Oral History Interview with Shepard Fairey, 2011 Feb. 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ART & POLITICS Graphic Art in the Summer of Discontent

ART & POLITICS Graphic Art in the Summer of Discontent The 2004 election has attracted artists in numbers not seen for a generation. Their designs give progressive politics a distinct visibility. BY FAYE HIRSCH ew York, late June 2004: On a wall of feel-good tape outlines shaped like shirts. In a cel iPod ads showing wired-up kids in silhouette ebratory atmosphere, visitors selected Ndancing against electric-colored backgrounds, their favorites to be printed on the spot there appears, for a few hours, the now-iconic hood as T-shirts (the proceeds, at $30 a pop, ed prisoner who has become the emblem of the Abu went to the Democratic National Ghraib scandal. Like the ad kids, this figure, too, is Committee). Like "Power T's," many rendered in black silhouette on Day-G io; but the exhibitions were up for just a week or wiring connects to a far different tale. Were it not for two, coinciding with the convention. the Internet, medium of choice for latter-day agitprop, Among veteran artists with new work this "iRaq" intervention might seem like urban legend: was Sue Coe, showing drawings at by the time one returns for a reality check, to Broome Galerie St. Etienne for her book, just Street, to Bond and Lafayette, to last night's subway issued, Bully: Master of the Global platform, the poster has vanished. Yet, on the Web, a Merry-Go-Round, which she co-authored record of the action is disseminated, a salvo in the with writer Judith Brody (Four Walls Eight multi-front war against political-and visual-compla Windows, $18). -

Southern California Artists Challenge America Paul Von Blum After the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001, America Experienc

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 20 (2004) : 17-27 Southern California Artists Challenge America Paul Von Blum After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, America experienced an outpouring of international sympathy. Political leaders and millions of people throughout the world expressed heartfelt grief for the great loss of life in the wake of the unspeakable horror at the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and in Pennsylvania. Four years later, America has had its world standing and moral credibility substantially reduced. In striking contrast to the immediate aftermath of 9/11, it faces profound isolation and disrespect throughout the world. The increasingly protracted war in Iraq has been the major catalyst for massive international disapproval. Moreover, the arrogance of the George W. Bush administration in world affairs has alienated many of America’s traditional allies and has precipitated widespread global demonstrations against its policies and priorities. Domestically, the Bush presidency has galvanized enormous opposition and has divided the nation more deeply than any time since the height of the equally unpopular war in Vietnam. Dissent against President Bush and his retrograde socio-economic agenda has become a powerful force in contemporary American life. Among the most prominent of those commenting upon American policies have been members of the artistic community. Musicians, writers, filmmakers, actors, dancers, visual artists, and other artists continue a long-held practice of using their creative talents to call dramatic attention to the enormous gap between American ideals of freedom, justice, equality, and peace and American realities of racism, sexism, and international aggression. In 2004, for example, Michael Moore’s film “Fahrenheit 9/11,” which is highly critical of President Bush, has attracted large audiences in the United States and abroad. -

How the Commercialization of American Street Art Marks the End of a Subcultural Movement

SAMO© IS REALLY DEAD1: How the Commercialization of American Street Art Marks the End of a Subcultural Movement Sharing a canvas with an entire city of vandals, a young man dressed in a knit cap and windbreaker balances atop a subway handrail, claiming the small blank space on the ceiling for himself. Arms outstretched, he scrawls his name in loops of black spray paint, leaving behind his distinct tag that reads, “FlipOne.”2 Taking hold in the mid ‘70s, graffiti in New York City ran rampant; young artists like FlipOne tagged every inch of the city’s subway system, turning the cars into scratchpads and the platforms into galleries.3 In broad daylight, aerosolcanyeilding graffiti artists thoroughly painted the Lower East Side, igniting what would become a massive American subculture movement known as street art. Led by the nation’s most economically depressed communities, the movement flourished in the early ‘80s, becoming an outlet of expression for the underprivileged youth of America. Under state law, uncommissioned street art in the United States is an act of vandalism and thereby, a criminal offense.4 As a result of the form’s illegal status, it became an artistic manifestation of rebellion, granting street art an even greater power on account of its uncensored, defiant nature. Demonized for its association with gang violence, poverty, and crime, local governments began cracking down on inner city street art, ultimately waging war upon the movement itself. As American cities worked to reclaim their streets and rid them of graffiti, the movement eventually came to a standstill, giving way to cleaner, more prosperous inner city communities. -

