Theo Wilson: Professionalism Through the Eyes of a “Nuclear Powered Pixie”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POLETTA LOUIS ’92 Martin Luther King Jr

ReflectionsA PUBLICATION OF THE SUNY ONEONTA ALUMNI ASSOCIATION SPRING 2020 POLETTA LOUIS ’92 Martin Luther King Jr. Day Keynote Speaker ALSO... Earth & Atmospheric Sciences and School of Economics & Business celebrate 50 Years ReflectionsVolume XLXIII Number 3 Spring 2020 FROM NETZER 301 RECENT DONATION 2 20 TO ALDEN ROOM FROM THE ALUMNI @REDDRAGONSPORTS 3 ASSOCIATION 23 COLLEGE FOUNDATION 4 ACROSS THE QUAD 25 UPDATES EARTH & ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCES 2020 ALUMNI AWARD 11 50TH ANNIVERSARY 27 WINNERS 14 MARK YOUR CALENDAR 15 ALUMNI IN BARCELONA SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS & BUSINESS BEYOND THE PILLARS 15 50TH ANNIVERSARY 30 BEHIND THE DOOR: A LOOK ALUMNI PROFILE: 18 AT EMILY PHELPS’ OFFICE 41 ROZ HEWSENIAN ’75 On the Cover: Poletta Louis ’92 connects Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil rights legacy to the continuing struggle for equality and justice in all facets of our society. Photo by Gerry Raymonda Reflections Vol. XLXIII Number 3 Spring 2020 MANAGING EDITOR Laura M. Lincoln EDITOR Adrienne Martini LEAD DESIGNER Jonah Roberts CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Adrienne Martini Geoffrey Hassard Benjamin Wendrow ’08 CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Gerry Raymonda Michael Forster Rothbart Reflections is published three times a year by the Division of College Advancement and is funded in part by the SUNY Oneonta Alumni Association through charitable gifts to the Fund for Oneonta. SUNY Oneonta Oneonta, NY 13820-4015 Postage paid at Oneonta, NY POSTMASTER Address service requested to: Reflections Office of Alumni Engagement Ravine Parkway Reconnect SUNY Oneonta Oneonta, NY 13820-4015 Follow the Alumni Association for news, events, contests, photos, and more. For links to all of our Reflections is printed social media sites, visit www.oneontaalumni.com on recylced paper. -

C3972 Wilson, Theo, Papers, 1914-1997 Page 2 Such Major Trials As the Pentagon Papers, Angela Davis, and Patty Hearst

C Wilson, Theo R. (1917-1997), Papers, 1914-1997 3972 9 linear feet, 2 linear feet on 4 rolls of microfilm, 1 video cassette, 1 audio cassette, 1 audio tape MICROFILM (Volumes only) This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. INTRODUCTION The papers of Theodore R. Wilson, trial reporter for the New York Daily News, consist of newspaper articles, trial notes, awards, correspondence, photographs, and miscellaneous items spanning her 60-year career as a reporter and writer. DONOR INFORMATION The Theo Wilson Papers were donated to the University of Missouri by her son, Delph R. Wilson, on 5 August 1997 (Accession No. 5734). Additional items were donated by Linda Deutsch during August 1999 (Accession No. 5816). The Wilson papers are part of the National Women and Media Collection. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Theodora Nadelstein, the youngest of 11 children, was born in Brooklyn, New York, on 22 May 1917. She was first published at age eight in a national magazine for her story on the family’s pet monkey. Subsequent poems, short stories, plays, and articles of hers were published and produced at Girls High School in Brooklyn, which she attended from 1930 to 1934. She enrolled at the University of Kentucky where she became a columnist and associate editor of the school newspaper, the Kentucky Kernel, despite never taking any journalism courses. She graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1937 at age 19 and immediately went to work at the Evansville Press in Indiana. At the Press she was quickly promoted to tri-state editor, writing and handling copy from Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois. -

