Fall Hawkwatching: When & Where. a Guide to the Best Times and Sites in Our Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town of Temple, New Hampshire Planning Board

TOWN OF TEMPLE, NEW HAMPSHIRE PLANNING BOARD NOVEMBER 30, 2011 FINAL MINUTES OF PUBLIC MEETING Board members present: John Kieley, Randy Martin, Bruce Kullgren, Allan Pickman, Richard Whitcomb, and Rose Lowry Call to order by Pickman at 7:20 p.m. after a slight delay in setting up the PowerPoint presentation. Public forum on Large Wind Energy Systems: Lowry welcomed the audience of approximately 60 people and gave an overview of the meeting format. She asked that questions be held until after the initial presentation. Lowry then provided commentary to a PowerPoint display. She explained that Pioneer Green Energy has proposed a multi-tower wind farm project in the neighboring town of New Ipswich, and is also considering placement of 1 to 3 towers in Temple in the area of Kidder Mountain. She indicated planning is still in the preliminary stages. She said Temple is considered an abutter to the New Ipswich project due to regional impact. Even if no turbines are installed in Temple, all New Ipswich towers would be visible in Temple. Lowry stated New Ipswich already has a large wind energy zoning ordinance in place to regulate commercial wind, and now Temple is considering creation of such an ordinance. This would help maintain local control, protect the character of the town, safeguard public health and safety, preserve property values, and protect wildlife and the environment. She also said without any local control the state Site Evaluation Committee (SEC) could become involved, as well as the local Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA). Lowry next discussed turbine size and the amount of energy created. -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

Birds of Mt. Philo State Park

Sp Su F W Sp Su F W __ Tree Swallow c u c - __ Magnolia Warbler c r c - Birds __ Barn Swallow u u u - __ Bay-breasted Warbler r - u - Chickadees and Titmice __ Blackburnian Warbler* c u c - __ Black-capped Chickadee* c c c c __ Chestnut-sided Warbler* c c c - of Mt. Philo __ Tufted Titmouse* c c c c __ Blackpoll Warbler u - c - Nuthatches __ Black-throated Blue Warbler* c c c - State Park __ Red-breasted Nuthatch* u u u r __ Pine Warbler* u u u - __ White-breasted Nuthatch* c c c c __ Yellow-rumped Warbler c r c - M Creepers __ Black-throated Green Warbler c r c - t __ Brown Creeper* u u u u __ Canada Warbler* u r u - . Wrens Sparrows P __ Winter Wren* c c c - __ Eastern Towhee* c c c - h Kinglets __ Chipping Sparrow* c c c - i __ Golden-crowned Kinglet c - c - __ Field Sparrow r r r - l __ Ruby-crowned Kinglet c - c - __ Savannah Sparrow r r r - o Thrushes __ Song Sparrow* c c c - S __ Veery* c c c - __ White-throated Sparrow c - c - t __ Swainson's Thrush u - u - __ Dark-eyed Junco* u u u - a __ Hermit Thrush* c c c - Cardinals and Relatives t e __ Wood Thrush* c c c - __ Scarlet Tanager* c c c - __ American Robin* c c c r __ Northern Cardinal* c c c c P Waxwings __ Rose-breasted Grosbeak* c c c - a __ Bohemian Waxwing r - - r __ Indigo Bunting* u u u - r Mt. -

State of New Hampshire

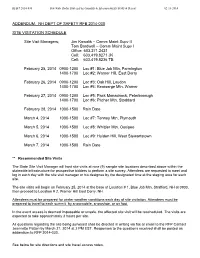

RFB # 2014-030 Statewide Radio System Functionality & Interoperability Study & Report 02-10-2014 ADDENDUM. NH DEPT OF SAFETY RFB 2014-030 SITE VISITATION SCHEDULE Site Visit Managers; Jim Kowalik – Comm Maint Supv II Tom Bardwell – Comm Maint Supv I Office: 603.271.2421 Cell: 603.419.8271 JK Cell: 603.419.8236 TB February 25, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #1: Blue Job Mtn, Farmington 1400-1700 Loc #2: Warner Hill, East Derry February 26, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #3: Oak Hill, Loudon 1400-1700 Loc #4: Kearsarge Mtn, Warner February 27, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #5: Pack Monadnock, Peterborough 1400-1700 Loc #6: Pitcher Mtn, Stoddard February 28, 2014 1000-1500 Rain Date March 4, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #7: Tenney Mtn, Plymouth March 5, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #8: Whittier Mtn, Ossipee March 6, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #9: Holden Hill, West Stewartstown March 7, 2014 1000-1500 Rain Date ** Recommended Site Visits The State Site Visit Manager will host site visits at nine (9) sample site locations described above within the statewide infrastructure for prospective bidders to perform a site survey. Attendees are requested to meet and log in each day with the site visit manager or his designee by the designated time at the staging area for each site. The site visits will begin on February 25, 2014 at the base of Location # 1, Blue Job Mtn, Strafford, NH at 0900, then proceed to Location # 2, Warner Hill East Derry, NH. Attendees must be prepared for winter weather conditions each day of site visitation. Attendees must be prepared to travel to each summit by snowmobile, snowshoe, or on foot. -

