Wellington Town Belt Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wellington Town Belt Management Plan – June 2013 49

6 Recreation The play area at Central Park, Brooklyn. A flying fox and bike skills area are also provided. Guiding principles The Town Belt is for all to enjoy. This concerns equity of access and use of the Town Belt. The Council believes that the Town Belt should be available for all Wellingtonians to enjoy. The Council is committed to ensuring that the Town Belt will continue to be improved with more access and improved accessibly features where it is reasonably practicable to do so. The Town Belt will be used for a wide range of recreation activities. The Town Belt should cater for a wide range of sporting and recreation activities managed in a way to minimise conflict between different users. Co-location and intensification of sports facilities within existing hubs and buildings is supported where appropriate. 6.1 Objectives 6.1.1 The Town Belt is accessed and used by the community for a wide range of sporting and recreational activities. 6.1.2 Recreational and sporting activities are environmentally, financially and socially sustainable. 6.1.3 Participation in sport and recreation is encouraged and supported. 6.1.4 The Town Belt makes a significant contribution to the quality of life, health and wellbeing of Wellingtonians by increasing a range of physical activity and providing active transport routes and access to natural environments 6.1.5 The track (open-space access) network provides for a range of user interests, skills, abilities and fitness levels, and pedestrian and cycling commuter links. 6.1.6 Management and development of formal sporting facilities and associated infrastructure does not compromise the landscape and ecological values of the Town Belt. -

61 VICT 1897 No 14 Wellington City Empowering

81 "VICT.] Wellington Oity ErnpouJering. [1897, No. 14. New Zealand. ANALYSIS. Title. PART V. 1. Short Title. 2. Interpretation. WIDENING AND EXTENDING STREETS. 7. Power to improve streets and acquire lands, PART I. and borrow moneys, and sell or lease OVERDRAFTS. surplus lands. 3. Counoil may borrow to extinguisb overdrafts. : 8. Rents and sale· moneys to be applied to loans. Limit of speoial rates. PART n. 9. How and when this Part of Act to come into URGENT WORKS. force. 4. Council may oarry out scheduled works, and PART VI. raise loan for same. BASIN RESERVlil. PART Ill. 10. Part of Basin Reserve thrown into adjoining TOWN HALL. street. 5. Council may sell or lease present munioipal PART VII. site, and borrow to erect new Town Hall. GENERAL PROVISIONS. PART IV. 11. Speoial rates may be struok for loans. 12. Majority on polls. Polling.plaoes. WATER-SUPPLY. 13. Misoellaneous. 11. Counoil may provide supply for higher levels. Scbedules. 1897, No. 14.-Local. AN ACT to confer Further Powers on the Corporation of the City Title. of Wellington. 22nd DeI.Jember, 1897. BE IT ENACTED by the General Assembly of New Zealand in Parliament assembled, and by the authority' of the same, as fol lows :- 1. The Short Title of this Act is "rrhe Wellington City Em- Short Title. powering Act, 1897." 2. In this Act, unless inconsistent with the context, - Interpretation. " City" means the Borough of the City of Wellington: " Corporation" means the Mayor, Councillors, and Citizens of the said city: " Council" means the Council of the said city: "The said Act" means "The Municipal Corpurations Act, 1886." 8* 116 1897, No. -

