Examination of Firearms and Forensics in Europe and Across Territories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004: Volume 16

2 Journal on Firearms and Public Policy VOLUME 16 The Journal on Firearms and Public Policy is the official publication of the Center for the Study of Firearms and Public Policy of the Second Amendment Foundation. Editor Publisher David B. Kopel, J.D. Julianne Versnel Gottlieb Independence Institute Women & Guns Magazine Board of Advisors Randy E. Barnett, J.D. Edward F. Leddy, Ph.D. David Bordua, Ph.D. Andrew McClurg, J.D. David I. Caplan, Ph.D., J.D. Glenn Harlan Reynolds, J.D. Brendan Furnish, Ph.D. Joseph P. Tartaro Alan M. Gottlieb William Tonso, Ph.D. Don B. Kates, Jr., J.D. Eugene Volokh, J.D. Gary Kleck, Ph.D. James K. Whisker, Ph.D. Journal Policy The Second Amendment Foundation sponsors this journal to encourage objective research. The Foundation invites submission of research papers of scholarly quality from a variety of disciplines, regardless of whether their conclusions support the Foundation's positions on controversial issues. Manuscripts should be sent in duplicate to: Center for the Study on Firearms and Public Policy, a division of the Second Amendment Foundation, 12500 N.E. Tenth Place, Bellevue, Washington 98005 or sent via email to www.saf.org 3 This publication is copyrighted ©2004 by the Second Amendment Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. The Second Amendment Foundation is a non-profit educational foundation dedicated to promoting a better understanding of our Constitutional heritage to privately own and possess firearms. -

NL-ARMS O;Cer Education

NL-ARMS Netherlands Annual Review of Military Studies 2003 O;cer Education The Road to Athens! Harry Kirkels Wim Klinkert René Moelker (eds.) The cover image of this edition of NL-ARMS is a photograph of a fragment of the uni- que ‘eye tiles’, discovered during a restoration of the Castle of Breda, the home of the RNLMA. They are thought to have constituted the entire floor space of the Grand North Gallery in the Palace of Henry III (1483-1538). They are attributed to the famous Antwerp artist Guido de Savino (?-1541). The eyes are believed to symbolize vigilance and just government. NL-Arms is published under the auspices of the Dean of the Royal Netherlands Military Academy (RNLMA (KMA)). For more information about NL-ARMS and/or additional copies contact the editors, or the Academy Research Centre of the RNLMA (KMA), at adress below: Royal Netherlands Military Academy (KMA) - Academy Research Centre P.O. Box 90.002 4800 PA Breda Phone: +31 76 527 3319 Fax: +31 76 527 3322 NL-ARMS 1997 The Bosnian Experience J.L.M. Soeters, J.H. Rovers [eds.] 1998 The Commander’s Responsibility in Difficult Circumstances A.L.W. Vogelaar, K.F. Muusse, J.H. Rovers [eds.] 1999 Information Operations J.M.J. Bosch, H.A.M. Luiijf, A.R. Mollema [eds.] 2000 Information in Context H.P.M. Jägers, H.F.M. Kirkels, M.V. Metselaar, G.C.A. Steenbakkers [eds.] 2001 Issued together with Volume 2000 2002 Civil-Military Cooperation: A Marriage of Reason M.T.I. Bollen, R.V. -

Civil-Military Capacities for European Security

Clingendael Report Civil-Military Capacities for European Security Margriet Drent Kees Homan Dick Zandee Civil-Military Capacities for European Security Civil-Military Capacities for European Security Margriet Drent Kees Homan Dick Zandee © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders. Image rights: Drone, Binary Code: © Shutterstock.com Search and Rescue squadron: © David Fowler / Shutterstock.com Design: Textcetera, The Hague Print: Gildeprint, Enschede Clingendael Institute P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague The Netherlands Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl/ Content Executive summary 7 Introduction 11 1 The external-internal security gap 13 2 Case study maritime security 25 3 Case study border security 39 4 Case study cyber security 53 5 Conclusions and recommendations 64 List of acronyms 70 5 Executive summary In the last two decades the European Union has created separated policies, institutions and capacities for external and internal security. In the meantime the world’s security environment has changed fundamentally. Today, it is no longer possible to make a clear distinction between security outside and within Europe. Conflicts elsewhere in the world often have direct spill-over effects, not primarily in terms of military threats but by challenges posed by illegal immigration, terrorism, international crime and illegal trade. Lampedusa has become a synonym for tragedy. Crises and instability in Africa, the Middle East and elsewhere in the world provide breeding grounds for extremism, weapons smuggling, drugs trafficking or kidnapping. -