December 15, 2020, Volume 18, Number 12 Member Spotlight

MassLand E-News The Newsletter of the Massachusetts Land Conservation Community December 15, 2020, Volume 18, Number 12 Member Spotlight Saving an Iconic Landscape North County Land Trust has a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to protect 200 acres including the south peak of Mt. Watatic. Mt. Watatic is a 1,832-foot monadnock just south of the Massachusetts– New Hampshire border, at the southern end of the Wapack Range of mountains. It lies within Ashburnham and Ashby, in Massachusetts, and New Ipswich in New Hampshire. It’s the terminus for the 22-mile Wapack Trail (heading north into NH) and the 92-mile Midstate Trail (heading south to CT). This parcel is part of a quilt of iconic landscapes and provides a critical addition to an unfragmented block of natural habitat. It would complete preservation of the entire summit of the popular Mt. Watatic. NCLT is working in partnership with the Department Fish and Game, as this property has been on the region’s radar as a key property of conservation interest for decades due to its high conservation and recreational value. Learn more. Or contact NCLT with questions at [email protected] or 978-466-3900. Here's your opportunity to highlight a project in the works, or a current conservation success story! Send a short description and a photo to [email protected]. We'd like to highlight properties in various parts of the state, so if we don't get to you this month, we will soon. If you'd like to support MLTC's efforts to educate, connect, and advocate for the Massachusetts land conservation community, please consider making a monthly or one-time tax-deductible donation Thank you! Donate MassLand News What a pleasure to join Groundwork Lawrence in November for a tour of the Ferrous Site, a beautiful 7.5 acre woodland and meadow created on post-industrial land at the historic and scenic confluence of Lawrence's North Canal and the Spicket and Merrimack Rivers. -

News from the Selectboard Labor Day, Monday September

Volume 9 Published monthly since May 1999 September 2015 News from the Selectboard Erik Spitzbarth, Chairman for the Selectboard APPOINTMENTS AND RECOGNITIONS: The BOS approved the following appointments: WHAT HAPPENED TO THE WATER in Norway Pond Contoocook River Advisory – Kenneth Messina, is a science experiment in the making. The self Zoning Board Alternate – Jeff Reder, energizing cynobacteria bloom that was detected relies Cemetery Trustee – Dennis Rossiter (for balance of open on sunlight to drive the process of photosynthesis, 2017 term), absorbing (fixing) CO² and using water as an electron donor that produces oxygen as a byproduct…all essential Historic District Commission – Fred Heyliger, to our well being and life on earth. That being said, we Old Home Days Committee – Melody Russell 3 yr term don’t necessarily want to swim in it. :( The board expresses special appreciation and accolades The town contracts water testing three times during the to the OHD committee, Recreation Committee, Fire De- summer for concentrations of Oscillatoria with the partment, and the many helping hands that volunteered Department of Environmental Services (DES). Our their time and talents in making this year’s “New Life for physical observation of a “bloom” situation initiated an Old Treasures” another success. additional test that confirmed we had approached a “no “KEEPING YOUR HEAD ABOVE WATER” swimming” advisory. Our safe guarding process had gave new meaning to the Synchro Sistahs: worked. For those that want to know more about Adine Aldrich, Alex Murray-Golay, Amy Markus, cynobacteria, search the web or go to the DES website: Barbara Schweigert, Cynthia Nichols, Jan Buonanno, http://des.nh.gov/organization/divisions/water/wmb/ Jess Codman (choreographer),Julie Brown, Lizzy Cohen, beaches/faq_cyanobacteria.htm Sadie Faber, and Tracy Grissom as they performed at the Fake Lake due to Norway Pond’s last minute closing to swimmers! Special kudos go out to the “Sistahs” for continuing their performance and showing us true grit and belief in “the show must go on”. -