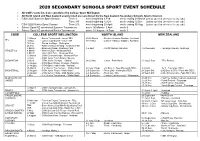

2020 Secondary Schools Sport Event Schedule

2020 SECONDARY SCHOOLS SPORT EVENT SCHEDULE All CSW events listed are sanctioned by College Sport Wellington All North Island and New Zealand events listed are sanctioned by the New Zealand Secondary Schools Sports Council. CSW 2020 Summer Sport Season: Term 1: week beginning 3 Feb week ending 29 March [unless specified otherwise for any code] Term 3/4: week beginning 12 Oct week ending 12 Dec [unless specified otherwise for any code] CSW 2020 Winter Sport Season: Term 2/3: week beginning 28 April week ending 30 Aug [unless specified otherwise for any code] School Sport NZ sanctioned Summer Tournament week: 30 March - 3 April week 9 School Sport NZ sanctioned Winter Tournament week: 31 August - 4 Sept week 7 CODE COLLEGE SPORT WELLINGTON NORTH ISLAND NEW ZEALAND 19 March - Senior Tournament - venue TBA 25-26 March - Seniors -Harbour Stadium, Auckland AFL 10 Nov - Junior Tournament - venue TBA 18-19 Nov - Juniors -Harbour Stadium, Auckland 16 Feb - Round the Bays - Wellington 25 Feb - AWD selection Meeting - Newtown Park 3 March - McEvedy Shield - Newtown Park 3-5 April - Porritt Stadium, Hamilton 4-6 December - Tauranga Domain, Tauranga ATHLETICS 4 March - Western Zone - Newtown Park 5 March - Hutt / Girls Zone - Newtown Park 12 March - CSW Championships - Newtown Park 23 July - CSW Junior Team Finals - Naenae BADMINTON 29 July - CSW Junior Champs - Haitaitai 24-26 Nov - Junior - Palm North 31 Aug-3 Sept - TRA, Porirua 12 August - CSW Open Singles Champs - Haitaitai 21 August - CSW Open Team Finals - Haitaitai 26 March - 3 x 3 Senior -

Basin Reserve Trust Statement of Service Performance 2019/20

Basin Reserve Trust Statement of Service Performance 2019/20 2 Introduction The iconic Basin Reserve has a rich history. The first game of cricket was played at the Basin on 11 January 1868, making it is the oldest cricket ground in New Zealand. The ground not only hosts cricket games, but sporting fixtures of every variety. It has hosted national events and competitions including VE Day celebrations, Royal Tours, exhibitions, Scout jamborees, concerts and festivals. In 1998, the Basin Reserve was listed as a Heritage Area, becoming the first sports ground to receive such a designation and further enhancing its heritage significance. The Basin is also home to the William Wakefield Memorial that was erected in 1882 and commemorates one of Wellington’s founders, William Wakefield. The Basin Reserve plays a role in assisting Wellington City Council to achieve the recreation and leisure participation aims signalled in the 2018-28 Ten Year Plan and the “Living WELL” Wellington Sport & Active Recreation Strategy. The redevelopment will reposition the Basin as New Zealand’s premier cricket venue and help attract national and international events to Wellington. The day to day management of the Basin Reserve is undertaken by Cricket Wellington under a management agreement with the Basin Reserve Trust (BRT). This Statement of Service Performance highlights the achievements of the Trust for the period July 2019 to June 2020. Objectives The objectives of the trust are stated in the Trust Deed as agreed between the Wellington City Council and the BRT and are highlighted below: 1. to manage, administer, plan, develop, maintain, promote and operate the Basin Reserve for recreation and leisure activities and for the playing of cricket for the benefit of the inhabitants of Wellington 2. -

Section Ii: Other Items

SECTION II: OTHER ITEMS II.i Contents of Miscellaneous Folders II.i.a Britain: Miscellaneous Folder B.E England B.E40 “Society of Brushmakers’ Descendants, Members’ Interest Names, 1997”. B.E39 “How names are in our genes” Observer, Feb. 2001. B.E38 “Update on Places in London [central] Where Records are Located” from Richard Moore. Also “English Poor Laws”, brief notes (incl. list of recommended reading) from Marjorie R. Moore, Jul 2000. 2 pp. B.E37 Family Records, Centre, 1 Myddelton St, London (flyer) B.E36 NORCAP News no.53, 1998 (Nat.Org.for Counselling of Adoptees & Parents) B.E35 Access to Birth Records: counselling organisations outside the United Kingdom; and Access to Birth Records: Information for adopted people living outside the United Kingdom, Office of National Statistics B.E34 Addresses for Genealogical Research in Great Britain & Eire B.E33 Roll of Battle Abbey, A.D. 1066 B.E32 “The modern way to trace your family tree”, from Woman’s Weekly, 1999. B.E31 Review of Anthony Camp talk on occupations in towns, with extensive bibliography B.E30 St Catherines House Indexes - volume nos. by counties, 1992 B.E29 Record repositories, extract from Family Tree Magazine 1996 B.E28 Extract from London Street Directory 1852, & 1854 (2 pp only) B.E27 The modern British army cap badge: a brief guide as to how it evolved, compiled by John McConaghy. 9 pp. B.E26 Research material available to the genealogist in the UK & Europe B.E25 British & Irish Biographies 1840-1940, review B.E24 Barnardo’s: information for enquirers B.E23 Manorial documents register B.E22 “Cave man added to family tree”, cutting 1997 B.E21 Ministry of Defence: application for information from army service records, 1994 B.E20 What to do with the body: some Victorian solutions, extract from Family Tree Magazine, 1995 B.E19 Soldiers: snippets from Peoples England. -

