Practicum 2003 Heritage Inventory Wellington Botanic Garden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wellington Town Belt Management Plan – June 2013 49

6 Recreation The play area at Central Park, Brooklyn. A flying fox and bike skills area are also provided. Guiding principles The Town Belt is for all to enjoy. This concerns equity of access and use of the Town Belt. The Council believes that the Town Belt should be available for all Wellingtonians to enjoy. The Council is committed to ensuring that the Town Belt will continue to be improved with more access and improved accessibly features where it is reasonably practicable to do so. The Town Belt will be used for a wide range of recreation activities. The Town Belt should cater for a wide range of sporting and recreation activities managed in a way to minimise conflict between different users. Co-location and intensification of sports facilities within existing hubs and buildings is supported where appropriate. 6.1 Objectives 6.1.1 The Town Belt is accessed and used by the community for a wide range of sporting and recreational activities. 6.1.2 Recreational and sporting activities are environmentally, financially and socially sustainable. 6.1.3 Participation in sport and recreation is encouraged and supported. 6.1.4 The Town Belt makes a significant contribution to the quality of life, health and wellbeing of Wellingtonians by increasing a range of physical activity and providing active transport routes and access to natural environments 6.1.5 The track (open-space access) network provides for a range of user interests, skills, abilities and fitness levels, and pedestrian and cycling commuter links. 6.1.6 Management and development of formal sporting facilities and associated infrastructure does not compromise the landscape and ecological values of the Town Belt. -

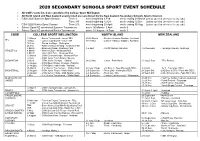

2020 Secondary Schools Sport Event Schedule

2020 SECONDARY SCHOOLS SPORT EVENT SCHEDULE All CSW events listed are sanctioned by College Sport Wellington All North Island and New Zealand events listed are sanctioned by the New Zealand Secondary Schools Sports Council. CSW 2020 Summer Sport Season: Term 1: week beginning 3 Feb week ending 29 March [unless specified otherwise for any code] Term 3/4: week beginning 12 Oct week ending 12 Dec [unless specified otherwise for any code] CSW 2020 Winter Sport Season: Term 2/3: week beginning 28 April week ending 30 Aug [unless specified otherwise for any code] School Sport NZ sanctioned Summer Tournament week: 30 March - 3 April week 9 School Sport NZ sanctioned Winter Tournament week: 31 August - 4 Sept week 7 CODE COLLEGE SPORT WELLINGTON NORTH ISLAND NEW ZEALAND 19 March - Senior Tournament - venue TBA 25-26 March - Seniors -Harbour Stadium, Auckland AFL 10 Nov - Junior Tournament - venue TBA 18-19 Nov - Juniors -Harbour Stadium, Auckland 16 Feb - Round the Bays - Wellington 25 Feb - AWD selection Meeting - Newtown Park 3 March - McEvedy Shield - Newtown Park 3-5 April - Porritt Stadium, Hamilton 4-6 December - Tauranga Domain, Tauranga ATHLETICS 4 March - Western Zone - Newtown Park 5 March - Hutt / Girls Zone - Newtown Park 12 March - CSW Championships - Newtown Park 23 July - CSW Junior Team Finals - Naenae BADMINTON 29 July - CSW Junior Champs - Haitaitai 24-26 Nov - Junior - Palm North 31 Aug-3 Sept - TRA, Porirua 12 August - CSW Open Singles Champs - Haitaitai 21 August - CSW Open Team Finals - Haitaitai 26 March - 3 x 3 Senior -

