Anthology of Peace and Security Research Volume 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Ethiopia: 2015 HRF Projects Map (As of 31 December 2015)

Ethiopia: 2015 HRF projects map (as of 31 December 2015) Countrywide intervention ERITREA Legend UNICEF - Nutrition - $999,753 Concern☃ - VSF-G ☈ ! Refugee camp WFP - Nutrition (CSB) - $1.5m National capital Shimelba Red Sea SUDAN Regional intervention International boundary Hitsa!ts Dalul UNICEF - Health - $1.0m ! !Hitsats ! ! Undetermined boundary ! ! SCI Tigray, Afar, Amhara, Oromia, Kelete Berahile ☃☉ May-Ayni Kola ! Somali, Gambella, SNPR & NRC - ☉ Ts!elemti Temben Awelallo Lake IRC - ★ ! ☄ ! ♫ Tanqua ! SUDAN ! ! ! Dire Dawa Adi Harush ! Enderta Abergele ! Ab Ala Afdera Project woredas Tselemt ! NRC - Debark GAA - ☇ ! WFP (UNHAS) - Coordination ☈ Abergele! Erebti ☋☉ Plan Int. - ACF - ☃ Dabat Sahla ☃Megale Bidu and Support Service - $740,703 Janamora Wegera! Clusters/Activities ! Ziquala Somali region Sekota ! ! Concern - SCI Teru ! Agriculture CRS - Agriculture/Seed - $2,5m ☃ ☃ Kurri ! Dehana ! ☋ ! Gaz Alamata ! Elidar GAA - ☋ Amhara,Ormia and SNNP regions ! ☃☉ Gonder Zuria Gibla ! Gulf of ! Education Plan Int. - Ebenat Kobo SCI☃☉ ☃ ! Gidan ☄ Lasta ! Aden CARE - Lay Guba ! Ewa ! ☃ ! Meket Lafto Gayint ! Food security & livelihood WV - ☃ Dubti ☈ ☉ ! Tach Habru Chifra SCI - ☃ Delanta ! ! - Tigray Region, Eastern Zone, Kelete Awelall, ! Gayint IMC - ☃ Health ☉ Simada Southern Zone, Alamata and Enderta woredas ! ! Mile DJIBOUTI ☊ Mekdela ! Bati Enbise SCI- Nutrition ! Argoba ☃☉ WV - ☃ Sar Midir Legambo ☃ ! Oxfam GB - Enarj ! ☉ ! ! Ayisha Non Food Items - Amhara region, North Gonder (Gonder Zuria), Enawga ! Antsokiya Dalfagi ! ! ! Concern -

Food Supply Prospects - 2009

FOOD SUPPLY PROSPECTS - 2009 Disaster Management and Food Security Sector (DMFSS) Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MoARD) Addis Ababa Ethiopia February 10, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages LIST OF GLOSSARY OF LOCAL NAMES 2 ACRONYMS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 - 8 INTRODUCTION 9 - 12 REGIONAL SUMMARY 1. SOMALI 13 - 17 2. AMHARA 18 – 22 3. SNNPR 23 – 28 4. OROMIYA 29 – 32 5. TIGRAY 33 – 36 6. AFAR 37 – 40 7. BENSHANGUL GUMUZ 41 – 42 8. GAMBELLA 43 - 44 9. DIRE DAWA ADMINISTRATIVE COUNSEL 44 – 46 10. HARARI 47 - 48 ANNEX – 1 NEEDY POPULATION AND FOOD REQUIREMENT BY WOREDA 2 Glossary Azmera Rains from early March to early June (Tigray) Belg Short rainy season from February/March to June/July (National) Birkads cemented water reservoir Chat Mildly narcotic shrub grown as cash crop Dega Highlands (altitude>2500 meters) Deyr Short rains from October to November (Somali Region) Ellas Traditional deep wells Enset False Banana Plant Gena Belg season during February to May (Borena and Guji zones) Gu Main rains from March to June ( Somali Region) Haga Dry season from mid July to end of September (Southern zone of of Somali ) Hagaya Short rains from October to November (Borena/Bale) Jilal Long dry season from January to March ( Somali Region) Karan Rains from mid-July to September in the Northern zones of Somali region ( Jijiga and Shinile zones) Karma Main rains fro July to September (Afar) Kolla Lowlands (altitude <1500meters) Meher/Kiremt Main rainy season from June to September in crop dependent areas Sugum Short rains ( not more than 5 days -