Quarterly Report

1. GOVERNANCE Pārongo ā-Tāone We want to maintain confidence in our decision-making. We have an obligation to ensure the views of Māori and mana whenua are heard. WHAT WE DO • Governance, information and engagement • Māori and mana whenua partnerships. HIGHLIGHTS OF THIS QUARTER • We equipped the council meetings rooms to enable elected members and the public to participate remotely in meetings via audio and audio-visual links. • We interacted with over 78,000 customers through the Contact Centre. • We co-hosted with Port Nicholson Block Settlement Trust, the Waitangi Day celebrations at Waitangi Park. • The Mayor selected her Tuia Rangatahi (Young Māori Leadership Development Programme) representative - Māia Huriwaka, a Year 13 student nominated by Wellington East Girls College. • 11 March – we sponsored Te Rā Haka where 400 college students from across the region came together at ASB Sports Centre to learn local haka. • 15 March – we sponsored Te Rā o Kupe, which was hosted by The Kupe Charitable Trust, recognising local Māori music and food. SIGNIFICANT VARIANCES TO PERFORMANCE1: SERVICE DELIVERY Measure Actual Target Var Variance explanation Council, committee and 61% 80% (24%) Over 80% of agendas were with the elected members five days subcommittee reports that are made before meeting and in the public domain four days before the available to the public five days prior meeting. We continue to achieve 100% for our statutory target to to the meeting (%) make reports available to the public two days prior to meetings. NET OPERATING EXPENDITURE YTD Full Year Activity Actual Budget Variance Forecast Budget $000 $000 $000 $000 $000 1.1 Governance, Information & Engagement 10,444 10,669 224 14,057 14,213 1.2 Māori Engagement (mana whenua) 99 169 70 225 225 Year to date variance is due to timing of MOU payments. -

SS Schedule Release P3

SCHEDULE 201718 DECEMBER 2017 DATE FIXTURE TIME VENUE Wed 13 Auckland Aces V Central Stags 4.00 PM Eden Park no. 2 Auckland Thur 14 Canterbury Kings V Otago Volts 4.00 PM Hagley Oval, Christchurch Fri 15 Knights V Wellington Firebirds 7.00 PM Seddon Park, Hamilton Sat 16 Knights V Auckland Aces 7.00 PM Bay Oval, Mt Maunganui Sun 17 Central Stags V Canterbury Kings 2.00 PM Saxton Oval, Nelson Sun 17 Otago Volts V Wellington Firebirds 4.00 PM University of Otago Oval, Dunedin Wed 20 Wellington FIrebirds V Knights 4.00 PM Basin Reserve, Wellington Fri 22 Canterbury Kings V Central Stags 3.00 PM Mainpower Oval, Rangiora Sat 23 Knights V Otago Volts 2.00 PM Seddon Park, Hamilton Sun 24 Auckland Aces V Wellington Firebirds 3.00 PM Eden Park no. 2, Auckland Tues 26 Wellington Firebirds V Auckland Aces 4.00 PM Basin Reserve, Wellington Tues 26 Otago Volts V Canterbury Kings 4.00 PM Molyneux Park, Alexandra Wed 27 Knights V Central Stags 7.00 PM Bay Oval, Mt Maunganui Thur 28 Otago Volts V Auckland Aces 2.00 PM Molyneux Park, Alexandra Thur 28 Wellington Firebirds V Canterbury Kings 4.00 PM Basin Reserve, Wellington Sat 30 Central Stags V Knights 4.00 PM Pukekura Park, New Plymouth Sun 31 Wellington Firebirds V Otago Volts 4.00 PM Basin Reserve, Wellington JANUARY 2018 DATE FIXTURE TIME VENUE Mon 01 Canterbury Kings V Auckland Aces 3.00 PM Hagley Oval, Christchurch Tue 02 Otago Volts V Knights 4.00 PM University of Otago Oval, Dunedin Thur 04 Central Stags V Auckland Aces 4.00 PM Pukekura Park, New Plymouth Fri 05 Canterbury Kings V Knights 4.00 PM Hagley Oval, Christchurch Sat 06 Central Stags V Otago Volts 4.00 PM Pukekura Park, New Plymouth Sun 07 Auckland Aces V Knights 4.00 PM Eden Park no. -

