Christian Doctrine in the Poetry of TS Eliot and W. H. Auden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TS ELIOT's PLAYS and RECEPTION Eliot's

T.S. ELIOT’s PLAYS and RECEPTION Eliot’s plays, which begin with Sweeney Agonistes (published 1926; first performed in 1934) and end with The Elder Statesman (first performed 1958; published 1959), are, with the exception of Murder in the Cathedral (published and performed 1935), inferior to the lyric and meditative poetry. Eliot’s belief that even secular drama attracts people who unconsciously seek a religion led him to put drama above all other forms of poetry. All his plays are in a blank verse of his own invention, in which the metrical effect is not apprehended apart from the sense; thus he brought “poetic drama” back to the popular stage. The Family Reunion (1939) and Murder in the Cathedral are Christian tragedies—the former a tragedy of revenge, the latter of the sin of pride. Murder in the Cathedral is a modern miracle play on the martyrdom of Thomas Becket. The most striking feature of this, his most successful play, is the use of a chorus in the traditional Greek manner to make apprehensible to common humanity the meaning of the heroic action. The Family Reunion (1939) was less popular. It contains scenes of great poignancy and some of the finest dramatic verse since the Elizabethans, but the public found this translation of the story of Orestes into a modern domestic drama baffling and was uneasy at the mixture of psychological realism, mythical apparitions at a drawing-room window, and a comic chorus of uncles and aunts. After World War II, Eliot returned to writing plays with The Cocktail Party in 1949, The Confidential Clerk in 1953, and The Elder Statesman in 1958. -

Unit-1 T. S. Eliot : Religious Poems

UNIT-1 T. S. ELIOT : RELIGIOUS POEMS Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 ‘A Song for Simeon’ 1.3 ‘Marina’ 1.4 Let us sum up 1.5 Review Questions 1.6 A Select Bibliography 1.0 Objectives The present unit aims at acquainting you with some of T.S. Eliot’s poems written after his confirmation into the Anglo-Catholic Church of England in 1927. With this end in view, this unit takes up a close reading of two of his ‘Ariel Poems’ and focuses on some traits of his religious poetry. 1.1 Introduction Thomas Stearns Eliot was born on 26th September, 1888 at St. Louis, Missouri, an industrial city in the center of the U.S.A. He was the seventh and youngest child of Henry Ware Eliot and Charlotte Champe Stearns. He enjoyed a long life span of more than seventy-five years. His period of active literary production extended over a period of forty-five years. Eliot’s Calvinist (Puritan Christian) ancestors on father’s side had migrated in 1667 from East Coker in Somersetshire, England to settle in a colony of New England on the eastern coast of North America. His grandfather, W.G. Eliot, moved in 1834 from Boston to St. Louis where he established the first Unitarian Church. His deep academic interest led him to found Washington University there. He left behind him a number of religious writings. Eliot’s mother was an enthusiastic social worker as well as a writer of caliber. His family background shaped his poetic sensibility and contributed a lot to his development as a writer, especially as a religious poet. -

Newsletter 25

An Appeal for Expertise in Accountancy The Society would be very grateful to hear from any member living in the UK who has some knowledge of accountancy, and who would be willing to donate perhaps two hours of his or her time, once a year, in order to prepare a simple account of the Society's income and outgo. Ideally this would be someone living in or relatively near The London. If you fit this description, could you kindly get in touch with the Society at the postal address listed elsewhere on this page? W. H. Auden Society Memberships and Subscriptions Newsletter Annual memberships include a subscription to the Newsletter: Individual members £ 9 $15 ● Students £ 5 $8 Number 25 January 2005 Institutions £ 18 $30 New members of the Society and members wishing to renew should send sterling cheques or checks in US dollars payable to “The W. H. Auden Society” to Katherine Bucknell, 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW. Receipts available on request. Payment may also be made by credit card through the Society’s web site at: http://audensociety.org/membership.html The W. H. Auden Society is registered with the Charity Commission for England and Wales as Charity No. 1104496. Submissions to the Newsletter may be sent in care of Katherine Bucknell, 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW, or by e-mail to: [email protected] All writings by W. H. Auden in this issue are copyright 2005 by The Estate of W. H. Auden. 28 Foster’s recordings has been released in the Windyridge Variety series (www.musichallcds.com) and a brief excerpt may be heard at www.audensociety.org/vivianfoster.html on the Society’s website. -