Searching for Cyberspace: Joyce, Borges and Pynchon

Searching for Cyberspace: Joyce, Borges and Pynchon By Davin O’Dwyer Introduction The work of James Joyce, Jorge Luis Borges, and Thomas Pynchon spans the twentieth century, from Joyce’s Dubliners in 1907 to Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon in 1997, a century which started with scientific upheaval and ended with a communications revolution. The novels and stories by these three writers look in both directions, reflecting the new revelations in physics, and anticipating in various ways the advent of our connected society. The purpose of this thesis is to investigate the latter, to see exactly how three of the century’s greatest writers might have been searching for cyberspace, though it is my contention that one cannot be understood without the other, that philosophical thought on quantum physics and philosophical thought on cyberspace are not unrelated. Undoubtedly, both quantum mechanics and cyberspace raise serious questions about our perception of reality, of the concrete world we inhabit, questions all three writers rigorously address. Much has been made of the extraordinary speed with which the Internet has been adopted around the world, and why it has been so instantly successful. In many ways, cyberspace promises to satisfy so many of civilisation’s goals and aspirations: the innate desire to communicate and connect with people all over the globe, and to contract physical space in the process; it offers us the universal library, the definitive collection of all learning and knowledge; it satisfies our desire to understand and control our world. It was this desire to understand, and even control, our world which has always driven scientists and thinkers.(1) Since Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), the universe was deemed to be a mechanistic, clockwork-like system, where every action has an opposite and equal reaction, where gravity is responsible for both the movement of planets and apples, and so on. -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

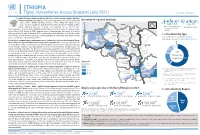

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008)

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008) ma, maa (O) why? HES37 Ma 1258'/3813' 2093 m, near Deresge 12/38 [Gz] HES37 Ma Abo (church) 1259'/3812' 2549 m 12/38 [Gz] JEH61 Maabai (plain) 12/40 [WO] HEM61 Maaga (Maago), see Mahago HEU35 Maago 2354 m 12/39 [LM WO] HEU71 Maajeraro (Ma'ajeraro) 1320'/3931' 2345 m, 13/39 [Gz] south of Mekele -- Maale language, an Omotic language spoken in the Bako-Gazer district -- Maale people, living at some distance to the north-west of the Konso HCC.. Maale (area), east of Jinka 05/36 [x] ?? Maana, east of Ankar in the north-west 12/37? [n] JEJ40 Maandita (area) 12/41 [WO] HFF31 Maaquddi, see Meakudi maar (T) honey HFC45 Maar (Amba Maar) 1401'/3706' 1151 m 14/37 [Gz] HEU62 Maara 1314'/3935' 1940 m 13/39 [Gu Gz] JEJ42 Maaru (area) 12/41 [WO] maass..: masara (O) castle, temple JEJ52 Maassarra (area) 12/41 [WO] Ma.., see also Me.. -- Mabaan (Burun), name of a small ethnic group, numbering 3,026 at one census, but about 23 only according to the 1994 census maber (Gurage) monthly Christian gathering where there is an orthodox church HET52 Maber 1312'/3838' 1996 m 13/38 [WO Gz] mabera: mabara (O) religious organization of a group of men or women JEC50 Mabera (area), cf Mebera 11/41 [WO] mabil: mebil (mäbil) (A) food, eatables -- Mabil, Mavil, name of a Mecha Oromo tribe HDR42 Mabil, see Koli, cf Mebel JEP96 Mabra 1330'/4116' 126 m, 13/41 [WO Gz] near the border of Eritrea, cf Mebera HEU91 Macalle, see Mekele JDK54 Macanis, see Makanissa HDM12 Macaniso, see Makaniso HES69 Macanna, see Makanna, and also Mekane Birhan HFF64 Macargot, see Makargot JER02 Macarra, see Makarra HES50 Macatat, see Makatat HDH78 Maccanissa, see Makanisa HDE04 Macchi, se Meki HFF02 Macden, see May Mekden (with sub-post office) macha (O) 1. -

