Overview Funding Document Vmay 2011 Protected

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tumen Triangle Documentation Project

THE TUMEN TRIANGLE DOCUMENTATION PROJECT SOURCING THE CHINESE-NORTH KOREAN BORDER Edited by CHRISTOPHER GREEN Issue Two February 2014 ABOUT SINO-NK Founded in December 2011 by a group of young academics committed to the study of Northeast Asia, Sino-NK focuses on the borderland world that lies somewhere between Pyongyang and Beijing. Using multiple languages and an array of disciplinary methodologies, Sino-NK provides a steady stream of China-DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea/North Korea) documentation and analysis covering the culture, history, economies and foreign relations of these complex states. Work published on Sino-NK has been cited in such standard journalistic outlets as The Economist, International Herald Tribune, and Wall Street Journal, and our analysts have been featured in a range of other publications. Ultimately, Sino-NK seeks to function as a bridge between the ubiquitous North Korea media discourse and a more specialized world, that of the academic and think tank debates that swirl around the DPRK and its immense neighbor. SINO-NK STAFF Editor-in-Chief ADAM CATHCART Co-Editor CHRISTOPHER GREEN Managing Editor STEVEN DENNEY Assistant Editors DARCIE DRAUDT MORGAN POTTS Coordinator ROGER CAVAZOS Director of Research ROBERT WINSTANLEY-CHESTERS Outreach Coordinator SHERRI TER MOLEN Research Coordinator SABINE VAN AMEIJDEN Media Coordinator MYCAL FORD Additional translations by Robert Lauler Designed by Darcie Draudt Copyright © Sino-NK 2014 SINO-NK PUBLICATIONS TTP Documentation Project ISSUE 1 April 2013 Document Dossiers DOSSIER NO. 1 Adam Cathcart, ed. “China and the North Korean Succession,” January 16, 2012. 78p. DOSSIER NO. 2 Adam Cathcart and Charles Kraus, “China’s ‘Measure of Reserve’ Toward Succession: Sino-North Korean Relations, 1983-1985,” February 2012. -

The Evening Gazette, Indiana, PA Korean War Weekly Front Pages

PMM BLOG ARCHIVE November 17, 2020 70 Years Later, the Korean War, The Evening Gazette, Indiana, PA Korean War Weekly Front Pages The First Week of November 1950 The Evening Gazette, Indiana, PA The Chinese Communists pause. General MacArthur formally notified the UN Security Council that Chinese Communist forces were fighting US troops in Korea. He said, “…the United Nations are presently in hostile contact with Chinese Communist military units deployed for action against the forces of the United command.” A high-ranking Eighth Army staff officer said the Chinese have probably 300,000 troops deployed along the Korean-Manchurian border.The situation in the critical Unsan-Kuna area, north of Pyongyang, appeared stabilized. In the northeast, two US Marine battalions were cut off north of Sudong, while other Marines, driving north toward the Changjin Reservoir, had met strong opposition. Near Majon, a third isolated battalion was reported dug in and in no danger. ROK Capital Division troops and Red Koreans were engaged in bitter street fighting in Kilchu in the northeast. As the week progressed, UN troops were pushing forward on all fronts amid an unexplained Communist withdrawal. A surprise news blackout had been clamped on developments between Communist battle lines and the Chinese border, but the Chinese appeared to be awaiting orders. Sixteen propeller-driven US F-51 Mustang fighters engaged ultramodern Russian-built jet fighters in the longest air battle of the Korean war. American F-80 Shooting Star jets, ordered to the battle over Sinuiju, near the border with China, arrived too late to engage. No American planes were damaged; three of the Mig-15 aircraft were reported hit, and all enemy planes fled across the border after the hour-and-a-half long dogfight. -