The Future of Police Missions

The Future of Police Missions Franca van der Laan Luc van de Goor Rob Hendriks Jaïr van der Lijn Clingendael Report Minke Meijnders Dick Zandee The Future of Police Missions Franca van der Laan Luc van de Goor Rob Hendriks Jaïr van der Lijn Minke Meijnders Dick Zandee Clingendael Report February 2016 February 2016 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: KMar (Koninklijke Marechaussee) Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user reproduce, distribute or display material from Clingendael publications or any other source for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material on or any copies of the material. Material may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Franca van der Laan is a Senior Research Fellow, seconded by the Dutch Police at Clingendael. She focuses on international police cooperation issues, transnational organised crime and terrorism. Luc van de Goor is Director Research at the Clingendael Institute. -

Netherlands from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia This Article Is About the Constituent Country Within the Kingdom of the Netherlands

Netherlands From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the constituent country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. For other uses, see Netherlands (disambiguation). Not to be confused with Holland (disambiguation). Netherlands Nederland (Dutch) Flag Coat of arms Motto: "Je maintiendrai" (French) "Ik zal handhaven" (Dutch) "I will uphold"[a] Anthem: "Wilhelmus" (Dutch) "'William" MENU 0:00 Location of the European Netherlands (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) – in the European Union (green) Location of the Dutch special municipalities (green) Capital Amsterdam[b] and largest city 52°22′N 4°53′E Official languages Dutch Recognised West Frisian,Limburgish, Dutch Low regional languages Saxon, English,Papiamento[c] Ethnic groups(2014[1]) 78.6% Dutch 5.9% other EU 2.4% Turks 2.2% Indonesians 2.2% Moroccans 2.1% Surinamese 0.9% Caribbean 5.7% others Demonym Dutch Sovereign state Kingdom of the Netherlands Government Unitary parliamentaryconstitutional monarchy - Monarch Willem-Alexander - Prime Minister Mark Rutte Legislature States General - Upper house Senate - Lower house House of Representatives Area - Total 41,543 km2 (134th) 16,039 sq mi - Water (%) 18.41 Population - 2014 estimate 16,912,640[2] (63rd) - Density 406.7/km2 (24th) 1,053.4/sq mi GDP (PPP) 2014 estimate - Total $798.106 billion[3] (27th) - Per capita $47,365 (13th) GDP (nominal) 2014 estimate - Total $880.394 billion[3] (16th) - Per capita $52,249 (10th) Gini (2011) 25.8[4] low · 111th HDI (2013) 0.915[5] very high · 4th Euro (EUR) Currency US dollar (USD)[d] Time zone CET (UTC+1)[e] AST (UTC-4) - Summer (DST) CEST (UTC+2) AST (UTC-4) Date format dd-mm-yyyy Drives on the right +31 Calling code +599[f] ISO 3166 code NL [g] Internet TLD .nl The Netherlands is the main constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. -

Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

University of Bath PHD Working with disaster: Transforming experience into useful practice: How I used action research to guide my path while walking it Capewell, Elizabeth Ann Award date: 2004 Awarding institution: University of Bath Link to publication Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 1 WORKING WITH DISASTER: TRANSFORMING EXPERIENCE INTO A USEFUL PRACTICE How I used action research to guide my path while walking it ELIZABETH ANN CAPEWELL A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bath Centre for Action Research in Professional Practice School of Management December 2004 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that -

