Psaudio Copper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pogues If I Should Fall from Grace with God Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Pogues If I Should Fall From Grace With God mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: If I Should Fall From Grace With God Country: Canada Released: 2004 Style: Alternative Rock, Folk Rock, Punk MP3 version RAR size: 1240 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1832 mb WMA version RAR size: 1740 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 303 Other Formats: VOC AC3 ASF AU TTA DXD DMF Tracklist Hide Credits 1 If I Should Fall From Grace With God 2:21 2 Turkish Song Of The Damned 3:27 3 Bottle Of Smoke 2:47 Fairytale Of New York 4 4:36 Vocals – Kirsty MacColl Metropolis 5 2:50 Written-By – The Pogues 6 Thousands Are Sailing 5:28 7 Fiesta 4:13 Medley: The Recruiting Sergeant / The Rocky Road To Dublin / The Galway Races 8 4:01 Arranged By – The PoguesWritten By – Traditional 9 Streets Of Sorrow / Birmingham Six 4:39 10 Lullaby Of London 3:31 11 Sit Down By The Fire 2:18 12 The Broad Majestic Shannon 2:52 Worms 13 1:05 Arranged By – Andrew Ranken, James FearnleyWritten By – Traditional 14 The Battle March (Medley) 4:10 The Irish Rover 15 4:07 Written-By – Joseph Crofts Mountain Dew 16 2:19 Arranged By – The Dubliners, The PoguesWritten By – Traditional 17 Shanne Bradley 3:41 18 Sketches Of Spain 2:14 South Australia 19 3:27 Arranged By – The PoguesWritten By – Traditional Credits Accordion, Piano, Mandolin, Dulcimer, Guitar, Cello, Percussion – James Fearnley Arranged By – Fiachra Trench, James Fearnley Artwork By [Cd Package Design] – Phil Smee Banjo [Tenor], Spoons, Mandolin – Ron Kavana Banjo, Performer [Mandola], Saxophone – Jem Finer Bass, Percussion, -

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975 History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Decadence 1969-76 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") As usual, the "dark age" of the early 1970s, mainly characterized by a general re-alignment to the diktat of mainstream pop music, was breeding the symptoms of a new musical revolution. In 1971 Johnny Thunders formed the New York Dolls, a band of transvestites, and John Cale (of the Velvet Underground's fame) recorded Jonathan Richman's Modern Lovers, while Alice Cooper went on stage with his "horror shock" show. In London, Malcom McLaren opened a boutique that became a center for the non-conformist youth. The following year, 1972, was the year of David Bowie's glam-rock, but, more importantly, Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell formed the Neon Boys, while Big Star coined power-pop. Finally, unbeknownst to the masses, in august 1974 a new band debuted at the CBGB's in New York: the Ramones. The future was brewing, no matter how flat and bland the present looked. Decadence-rock 1969-75 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Rock'n'roll had always had an element of decadence, amorality and obscenity. In the 1950s it caused its collapse and quasi-extinction. -

Nightshiftmag.Co.Uk @Nightshiftmag Nightshiftmag Nightshiftmag.Co.Uk Free Every Month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 299 September Oxford’S Music Magazine 2021

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 299 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2021 Gig, Interrupted Meet the the artists born in lockdown finally coming to a venue near you! Also in this comeback issue: Gigs are back - what now for Oxford music? THE AUGUST LIST return Introducing JODY & THE JERMS What’s my line? - jobs in local music NEWS HELLO EVERYONE, Festival, The O2 Academy, The and welcome to back to the world Bullingdon, Truck Store and Fyrefly of Nightshift. photography. The amount raised You all know what’s been from thousands of people means the happening in the world, so there’s magazine is back and secure for at not much point going over it all least the next couple of years. again but fair to say live music, and So we can get to what we love grassroots live music in particular, most: championing new Oxford has been hit particularly hard by the artists, challenging them to be the Covid pandemic. Gigs were among best they can be, encouraging more the first things to be shut down people to support live music in the back in March 2020 and they’ve city and beyond and making sure been among the very last things to you know exactly what’s going be allowed back, while the festival on where and when with the most WHILE THE COVID PANDEMIC had a widespread impact on circuit has been decimated over the comprehensive local gig guide Oxford’s live music scene, it’s biggest casualty is The Wheatsheaf, last two summers. -

