Word Processing in Elementary Schools: Seven Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Published In: Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, Vol. 49 (New York: Dekker, 1992), Pp

Published in: Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, vol. 49 (New York: Dekker, 1992), pp. 268-78 Author’s address: [email protected] WORD PROCESSING (HISTORY OF). Definition. The term and concept of “word processing” are by now so widely used that most readers will be already familiar with them. The term, created on the model of “data processing,” is more vague than commonly believed. A human editor, for example, obviously pro- cesses words, but is not what is meant by a “word proces- sor.” A number of software programs process words in one way or another--a concordance or indexing program, for example--but are not understood to be word processing programs.’ The term “word processor” means a facility that records keystrokes from a typewriter-like keyboard, and prints the output onto paper in a separate operation. In the meantime the data is stored, usually in memory or mag- netic media. A word processor also can make improve- ments in the stream of words before they are printed. At their most basic these include the ability to arrange words into lines. An “editor,” such as the infamous EDLINE distributed with the Microsoft Disk Operating System (MS-DOS), lacks the ability to structure lines. Commonly a word processor is understood to be a software program, and in the 1980s and 1990s it usually meant a program written for a microcomputer. However, preceding this period and continuing through it there have been hardware word processors. These are pieces of equip- ment sold for the sole purpose of word processing, con- taining in one package a keyboard, printer, recording and playback device, and in all recent examples a video or liquid crystal display screen. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 269 639 CE 044 490 Welcome to the World of Computers. Part 2. Education Service Center Region 20, San Antonio

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 269 639 CE 044 490 TITLE Welcome to the World of Computers. Part 2. INSTITUTION Education Service Center Region 20, San Antonio, Tex. PUB DATE 86 NOTE 311p.; For part 1, see CE 044 489. T'ortions of reprinted material contain small or broken type. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adult Education; Classroom Techniques; Computer Assisted Instruction; *Computer Literacy; *Computer Oriented Programs; *Computer Software; Databases; Integrated Curriculum; *Learning Activities; *Microcomputers; Postsecondary Education; Program Evaluation; Word Processing IDENTIFIERS BASIC Programing Language; Spreadsheets ABSTRACT A continuation of an earlier manual, this guidewas written to help adult education teachers and their studentsto go beyond the information of part 1 and learnmore about the uses of computers. Although this manual is directed more toward teachers and administrators than toward students, activities for studentsare provided. As in part 1, some of the manual has been writtenso that instruction can be given with or witIouta computer; it can be used in a computer literacy class or as part ofa class in some other area, such as English oz mathematics. This manual is organized in six sections. The first five sections cover the following topics: computer review; software applications (word processing, database, spreadsheets, and BASIC programming); evaluation of software (including an annotated resource guide anda software buyer's guide), graphics, and computer-assisted instruction. Each sectioncontains information (including reprints of materials froma variety of sources), learning activities for students, and test items. Materials are illustrated with line drawings. The final section contains reprints of brief articles about computer literacy. -

PC Software Workshop: Personal Productivity Software

PC Software Workshop: Personal Productivity Software Moderator: Doug Jerger Recorded: November 19, 2004 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X4601.2008 © 2004 Computer History Museum Table of Contents INTRODUCTIONS ........................................................................................................................4 A HISTORY OF T/MAKER............................................................................................................5 AN ASIDE ABOUT ROYAL MCBEE’S LGP-30 ..........................................................................10 BACK TO T/MAKER ...................................................................................................................11 THE SOFTWARE PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION (SPA) AND INDUSTRY GROWING PAINS .............................................................................................................................14 BRØDERBUND SOFTWARE .....................................................................................................16 LIFETREE SOFTWARE .............................................................................................................22 NEED FOR VENTURE CAPITAL ...............................................................................................26 PC Software Workshop: Personal Productivity Software Conducted by Software History Center—Oral History Project Abstract: The participants examined Personal Productivity Software from the perspective of software vendors and developers; historians and members of -

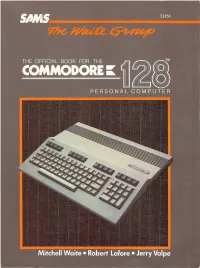

The Commodore 128 1 What's in This Book 2 the Commodore 128: Three Computers in One 3 the C128 Mode 6 the CP/M Mode 9 the Bottom Line 9