Bennett Bean Playing by His Rules by Karen S

March 1998 1 2 CERAMICS MONTHLY March 1998 Volume 46 Number 3 Wheel-thrown stoneware forms by Toshiko Takaezu at the American Craft FEATURES Inlaid-slip-decorated Museum in vessel by Eileen New York City. 37 Form and Energy Goldenberg. 37 The Work of Toshiko Takaezu by Tony Dubis Merino 75 39 George Wright Oregon Potters’ Friend and Inventor Extraordinaire by Janet Buskirk 43 Bennett Bean Playing by His Rules by Karen S. Chambers with Making a Bean Pot 47 The Perfect Clay Body? by JejfZamek A guide to formulating clay bodies 49 A Conversation with Phil and Terri Mayhew by Ann Wells Cone 16 functional porcelain Intellectually driven work by William Parry. 54 Collecting Maniaby Thomas G. Turnquist A personal look at the joy pots can bring 63 57 Ordering Chaos by Dannon Rhudy Innovative handbuilding with textured slabs with The Process "Hair of the Dog" clay 63 William Parry maker George Wright. The Medium Is Insistent by Richard Zakin 39 67 David Atamanchuk by Joel Perron Work by a Canadian artist grounded in Japanese style 70 Clayarters International by CarolJ. Ratliff Online discussion group shows marketing sawy 75 Inspirations by Eileen P. Goldenberg Basket built from textured Diverse sources spark creativity slabs by Dannon Rhudy. The cover: New Jersey 108 Suggestive Symbols by David Benge 57 artist Bennett Bean; see Eclectic images on slip-cast, press-molded sculpture page 43. March 1998 3 UP FRONT 12 The Senator Throws a Party by Nan Krutchkoff Dinnerware commissioned from Seattle ceramist Carol Gouthro 12 Billy Ray Hussey EditorRuth -

Art Review the Art of Shepard Fairey: Questioning Everything

Vol. 10, No. 2 International Journal of Multicultural Education 2008 Art Review The Art of Shepard Fairey: Questioning Everything Hwa Young Caruso, Ed. D. Art Review Editor Selected Artworks of Shepard Fairey Exhibitions Acknowledgment Reference Given the recent erosion of the United States’ moral reputation and economic status as a super power, the social and political criticism of Shepard Fairey’s street art becomes more poignant. Fairey is a street artist who speaks out against the abuse of power and militarism while supporting people of color and women who seek equity. Abandoned buildings, empty wall spaces, and streets have become his blank canvas and target to raise his voice and pose questions. During the summer of 2007, the Jonathan Levine Gallery introduced Shepard Fairey in his first New York City solo exhibition. Thousands of viewers saw his works at the gallery in Chelsea and the D.U.M.B.O. Installation Space in Brooklyn, New York. The title of the exhibition, “E Pluribus Venom” (out of many, poison), parodied the Great Seal of “E Pluribus Unum” (out of many, one) which appears on US currency. Public interest in Fairey’s works and the magnetic power of his persuasive visual rhetoric created great interest in the younger generation of art enthusiasts, critical reviewers, and collectors. Fairey’s first New York City solo exhibition was sold out. Shepard Fairey was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1970. He studied illustration art at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1991 and is currently living and working in Los Angeles. He began his street art project in Rhode Island and spent time in the neighborhood on his skateboard. -

Shepard Fairey V1 USD.Pdf

V1 GALLERY PROUDLY PRESENTS YOUR AD HERE – A SOLO EXHIBITION BY SHEPARD FAIREY OPENING: FRIDAY AUGUST 5. 2011. TIME: 17.00 - 22.00 EXHIBITION PERIOD: AUGUST 6. – SEPTEMBER 3. 2011 It is a great pleasure to welcome Shepard Fairey back to Copenhagen for his second solo exhibition at V1 Gallery. Since Fairey’s first exhibition at the Gallery in 2004, he has aided the change of American history with his iconic Hope poster for Barack Obama’s presidential campaign, contributed to the countinous debate about art in public space with numerous exhibitions in public and private arenas. Most recently with his participation in the Oscar nominated Banksy documentary “Exit Through The Gift Shop” and the current “Art In The Streets” exhibition at MOCA in Los Angeles. “Your Ad Here”, recent works by Shepard Fairey, comprises a broad array of mixed media works on canvas and paper, as well as screen prints, retired stencils, and Rubylith cuts. Building upon Fairey’s history of questioning the control of public space and public discourse, much of the art in “Your Ad Here” examines advertising and salesmanship as tools of propaganda and influence. One series in “Your Ad Here” portrays politicians like Reagan and Nixon as insincere salesmen wielding simple slogans that represent their true agendas when stripped of verbose demagoguery. Another series of works are paintings of Fairey’s “Obey” icon face in various urban settings usually reserved for advertising as the primary visual. These works showcase the power of images in the public space, and encourage the viewer to think of public space as more than a one-way dialogue with advertising, but as a venue for creative response. -