![MP3: Girl Talk: Smash Your Head [Infinite Mixtape #22] Posted by Amy Phillips in Remix, Tour, Remix, Tour on Wed: 09-13-06: 09:00 AM CDT | Permalink](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1533/mp3-girl-talk-smash-your-head-infinite-mixtape-22-posted-by-amy-phillips-in-remix-tour-remix-tour-on-wed-09-13-06-09-00-am-cdt-permalink-181533.webp)

MP3: Girl Talk: Smash Your Head [Infinite Mixtape #22] Posted by Amy Phillips in Remix, Tour, Remix, Tour on Wed: 09-13-06: 09:00 AM CDT | Permalink

Pitchfork: News#38521#38521#38521#38521#38521 Page 3 of 17 Girl Talk is on the road right now, with shows scheduled all the way through December. [MORE...] MP3: Girl Talk: Smash Your Head [Infinite Mixtape #22] Posted by Amy Phillips in remix, tour, remix, tour on Wed: 09-13-06: 09:00 AM CDT | Permalink Mission of Burma Documentary Coming to DVD Legendary Boston post-punks and Pitchfork Music Festival alums Mission of Burma have already proven their resurrected greatness, and now they will share the intimate details of their Lazarus story with the world. On November 21, MVD Visual will release Not a Photograph, a 70-minute documentary DVD about the band's 2002 reunion and the obstacles they had to overcome to make it the success it was and still is. Not a Photograph was directed by David Kleiler, Jr. and Jeff Iwanicki, and, in addition to the recent performances, it includes archival footage from the band's original incarnation, including a performance by the Moving Parts, bassist Clint Conley's and guitarist Roger Miller's first band together. And don't forget-- as previously reported, Miller will share his next Mission of Burma tour diary exclusively with Pitchfork. The tour begins this Friday, September 15, at Seattle's Crocodile Cafe. [MORE...] MP3: Mission of Burma: 2wice Posted by Dave Maher in dvd on Wed: 09-13-06: 07:00 AM CDT | Permalink The Pogues Get Expanded Reissue Treatment When the Pogues finished playing, you howled out for more. And, saints be praised, Rhino Records answered. Now grab a pint or two and get ready to curl up all over again with the Celtic folk-punk band's first five albums, like you've never quite heard them before. -

Nick Cave, Un Concerto a Pagamento in Streaming E Senza Repliche LINK

22/07/2020 14:40 Sito Web rep.repubblica.it La proprietà intellettuale è riconducibile alla fonte specificata in testa pagina. Il ritaglio stampa da intendersi per uso privato Nick Cave, un concerto a pagamento in streaming e senza repliche LINK: https://rep.repubblica.it/ws/detail/generale/2020/07/22/news/nick_cave-262623517/ Nick Cave, un concerto a singolare, nel senso pieno altri l'artista australiano non pagamento in streaming e del termine, perché sarà in ha fatto live streaming da senza repliche 22 Luglio scena da solo, casa nelle settimane 2020 L'artista australiano accompagnato dal passate, fino a quando, in protagonista di uno show pianoforte, senza i giugno, non ha registrato registrato senza band e a fedelissimi Bad Seeds, per questa ora e mezza di porte chiuse a Londra che interpretare molte canzoni musica dal vivo. Più che un andrà in onda una sola del suo straordinario concerto è una performance volta: la fruizione sarà repertorio, brani vecchi e artistica, perché non c'è identica a quello di un live nuovi, alcuni eseguiti per la pubblico, perché sembra vero e proprio di ERNESTO prima volta dal vivo, tutto fuori dal tempo e dallo ASSANTE {{MediaVoti}} / compresi brani tratti dai i spazio, come si vede nella 5 Salva Il 23 luglio, alle 21, primi lavori con Bad Seeds clip che ha presentato si potrà assistere on line e Grinderman fino all'ultimo l'evento, perché Cave è sulla app del sito Dice.Fm a album con la band, il completamente solo "Idiot Prayer: Nick Cave bellissimo e drammatico nell'esecuzione di ventidue Alone at Alexandra Palace", Ghosteen. -