The Official Book T {&~ Commodore \! 128 Personal Computer - - ------~-----...::.......... Mitchell Waite, Robert Lafore, and Jerry Volpe The Official Book ~~ Commodore™128 Personal Computer Howard W. Sams & Co., Inc. A Subsidiary of Macmillan, Inc. 4300 West 62nd Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46268 U.S.A. © 1985 by The Waite Group, Inc. FIRST EDITION SECOND PRINTING - 1985 All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical. photocopying, recording, or otherwise, with out written permission from the publisher. No patent liability is assumed with respect to the use of the information contained herein. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. International Standard Book Number: 0-672-22456-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 85-50977 Illustrated by Bob Johnson Typography by Walker Graphics Printed in the United States of America The Waite Group has made every attempt to supply trademark information about company names, products, and services mentioned in this book. The trademarks indicated below were derived from various sources. The Waite Group cannot attest to the accuracy of this information. 8008 and Intel are trademarks of Intel Corp. Adventure is a trademark of Adventure International. Altair 8080 is a trademark of Altair. Apple II is a registered trademark of Apple Computer, Inc. Atari and Atari 800 are registered trademarks of Atari Inc. Automatic Proofreader is a trademark of COMPUTE! Publications. -

List of Word Processors

List of word processors The following is a list of word processors. Entries should • IA Writer - Mac, iOS have a Wikipedia article or a citation to show notability. • Ichitaro - a Japanese word processor produced by JustSystems 1 Free and open-source software • InCopy • AbiWord • IntelliTalk • Apache OpenOffice Writer • iStudio Publisher - Mac • Calligra Words • Kingsoft Writer - Windows and Linux • EtherPad, real time word processor • Lotus Word Pro - Windows • GNU TeXmacs • Mariner Write - Mac • Groff • Mathematica - technical and scientific word process- • JWPce is a Japanese word processor, designed pri- ing marily for the English speaker who is reading or writing in Japanese. • Mellel - Mac • KWord • Microsoft Word - Windows and Mac • LyX • Microsoft Works Word Processor • LibreOffice Writer • Microsoft Write - Windows and Mac (a stripped- • Ted down version of Word) • Polaris Office • Nisus Writer - Mac • Nota Bene - Windows 2 Proprietary software • Polaris Office - Android and Windows Mobile 2.1 Commercial • PolyEdit • Adobe PageMaker • QuickOffice - Android, iOS, Symbian • Apple Pages, part of its iWork suite - Mac • Scrivener • Applix Word - Linux • TechWriter - RISC OS • Atlantis Word Processor - Windows • TextMaker • Documents To Go - Android, iOS, Windows Mo- bile, Symbian • ThinkFree Office Write • Final Draft Screenplay/Teleplay word processor • WordPad, previously known as “Write” in older ver- sions than Windows 95, has been included in all ver- • FrameMaker sions of Windows since Windows 1.01. Source code • Gobe Productive Word Processor -

Information Technologies and Basic Learning. Reading, Writing, Science and Mathematics

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 290 444 IR 012 992 AUTHOR Lesgold, Alan M., Ed. TITLE Information Technologies and Basic Learning. Reading, Writing, Science and Mathematics. INSTITUTION Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris (France). Centre for Educational Research and Innovation. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 270p.; For the final report of Phase Iof this project, see ED 271 056. AVAILABLE FROMOECD Publications and Information Centre, 2001 L Street, N.W., Suite 700, Washington, DC 20036-4095 ($32.00). PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDPS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC No: Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Basic Skills; *Computer Assisted Instruction; *Computer Software; Developed Nations; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Information Technology; *Instructional Improvement; International Cooperation; Mathematics Instruction; Reading Instruction; Research and Development; Science Instruction; Writing (Composition) IDENTIFIERS Centre for Educ Research and Innovation (France); *Cognitive Sciences ABSTRACT This volume marks the completion of Phase II of the Centre for Educational Research and Innovat In (CERI) project of inquiry into the issues inherent in the introduction of new information technologies in education. It summarizes the issues discussed and the recommendations made by four working groups at an international conference, each of which focused on the effects of lew information technologies on instruction in one of the four basic skills, i.e., reading, writing, -