Past, Present and Future: a Thai Community Newspaper Sukanya

The Asian Conference on Media and Mass Communication 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan Past, Present and future: A Thai Community Newspaper Sukanya Buranadechachai Burapha University, Thailand 0006 The Asian Conference on Media and Mass Communication 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract This study focuses on Thai newspapers in Los Angeles, regarding services and benefits offered to the Thai community, their individual characteristics, and challenges they have encountered. In-depth interviews were conducted among 7 Thai newspaper publishers. A focus group consisted of 15 Thai readers with varying ages. Although, having provided critical contributions to Thai community, research found that Thai newspapers in LA lacked professional newspaper organization and quality reporting regarding local issues. iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org 1 The Asian Conference on Media and Mass Communication 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan Introduction Background, importance and problem of the research; Funding was granted by Isra Amantagul Foundation, the Thai Journalist Association under the Asian Partnership Initiative of University of Wisconsin at Madison, having been funded properly, the researcher was eligible to research Thai communities in the United States of America to increase the knowledge and understanding of mass communication. While a visiting professor at in the United States, the researcher recognized that local newspapers play an important role in local development, for it publicizes all information and connects people among the community. The status and existence of community newspapers in Los Angeles was interesting, especially in the aspects of pattern, content, and organizational management. The existence of local newspapers are beneficial to both government and private organizations, readers within the community, and the newspapers in the community itself. -

Ex-Spouse Arrested in Killing of Woman

IN SPORTS: Crestwood’s Blanding to play in North-South All-Star game B1 LOCAL Group shows its appreciation to Shaw airmen TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 2017 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents A5 Ex-spouse Community enjoys Thanksgiving meal arrested after volunteers overcome obstacles in killing of woman Victim was reported missing hours before she was discovered in woods BY ADRIENNE SARVIS [email protected] The ex-husband of the 27-year- old woman whose body was found in a shallow grave in Manchester State Forest last week has been charged in her death. James Ginther, 26, of Beltline J. GINTHER Boulevard in Columbia, was ar- rested on Monday in Louisville, Kentucky, for allegedly kidnapping and killing Suzette Ginther. Suzette’s body was found in the state forest about 150 feet off Burnt Gin Road by a hunter at about 4 p.m. on Nov. 16 — a few S. GINTHER hours after she was reported SEE ARREST, PAGE A7 Attorney says mold at Morris causing illness BY BRUCE MILLS [email protected] The litigation attorney who filed a class-ac- tion suit on behalf of five current and former Morris College students against the college last week says the mold issues on the campus are “toxic” and that he wants the col- lege to step up and fix the prob- lems. Attorney John Harrell of Har- rell Law Firm, PA, in Charleston, made his comments Monday con- cerning the case after the lawsuit HARRELL was filed last week and the JIM HILLEY / THE SUMTER ITEM college was notified. -

MITCHELL SYROP Born 1953, Yonkers, New York Lives and Works

MITCHELL SYROP Born 1953, Yonkers, New York Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA EDUCATION 1978 MFA, California Institute of the Arts, Santa Clarita, CA 1975 BFA, Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 Niza Guy, Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles, USA The Same Mistake, Croy Nielsen, Berlin, GERMANY 2014 It is Better to Shine Than to Reflect, Midway Contemporary Arts, Minneapolis, USA Hidden, Midway Contemporary Arts, Minneapolis, USA Gallery 3001 and the Chapel gallery at USC Roski School of Fine Arts and Design, Los Angeles, USA 2012 Thomas Solomon Gallery, Los Angeles, USA 2011 WPA Gallery, Los Angeles, USA 2004 Rosamund Felsen Gallery, Los Angeles, USA 2001 Spokane Falls College, Spokane, USA 1998 The Same Mistake, Rosamund Felsen Gallery, Los Angeles, USA 1997 Galeria Oliva Arauna, Madrid, Spain 1996 Rosamund Felsen Gallery, Los Angeles, USA 1994 Why I Wish I Was Dead, Santa Monica Museum of Art, Santa Monica, USA 1993 Paralysis Agitans, Rosamund Felsen Gallery, Los Angeles, USA Galeria Oliva Arauna, Madrid, Spain Rosamund Felsen Gallery, Los Angeles, USA 1990 Galeria Oliva Arauna, Madrid, Spain Lieberman & Saul Gallery, New York, USA 1989 University Art Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Lieberman & Saul Gallery, New York, USA 1988 Kuhlenschmidt-Simon, Los Angeles, USA 1987 Matrix Gallery, University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley, USA 1986 Kuhlenschmidt-Simon, Los Angeles, USA 1984 Richard Kuhlenschmidt Gallery, Los Angeles, USA SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2016 Le Merite, Treize, Paris, France -