T. S. Eliot Collection

T. S. Eliot Collection Books and Pamphlets (unless otherwise noted, the first listing after each Gallup number is a first edition) The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock in Poetry. A Magazine of Verse. Edited by Harriet Monroe. June 1915. Gallup C18. The first appearance of the poem. Near fine copy. A2 Ezra Pound: His Metric and Poetry, Alfred A. Knopf, 1917 [i.e. 1918]. Good copy, a bit worn and faded. A4 Ara Vus Prec, The Ovid Press, 1920. Very good copy, light wear. Poems, Alfred A. Knopf, 1920 (first American edition), Head of spine chipped, otherwise very good. A5 The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism. Alfred A. Knopf, 1921 (American issue). Fine in chipped dust jacket. ----- Alfred A. Knopf, 1930 (American issue). Good, no dust jacket. The Waste Land in The Dial, Vol. LXXIII, Number 5, November 1922. Gallup C135. Published “almost simultaneously” in The Criterion. Extremities of spine chipped, otherwise a very good copy. A8 Poems: 1909-1925, Faber & Gwyer Ltd., 1925 (first edition, ordinary copies). Very good, no dust jacket. ----- Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1932 (first American edition). Good only, no dust jacket. Poems: 1909-1925. Faber & Faber, 1932. Reset edition. Fine in dust jacket. 1 T. S Eliot Collection A9 Journey of the Magi, Faber & Gwyer Ltd., 1927. Very good. ----- Faber & Gwyer Ltd., 1927 (limited copies). Fine copy. ----- William Edwin Rudge, 1927 (first American edition). Copyright issue, one of only 27 copies. Fine copy. A10 Shakespeare and the Stoicism of Seneca, Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1927. Very good. A11 A Song for Simeon, Faber & Gwyer Ltd., 1928. -

Newsletter 32

The W. H. Auden Society Newsletter Number 32 ● July 2009 Memberships and Subscriptions Annual memberships include a subscription to the Newsletter: Contents Individual members £9 $15 Katherine Bucknell: Edward Upward (1903-2009) 5 Students £5 $8 Nicholas Jenkins: Institutions and paper copies £18 $30 Lost and Found . and Offered for Sale 14 Hugh Wright: W. H. Auden and the Grasshopper of 1955 16 New members of the Society and members wishing to renew should David Collard: either ( a) pay online with any currency by following the link at A New DVD in the G.P.O. Film Collection 18 http://audensociety.org/membership.html Recent and Forthcoming Books and Events 24 or ( b) use postal mail to send sterling (not dollar!) cheques payable to “The W. H. Auden Society” to Katherine Bucknell, Memberships and Subscriptions 26 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW, Receipts available on request. A Note to Members The W. H. Auden Society is registered with the Charity Commission for England and Wales as Charity No. 1104496. The Society’s membership fees no longer cover the costs of printing and mailing the Newsletter . The Newsletter will continue to appear, but The Newsletter is edited by Farnoosh Fathi. Submissions this number will be the last to be distributed on paper to all members. may be made by post to: The W. H. Auden Society, Future issues of the Newsletter will be posted in electronic form on the 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW; or by Society’s web site, and a password that gives access to the Newsletter e-mail to: [email protected] will be made available to members. -

Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival 2008 Program

July 19 – September 19, 2014 World-class theatre. Right next door. Henry IV • The Merry Wives of Windsor • ShakeScenes • Much Ado About Nothing program_cover_art2014.indd 1 6/30/14 1:36 PM Laura & Jack B. Smith, Jr. are proud sponsors of NOTRE DAME SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL Giving Back to the Community TABLE OF CONTENTS 2–4 About Shakespeare at Notre Dame and the Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival 5 A Note from the Ryan Producing Artistic Director 6 Festival Events and Ticket Information 8–10 Welcome to the 2014 Season 12–15 Professional Company: HENRY IV 17–19 Young Company: THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR 21–22 ShakeScenes 25–26 Actors From The London Stage: MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING 29–39 Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival Cast and Company Profiles 40 Sponsors, Endowments, and Benefactors INSIDE BACK COVER Acknowledgments Festival Production Photographer — Peter Ringenberg LEFT: Robert Jenista, Tim Hanson, Ross Henry, and Kyle CENTER: Young Company Director West Hyler and RIGHT: Cheryl Turski instructs the Young Company in a Techentin work on the HENRY IV set. Stage Manager Nellie Petlick lead a rehearsal of THE movement class. MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR. SHAKESPEARE AT NOTRE DAME Dear Friends: Dear Friends: Here we are again: summer at Notre Welcome to the 2014 season of the Dame and that means the Notre Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival. It’s Dame Shakespeare Festival. a year of celebrations for all things Shakespeare here on campus. 2014 As always, there are the rich and var- marks not only Shakespeare’s 450th ied delights of local groups perform- birthday, but also the 150th anni- ing in ShakeScenes. -