The Pogues Hell's Ditch Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Pogues Hell's Ditch mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Hell's Ditch Country: US Released: 1990 Style: Folk Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1139 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1906 mb WMA version RAR size: 1681 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 791 Other Formats: VOC MOD ADX VQF AHX AUD MPC Tracklist Hide Credits The Sunnyside Of The Street Accordion – J. Fearnley*Acoustic Guitar – P. Chevron*Banjo, Steel Guitar [Lap Steel] – J. 1 2:44 Finer*Bass, Backing Vocals – D. Hunt*Drums – A. Ranken*Mandolin – T. Woods*Vocals – S. MacGowan*Whistle – S. Stacy*Written-By – Finer*, MacGowan* Sayonara Acoustic Guitar – P. Chevron*Backing Vocals – D. Hunt*, P. Chevron*Banjo – J. 2 3:07 Fearnley*Bass – D. Hunt*Drums – A. Ranken*Vocals – S. MacGowan*Whistle – S. Stacy*Written-By – MacGowan* The Ghost Of A Smile Accordion, Piano – J. Fearnley*Acoustic Guitar – P. Chevron*Bass – D. Hunt*Drums – A. 3 2:58 Ranken*Electric Guitar, Mandolin – T. Woods*Vocals – S. MacGowan*Whistle – S. Stacy*Written-By – MacGowan* Hell's Ditch Accordion, Acoustic Guitar – J. Fearnley*Bass – D. Hunt*Cittern – T. Woods*Drums – A. 4 3:03 Ranken*Mandolin, Hurdy Gurdy – J. Finer*Percussion – Pogues*Vocals – S. MacGowan*Whistle – S. Stacy*Written-By – Finer*, MacGowan* Lorca's Novena Accordion, Guitar [Spanish] – J. Fearnley*Backing Vocals – A. Ranken*, D. Hunt*Bass, Bells 5 – D. Hunt*Cittern – T. Woods*Drums, Drums [Bed Side Kit] – A. Ranken*Electric Guitar – P. 4:40 Chevron*Hurdy Gurdy – J. Finer*Vocals – S. MacGowan*Whistle, Harmonica – S. Stacy*Written-By – MacGowan* Summer In Siam Accordion, Acoustic Guitar – P. -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent. -

{PDF EPUB} Pogue Mahone Kiss My Arse the Story of the Pogues by Carol Clerk Pogue Mahone Kiss My Arse: the Story of the Pogues by Carol Clerk

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Pogue Mahone Kiss My Arse The Story of the Pogues by Carol Clerk Pogue Mahone Kiss My Arse: The Story of the Pogues by Carol Clerk. The Introduction is available here. Enjoy. Carol Clerk, former News Editor of Melody Maker , has turned her attention to The Pogues. She’s interviewed Shane MacGowan, Spider Stacy, Jem Finer, Philip Chevron, Darryl Hunt, Andrew Ranken, James Fearnley, Terry Woods, and various colleagues, friends and fans. This intimate look behind the music describes their arguments, drunken spats, love affairs, the marriage of Cait and Elvis Costello, the death of Kirsty MacColl, the illnesses, the drugs, the sackings, the legal actions and through it all their passion for music. The book was released in the United Kingdom in October, 2006. ISBN 1.84609.008.3. Published by Omnibus Press. Pogue Mahone Kiss My Arse: The Story of the Pogues by Carol Clerk. He looks up from the dinner he’s been picking at, drops his knife with an enormous clang, and stares an unblinking, pale-blue stare that’s accusing, terrifying. Shane MacGowan has forgotten all about our appointment, the one we arranged in a phone call two days ago. He has forgotten everything he’s been told by various other Pogues who for weeks, helpfully, have been suggesting to him that he might co-operate with this biography. Certainly, he has forgotten the trail of false starts and aborted interviews that have littered the way to our meeting here this evening. The instructions had been vague enough to be worrying: “I’ll be in The Boogaloo on Thursday night.” “Somewhere between nine o’clock and midnight.” The Boogaloo, described by GQ magazine as “the sweetest little juke-joint in all the world”, is a pub and a venue for live music and literary celebration, high up in north London on the Archway Road. -

Dirty Old Town C – 1949 Ewan Maccoll 4/4 C / / / / / F I Met My Love by the Gas Works Wall