Football Media Guide 2010

Wofford College Digital Commons @ Wofford Media Guides Athletics Fall 2010 Football Media Guide 2010 Wofford College. Department of Athletics Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/mediaguides Recommended Citation Wofford College. Department of Athletics, "Football Media Guide 2010" (2010). Media Guides. 1. https://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/mediaguides/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at Digital Commons @ Wofford. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Guides by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Wofford. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TTHISHIS ISIS WOFFORDWOFFORD FFOOOOTTBALLBALL ...... SEVEN WINNING SEASONS IN LAST EIGHT YEARS 2003 AND 2007 SOCON CHAMPIONS 2003, 2007 AND 2008 NCAA FCS PLAYOFFS ONE OF THE TOP GRADUATION RATES IN THE NATION 2010 NCAA PLAYO Football WOFFORDWOFFORD Media Guide 1990 1991 2003 2007 2008 ff S COntEntS 2010 SCHEDULE Quick Facts ...............................................................................2 Sept. 4 at Ohio University 7:00 pm Media Information ............................................................... 3-4 2010 Outlook ...........................................................................5 Sept. 11 at Charleston Southern 1:30 pm Wofford College ................................................................... 6-8 Gibbs Stadium ..........................................................................9 Sept. 18 UNION (Ky.) 7:00 pm Richardson Building ...............................................................10 -

Stop Smoking Systems BOOK

Stop Smoking Systems A Division of Bridge2Life Consultants BOOK ONE Written by Debi D. Hall |2006 IMPORTANT REMINDER – PLEASE READ FIRST Stop Smoking Systems is Not a Substitute for Medical Advice: STOP SMOKING SYSTEMS IS NOT DESIGNED TO, AND DOES NOT, PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE. All content, including text, graphics, images, and information, available on or through this Web site (“Content”) are for general informational purposes only. The Content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. NEVER DISREGARD PROFESSIONAL MEDICAL ADVICE, OR DELAY IN SEEKING IT, BECAUSE OF SOMETHING YOU HAVE READ IN THIS PROGRAMMATERIAL. NEVER RELY ON INFORMATION CONTAINED IN ANY OF THESE BOOKS OR ANY EXERCISES IN THE WORKBOOK IN PLACE OF SEEKING PROFESSIONAL MEDICAL ADVICE. Computer Support Services Not Liable: IS NOT RESPONSIBLE OR LIABLE FOR ANY ADVICE, COURSE OF TREATMENT, DIAGNOSIS OR ANY OTHER INFORMATION, SERVICES OR PRODUCTS THAT YOU OBTAIN THROUGH THIS SITE. Confirm Information with Other Sources and Your Doctor: You are encouraged to confer with your doctor with regard to information contained on or through this information system. After reading articles or other Content from these books, you are encouraged to review the information carefully with your professional healthcare provider. Call Your Doctor or 911 in Case of Emergency: If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor or 911 immediately. DO NOT USE THIS READING MATERIAL OR THE SYSTEM FOR SMOKING CESSATION CONTAINED HEREIN FOR MEDICAL EMERGENCIES. No Endorsements: Stop Smoking Systems does not recommend or endorse any specific tests, products, procedures, opinions, physicians, clinics, or other information that may be mentioned or referenced in this material. -