Section Ii: Other Items

SECTION II: OTHER ITEMS II.i Contents of Miscellaneous Folders II.i.a Britain: Miscellaneous Folder B.E England B.E40 “Society of Brushmakers’ Descendants, Members’ Interest Names, 1997”. B.E39 “How names are in our genes” Observer, Feb. 2001. B.E38 “Update on Places in London [central] Where Records are Located” from Richard Moore. Also “English Poor Laws”, brief notes (incl. list of recommended reading) from Marjorie R. Moore, Jul 2000. 2 pp. B.E37 Family Records, Centre, 1 Myddelton St, London (flyer) B.E36 NORCAP News no.53, 1998 (Nat.Org.for Counselling of Adoptees & Parents) B.E35 Access to Birth Records: counselling organisations outside the United Kingdom; and Access to Birth Records: Information for adopted people living outside the United Kingdom, Office of National Statistics B.E34 Addresses for Genealogical Research in Great Britain & Eire B.E33 Roll of Battle Abbey, A.D. 1066 B.E32 “The modern way to trace your family tree”, from Woman’s Weekly, 1999. B.E31 Review of Anthony Camp talk on occupations in towns, with extensive bibliography B.E30 St Catherines House Indexes - volume nos. by counties, 1992 B.E29 Record repositories, extract from Family Tree Magazine 1996 B.E28 Extract from London Street Directory 1852, & 1854 (2 pp only) B.E27 The modern British army cap badge: a brief guide as to how it evolved, compiled by John McConaghy. 9 pp. B.E26 Research material available to the genealogist in the UK & Europe B.E25 British & Irish Biographies 1840-1940, review B.E24 Barnardo’s: information for enquirers B.E23 Manorial documents register B.E22 “Cave man added to family tree”, cutting 1997 B.E21 Ministry of Defence: application for information from army service records, 1994 B.E20 What to do with the body: some Victorian solutions, extract from Family Tree Magazine, 1995 B.E19 Soldiers: snippets from Peoples England. -

Quarterly Report

1. GOVERNANCE Pārongo ā-Tāone We want to maintain confidence in our decision-making. We have an obligation to ensure the views of Māori and mana whenua are heard. WHAT WE DO • Governance, information and engagement • Māori and mana whenua partnerships. HIGHLIGHTS OF THIS QUARTER • We equipped the council meetings rooms to enable elected members and the public to participate remotely in meetings via audio and audio-visual links. • We interacted with over 78,000 customers through the Contact Centre. • We co-hosted with Port Nicholson Block Settlement Trust, the Waitangi Day celebrations at Waitangi Park. • The Mayor selected her Tuia Rangatahi (Young Māori Leadership Development Programme) representative - Māia Huriwaka, a Year 13 student nominated by Wellington East Girls College. • 11 March – we sponsored Te Rā Haka where 400 college students from across the region came together at ASB Sports Centre to learn local haka. • 15 March – we sponsored Te Rā o Kupe, which was hosted by The Kupe Charitable Trust, recognising local Māori music and food. SIGNIFICANT VARIANCES TO PERFORMANCE1: SERVICE DELIVERY Measure Actual Target Var Variance explanation Council, committee and 61% 80% (24%) Over 80% of agendas were with the elected members five days subcommittee reports that are made before meeting and in the public domain four days before the available to the public five days prior meeting. We continue to achieve 100% for our statutory target to to the meeting (%) make reports available to the public two days prior to meetings. NET OPERATING EXPENDITURE YTD Full Year Activity Actual Budget Variance Forecast Budget $000 $000 $000 $000 $000 1.1 Governance, Information & Engagement 10,444 10,669 224 14,057 14,213 1.2 Māori Engagement (mana whenua) 99 169 70 225 225 Year to date variance is due to timing of MOU payments. -

Sustainable Transport Committee 5 December 2018, Order Paper - Front Page

Sustainable Transport Committee 5 December 2018, Order Paper - Front Page If calling please ask for: Democratic Services 30 November 2018 Sustainable Transport Committee Order Paper for the meeting of the Sustainable Transport Committee to be held in the Council Chamber, Greater Wellington Regional Council, Level 2, 15 Walter Street, Te Aro, Wellington Wednesday, 5 December 2018 at 9.30am Membership Cr Donaldson (Chair) Cr Ponter (Deputy Chair) Cr Blakeley Cr Brash Cr Gaylor Cr Kedgley Cr Laban Cr Laidlaw Cr Lamason Cr McKinnon Cr Ogden Cr Staples Cr Swain Marama Tuuta Recommendations in reports are not to be construed as Council policy until adopted by Council 1 Sustainable Transport Committee 5 December 2018, Order Paper - Agenda Sustainable Transport Committee Order Paper for the meeting to be held on Wednesday, 5 December 2018 in the Council Chamber, Greater Wellington Regional Council, Level 2, 15 Walter Street, Te Aro, Wellington at 9.30am Public Business Page No. 1. Apologies 2. Declarations of conflict of interest 3. Public participation 4. Confirmation of the Public minutes of 30 October Report 18.517 3 2018 5. Action items from previous Sustainable Transport Report 18.529 11 Committee meetings 6. Implementation of new Wellington bus network – Report 18.526 14 December update 7. General Managers' report to the Sustainable Report 18.525 50 Transport Committee meeting on 5 December 2018 8. Exclusion of the public Report 18.575 56 Public Excluded Business 9. Confirmation of the Public Excluded minutes of Report PE18.518 57 30 October -