First Name Initial Last Name

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Sarah E. Fass. An Analysis of the Holdings of W.H. Auden Monographs at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Rare Book Collection. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. April, 2006. 56 pages. Advisor: Charles B. McNamara This paper is an analysis of the monographic works by noted twentieth-century poet W.H. Auden held by the Rare Book Collection (RBC) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It includes a biographical sketch as well as information about a substantial gift of Auden materials made to the RBC by Robert P. Rushmore in 1998. The bulk of the paper is a bibliographical list that has been annotated with in-depth condition reports for all Auden monographs held by the RBC. The paper concludes with a detailed desiderata list and recommendations for the future development of the RBC’s Auden collection. Headings: Auden, W. H. (Wystan Hugh), 1907-1973 – Bibliography Special collections – Collection development University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Rare Book Collection. AN ANALYSIS OF THE HOLDINGS OF W.H. AUDEN MONOGRAPHS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL’S RARE BOOK COLLECTION by Sarah E. Fass A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. -

Unit-42 Modern British Poetry an Introduction

This course material is designed and developed by Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), New Delhi. OSOU has been permitted to use the material. Master of Arts ENGLISH (MAEG) MEG-02 BRITISH DRAMA Block – 7 Murder in the Cathedral UNIT-1 T.S. ELIOT’S ESSAYS AND OTHER WORKS RELATED TO THE PLAY UNIT-2 BACKGROUND, PRODUCTION AND PERFORMANCE HISTORY UNIT-3 CRITICAL APPROACHES TO THE PLAY PART-I UNIT-4 CRITICAL APPROACHES TO THE PLAY PART-II UNIT-5 GENERAL COMMENTS AND OTHER READINGS UNIT 1 T.S. ELIOT’S ESSAYS AND OTHER WORKS RELATED TO THE PLAY Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction: Life and Works of T.S. Eliot 1.2 Dramatic Experiments : Sweeney Agonistes and The Rock 1.3 Eliot‘s essays relevant to his plays 1.4 Eliot‘s Poetic dramas 1.5 Exercises 1.0 OBJECTIVES This Unit will familiarise you with T.S. Eliot‘s: a. Life and works b. Dramatic experiments : Sweeney Agonistes and The Rock c. Essays relevant to his plays; and his d. Poetic dramas 1.1 INTRODUCTION : LIFE AND WORKS OF T.S. ELIOT Thomas Steams Eliot was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on 26th September, 1888. William Green Leaf Eliot (Eliot‘s grandfather from his father‘s side) was one of the earliest Eliot settlers in St. Louis. He was a Unitarian minister. Unitarianism arose in America in the mid eighteenth century as a wave against Puritanism and its beliefs in man‘s innate goodness and the doctrine of damnation. Unitarianism perceived God as kind. In 1834 William Green Leaf Eliot established a Unitarian church in St.Louis. -

Simply Eliot

Simply Eliot Simply Eliot JOSEPH MADDREY SIMPLY CHARLY NEW YORK Copyright © 2018 by Joseph Maddrey Cover Illustration by José Ramos Cover Design by Scarlett Rugers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-943657-25-4 Brought to you by http://simplycharly.com Extracts taken from The Poems of T. S. Eliot Volume 1, The Complete Poems and Plays, The Complete Prose of T. S. Eliot: The Critical Edition, The Letters of T. S. Eliot, Christianity and Culture, On Poetry and Poets, and To Criticize the Critic, Copyright T. S. Eliot / Set Copyrights Limited and Reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. Extracts taken from Ash Wednesday, East Coker and Little Gidding, Copyright T. S. Eliot / Set Copyrights Ltd., first appeared in The Poems of T. S. Eliot Volume 1. Reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. Excerpts from Ash Wednesday, East Coker and Little Gidding, from Collected Poems 1909-1962 by T. S. Eliot. Copyright 1936 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Copyright renewed 1964 by Thomas Stearns Eliot. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Extracts taken from Murder in the Cathedral, The Cocktail Party, The Confidential Clerk, and The Elder Statesman, Copyright T. -