Mount Watatic Reservation RMP

Mount Watatic Reservation RMP Mount Watatic Reservation – Resource Management Plan References Ashburnham, Massachusetts. Open Space and Recreation Plan, 2004-2009. Ashby, Massachusetts. Open Space and Recreation Plan, 1999-2004. Clark, Frances (Carex Associates), 1999. Biological Survey of Mt. Watatic Wildlife Management Area and Vicinity. Prepared for Mass. Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Conservation Services. 2000. Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2001. Biomap: Guiding Land Conservation for Biodiversity in Massachusetts. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2003. Living Waters: Guiding the Protection of Freshwater Biodiversity in Massachusetts. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2004. Species Data and Community Stewardship Information. Grifith, G.E., J.M. Omernik, S.M. Pierson, and C.W. Kiilsgaard. 1994. The Massachusetts Ecological Regions Project. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Publication No.17587-74-6/94-DEP. Johnson, Stephen F. 1995. Ninnuock (The People), The Algonquin People of New England. Bliss Publishing, Marlborough, Mass. Massachusetts Invasive Plant Advisory Group. 2005. Strategic Recommendations for Managing Invasive Plants in Massachusetts. -

Birdobserver11.3 Page143-148 New Frontiers in Hawkwatching

NEW FRONTIERS IN HAWKWATCHING: HAWK MIGRATION CONFERENCE IV by H. Christian Floyd, Lexington During March 24-27, 1983, approximately four hundred hawk watching enthusiasts, including leading raptor authorities from the United States, England, Israel, and Panama, gath ered in Rochester, New York, for the presentation of forty papers at Hawk Migration Conference IV, sponsored by the Hawk Migration Association of North America and Hawk Moun tain Sanctuary Association. This report summarizes some of the presentations that were most interesting to me in addressing the frontiers of hawk watching and raptor migration study: the new geographical areas being studied, new efforts to assess the significance of hawkwatching data, and new applications of technology to this area. These summaries just scratch the surface of what was presented at the conference. Having heard all of the presentations first-hand, I am eagerly awaiting the publica tion of the conference proceedings some time next year and hope that this report will lead you to share my anticipation. The western United States is indeed still a frontier with respect to what is known about hawk migration through this region, but much has been learned recently through the ef forts of pioneering hawkwatchers like Steve Hoffman. Ac cording to Steve, only six fall sites in the West receive over one hundred hours of hawkwatching. The relatively low level of hawkwatching activity in the West was explained by four main factors: few birders, difficult access to sites, dispersed migration due to the lack of natural barriers and leading lines, and only recent knowledge of the timing and weather correlations of western flights. -

N.H. State Parks

New Hampshire State Parks WELCOME TO NEW HAMPSHIRE Amenities at a Glance Third Connecticut Lake * Restrooms ** Pets Biking Launch Boat Boating Camping Fishing Hiking Picnicking Swimming Use Winter Deer Mtn. 5 Campground Great North Woods Region N K I H I A E J L M I 3 D e e r M t n . 1 Androscoggin Wayside U U U U Second Connecticut Lake 2 Beaver Brook Falls Wayside U U U U STATE PARKS Connecticut Lakes Headwaters 3 Coleman State Park U U U W U U U U U 4 Working Forest 4 Connecticut Lakes Headwaters Working Forest U U U W U U U U U Escape from the hectic pace of everyday living and enjoy one of First Connecticut Lake Great North Woods 5 Deer Mountain Campground U U U W U U U U U New Hampshire’s State Park properties. Just think: Wherever Riders 3 6 Dixville Notch State Park U U U U you are in New Hampshire, you’re probably no more than an hour Pittsbur g 9 Lake Francis 7 Forest Lake State Park U W U U U U from a New Hampshire State Park property. Our state parks, State Park 8 U W U U U U U U U U U Lake Francis Jericho Mountain State Park historic sites, trails, and waysides are found in a variety of settings, 9 Lake Francis State Park U U U U U U U U U U ranging from the white sand and surf of the Seacoast to the cool 145 10 Milan Hill State Park U U U U U U lakes and ponds inland and the inviting mountains scattered all 11 Mollidgewock State Park U W W W U U U 2 Beaver Brook Falls Wayside over the state. -