Soldiers and School Children Military Performances and National Identity During the Prince of Wales’ 1920 Visit to Wellington

UHPH_14: Landscapes and ecologies of urban and planning history | 463 Soldiers and School Children Military performances and national identity during the Prince of Wales’ 1920 visit to Wellington Christopher McDonald Victoria University of Wellington/University of New South Wales [email protected] Early royal visits to New Zealand were episodes of intense symbolic activity played out on an urban scale. These events are generally understood as affirmations of British identity. However, this paper shows how the Prince of Wales’ 1920 tour of New Zealand was also used to promote the distinct character of the young dominion. The research examines two military performances in Wellington: a review at Newtown Park and a quasi-military parade of school children in parliament grounds. Analysis of these events reveals dual narratives in which New Zealanders both reaffirm their links with the Motherland and acknowledge their own difference. The two sources of identity are found to be compatible but dependent on malleable images. The paper argues that military images and narratives were flexible enough to convey New Zealanders’ “imperial” and “national” allegiances. However, while a dual narrative operated successfully during the “Children’s Day” display, the more conventional military review at Newtown Park failed because it was unable to reconcile the antipodean traits of discipline and vigour. Both performances required a degree of improvisation because Wellington lacked dedicated sites for military ceremonial. The choice of venues contributed to the disparate outcomes of the two events. In parliament grounds, school groups exhibited the health and dynamism of New Zealand’s youth but also reinforced the latent order and unity of New Zealand’s pre-eminent “national” space. -

2019 College Sport Disability Programme Proudly Supported By

2019 College Sport Disability Programme Proudly supported by: Para Sport Events (Students participating must have, or be working towards a Para Classification) Term 1 Begins 28 January o CSW Zone Athletics (Disabled Athletes) Newtown Park 26 February (Championship Events) o Wairarapa Inter-Collegiate Athletics Pelorus Trust Athletics Track 28 February o McEvedy Shield Athletics Newtown Park 5 March o Western Zone Athletics Newtown Park 6 March o Hutt/Girls Zone Athletics Newtown Park 7 March o CSW Regional Athletics Champs Newtown Park 14 March o North Island Schools Athletics Tauranga 6-7 April Term 2 Begins 29 April o North Island Schools Swimming Palmerston North 11 May o CSW Individual Swimming Champs Naenae 4 July o CSW Cross Country Harcourt Park (Upper Hutt) 29 May (12 noon start) Term 3 Begins 22 July o CSW Road Race Champs Trentham Memorial Park 7 August (12.00 noon start) Term 4 Begins 14 October o NZ Secondary School Athletics incl. Road Race Newtown Park, Wellington 6 to 8 December Active Recreation Sport Events (Events are open to all students with a disability) Term 1 Begins 28 January o CSW Zone Athletics (Disabled Athletes) Newtown Park 26 Feb (9.30am report – (Non-Championship Events) 2.00pm) o Teeball Fraser Park 26 Mar (10am – 1pm) o Rippa Rugby Mana College 10 Apr (10am-1pm) Term 2 Begins 29 April o Futsal - 5 week league Hutt Indoor Sports Weds 8 May-12 June (10am-12noon, excl. 29 May – X Country) o CSW Cross Country Harcourt Park (Upper Hutt) 29 May (12 noon start) o Ten Pin Bowlarama 3 July (10am-1pm) Term 3 Begins 22 July o CSW Road Race Champs Trentham Memorial Park 7 August (12.00 noon start) o Basketball – 4 week league Te Rauparaha Arena Weds 31 Jul to 28 Aug (10 – 12.00), excl. -