Individual Users Can Select and Move Between Competing Outlets, and Search Them, Instantly

individual users can select and move between competing outlets, and search them, instantly. Second, Petitioners have ignored the host of national and local websites identified by Tribune in t each market, which include local, independent websites. 159 The Petitioners also have ignored the local “blog” sites that today readily provide news, information and analysis, or at least are available to do so. Instead, the Petitioners rely on their characterization of a visit to the first page of the local Yahoo! website in each market to demonstrate that the Internet is only “old media.” This is a vast oversimplification of the options for news and information on the Internet, as well as the manner in which one might search for information of local interest. In addition to the websites and blogs identified by Tribune for each market, all the Petitioners need to do is to learn how to search the Internet. For example, within the last year Tribune demonstrated that the Internet hosts numerous traditional and non-traditional websites that discuss issues the LA Times has been accused of dominating. Six months ago, a simple online search for stories related to the KindDrew Medical Center in Los Angeles, using a search engine like Google or Yahoo, made clear that even two years later, there were dozens of other sources of information about the Medical Center, including information on the reforms the Medical Center had undergone since an LA Times series in 2004. These sources included (1) The Los Angeles County Department of Health Services that administers the hospital;’60(2) alternative online newspapers like People’s Weekly World, BlackPressUSA.com, New America Media, LA Voice.org, the Daily Trojan, the Compton Bulletin, Los Angeles City Beat, the Claremont Institute, National Review Online, the I59 See, e.g., Hartford Cross-Ownership Waiver Request at 33-37. -

In This Issue

Spring Newsletter 2016 In This Issue Did You Overextend Yourself? Chair's Message "What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up Like a raisin in Up Next! the sun? ...Or does it explode?" ~Langston Hughes Real Talk Faculty Office Hours Welcome Class #9 Real Talk Leadership: Affiliated Placements Head & Heart Moves That Allow Us to Spring Into Action Get Social! In January, we speed into the New Year tackling Spotlights head on a long list of resolutions that are almost Staff News impossible to keep. Just about this time of the year -February to March- we realize we may have Recommended Reading overextended ourselves on the resolution front. Dr. Thyonne Our Supporters Sometimes this gets us down. We feel defeated. Gordon CEO, But hear this: It's okay to admit we might have put Beyond Story in too large an order to handle in our normal lives. AABLI alumna, Chair's Message Class #3 Once we accept that there's too much on our plates, it's time to reset our resolutions so that they work for us. Whatever resolutions we had, a sure-fire way to keep them is to put in place some tools that will accelerate our process. Top leaders use these five tools regularly to keep from overextending and to stay on track. Try them and let us know how they work for you. Read more... There is an oft repeated saying: "If you want to get a task completed, give it to someone who is busy." Faculty Office Hours: Finance There was a time that I believed that statement to be a universal truth. -

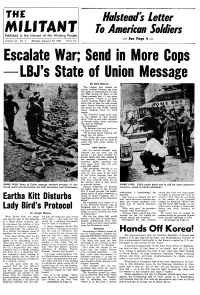

Send in More Cops LBJ's State of Union Message

UntalftHINIIIHIItHIIIIUtiiHitiiUIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIlllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllnllltlllllllfHHINftiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiUIIIIIIIIIIIHIItllllllllllllllltllllllllllllllfiiiiiiiiiUIIIIIIIIUtllfllllllllllllllllttulllllltllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll. THE Holsteotl's Letter MILITANT To Amerimn Soldiers Published in the Interest of the Working People -See Page 4- Volume 32 -No. 5 Monday, January 29, 1968 Price lOc llllllllllllllllllllllllfllllllllllll1iH11tlllllllllllltlllllllllllltlln.tiiiiiii11111111111111111111111U111111111111111111111111111111111111liiiUIIUIIUIIIIII!IUHUIIHII!IIIIIIIHHIIIII!Itlii!HIIIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIUIIIIIIIIUIIIIII!l!iUIIHHII11!11111111111111111111111111111111111111UI Escalate War; Send in More Cops LBJ's State of Union Message By Dick Roberts The longest and loudest ap plause Lyndon Johnson got from the gang of reactionaries on Cap itol Hill during his State of the Union message Jan. 17 was when he declared: "There is no more urgent business before this Con gress than to pass the safe streets acts." Every cheering racist pres ent knew he was really talking about cracking down on black people. The President spent more time on the subject of "law enforce ment" than on any other domestic or foreign policy issue, including the war in Vietnam. He promised: "To develop state and local mas ter plans to combat crime. "To provide better training and better pay for police. "To bring the most advanced technology to the war on crime in every city and every county in America." Only Answer For the second straight year, Johnson did not even pay lip service to the black struggle for human rights. His only answer to the demands expressed in last summer's ghetto uprisings was more guns, more cops, and even more FBI agents. One paragraph devoted to re· inforcing the FBI by 100 men took up more space in the State of the Union message than the plight of the nation's farmers, who have recently been hit by the sharpest drop in farm prices MORE WAR. -