Sustainable Transport Committee 5 December 2018, Order Paper - Front Page

Sustainable Transport Committee 5 December 2018, Order Paper - Front Page If calling please ask for: Democratic Services 30 November 2018 Sustainable Transport Committee Order Paper for the meeting of the Sustainable Transport Committee to be held in the Council Chamber, Greater Wellington Regional Council, Level 2, 15 Walter Street, Te Aro, Wellington Wednesday, 5 December 2018 at 9.30am Membership Cr Donaldson (Chair) Cr Ponter (Deputy Chair) Cr Blakeley Cr Brash Cr Gaylor Cr Kedgley Cr Laban Cr Laidlaw Cr Lamason Cr McKinnon Cr Ogden Cr Staples Cr Swain Marama Tuuta Recommendations in reports are not to be construed as Council policy until adopted by Council 1 Sustainable Transport Committee 5 December 2018, Order Paper - Agenda Sustainable Transport Committee Order Paper for the meeting to be held on Wednesday, 5 December 2018 in the Council Chamber, Greater Wellington Regional Council, Level 2, 15 Walter Street, Te Aro, Wellington at 9.30am Public Business Page No. 1. Apologies 2. Declarations of conflict of interest 3. Public participation 4. Confirmation of the Public minutes of 30 October Report 18.517 3 2018 5. Action items from previous Sustainable Transport Report 18.529 11 Committee meetings 6. Implementation of new Wellington bus network – Report 18.526 14 December update 7. General Managers' report to the Sustainable Report 18.525 50 Transport Committee meeting on 5 December 2018 8. Exclusion of the public Report 18.575 56 Public Excluded Business 9. Confirmation of the Public Excluded minutes of Report PE18.518 57 30 October -

Global-Research-Summary-Report.Pdf

Summary Report LET’S GET WELLINGTON MOVING This report presents summary findings of the Let’s Get Wellington Moving (LGWM) November and December 2017 public engagement. February 2018 Report prepared by Global Research Ltd Report By Global Research Ltd Foreword by Let’s Get Wellington Moving Let’s Get Wellington Moving (LGWM) is a joint initiative between Wellington City Council, Greater Wellington Regional Council, and the New Zealand Transport Agency. We’re working with the people of Wellington to develop a transport system that improves how the city looks, feels, and functions. Our focus is the area from Ngauranga to the airport, including the Wellington Urban Motorway and connections to the central city, port, hospital, and the eastern and southern suburbs. OUR WORK SO FAR In 2016 we talked with people around the region to learn what people like and dislike about Wellington and how they get around the city. Using feedback from more than 10,000 people, we developed a set of urban design and transport priniciples to guide our work. We then collected extensive transport data, and used the principles and ideas from the public to develop scenarios to improve Wellington’s transport and support the city’s growth. THIS REPORT In November and December 2017, we released four scenarios for Wellington’s transport future and promoted these in a region-wide public engagement programme. The scenarios were presented in the document Have Your Say…on Let’s Get Wellington Moving and on the website yourvoice.getwellymoving.co.nz. As a result, LGWM received 1,994 online and hardcopy-form responses, 147 letter/report style responses (including 55 from stakeholder groups), and 35 Facebook posts. -