Outdoor Recreation Recreation Outdoor Massachusetts the Wildlife

Photos by MassWildlife by Photos Photo © Kindra Clineff massvacation.com mass.gov/massgrown Office of Fishing & Boating Access * = Access to coastal waters A = General Access: Boats and trailer parking B = Fisherman Access: Smaller boats and trailers C = Cartop Access: Small boats, canoes, kayaks D = River Access: Canoes and kayaks Other Massachusetts Outdoor Information Outdoor Massachusetts Other E = Sportfishing Pier: Barrier free fishing area F = Shorefishing Area: Onshore fishing access mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/fba/ Western Massachusetts boundaries and access points. mass.gov/dfw/pond-maps points. access and boundaries BOAT ACCESS SITE TOWN SITE ACCESS then head outdoors with your friends and family! and friends your with outdoors head then publicly accessible ponds providing approximate depths, depths, approximate providing ponds accessible publicly ID# TYPE Conservation & Recreation websites. Make a plan and and plan a Make websites. Recreation & Conservation Ashmere Lake Hinsdale 202 B Pond Maps – Suitable for printing, this is a list of maps to to maps of list a is this printing, for Suitable – Maps Pond Benedict Pond Monterey 15 B Department of Fish & Game and the Department of of Department the and Game & Fish of Department Big Pond Otis 125 B properties and recreational activities, visit the the visit activities, recreational and properties customize and print maps. mass.gov/dfw/wildlife-lands maps. print and customize Center Pond Becket 147 C For interactive maps and information on other other on information and maps interactive For Cheshire Lake Cheshire 210 B displays all MassWildlife properties and allows you to to you allows and properties MassWildlife all displays Cheshire Lake-Farnams Causeway Cheshire 273 F Wildlife Lands Maps – The MassWildlife Lands Viewer Viewer Lands MassWildlife The – Maps Lands Wildlife Cranberry Pond West Stockbridge 233 C Commonwealth’s properties and recreation activities. -

Stol. 12 NO. 2

•‘j \ " - y E ^ tf -jj ^ ^ p j | %A .~.,.. ,.<•;: ,.0v -^~., v:-,’-' ' •'... : .......... ■l:"'-"4.< «S ife.,.. .1 { ‘. , ‘ 'M* m m m m m m m ...y m ;y StoL.W 12 NO. 2 V"-' . :.... .,.■... '..'/.'iff? ' ' kC'"^ ' BIRD OBSERVER OF EASTERN MASSACHUSETTS APRIL 1984 VOL. 12 NO. 2 President Editorial Board Robert H. Stymeist H. Christian Floyd Treasurer Harriet Hoffman Theodore H. Atkinson Wayne R. Petersen Editor Leif J. Robinson Dorothy R. Arvidson Bruce A. Sorrie Martha Vaughan Production Manager Soheil Zendeh Janet L. Heywood Production Subscription Manager James Bird David E. Lange Denise Braunhardt Records Committee Herman H. D’Entremont Ruth P. Emery, Statistician Barbara Phillips Richard A. Forster, Consultant Shirley Young George W. Gove Field Studies Committee Robert H. Stymeist John W. Andrews, Chairman Lee E. Taylor Bird Observer of Eastern Massachusetts (USPS 369-850) A bi-monthly publication Volume 12, No. 2 March-April 1984 $8.50 per calendar year, January - December Articles, photographs, letters-to-the-editor and short field notes are welcomed. All material submitted will be reviewed by the editorial board. Correspondence should be sent to: Bird Observer > 462 Trapelo Road POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: Belmont, MA 02178 All field records for any given month should be sent promptly and not later than the eighth of the following month to Ruth Emery, 225 Belmont Street, Wollaston, MA 02170. Second class postage is paid at Boston, MA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Subscription to BIRD OBSERVER is based on a calendar year, from January to December, at $8.50 per year. Back issues are available at $7.50 per year or $1.50 per issue. -

Annual Report Table of Contents

University of Massachusetts Lowell Fiscal Year 2015 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS CAMPUS RECREATION AT A GLANCE 2 Our Mission 2 Organizational Chart 3 Year In Review 4 PROGRAMS 5 Intramural Sports 5 Club Sports 7 Group Fitness 9 Personal Training 11 Wellness Programs 13 Outdoor Adventure 15 Bike Shop & Bike Share 17 Youth Programs 19 Community Programs 21 Kayak Center and Boathouse 23 UMass Lowell Campus Recreation is committed to excellence in supporting the development of STUDENT EMPLOYMENT 25 healthier and happier lifestyles. Through experiential education we strive to teach students the importance of exercise and recreational activities in preparation for a productive, balanced and Student Payroll and Staff Demographics 25 rewarding life. We will offer diverse and dynamic recreational programming and facilities in order OPERATIONS 27 to meet the needs of our students and create a fun and connected University Community. Facilities 27 Memberships 29 Risk Management 30 MARKETING & PROMOTIONS 31 Social Media 31 CAMPUS RECREATION ORGANIZATIONAL CHART FY ‘15 YEAR IN REVIEW Campus Recreation had a very successful 2014 – 2015 academic year. For the purposes of this report, Campus Recreation focused on participation as our main indicator of success. A large part of this year’s success can be attributed to the addition of staff and financial support. We have used these resources to better serve and support our students and this is demonstrated through the growth in both participation and programs offered. While we have seen achievement throughout all areas, the following bullets are some of our most notable highlights from this past year. Intramural Sports has seen a dramatic increase in participation over the past three years rising from 3,500 participants to nearly 6,000 this year.