The Rise and Demise of Confidential Magazine

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 25 (2016-2017) Issue 1 Article 4 October 2016 The Most Loved, Most Hated Magazine in America: The Rise and Demise of Confidential Magazine Samantha Barbas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Repository Citation Samantha Barbas, The Most Loved, Most Hated Magazine in America: The Rise and Demise of Confidential Magazine, 25 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 121 (2016), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmborj/vol25/iss1/4 Copyright c 2016 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj THE MOST LOVED, MOST HATED MAGAZINE IN AMERICA: THE RISE AND DEMISE OF CONFIDENTIAL MAGAZINE Samantha Barbas * INTRODUCTION Before the National Enquirer , People , and Gawker , there was Confidential . In the 1950s, Confidential was the founder of tabloid, celebrity journalism in the United States. With screaming headlines and bold, scandalous accusations of illicit sex, crime, and other misdeeds, Confidential destroyed celebrities’ reputations, relation- ships, and careers. Not a single major star of the time was spared the “Confidential treatment”: Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, Liberace, and Marlon Brando, among others, were exposed in the pages of the magazine. 1 Using hidden tape recorders, zoom lenses, and private investigators and prostitutes as “informants,” publisher Robert Harrison set out to destroy stars’ carefully constructed media images, and in so doing, built a media empire. Between 1955 and 1957, Confidential was the most popular, bestselling magazine in the nation. -

Nancy Buchanan Nancybuchanan.Net Curriculum Vitae 1969 BA, University of California, Irvine 1971 MFA, University of California

Nancy Buchanan nancybuchanan.net Curriculum Vitae 1969 BA, University of California, Irvine 1971 MFA, University of California, Irvine EXHIBITIONS/VIDEO SCREENINGS/MEDIA PRESENTATIONS 2020 Artists + Poets, http://suturo.com/artistsandpoems/index.php Show Me the Signs, Blum + Poe, Los Angeles, CA Virtual Talks with Media Activists, https://mediaburn.org/events/virtual-talks-with-video-activists/nancy-buchanan/ Digital Power, https://digital-power.siggraph.org/ ACM SIGGRAPH Do Not Link, http://www.upstream.gallery 2019 California Winter, Kristina Kite Gallery, Los Angeles, CA With a Little Help from My Friends — A Benefit for Bryan Chagolla, Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles These Creatures, Wignall Museum of Contemporary Art, Rancho Cucamunga, CA The Vision Board, Paul Kopeiken Gallery, Culver City, CA Book Launch — Hair Stories, POTTS, Alhambra, CA 2018 Functional – Small Ceramic Works, Future Studio Gallery, Los Angeles, CA Collecting on the Edge, Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University, Logan, Utah Remote Castration, LAXART, Los Angeles, CA Group video screening, Provisional Gallery, San Francisco, CA Tow Truck Towing a Tow Truck, as-is.la, Los Angeles, CA 2017 Pursuing the Unpredictable: The New Museum 1977 – 2017, New York, NY Faces: Gender, Art, Technology: 20 years of interactions, connections and collaborations, Schaumbad, Graz, Austria MFRU 2017 Computer Art, various locations, Maribor, Slovenia Consumption, Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles, CA (solo show) Nancy Buchanan, Morgan Canavan, Sidsel Meineche Hansen,