Dirty Old Town C – 1949 Ewan MacColl 4/4 C / / / / / F I met my love by the gas works wall. Dreamed a dream / C / / / / by the old canal. I kissed my girl by the factory wall. C G / Am / Dirty old town, dirty old town. C / / / F / Clouds are drifting across the moon. Cats are prowling on their C / / / / feet. Spring's a girl from the streets at night. C G / Am / Dirty old town, dirty old town. C / / / F / I heard a siren from the docks. Saw a train set the night on C / / / / fire. I smelled the spring on the smoky wind. C G / Am / Dirty old town, dirty old town. C / / / F / I'm gonna make me a good sharp axe. Shining steel tempered C / / / / in the fire. I'll chop you down like an old dead tree. C G / Am / Dirty old town, dirty old town. C / / / / F I met my love by the gas works wall. Dreamed a dream / C / / / / by the old canal. I kissed my girl by the factory wall. C G / Am / ||: Dirty old town, dirty old town. :|| repeat and fade Written about Salford, Lancashire, England where MacColl grew up. Popular version by the Pogues and the Dubliners. 3/13/2021 Dirty Old Town G – 1949 Ewan MacColl 4/4 G / / / / / C I met my love by the gas works wall. Dreamed a dream / G / / / / by the old canal. I kissed my girl by the factory wall. G D / Em / Dirty old town, dirty old town. G / / / C / Clouds are drifting across the moon. -

Abkco Records Finds Atc Monitors Critical

ABKCO RECORDS FINDS ATC MONITORS CRITICAL ATC (Acoustic Transducer Company) SCM50 monitors used by ABKCO Records for the Sam Cooke Re- mastered Series. NEW YORK, NEW YORK: Recently in the news with their landmark reissue of 22 early Rolling Stones and five Sam Cooke albums on hybrid Super Audio Compact Disc, ABKCO Records has installed a stereo pair of ATC SCM50ASL Pro active three-way monitor speakers in the company's pre-production listening environment. Ideally suited to medium-sized rooms, the ATC SCM50 reference monitors are primarily used for such critical tasks as archive research, track sequencing, and quality control of digitally re-mastered material at ABKCO's Manhattan facility. They're very musical and have great mid-range, and they're so accurate," says chief audio engineer and tape archive researcher Teri Landi of the ATC monitors. ATC manufactures all of its monitor system component parts in-house, including the company's unique SM75-150S mid-range soft dome driver, which is combined with an ATC 234mm (9-inch) Super Linear bass driver in the SCM50. The ATC Super Linear woofer is the best woofer in production anywhere. The active design of the SCM50 ensures optimum matching of six MOS-FET amp blocks to the drivers. In addition to a flat reference response, an LF contour control offers five bass boost settings. The facility that I have here is a pre-production studio which contains vintage and state-of-the-art equipment," she explains. One of Landi's tasks is to research the company's archive of original analog recordings. -

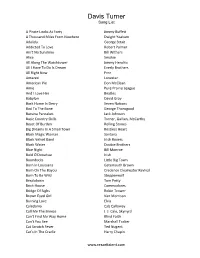

Davis Turner Song List

Davis Turner Song List A Pirate Looks At Forty Jimmy Buffett A Thousand Miles From Nowhere Dwight Yoakum Adalida George Strait Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Alice Smokie All Along The Watchtower Jimmy Hendrix All I Have To Do Is Dream Everly Brothers All Right Now Free Amazed Lonestar American Pie Don McClean Amie Pure Prairie League And I Love Her Beatles Babylon David Gray Back Home In Derry Seven Nations Bad To The Bone George Thorogood Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Basic Country Skills Turner, Gallian, McCarthy Beast Of Burden Rolling Stones Big Dreams In A Small Town Restless Heart Black Magic Woman Santana Black Velvet Band Irish Rovers Black Water Doobie Brothers Blue Night Bill Monroe Bold O'Donahue Irish Boondocks Little Big Town Born In Louisiana Gatemouth Brown Born On The Bayou Credence Clearwater Revival Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf Breakdown Tom Petty Brick House Commodores Bridge Of Sighs Robin Trower Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Burning Love Elvis Caledonia Cab Calloway Call Me The Breeze J. J. Cale, Skynyrd Can't Find My Way Home Blind Faith Can't You See Marshall Tucker Cat Scratch Fever Ted Nugent Cat's In The Cradle Harry Chapin www.resorttalent.com Charlie On The MTA Kingston Trio Chicken Fried Zack Brown China Grove Doobie Brothers City Of New Orleans Arlo Guthrie Cocaine J. J. Cale, Eric Clapton Cold Shot Stevie Ray Vaughn Come Monday Jimmy Buffett Come Out Ye Black And Tans Irish Cool Change Little River Band Copper Head Road Steve Earl Couldn't Stand The Weather Stevie Ray Vaughn