Pdf | 431.24 Kb

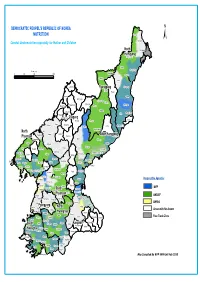

DEMOCRATIC PEOPEL'S REPUBLIC OF KOREA NUTRITION Onsong Kyongwon ± Combat Undernutrition especially for Mother and Children North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Musan Chongjin City Kilometers Taehongdan 050 100 200 Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Kanggye City Chagang Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Responsible Agencies Sunchon City Kowon Sukchon Sinyang Sudong WFP Pyongsong City South Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan UNICEF Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Kangso Sinpyong Popdong UNFPA PyongyangKangnam Thongchon Onchon Junghwa YonsanNorth Kosan Taean Sangwon Areas with No Access Nampo City Hwangju HwanghaeKoksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Free Trade Zone Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City Singye Changdo South Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Kangwon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Jaeryong HwanghaeSonghwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Kangryong Map Compiled By WFP VAM Unit Feb 2010. -

UN Consolidated Relief Appeal 2004

In Tribute In 2003 many United Nations, International Organisation, and Non-Governmental Organisation staff members died while helping people in several countries struck by crisis. Scores more were attacked and injured. Aid agency staff members were abducted. Some continue to be held against their will. In recognition of our colleagues’ commitment to humanitarian action and pledging to continue the work we began together We dedicate this year’s appeals to them. FOR ADDITIONAL COPIES, PLEASE CONTACT: UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS PALAIS DES NATIONS 8-14 AVENUE DE LA PAIX CH - 1211 GENEVA, SWITZERLAND TEL.: (41 22) 917.1972 FAX: (41 22) 917.0368 E-MAIL: [email protected] THIS DOCUMENT CAN ALSO BE FOUND ON HTTP://WWW.RELIEFWEB.INT/ UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, November 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................................11 Table I. Summary of Requirements – By Appealing Organisation ........................................................12 2. YEAR IN REVIEW ....................................................................................................................................13 2.1 CHANGES IN THE HUMANITARIAN SITUATION ...........................................................................................13 2.2 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW...........................................................................................................................14 2.3 MONITORING REPORT AND -

Electrifying North Korea: Governance Change, Vulnerability,And Environmental EAST-WEST CENTER WORKING PAPERS

EAST-WEST CENTER WORKING PAPERS Environmental Change, Vulnerability, and Governance No. 69, April 2014 Electrifying North Korea: Bringing Power to Underserved Marginal Populations in the DPRK Alex S. Forster WORKING WORKING PAPERS EAST-WEST CENTER WORKING PAPERS Environmental Change, Vulnerability, and Governance No. 69, April 2014 Electrifying North Korea: Bringing Power to Underserved Marginal Populations in the DPRK Alex S. Forster Alex S. Forster is a researcher on US-Asia relations at the East-West Center in Washington and a graduate student at the Elliott School East-West Center Working Papers is an unreviewed and of International Affairs, George Washington University. He will unedited prepublication series reporting on research in receive his Master’s degree with a dual concentration in East Asian progress. The views expressed are those of the author regional politics and security, and global energy security, in May and not necessarily those of the Center. East-West Center 2014. He holds a BA from Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Working Papers are circulated for comment and to inform OR, and spent more than four years working in South Korea as a interested colleagues about work in progress at the Center. consultant, translator, and teacher before beginning his graduate Working Papers are available online for free at studies. EastWestCenter.org/ewcworkingpapers. To order print copies ($3.00 each plus shipping and handling), contact the Center’s Publication Sales Office. A version of this policy proposal was prepared and submitted for a course on environmental security at the Elliott School of Interational Affairs, George Washington University, taught by The East-West Center promotes better relations and Dr. -

DPR Korea: Typhoon Linglingsoulik

Page | 1 DREF Operation Update DPR Korea: Typhoon Lingling DPR Korea: Typhoon Soulik DREF n° MDRKP014 Glide n° TC-2019-000102-PRK Timeframe covered by this update: 6 September 2019 Operation update n° 3: 12 March 2020 to 29 February 2020 Operation start date: 6 September 2019 Operation timeframe: 8 months and end 6 May 2020 DREF amount initially allocated: CHF 56,285 Revised DREF budget: CHF 423,443 2nd allocation amount: CHF 367,158 N° of people being assisted: 27,801 (7,377 households) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: The National Society works with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in this operation. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: The State Committee on Emergency and Disaster Management (SCEDM) Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: The major change to this emergency plan of action is to formalize an extraordinary No-Cost extension of two months of DREF timeline, until 6 May 2020. The extension is contributed to finalize the pending activities and payments due to cash liquidity issue and COVID-19 outbreak. The activities like procurement of RC backpack, spare parts for DPRK RCS vehicles which mobilized for DREF Operation, transportation of Essential Household items for rebalancing stockings of DP warehouses, etc. were delayed because the physical cash transfer channel was blocked due to COVID-19 outbreak and subsequent closure of borders to prevent the spread of virus from China . The normal fund transfer through bank channels are non-existent in DPRK due to UN sanctions. -