Hygienic Practice Among Milk and Cottage Cheese Handlers in Districts of Gamo and Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia

Research Article Volume 12:2, 2021 Journal of Veterinary Science & Technology ISSN: 2157-7579 Open Access Knowledge; Hygienic Practice among Milk and Cottage Cheese Handlers in Districts of Gamo and Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia Edget Alembo* Department of Animal Science, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia Abstract A cross-sectional questionnaire survey was conducted in Arba Minch Zuria and Demba Gofa districts of Gamo and Gofa Zone of the Southern nation nationalities and people’s regional state with the objectives of assessing knowledge of hygienic practice of milk and cheese handlers in both study area. For this a total of 102 farmers who involved in milking, collecting and retailing of milk were included in the study area. Data obtained from questionnaire survey were analyzed by descriptive statistics and Chi –square test, using the Statistical package for social science (SPSS Version 17). The participants of this study were woman of different age group and 27(52.9%) of participants in Arba Minch Zuria and 32(64.7%) in Demba Gofa were >36 years old. The majority of participants 21(41.2%) and 22(43.1%) were educated up to grade 1-8 in Arba Minch Zuria and Demba Gofa, respectively. This had an impact on hygienic practice of milking and milk handling. The difference in hygienic handling, training obtained and cheese making practice among the study areas were statistically significant (p<0.05). There was also a statistically significant difference in hand washing and utensil as well as manner of washing between the two study areas (p<0.01). Finally this study revealed that there were no variation in Antibiotic usage and Practice of treating sick animal in both study area (p>0.05) with significant difference in Prognosis, Level of skin infection and Selling practice among study participants in both study areas (p<0.05). -

Amhara Claim of Western and Southern Parts of Tigray

AMHARA CLAIM OF WESTERN AND SOUTHERN PARTS OF TIGRAY By Mathza 11-26-20 We have been hearing and reading about the Amhara Regional State claim of ownership of the Welqayit, Tsegede, Qafta-Humera and Tselemti weredas (hereafter refereed to Welqayit Group) and Raya, and Amhara Regional State threats of war against TPLF/Tigray. One of the threats states “some of the Amhara elite politicians continue to beat drums, as summons to war” (watch/listen) DW TV (Amharic) - July 30, 2020. THE WELQAYIT GROUP Welkayit Amhara Identity Committee (WAIC) was formed in Gonder to return the Welqayit Group from Tigray Regional State to Amhara Regional State. The Welqayit Group was transferred to Tigray during the 1984 reconfiguration of the administrative structure of the country based on ethno-linguistical regional states (kililoch) after the Derg was defeated. It seems that the government of Eritrea has contributed to the Welqayit Group problem. According to ህግደፍንኣሸበርቲ ጉጅለታትን ብአንደበት…ቀዳማይ ክፋል (watch) the Eritrean government had trained Ethiopian oppositions and inculcated opposing views between ethnic groups in Ethiopia, particularly between Amhara and Tigray Regional States, wherever it viewed appropriate for its devilish objective of dismantling Ethiopia. The Committee recruited Tigrayans from Tigray Regional State to do its dirty work. An example is presented in a video, Tigrai Tv:መድረኽተሃድሶ ወረዳ ቃፍታ- ሑመራህዝቢ ጣብያ ዓዲ-ሕርዲ - YouTube (watch) aired on Feb 01, 2017. It shows confessions by a number of Tigrayans from Qafta-Humera who were lured and bribed by the Committee to serve its objectives. Each of them gave details of activities they participated in and carried out against their own people. -