Computers for College Writing: a Promising Beginning

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 289 173 CS 210 870 AUTHOR Styne, Marlys M. TITLE Computers for College Writing: A Promising Beginning. PUB DATE 24 Apr 87 NOTE 22p.; Paper presented at the University of Illinois at Chicago/City Colleges of Chicago Partnership Program Conference "Cultural and Cognitive Approaches to Teaching Writing and Mathematics to Undergraduates" (Chicago, IL, April 24, 1987). PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Computer Assisted Instruction; Computer Software; *Computer Uses in Education; *Freshman Composition; Higher Education; Teacher Administrator Relationship; Teaching Methods; Word Processing; *Writing Instruction; *Writing Laboratories; Writing Research ABSTRACT Noting that computers have fascinated teachers looking for new and better ways of teaching writing, not because the machines make students into better writers, but because they are useful tools that make editing and revising much easier, this paper explores the use of computers to teach writing, based on the experiences of a writing laboratory instructor at Chicago's Wilbur Wright College. The paper first discusses choosing a computer for the laboratory, recommending unconnected microcomputers over mainframes or networks. Next considered is choice of word processing software; full-featured programs are recommended but simpler programs for beginners are also suggested. Other software, such as sp.Illing checkers, outliners, and style checkers are also discussed. Next the document focuses on political issues, such as the relationship of writing laboratories to administration, laboratory scheduling, and money matters. The document then examines the details of working word processing instruction into the freshman composition curriculum, stressing the importance of handouts. Advantages and disadvantages of using computers in composition courses are then enumerated, and the lack of research studies on the topic is noted. -

Pcjr Computer * Pcjr Color Display * Keyboard * Word Processing Software * IBM PC-DOS with Manual #11208

____ kyou’ui Ever Need grade Your I I :1 Ir Computer - This catalog includes IBM PCjr compatible hardware and software. PC Enterprises can also help you upgrade other IBM and Tandy computers including IBM PC, XT, AT, PS/2, 286 and 386 computers. Call our toll free 800 number to request FREE catalogs for any other computers that you may own. * Flat Rate Repair Service NOW Only $99 * Memory Expansions from $99 * Hard Drive Systems from $245 * CD-ROM Drives from $395 * PC1r Compatible Software from $9.95 * Accellerator Boards $99 * PC1r Goodie-Boxes $59.95 486 Systems that work with the PCjr -- Monitor only $599 ENTERPRISES] "Computer Upgrade Specialists Since 1984" - PC Enterprises 2400 Belmar Blvd Bldg B-16 Belmar, NJ 07719 800 922-7257 908 280.0025 _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Upgrading your Existing Computer will Save you Money!! Dear Customer: Today’s software requires a much more powerful computer than could have been imagined just a few years ago. Even if you recently purchased your computer, you have probably already started to crave more memory and a bigger hard drive. Perhaps you want to add something more exciting like a Fax/Modem, a scanner, sound board, CD-ROM drive, or even a color printer’ Very few people are willing to buy a new computer just because somebody came out with something else new. Adding expansion products to the computer you MEMBER already own is the perfect solution. Expansion products allow you to continue using your existing computer, while still using the latest hardware and software products available. Better Business Bureau If you want to upgrade your computer to make it more useful, chances are that of Central New Jersey you will need to purchase very little. -

Office (For Windows & the Mac)

3 definitions of “word processor” A “word processor” is supposed to be “a computer whose main purpose is to do word processing”. But some folks use the term Word “word processor” to mean “a word-processing program” or “a typist doing word processing”. In ads, a “$300 word processor” is a machine; a “$100 word A word-processing program helps you write and edit processor” is a program you feed a computer; a “$12-per-hour sentences and paragraphs. What you’re writing and editing (such word processor” is a typist who understands word processing. as a business letter, report, magazine article, or book) is called the document. Word-processing programs A word-processing program’s main purpose is to manipulate paragraphs. During the early 1980’s, these word-processing programs were To manipulate drawings, get a graphics program instead. popular: To manipulate a table of numbers, get a spreadsheet program. To manipulate a list of names (such as customers), get a database program. Electric Pencil (the first word-processing program for microcomputers), Wordstar (which was more powerful), Multimate (the first program that To use a word-processing program, put your fingers on the made the IBM PC imitate a Wang word-processing machine), Displaywrite keyboard, then type the paragraphs that make up your document, (which made the IBM PC imitate an IBM Displaywriter word-processing so they appear on the screen. Edit them by pressing special keys machine), PC-Write (shareware you could try for free before sending a on the keyboard. Finally, make the computer send the document donation to the author), and Xywrite (which ran faster than any other word to the printer, so the document appears on paper.