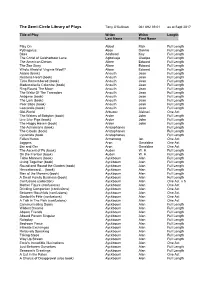

The Semi-Circle Library of Plays Tony O'sullivan 061 692 39 01 As at Sept 2017

The Semi-Circle Library of Plays Tony O'Sullivan 061 692 39 01 as at Sept 2017 Title of Play Writer Writer Length Last Name First Name . Play On Abbot Rick Full Length Pythagorus Abse Dannie Full Length Bites Adshead Kay Full Length The Christ of Coldharbour Lane Agboluaje Oladipo Full Length The American Dream Albee Edward Full Length The Zoo Story Albee Edward Full Length Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Albee Edward Full Length Ardele (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Restless Heart (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Time Remembered (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Mademoiselle Colombe (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Ring Round The Moon Anouilh Jean Full Length The Waltz Of The Toreadors Anouilh Jean Full Length Antigone (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length The Lark (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Poor Bitos (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Leocardia (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Old-World Arbuzov Aleksei One Act The Waters of Babylon (book) Arden John Full Length Live Like Pigs (book) Arden John Full Length The Happy Haven (book) Arden John Full Length The Acharnians (book) Aristophanes Full Length The Clouds (book) Aristophanes Full Length Lysistrata (book Aristophanes Full Length Fallen Heros Armstrong Ian One Act Joggers Aron Geraldine One Act Bar and Ger Aron Geraldine One Act The Ascent of F6 (book) Auden W. H. Full Length On the Frontier (book) Auden W. H. Full Length Table Manners (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Living Together (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Round and Round the Garden (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Henceforward... -

The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden This volume brings together specially commissioned essays by some of the world’s leading experts on the life and work of W. H. Auden, one of the major English-speaking poets of the twentieth century. The volume’s contributors include a prize-winning poet, Auden’s literary executor and editor, and his most recent, widely acclaimed biographer. It offers fresh perspectives on his work from new and established Auden critics, alongside the views of specialists from such diverse fields as drama, ecological and travel studies. It provides scholars, students and general readers with a comprehensive and authoritative account of Auden’s life and works in clear and accessible English. Besides providing authoritative accounts of the key moments and dominant themes of his poetic development, the Companion examines his language, style and formal innovation, his prose and critical writing and his ideas about sexuality, religion, psychoanalysis, politics, landscape, ecology and globalisation. It also contains a comprehensive bibliography of writings about Auden. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO W. H. AUDEN EDITED BY STAN SMITH © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge -

Funny PARTY (Continued)

NEWSLETTER Vol. 17. No.2 tactics Winter 2009/2010 The ACTORS COMPANY THEATRE Scott Alan Evans, Cynthia Harris & Simon Jones, Co-Artistic Directors What’S T.S. Eliot and his INSIDE: TSE's FUNNY PARTY (continued) ..................2 Funny Party (homas) S(terns) Eliot and the the- T.S. Eliot was born September 26, 1888 in SPRING GALA ater? Sure, there was the huge run- St. Louis, Missouri. His love of literature Save the Date .............3 Taway success of Cats, but beyond and learning began at Harvard, where that, what does the brilliant mind behind he graduated with an A.B. in English TACT Season Recap ..................... 4-5 The Waste Land have to do with theater? Literature in 1909. He became Surprisingly, few people are even aware the secretary for the Harvard TACT/QC Alliance.......5 that T.S. Eliot wrote a single play, let alone Advocate, a literary magazine six of them (and the fragment of a sev- and fell in love with writing FAVE FIVE enth). For those who are aware of Eliot’s poetry. Following Harvard, with Jack Koenig ........6 dramatic work, the play that comes to he studied in Paris at the PA PROGRAM mind most frequently is Murder in the Sorbonne for a year where, What We Did Last Cathedral. While that play is not without after attending lectures by Summer ......................6 its considerable merits, it is rather somber philosopher Henri Bergson, and bears little resemblance to his later Eliot decided to pursue an- MORE BANG for more effervescent work. Eliot’s plays have other degree from Harvard, YOUR BUCKS! ...........7 certainly been overshadowed by his po- this time in philosophy.