Regreening of the Northern Ethiopian Mountains: Effects on Flooding and on Water Balance

PATRICK VAN DAMME THE ROLE OF TREE DOMESTICATION IN GREEN MARKET PRODUCT VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA afrika focus — Volume 31, Nr. 2, 2018 — pp. 129-147 REGREENING OF THE NORTHERN ETHIOPIAN MOUNTAINS: EFFECTS ON FLOODING AND ON WATER BALANCE Tesfaalem G. Asfaha (1,2), Michiel De Meyere (2), Amaury Frankl (2), Mitiku Haile (3), Jan Nyssen (2) (1) Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Mekelle University, Ethiopia (2) Department of Geography, Ghent University, Belgium (3) Department of Land Resources Management and Environmental Protection, Mekelle University, Ethiopia The hydro-geomorphology of mountain catchments is mainly determined by vegetation cover. This study was carried out to analyse the impact of vegetation cover dynamics on flooding and water balance in 11 steep (0.27-0.65 m m-1) catchments of the western Rift Valley escarpment of Northern Ethiopia, an area that experienced severe deforestation and degradation until the first half of the 1980s and considerable reforestation thereafter. Land cover change analysis was carried out using aerial photos (1936,1965 and 1986) and Google Earth imaging (2005 and 2014). Peak discharge heights of 332 events and the median diameter of the 10 coarsest bedload particles (Max10) moved in each event in three rainy seasons (2012-2014) were monitored. The result indicates a strong re- duction in flooding (R2 = 0.85, P<0.01) and bedload sediment supply (R2 = 0.58, P<0.05) with increas- ing vegetation cover. Overall, this study demonstrates that in reforesting steep tropical mountain catchments, magnitude of flooding, water balance and bedload movement is strongly determined by vegetation cover dynamics. -

PETROS III (D. 1607) Petros Was Certainly the Successor Of

PETROS III (d. 1607) Petros was certainly the successor of Krestodolu I, but in Ethiopian documents, information about his episcopate is fragmentary and scant, perhaps explained by the fact that the annals of the sovereigns of his time do not survive. Only the manifesto issued around 1624 by Negus Susenyos (1607-1632) in an effort to explain his joining the Catholic church gives a summary view of this episcopate. Denouncing the conduct of certain metropolitans in Ethiopia, this negus wrote: Abuna Petros [III], who succeeded this metropolitan [Krestodolu I], had relations with the wife of a Melchite, and when this fact became public, he paid the fine levied against any adulterer who corrupts the wife of another; certain witnesses having knowledge of this are still living, such as Joseph and Marino, who are foreigners not Ethiopians. Moreover, to this sin the metropolitan added other misdeeds. In the seventh year of Negus Ya‘qob's reign, Petros [III] issued a general excommunication which caused the people to depose Yaqob, exile him to Ennarya, and replace him with Za-Dengel. Later, he [Petros III] issued a second general excommunication in order to persuade the Ethiopians to get rid of Negus Za-Dengel, who was in fact killed [and replaced by Ya‘qob]. And as if that were not enough, when we [Susenyos] decided to fight against Negus Ya‘qob, the metropolitan [Petros III] went to war with him and fell with him on the battlefield. The essential facts referred to in this passage from Susenyos' manifesto must be summarized. Sarsa Dengel had had no male offspring by his wife Maryam Sena, but at his death he did leave some illegitimate sons. -

Democracy Under Threat in Ethiopia Hearing Committee

DEMOCRACY UNDER THREAT IN ETHIOPIA HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 9, 2017 Serial No. 115–9 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 24–585PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:13 Apr 20, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_AGH\030917\24585 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina AMI BERA, California MO BROOKS, Alabama LOIS FRANKEL, Florida PAUL COOK, California TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas RON DESANTIS, Florida ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDAN F. BOYLE, Pennsylvania TED S.