ~,,---- Conducted by U. S. Army Engineer Wat:erways Experiment: St:at:ion CORPS OF ENGINEERS )." . ,/ Vicksburg, Mississippi ARMY-MRC VICKSBURQ. MISS. rThis document is subject to special export controls and each transmittal to foreign governments or foreign nationals may be made only with prior approval of U. S. Army Materiel Command. THE CONTENTS OF THIS REPORT ARE NOT TO BE USED FOR ADVERTISING, PlffiLICATION, OR PROMOTIONAL PURPOSES. CITATION OF TRADE NAMES DOES NOT CONSTITUTE AN OFFICIAL EN DORSEMENT OR APPROVAL OF THE USE OF SUCH COMMERCIAL PRODUCTS. iii FOREWORD A development program for the XM759, 1-1/2-ton Logistical Carrier, Amphibious, was requested by the Commandant of the U. S. Marine Corps (USMC) in February 1965, and the U. S. Army Materiel Command (AMC) was designated as monitoring agency. AMC subsequently designated the U. S. Army-Tank Automotive Command (ATACOM) as the action agency. The study reported herein was a part of the development program and was conducted as a joint effort by ATACOM, the General Equipment Test Activity (GETA), and the U. -

PAPERS Container List Box 1: ACCETTA, DOMINICK Residence

WORLD WAR II PARTICIPANTS AND CONTEMPORARIES: PAPERS Container List Box 1: ACCETTA, DOMINICK Residence: Fort Lee, New Jersey Service: 355th Infantry Regiment, Europe Volume: -1" Papers (1) (2) [record of Cannon Co., 355th Infantry Regiment, 89th Infantry Division, January- July 1945; Ohrdruf Concentration Camp; clippings; maps; booklet ”The Story of the 89th Infantry Division;” orders; song; ship’s newspaper, January 1946; map with route of 89th Division] AENCHBACHER, A.E. "GENE" Residence: Wichita, Kansas Service: Pilot, 97th Bomber Group, Europe; flew DDE from Gibraltar to North Africa, November 1942 Volume: -1" Papers [letters and news clippings] ALFORD, MARTIN Residence: Abilene, Kansas Service: 5th Infantry Division, Europe Volume: -1" Papers [copy of unit newspaper for 5th Infantry Division, May 8, 1945; program for memorial service; statistics on service and casualties in wars and conflicts] ALLMON, WILLIAM B. Residence: Jefferson City, Missouri Service: historian Volume: -1” 104th Infantry Division (1) (2) [after action report for November 1944 describing activities of division in southwest Holland; this is a copy of the original report at the National Archives] AMERICAN LEGION NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS Residence: Indianapolis, Indiana Service: Veterans’ organization Volume: 13" 1 After the War 1943-1945 [a monthly bulletin published by the Institute on Postwar Reconstruction, August 1943-April 1945] Box 2: American Legion Publications (8)-(11) [civil defense; rights and benefits of veterans; home front; citizenship; universal draft; -