COMPILATION Report Wellington Public Transport Spine Study

COMPILATION REPORT WELLINGTON PUBLIC TRANSPORT SPINE STUDY CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 9 2. Public Transport in Wellington 15 3. Study Engagement 21 4. Study Approach 25 5. The Problem and Desired State for Public Transport 29 6. Future Development and Transport Trends 33 7. The Options 37 8. The Option Results 59 9. Staging of options 71 10. Supporting Policy Interventions 75 11. Treasury Better Business Case 79 12. Conclusion 89 Appendix A International Review Case Studies 91 Appendix B Mode Description and Application 93 Appendix C Option Costs 99 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 | Compilation Report | Wellington Public Transport Spine Study Background The process The Public Transport Spine Study (PTSS) is The PTSS approach has progressively narrowed about determining what a future public transport down the number of options (long list, medium solution for Wellington might be. The study list, short list), with each stage providing a more was commissioned by Greater Wellington detailed analysis of those options. Regional Council, Wellington City Council and the New Zealand Transport Agency. These The option assessment was underpinned by three agencies have worked in partnership findings from an international review of public throughout this study to ensure it is aligned transport systems which informed the study of with the economic and transport needs in the characteristics of different transport modes, Wellington City and the wider region. success factors, design issues, constraints, available technology and procurement processes. A key action from the Ngauranga to Airport Corridor Plan (2008) was to provide major improvements to Transport modelling, using a suite of regional public transport to provide a high quality, reliable models and the latest land use and transport and safe service between the Wellington Rail forecasts, has informed the assessment, along with Station and the regional hospital. -

Basin Reserve Heritage Backgrounder

SAVE THE BASIN RESERVE NO FLYOVER www.savethebasin.org.nz [email protected] Basin Reserve Heritage Introduction The Basin Reserve is one of Wellington’s most significant reserves and recreation areas. It is registered as an ‘Historic Area’ by the NZ Historic Places Trust – the first sports ground in New Zealand to receive this. All parts, including the Museum Stand (Pavilion), R.A. Vance Stand, Groundman's Shed, playing oval and picket fence, Reid and Dempster Gates, former Midland St Pats Cricket Clubrooms, the main fence, William Wakefield Fountain, toilets, scoreboard, play area, three light towers and the bank, are included in the registration. In addition, the Pavilion has a Category 2 registration. Earliest days The area occupied by the Basin Reserve was once a lagoon connected to the harbour by a stream, bordered by swamp. It was called the Basin by William Mein Smith, the Surveyor General in 1840, because he envisaged that, as the settlement grew, the stream could be widened and barges could be drawn up to a Basin created there. From surrounding warehouses, goods would be efficiently distributed to the city and Newtown. Mein Smith’s plans for a canal and dock were put paid to by a very large earthquake in 1855. At 8.2 on the richter scale, it raised Te Aro Flat 5 feet so the lagoon became a mere swamp. Gift to the people of Wellington The citizens of Wellington own the Basin Reserve. The land was first granted by the Crown in 1861 “in trust for the purposes of public utility to the Town of Wellington and its inhabitants”. -

Wai 2200, #4.1.10

Wai 2200, #4.1.10 WAI 2200 - NGA KORERO TUKU IHO HELD AT WHAKARONGOTAI MARAE WAIKANAE 22 APRIL 2015 Tribunal: Deputy Chief Judge C Fox Emeritus Professor Sir Tamati Reedy Dr Grant Phillipson Honourable Sir Douglas Kidd Tania Simpson Crown Counsel: Ashleigh Allan Ellen Chapple Jacki Cole Wiremu (Bill) Kaua (Kaumātua) Claimant Speakers: Paora Ropata Snr (In speaking order) Hepa Potini Paora Ropata Jnr Rawhiti Higgott Hauangi Kiwha Queenie Rikihana Hyland Jim Webber Chris Webber Yvonne Mitchell Albie Ellison Mahutonga Blankensop Mahina-a-rangi Baker Miria Pomare Ngapera Parata Ani Parata, Karen Parata and Darrin Parata Hepa Potini 1 TABLE OF SPEAKERS (09:54) PAORA ROPATA SNR: (WAI 1945) .......................................................................................... 9 (10:31) HEPA POTINI: (WAI 88 AND 89) ............................................................................................. 31 (11:16) PAORA TEMUERA RŌPATA JNR: (RŌPATA WHĀNAU) ..................................................... 54 HEARING ADJOURNS: 12.04 PM ..................................................................................................... 73 (12:46) RAWHITI HIGGOTT: (TE ĀTI AWA / NGĀTI AWA) ................................................................. 74 (13:30) HAUANGI KIWHA: (PARATA WHĀNAU) ................................................................................ 99 (13:50) KUINI RIKIHANA: (PARATA WHĀNAU) ............................................................................... 108 (14:01) JIM WEBBER: (KAPITI ISLAND)