Building Name

Date: 10 December 2013 Botanic Gardens Main Gates and Fence Glenmore Street Image: Googlemaps 2013 Summary of heritage significance • The Botanic Gardens Main Gates are a particularly fine set of Victorian gates and are notable for the quality of their design, materials and workmanship. • These gates are primarily associated with the establishment of the Botanic Gardens which is an area of considerable historic, cultural, and heritage value. The Gardens are associated with a number of important and influential Wellingtonians and New Zealanders. In particular the gates are associated with J.G. MacKenzie the Director of Parks and Gardens who oversaw their construction. The Gates are also associated with the Hospital and the Hospital Board who owned them prior to their installation at the Gardens. • The Botanic Gardens Gates and Fence have an enduring social value as the main entrance to the Botanic Garden, an extremely popular public space in Wellington city. This connection remains today as the Gardens are well patronised throughout the year. 1 Date: 10 December 2013 District Plan: Map 17, reference 17 Legal Description: Pt Lot 1 DP 8530 Heritage Area: Wellington Botanic Gardens Heritage Area HPT Listed: Historic Area, reference 7573 Archaeological Site: Risk Unknown Other Names: - Key physical dates: c. 1878, alterations c.1925 Architect / Builder: City Engineer, Builder: Messrs Hickmott and Sons Former uses: Civic – gates and fence Current uses: Civic – gates and fence Earthquake Prone Status: Unknown at time of writing Extent: Cityview GIS 2013 2 Date: 10 December 2013 1.0 Outline History 1.1 History1 The Founders’ entrance has always been the main entrance to the Wellington Botanic Garden, although it has not always been in the form that it is today. -

Draft Town Belt Management Plan

DRAFT TOWN BELT MANAGEMENT PLAN October 2012 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Town Belt concept 1 1.2 What is the Wellington Town Belt? 2 1.3 The Town Belt Management Plan 2 1.3.1 Coverage of the plan 5 1.4 Achievements of the 1995 Town Belt Management Plan 7 1.5 Other relevant policies and plans 8 2 Town Belt legislative and policy framework 12 2.1 How is the Town Belt managed? 12 2.2 Town Belt principles 13 2.3 Town Belt legal status 15 2.4 Town Belt alienations 16 2.5 Reinstatement Policy in the 1995 Management Plan and 1998 Reinstatement Policy 17 2.6 The Port Nicholson Block (Taranaki Whānui ki Te Upoko o Te Ika) Claims Settlement Act 2009 17 2.7 Proposed approach to Town Belt additions 18 2.8 Objective 19 2.9 Policies 19 3 Partnership and community participation 21 3.1 Partnership with mana whenua 21 3.1.1 Objective 23 3.1.2 Policies 23 3.2 Community participation 23 3.2.1 Objective 24 3.2.2 Policies 24 4. Landscape 25 4.1 The Town Belt landscape 25 4.1.1 Wellington’s landscape character 25 4.1.2 Town Belt landscape change 26 4.1.3 The Town Belt landscape today 28 4.2 Objectives 30 4.3 Policies 31 5 Ecology 33 5.1 Historic ecosystems 33 5.2 Current ecological values 34 5.3 Issues and opportunities 35 5.3.1 Restoration 35 5.3.2 Pest management 35 5.3.3 Carbon management 38 5.4 Objectives 38 5.5 Policies 39 Draft Town Belt Management Plan October 2012 6 Recreation 41 6.1 Recreational role of Town Belt 41 6.2 What is recreation? 42 6.3 Existing recreational activities 43 6.4 Sporting infrastructure 43 6.5 Objectives 52 6.6 Policies -