Bds the First Forty Years 1963-2003

BDS THE FIRST FORTY YEARS 1963-2003 Four decades of work for the welfare of deer A Personal View and Memoir by Founder Member Peter Carne CHAPTERS 1. Why a British Deer Society? 2. The Deer Group 3. Birth of the BDS 4. Early days 5. Forging ahead 6. Onward and upward 7. Further Branch development 8. The Journal 9. Moving on 10. Spreading the load 11. Into the ‘70s 12. Celebrating a birthday 13. After the party 14. Growing pains 15. Going professional 16. Royal Patronage 17. Business as usual 18. So far so good 19. Into the 1980’s 20. Twenty years on 21. Ufton Nervet 22. Child-Beale 23. Happier times 24. The early 1990s 25. Our Fourth decade 26. Thirty years on 27. A new era 28. Changing times 29. A Company limited by Guarantee 30. 2000 not out! 31. All change! 32. Anniversary count down 33. Epilogue Appendix: Illustrations The British Deer Society accepts no responsibility for interpretations of fact or expressions of opinion in the accompanying text, which are entirely those of the author. Peter Carne has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as Author of this work. 2 1. Why a British Deer Society? THE FIRST HALF of the twentieth century was a dark age for British deer, in England especially. Two world wars and their aftermath saw the closure of very many ancient deer parks. Some were converted to farmland for wartime and post war food production. Others were requisitioned as sites for military camps or for other defence purposes. -

The OSCE Secretariat Bears No Responsibility for the Content of This Document FSC.EMI/313/20 and Circulates It Without Altering Its Content

The OSCE Secretariat bears no responsibility for the content of this document FSC.EMI/313/20 and circulates it without altering its content. The distribution by OSCE 8 July 2020 Conference Services of this document is without prejudice to OSCE decisions, as set out in documents agreed by OSCE participating States. ENGLISH only QUESTIONNAIRE ON THE CODE OF CONDUCT ON POLITICO-MILITARY ASPECTS OF SECURITY 2019 THE NETHERLANDS Section I: Inter-State elements 1. Account of measures to prevent and combat terrorism 1.1 To which agreements and arrangements (universal, regional, sub-regional and bilateral) related to preventing and combating terrorism is your State a party? See Annex 1.2 What national legislation has been adopted in your State to implement the above-mentioned agreements and arrangements? The Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations and the Ministry of Justice and Security report on progress made to Parliament on a regular basis. 1.3 What are the roles and missions of military, paramilitary and security forces and the police in preventing and combating terrorism in your State? The National Coordinator for Counterterrorism and Security (NCTV) plays a central role in preventing and combating terrorism. NCTV coordinates the efforts of the responsible ministries (mainly Interior and Kingdom Relations and Justice & Security). Within the Netherlands, the Ministry of Defence and the Armed Forces have a supporting role in this area. Combating terrorism is one of the main tasks of the Central Unit of the Netherlands Police. It includes many divisions and teams who play an important role in fighting terrorism and radicalization. -

Police Use of Force – a Contextual Study of 'Suicide by Cop'

Police Use of Force – A contextual study of ‘Suicide by Cop’ within the British Policing Paradigm. by Nicholas FRANCIS Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the degree of MSc by Research. 2019. CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINALITY. This thesis is a presentation of my original research work. This is to certify that I am responsible for the work submitted in this thesis, that the original work is my own except as specified in acknowledgments or in footnotes. Wherever contributions of others are involved, every effort is made to indicate this clearly, with due reference and acknowledgement to the literature. Neither this thesis nor the original work contained therein has been submitted to this or any other institution for a degree. ……………………………………………. Nicholas FRANCIS Word Count = 32,976 Nicholas FRANCIS ii Acknowledgements I would like to make the following acknowledgements: Firstly, to my supervisor Professor Robin Bryant. He has guided me thorough this process with extreme patience, kind and critical feedback with insights I have found exceptionally valuable. I don’t know whether to thank him for this or not as it has given me some real head scratching moments; but for also opening up the world of statistical analysis, which I was not expecting and still have a lot to learn. To Professor Stephen Tong, thank you for your sage advice in my supervision meetings and since. Your feedback throughout has been really encouraging and supportive. To Dr Emma Williams, as always your energetic spirit is infectious and kind supportive encouragement most welcome. To Jenny Norman whose guidance and support, especially relating to qualitative research, survey methods and design, with your feedback on my draft was essential. -