For the Love of Spraying – Graffiti, Urban Art and Street Art in Munich

Page 1 For the love of spraying – Graffiti, urban art and street art in Munich (21 January 2018) Believe it or not, Munich was a pioneer of the German graffiti scene. As the graffiti wave arrived from New York and swept through Europe during the early ‘80s, it was Munich that rode that wave even before Berlin. Some of today’s leading figures in the international graffiti scene were immortalised by their legally-painted murals in what was, at the time, the largest Hall of Fame in Europe on the flea market grounds on Dachauer Straße – though the thrill of illegal spraying was also of course a driving force behind the Munich scene. By the late 1990s, Munich was considered a mecca for graffiti artists, alongside New York. Today, there are several sites in Munich displaying a wide variety of urban art, and they have long been considered a boon to the city. Over the years, legends of the street art scene such as BLU, ESCIF, Shepard Fairey and Mark Jenkins have discovered Munich for themselves and, in collaboration with the Positive Propaganda e.V. art association, have used art to breathe new life into public spaces in the city. The first German museum of urban art, MUCA (Museum of Urban and Contemporary Art), doesn't just showcase celebrated artists, but also offers a stage for experimental formats. A whole range of forums, events and guided tours bring these contemporary, quirky, energy-charged art forms to life in Munich. Contact: Department of Labor and Economic Development München Tourismus, Trade & Media Relations Herzog-Wilhelm-Str. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Page 1/3 Urban Nation Brings US Street Art Icon to Berlin: Shepard Fairey Creates Spectacular Work of Art in Kreuzberg “Make art not war” – Shepard Fairey’s artwork is pregnant with meaning. © Henrik Haven Berlin, 22 September 2014 Ateliers, legendary cinemas, alternative bars – Kreuzberg is cool. Now, Berlin’s hip district has a new, extraordinary artwork: a gigantic red rose, its stem locked in a shackle, beneath the slogan “MAKE ART NOT WAR”. The large-scale mural was sprayed by no less than the US street art icon Shepard Fairey. The painting is located right at the entrance to the U-Bahn station Hallesches Tor, Mehringplatz, at the beginning of Friedrichstraße. Nobody can pass it by without admiring it. Shepard Fairey consciously chose this district: “I was in Berlin for a few days in 2003. I have hardly ever seen so much graffiti in one place as in Kreuzberg. There is so much youth culture and energy to soak up – it was great working here and it certainly won’t be the last time.” Fairey said he did not just sense a great interest in street art in Kreuzberg, but also a lot of positive energy to create new art. – – – Press contacts Inquiries regarding the artists: General media inquiries: Yasha Young Volker Hartig Fon: 0172 3125500 Fon: 030 4708-1521 [email protected] [email protected] Page 2/3 Understanding the City, Shaping the City – Art for Berlin The art event was initiated by the network Urban Nation, which sees itself as a platform for artists, projects and community. -

Rebranding Street Art: an Examination of Street Art and Evolution Into Mainstream Advertising, Branding, and Propaganda

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 5-25-2018 Rebranding Street Art: An Examination of Street Art and Evolution into Mainstream Advertising, Branding, and Propaganda Moira Fiona Hampson Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hampson, Moira Fiona, "Rebranding Street Art: An Examination of Street Art and Evolution into Mainstream Advertising, Branding, and Propaganda" (2018). University Honors Theses. Paper 631. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.642 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Rebranding Street Art An examination of street art and evolution into mainstream advertising, branding, and propaganda. by Moira Fiona Hampson An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts In University Honors and Communication Studies Thesis Adviser Dr. Cynthia Lou Coleman Portland State University 2018 REBRANDING STREET ART Abstract An examination of the evolution of street art arising from an elemental form of graffiti/vandalism to an established and respected art form used by corporate organizations for advertisement and branding. This case study will provide testimony of research performed over the span of twenty years allowing for the development of acclaimed street artists like Shepard Fairey to establish their own brand identities and collaborations with corporate advertising. This will be exhibited by breaking down what street art is and how it relates to advertising, branding, and propaganda. -