China Russia

1 1 1 1 Acheng 3 Lesozavodsk 3 4 4 0 Didao Jixi 5 0 5 Shuangcheng Shangzhi Link? ou ? ? ? ? Hengshan ? 5 SEA OF 5 4 4 Yushu Wuchang OKHOTSK Dehui Mudanjiang Shulan Dalnegorsk Nongan Hailin Jiutai Jishu CHINA Kavalerovo Jilin Jiaohe Changchun RUSSIA Dunhua Uglekamensk HOKKAIDOO Panshi Huadian Tumen Partizansk Sapporo Hunchun Vladivostok Liaoyuan Chaoyang Longjing Yanji Nahodka Meihekou Helong Hunjiang Najin Badaojiang Tong Hua Hyesan Kanggye Aomori Kimchaek AOMORI ? ? 0 AKITA 0 4 DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S 4 REPUBLIC OF KOREA Akita Morioka IWATE SEA O F Pyongyang GULF OF KOREA JAPAN Nampo YAMAJGATAA PAN Yamagata MIYAGI Sendai Haeju Niigata Euijeongbu Chuncheon Bucheon Seoul NIIGATA Weonju Incheon Anyang ISIKAWA ChechonREPUBLIC OF HUKUSIMA Suweon KOREA TOTIGI Cheonan Chungju Toyama Cheongju Kanazawa GUNMA IBARAKI TOYAMA PACIFIC OCEAN Nagano Mito Andong Maebashi Daejeon Fukui NAGANO Kunsan Daegu Pohang HUKUI SAITAMA Taegu YAMANASI TOOKYOO YELLOW Ulsan Tottori GIFU Tokyo Matsue Gifu Kofu Chiba SEA TOTTORI Kawasaki KANAGAWA Kwangju Masan KYOOTO Yokohama Pusan SIMANE Nagoya KANAGAWA TIBA ? HYOOGO Kyoto SIGA SIZUOKA ? 5 Suncheon Chinhae 5 3 Otsu AITI 3 OKAYAMA Kobe Nara Shizuoka Yeosu HIROSIMA Okayama Tsu KAGAWA HYOOGO Hiroshima OOSAKA Osaka MIE YAMAGUTI OOSAKA Yamaguchi Takamatsu WAKAYAMA NARA JAPAN Tokushima Wakayama TOKUSIMA Matsuyama National Capital Fukuoka HUKUOKA WAKAYAMA Jeju EHIME Provincial Capital Cheju Oita Kochi SAGA KOOTI City, town EAST CHINA Saga OOITA Major Airport SEA NAGASAKI Kumamoto Roads Nagasaki KUMAMOTO Railroad Lake MIYAZAKI River, lake JAPAN KAGOSIMA Miyazaki International Boundary Provincial Boundary Kagoshima 0 12.5 25 50 75 100 Kilometers Miles 0 10 20 40 60 80 ? ? ? ? 0 5 0 5 3 3 4 4 1 1 1 1 The boundaries and names show n and t he designations us ed on this map do not imply of ficial endors ement or acceptance by the United N at ions. -

25 Interagency Map Pmedequipment.Mxd

Onsong Kyongwon North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Provision of Medical Equipment Musan Chongjin City Taehongdan Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Chagang Kanggye City Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Responsible Agency Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon WHO Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City UNFPA Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon UNICEF Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon IFRC Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan EUPS 1 Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Sunchon City Kowon EUPS 3 Sukchon SouthSinyang Sudong Pyongsong City Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon EUPS 7 PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Free Trade Zone Kangso Sinpyong Popdong PyongyangKangnam North Thongchon Onchon Junghwa Yonsan Kosan Taean Sangwon No Access Allowed Nampo City Hwanghae Hwangju Koksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City South Singye Kangwon Changdo Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Hwanghae Jaeryong Songhwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Map compliled by VAM Unit Kangryong WFP DPRK Feb 2010. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