The Branch January 2020

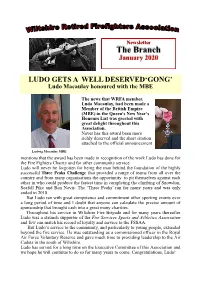

Newsletter The Branch January 2020 LUDO GETS A WELL DESERVED‘GONG’ Ludo Macaulay honoured with the MBE The news that WRFA member, Ludo Macaulay, had been made a Member of the British Empire (MBE) in the Queen's New Year’s Honours List was greeted with great delight throughout this Association. Never has this award been more richly deserved and the short citation attached to the official announcement Ludwig Macaulay MBE mentions that the award has been made in recognition of the work Ludo has done for the Fire Fighters Charity and for other community service. Ludo will never be forgotten for being the man behind the foundation of the highly successful Three Peaks Challenge that provided a range of teams from all over the country and from many organisations the opportunity to pit themselves against each other in who could produce the fastest time in completing the climbing of Snowdon, Scafell Pike and Ben Nevis. The ‘Three Peaks’ ran for many years and was only ended in 2018. But Ludo ran with great competence and commitment other sporting events over a long period of time and I doubt that anyone can calculate the precise amount of sponsorship that brought cash into a great many charities. Throughout his service in Wiltshire Fire Brigade and for many years thereafter Ludo was a staunch supporter of the Fire Services Sports and Athletics Association and few can match his record of loyalty and service to the FSSAA. But Ludo’s service to the community, and particularly to young people, extended beyond the fire service. -

Clingendael's Vision for the Future of the Armed Forces of the Netherlands

Clingendael’s Vision for the Future of the Armed Forces of the Netherlands Ko Colijn Margriet Drent Kees Homan Jan Rood Dick Zandee Clingendael Report Clingendael’s Vision for the Future of the Armed Forces of the Netherlands Ko Colijn Margriet Drent Kees Homan Jan Rood Dick Zandee 1 Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague Phone number: +31 (0)70 3245384 Telefax: +31 (0)70 3282002 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl July 2013 (printed in Dutch February 2013) © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, either electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Clingendael Institute.. Contents Executive summary 4 Introduction 7 1 Interests and values in the foreign policy of the Netherlands 11 2 Options for the armed forces of the Netherlands 16 The air-based intervention force 18 The maritime force 20 The robust stabilisation force 22 The supporting peace force 24 Implications for the main tasks 26 3 Conclusions 27 3 Executive summary The defence budget cuts combined with rising costs for replacing the F-16 require a ‘vision for the future of the armed forces of the Netherlands’, which the Rutte-II government will deliver in 2013. Difficult decisions lie ahead with regard to the structure of the armed forces of the Netherlands as reduced financial resources no longer suffice to cover the costs of maintaining all existing capabilities and modernising them when required. -

Download the Publication

Foreword By Dr. Karen Finkenbinder Michael Burgoyne has made a valuable contribution to stabilization. The 21st century requires a new way of thinking. U.S. experts such as David Bayley, Robert Perito, and Michael Dziedzic have discussed a security gap in post-conflict and failed states, and promoted ways to close it. The U.S. model of decentralized policing is not it. Rather, as Burgoyne notes, we must look to our partners that have Gendarmerie Type Forces (GTF) – Stability Police Forces. Though others may be able to do stability policing in the short-term, Stability Police made up of GTF are the best approach. They have extensive expertise and experience policing civilian communities (the latter lacking in military forces), often in high-crime and insecure environments. As Burgoyne rightly observes, “the military lacks expertise in policing and law enforcement which can create a counterproductive outcome when training foreign police forces. Even military police lack the community policing knowledge resident in European SPFs.” Rather than enable minimally qualified U.S. contractors or use military personnel, the United States should continue to partner with the Center of Excellence for Stability Policing Units (CoESPU) in Vicenza, Italy, an organization that includes GTF officers from many countries and develops international stability police. Similarly, the United States should support the development of the NATO Stability Police Concept that envisions military forces quickly transitioning to stability police who either replace or reinforce indigenous forces. And, the United States should support efforts by the European Gendarmerie Forces (EUROGENDFOR) to enable their deployment in support of European partners.