The Wars of Our Generation Tthe Wwars of Oour Ggeneration

THE WARS OF OUR GENERATION TTHE WWARS OF OOUR GGENERATION BY MEMBERS OF THE SENIOR MEN’S CLUB OF BIRMINGHAM, MICHIGAN WHO SERVED IN WORLD WAR II AND THE KOREAN WAR. 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS PROJECT CHAIRMAN: Chip Forbes EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Alvie Smith START-UP COMMITTEE: Tom Clapp, Chip Forbes, Dick Golze, Don Grant, Alvie Smith, Tom Van Voorhis EDITOR GROUP: Chairman, Dick Judy; Dick Davis, Al Fleming, Chip Forbes, Jack Harned, Harold Jackson, Bruce McCristal, Paul Pentecost, John Reddy, Alvie Smith PHOTOS: John Dudash COVER DESIGN: Jim Crabb COPY EDITING AND LAYOUT DESIGN: Lee Trumbull, The Community House MANUSCRIPT PREPARATION: Jim D’Allemand, Jerry Heller, Marvin Malik, Tom Shipley, Bill Sprague PROMOTION OF SALES: Co-Chairmen, John Reddy and Alvie Smith; Harold Jackson, Tom Van Voorhis SPECIAL THANKS: Dr. Jane Karolyn Vieth, who reviewed the prefaces to World War II and the Korean War, is a member of the History Department of Michigan State University. She teaches, gives seminars and has published articles on World War II. Baldwin Public Library provided valuable research on World War II and the Korean War. PRINTER: KTD Printing Associates, Madison Heights, Michigan Copyright © 2004 Senior Men’s Club of Birmingham All Rights Reserved DEDICATION The history of nations is scarred by many wars. When nations war, it is the young men and women in the “flower of their youth” who are called to do the fighting, and also to perform all of the support activities for military operations. The 1940s and early 1950s were the years of youth for members of the Senior Men’s Club of Birmingham who have contributed to this book. -

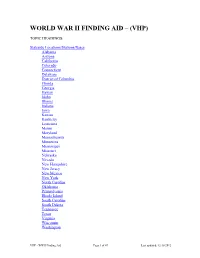

World War Ii Index

WORLD WAR II FINDING AID – (VHP) TOPIC HEADINGS: Stateside Locations/Stations/Bases Alabama Arizona California Colorado Connecticut Delaware District of Columbia Florida Georgia Hawaii Idaho Illinois Indiana Iowa Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maine Maryland Massachusetts Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Nebraska Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina Oklahoma Pennsylvania Rhode Island South Carolina South Dakota Tennessee Texas Virginia Wisconsin Washington VHP - WWII Finding Aid Page 1 of 49 Last updated: 12/18/2012 ETO Locations/Stations/Bases Austria Belgium England France Germany Holland Ireland Luxemburg Russia Wales MTO Locations/Stations/Bases Mediterranean North Africa Algeria Corsica Egypt Tunisia Greece Italy Sicily PTO Locations/Stations/Bases CBI Locations/Stations/Bases Other Locations/Stations/Bases (none of the above) Units Army Army Air Corps Marines Navy Coast Guard Merchant Marine Type of Duty Atomic Bombs Chaplains Combat (Special Interest – see also Battles) Limited Service Mechanical & Maintenance VHP - WWII Finding Aid Page 2 of 49 Last updated: 12/18/2012 Medical Military Intelligence/Reconnaissance Occupation - Italy Occupation – Germany Occupation - Japan Supply & Logistics Training Transport Other Duty Battles Prisoner of War Concentration Camps - liberators or other encounters Civilian Activities Homefront, Manufacturing and Industry Aircraft Industry Broadcasting Communications Industry Shipbuilding Industry Steel Industry Civilian Workers for the Military General Homefront Life (incl. Childhood) Red Cross Salvation Army Civil Defense YMCA, YWCA Other STATESIDE LOCATIONS/STATIONS/BASES STATESIDE Alexander, Ben Cooper Alexander, Wilson Carrington Adwell, Charles Edward “Pokey” Adwell, Lawrence N. Barnes, Thomas Marshall Berg, Robert K. Brake, Sophie Buckspan, Betty Jane Chumney, Ewing L. Clunan, Charles VHP - WWII Finding Aid Page 3 of 49 Last updated: 12/18/2012 Dalton-McMahon, Dorothy Dodson, Melvin C. -