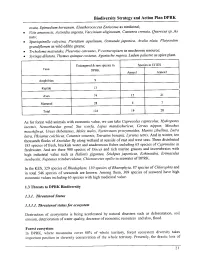

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Pueblo—A Retrospective Richard Mobley U.S

Naval War College Review Volume 54 Article 10 Number 2 Spring 2001 Pueblo—A Retrospective Richard Mobley U.S. Navy Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Mobley, Richard (2001) "Pueblo—A Retrospective," Naval War College Review: Vol. 54 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol54/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mobley: Pueblo—A Retrospective PUEBLO A Retrospective Commander Richard Mobley, U.S. Navy orth Korea’s seizure of the U.S. Navy intelligence-collection—officially, N“environmental research”—ship USS Pueblo (AGER 2) on 23 January 1968 set the stage for a painful year of negotiations. Diplomacy ultimately freed the crew; Pyongyang finally released the men in December 1968. However, in the first days of the crisis—the focus of this article—it was the military that was called upon to respond. Naval power would have played an important role in any immediate attempts to force the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea to re- lease the crew and ship. Failing that, the Seventh Fleet would have been on the forefront of any retaliation. Many works published over the last thirty-three years support this view.1 However, hundreds of formerly classified documents released to the public in the late 1990s offer new insight into many aspects of the crisis. -

DPRK) So Far This Year

DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S 16 April 2004 REPUBLIC OF KOREA Appeal No. 01.68/2004 Appeal Target: CHF 14, 278, 310 Programme Update No. 01 Period covered: January – March 2004 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilising the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organisation and its millions of volunteers are active in over 180 countries. For more information: www.ifrc.org In Brief Appeal coverage: 36.3 %; See attached Contributions List for details. Outstanding needs: CHF 9,089,504 Related Emergency or Annual Appeals: 01.67/2003 Programme Summary: No major natural disasters have affected the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea (DPRK) so far this year. Food security is a major concern, especially in areas remote from the capital. The Red Cross Society of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK RC) has been granted permission from the government to expand the Federation supported health and care programme to another province, increasing the number of potential beneficiaries covered by the essential medicines programme to 8.8 million from July 2004. Due to delayed funding, the first quarter of 2004 has been used to finalise most of the programme activities from the 2003 appeal. Bilateral support from the Republic of Korea, the Netherlands and the Norwegian Red Cross Societies is supplementing Federation support. Partner national societies renewed their commitment to continue supporting DPRK RC. DPRK RC is regarded as an important organisation in DPRK by the government, donor country embassies, UN agencies and NGOs. Operational developments Harvests last year in DPRK were above average, however, the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) state that, despite the good harvests, the situation remains “especially precarious” for young children, pregnant and nursing women and many elderly people. -

The Chosin Chronology Battle of the Changjin Reservoir, 1950

THE CHOSIN CHRONOLOGY BATTLE OF THE CHANGJIN RESERVOIR, 1950 George A. Rasula OPEN with maps by Melville J. Coolbaugh HOW TO USE THIS E-BOOK This electronic book, or “E-Book,” is viewed with Adobe’s Acrobat Reader or any web browser such as Internet Explorer or Netscape. To maneuver through this book use the following buttons at the bottom of your Acrobat window: Window shows which page you’re viewing Moves forward or backward and allows navigation to a particular page. to LAST VIEWED page like an internet browser works. Goes to book’s Advances to beginning. end of book. place Goes to Advances to previous page. next page. VIEWING OF TEXT, PHOTOS & MAPS: Will be greatly enhanced by using the zoom function which Acrobat is capable of. HYPERLINKS: Hyperlinks are text or graphics which are “linked” to another page in the book. When the cursor is moved over this area it changes to a hand pointing its index finger. An example is on the previous, cover page: At the bottom right is an arrow with “Open” which, if clicked, brings you to this page. When finished viewing that page you may go back to your previous spot in the book by clicking the small back arrow (shown above as “LAST VIEWED”). The entire table of contents and index is linked to its page in this book. From any chapter title, sub- chapter heading or page number in the table of contents or index you may go directly to that page simply by clicking on it. There are many other functions of Acrobat that are useful to know and may be learned about under the Help menu of the program.