Slice of Heaven Exhibition Credits

SLICE OF HEAVEN: 20TH CENTURY AOTEAROA FILMS The credits below are arranged according to the section of Slice of Heaven in which they appear. International relations: Mother country Little Britain FILM Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga The Years Back (1) The Twentieth Century, 1973. National Film Unit, New Zealand (BITC 264) From material preserved and made available by The New Zealand Film Archive Ngā Kaitiaki o ngā Taonga Whitiāhua Royal visit of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York to New Zealand, 1901. Limelight Department, Salvation Army (F2464) Floral and garden fete at Oamaru, 1912. New Zealand Tourist Department (F7548) Scenes at the New Zealand Exhibition, 1906. T J West (F2656) Auckland Cup, 1912 (F10454) Dominion Day celebrations, Newtown Park, Wellington, 1908. Department of Tourism, New Zealand Government (F8277) Dominion Day celebrations, Basin Reserve, Wellington, 1908. Department of Tourism, New Zealand Government (F8276) Topical budget: His Majesty the King inspects ‘The New Zealand’ at Portsmouth, 1913. Used with permission of the BFI National Archive, England (F29375) New Zealand leads the way, scenes on-board HMS New Zealand, Britannia rules the waves, 1913. Jury’s Imperial Pictures (F4387) Auckland’s reception to the battleship HMS New Zealand, 1913. New Zealand Government (F10484) Excerpt in the recording of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession, 1897. R W Paul, England (F11225) STILL IMAGES Alexander Turnbull Library, Photograph & Newspaper Collections National Library of New Zealand -

Minutes NRA Oct 2014

Minutes of the Newtown Residents’ Association Meeting October 20th 2014 Present Claire Pettigrew (Chair), Ken Allen, Rhona Carson, Mark Coburn, Carol Comber, Peter Cooke, Steve Cosgrove, James Coyle, Steve Dunn, Paul Eagle, Peter Frater, Tom Law, Kevin Lethbridge, Martin Hanley, Anna Kemble Welch, Jeanie McCafferty, Don McDonald, Don Mackay, Patrick Morgan, Laura Newcombe, Stephen Pritchard, Efffie Rankin, Cheryl Robilliard, Michael Scott, Jonathon Sharp, Dave Smyth, Andrew Turquet, Ralph Wilkinson, Kate Zwartz. Apology – Celia Wade-Brown 1. What is happening around the Basin Reserve? • A brief report and discussion of the appeal the New Zealand Transport Agency is taking to the High Court against the decision to decline the Basin Flyover proposal. Save the Basin and the Architecture Centre are fundraising for the legal costs of being represented at the hearing. There is no date for this yet. • Martin was the NRA representative at a meeting called by Grant Robertson to discuss next steps of the development of transport solutions for Wellington, in particular in the area around the Basin Reserve. Martin had some plans for suggested changes to traffic and bus lanes leading off Kent Tce that the Urban Activation Lab has been working on, and had copies to show tonight’s meeting. • Outcomes of Grant’s meeting − A letter to the Mayor, NZTA and Regional Council, to be signed by a wide range of community groups, asking for more community involvement with the development of plans for the Ngauranga to Airport corridor. Mt Cook Mobilised have suggested some wording changes to be less adversarial, these are being incorporated. − A follow-up meeting with the Regional Council on Friday Oct 24th. -

Journal Issue # 137

OCT 2014 JOURNAL ISSUE # 137 PUBLISHED BY FEDERATION OF RAIL ORGANISATIONS NZ INC : P O BOX 140, DUNEDIN 9054 PLEASE SEND CONTRIBUTIONS TO EDITOR, SCOTT OSMOND, BY E-MAIL : [email protected] FRONZ Boiler Inspection Review 1 Wanganui Modes Meet 4 Napier Gisborne Railway Website 1 Digital Forum Conference 4 IN THIS ISSUE Editor’s Holiday 1 Member’s Classifieds 4 COTMA Conference 2 News From Our Members 5 DSC Loco Thoughts 2 Photo of the Month 11 Christchurch Icefest 3 FRONZ BOILER INSPECTION REVIEW Following from the FRONZ Conference decision to follow up contracting Peter George of Sentinel Inspection Services Ltd to update our member's boiler inspection code and get it officially recognised. The aim of the review of the Code is to: 1. Update and reformat the Code as needed so that it can be accepted (probably as approved guidance ma- terial rather than as a Code in its own right) by the relevant government agencies and the boiler inspection industry. 2. Provide guidance on acceptable levels of inspection (i.e. how often, what to look for, and how to look for it). 3. Provide guidance on acceptable repair methods for typical locomotive boiler defects. Peter has advised he is prepared to undertake the work which would include: Formatting Code Information on Inspection Materials and Repair Guidance Updating material specifications Liaison with interested parties (especially all the major railway operating groups as we must have their buy in). NZTA are still keen to support the work and WorkSafe are also keen to see this progressed. FRONZ is seeking best options for funding this work.