1204 Public Law 91.511-Oct. 26. 1970 [84 Stat

1204 PUBLIC LAW 91.511-OCT. 26. 1970 [84 STAT. sentatives shall be transferred to the Office established under this subtitle; and, effective upon the date of enactment of this Act, the 40 Stat. 1141 i provisions of section 1303 of the Kevenue Act of 1918 shall have no 43 Stat. 353. 2 use 271. further applicability of any kind to the Speaker or to any committee, officer, employee, or property of the House of Representatives. TITLE VI—EFFECTIVE DATES EFFECTIVE DATES SEC. 601. The foregoing provisions of this Act shall take effect as follows: (1) Title I, title II (except part 2 thereof^, title III (except section 203 (d) (2), (d) (3), and (i) of the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, as amended by section 321 of this Act, and section 105 (e) and (f) of the Legislative Branch Appropriation Act, 1968', as amended by sec Ante, pp. 1143, tion 305 of this Act), and title IV, of this Act shall become effective 1167, 1175,1187. immediately prior to noon on January 3, 1971. Ante, p. 1169. (2) Part 2 of title II shall be effective with respect to fiscal years beginning on or after July 1, 1972. (3) Section 203(d) (2) and (3) of the Legislative Reorganization Ante, p. 1181. Act of 1946, as amended by section 321 of this Act, shall become effec tive at the close of the first session of the Ninety-second Congress. (4) Section 203 (i) of the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, as amended by section 321 of this Act, shall be effective with respect to fiscal years beginning on or after July 1,1970. -

![(WWII 5) [World War II]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3167/wwii-5-world-war-ii-11153167.webp)

(WWII 5) [World War II]

Military Collection State Archives of North Carolina North Carolina Military Camps Publications (WWII 5) [World War II] Draft Finding Aid Collection Number: WWII 5 Title: North Carolina Military Camps Publications Dates: 1941-1946, undated Creator: U.S. Armed Forces; various individuals Abstract The North Carolina Military Camps Publications is comprised of various camp newsletters and publications in North Carolina and the United States during World War II. The bulk of the collection contains publications from North Carolina military installations during WWII. During WWII, North Carolina housed more than one-hundred Army, Navy, Marine and Coast Guard facilities. Military service individuals, while stationed in military camps in North Carolina, would send publications to family members, all on behalf of the North Carolina Department of Archives and History. The goal for these issues was to illustrate to North Carolinians after WWII what service individuals from their state were encountering at various military installations during the war. While many of these publications were created with the use of military supplies, the majority of the publications were created by the military personnel, for the military personnel. In addition to North Carolina installations, this collection contains various publications from camps in the United States and territories, as well as publications for several countries, during World War II. These national and international publications were sent by native North Carolinian’s, and most publications contain the name and unit of the individual who sent the item. The goal for these issues was to illustrate to North Carolinians after WWII what service individuals from their state were encountering at various military installations during the war. -

Cyclops 1943

3 0642 00 52 8036 iiii';> .r\»v REF U 428 C9 1943 CYCLOPS Library Bureau J.U..^' ^// JI->JA sif w ^th '^COLU., ,,,,,, Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation la http://www.archive.org/details/cyclops194337nort ''To such a task tve dedicate our lives, our fortunes, everything that tve are and everything that Th^ tve have, tvith the pride of those tvho knotv that the day has come tvhen America is privileged to spend her blood and her might for the principles that gave her birth and happiness and the peace tvhich she has treasured. God helping her, she can do no other.'" Woodrotv Wilson. "Then we sailed onward, stricken at heart. And we came to the land of the Cyclopes, a forward and a lawless folk, who, trusting to deathless gods, plant not aught with their hands, neither plow: but, behold, all these things spring for them in plenty, unsown and unfilled, wheat, and barley, and vines, which bear great clusters of the juice of the grape, and the rain of Zeus gives them increase. These have neither gatherings for council nor oracles of law, but they dwell in hollow caves on the crests of the high hills, and each one utters the law to his children and his wives, and they reck not one of another." ^ 4- ^ ^ "The An Essentially West Point Military of College Georgia" North Georgia College, Cyclops / J4599 THE STUDENTS OF COLLEGE AT MONUMENTS TO THE PROGRESS OF A GREAT EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION This 1943 CYCLOPS will take its place beside the annuals of the past years of North Georgia College.