Alexandra Grant

LOWELL RYAN PROJECTS Alexandra Grant Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA Education 2000 MFA, Drawing and Painting, California College of Arts and Crafts, San Francisco, CA. 1995 BA, History and Studio Art, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA. Solo Exhibitions 2020 Solo Booth, Marfa Invitational, Marfa, TX. 2019 Born to Love, Lowell Ryan Projects, Los Angeles, CA. 2017 Shadows, Galerie Gradiva, Paris, France. ghost town, Galería Marco Augusto Quiroa en Casa Santo Domingo, Antigua, Guatemala. Antigone is you is me, Eastern Star Gallery, Archer School for Girls, Los Angeles, CA. 2016 Shadows, Ochi Gallery, Sun Valley, ID. ghost town, 20th Bienal de Arte Paiz, Guatemala City, Guatemala. 2015 A Perpetual Slow Circle, Ochi Gallery, Sun Valley, ID. 2014 Century of the Self, Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin, TX. 2013 Forêt Intérieure/Interior Forest, Mains d’Oeuvres, Saint Ouen, France. Forêt Intérieure/Interior Forest, 18th Street Arts Center, Santa Monica, CA. 2011 The Womb-Womb Room, Night Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Collaboration with Channing Hansen. 2010 Bodies, Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. 2008 A.D.D.G. (aux dehors de guillemets), Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. 2007 MOCA Focus Show, Curated by Alma Ruiz, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA. 2004 Homecoming, Gallery Sixteen:One, Santa Monica, CA. Selected Group Exhibitions 2019 Oneric Landscapes, Five Car Garage, Los Angeles, CA. 2018 Freewaves: Dis…Miss, curated by Anne Bray, Sam Francis Gallery, Crossroads School, Santa Monica, CA. BENT, Merchant Gallery, Santa Monica, CA. The mecca, California, Eastern Star Gallery in partnership with The Lodge, Los Angeles, CA. 4851 West Adams Blvd. -

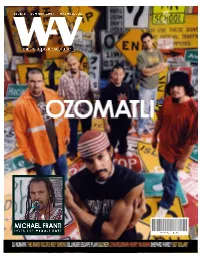

WAV / Kotori Magazine Issue 2 Ozomatli Michael Franti DJ Numark the Mars Volta's Ikey Owens Dillinger

Serrated Intellect jason mascow We’re coming closer and closer to one of the most important days of the rest of our lives. i know you’re probably sick and tired of hearing it by now, but it’s something we’ve just got to suck up. I mean, letz face it, there’s a hell of a reason to. November 2, 2004. Election day. I hate to introduce WAV magazine’s long-awaited second issue with a topic sure to elicit more jeer than cheer, but I trust you can respect itz immediacy. Immediacy that has prompted the artists and personalities we love, hate, and admire, to dedicate a good chunk of their obligation to. Of the countless events we attended over the past few years, there has existed at least a brief moment, often times full-on ‘speeches,’ dedicated to speaking up against the direction our beautiful, once- not-too-long-ago respected country is headed. And they do it out of pure passion and heartfelt belief, many times angering the businesses, marketers, government, corporations, sponsors…basically the money… behind them. and wasn’t that the idea in the first place? scare us into thinking that the only right way was their way? But still, the artists feel they just have to. After seeing a steady stream of this at just about every club I walked into, every festival lawn I frolicked on, every stage, theater, and coffeehouse I visited, I realized that i was not alone…and with this empowerment, I started to become less and less afraid. -

California State University, Northridge Shepard Fairey

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE SHEPARD FAIREY AND STREET ART AS POLITICAL PROPAGANDA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Art, Art History by Andrea Newell August 2016 Copyright by Andrea Newell 2016 ii The thesis of Andrea Newell is approved: _______________________________________________ ____________ Meiqin Wang, Ph.D. Date _______________________________________________ ____________ Owen Doonan, Ph.D. Date _______________________________________________ ____________ Mario Ontiveros, Ph.D., Chair Date California State University, Northridge iii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Mario Ontiveros of the Art Department at California State University, Northridge. He always challenged me in a way that brought out my best work. Our countless conversations pushed me to develop a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of my research and writing as well as my knowledge of theory, art practices and the complexities of the art world. He consistently allowed this paper to be my own work, but guided me whenever he thought I needed it, my sincerest thanks. My deepest gratitude also goes out to my committee, Dr. Meiqin Wang and Dr. Owen Doonan, whose thoughtful comments, kind words, and assurances helped this research project come to fruition. Without their passionate participation and input, this thesis could not have been successfully completed. I would also like to acknowledge Dr. Peri Klemm for her constant support beyond this thesis and her eagerness to provide growth opportunities in my career as an art historian and educator. I am gratefully indebted to my co-worker Jessica O’Dowd for our numerous conversations and her input as both a friend and colleague.