Sensibility and Science !" !# Jed Perl Jed Perl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

He Museum of Modern Art No

n^ he Museum of Modern Art No. 15 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart FOR REIi^ASE: West Wednesday, February I, I967 PRESS PREVIEW: Tuesday, January 31, I967 11 a .IB. - U p.m. CALDER: I9 GIFTS FROM THE ARTIST, an exhibition of mobiles, stabiles, wood and wire sculptures and jewelry recently given to The Museum of Modern Art by the famous American artist, Alexander Calder, will be on view at the Museum from February 1 through April 5. The works in the exhibition range from Gaidar's early wire por traits of the I92O6, through various other periods and media, to a montanental mobile- stabile made in I96U. The 19 works by Calder, added to those already owned by the Museum, make this the largest and most complete collection by the artist in any museum. Thi# very geoerous gift caoe about in M^y I966 when Calder invited the Museum to make a choice from the contents of his Connecticut studio in recognition of the Museum's having given hin in 19i)3 bis first large retrospective exhibition« The major piece among Gaidar's recent gifts is Sandy's Butterfly, I96U, a great mobile-stabile of stainless steel painted red, white, black and yellow and standing nearly I3 feet high. Too tall to be shown indoors with the rest of the exhibition, this piece stands on the terrace just outside the Museum's Main Hall; it will later be moved to the upper terrace of the Sculpture Garden. Another work of the 1960s in the exhibition is a 2l^inch Model for "Teodelapio", the great steel stabile made in I962 for the Festival of Two Worlds at Spoleto, Italy. -

19 Gifts from the Artist

n^ he Museum of Modern Art No. 15 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart FOR REIi^ASE: West Wednesday, February I, I967 PRESS PREVIEW: Tuesday, January 31, I967 11 a .IB. - U p.m. CALDER: I9 GIFTS FROM THE ARTIST, an exhibition of mobiles, stabiles, wood and wire sculptures and jewelry recently given to The Museum of Modern Art by the famous American artist, Alexander Calder, will be on view at the Museum from February 1 through April 5. The works in the exhibition range from Gaidar's early wire por traits of the I92O6, through various other periods and media, to a montanental mobile- stabile made in I96U. The 19 works by Calder, added to those already owned by the Museum, make this the largest and most complete collection by the artist in any museum. Thi# very geoerous gift caoe about in M^y I966 when Calder invited the Museum to make a choice from the contents of his Connecticut studio in recognition of the Museum's having given hin in 19i)3 bis first large retrospective exhibition« The major piece among Gaidar's recent gifts is Sandy's Butterfly, I96U, a great mobile-stabile of stainless steel painted red, white, black and yellow and standing nearly I3 feet high. Too tall to be shown indoors with the rest of the exhibition, this piece stands on the terrace just outside the Museum's Main Hall; it will later be moved to the upper terrace of the Sculpture Garden. Another work of the 1960s in the exhibition is a 2l^inch Model for "Teodelapio", the great steel stabile made in I962 for the Festival of Two Worlds at Spoleto, Italy. -

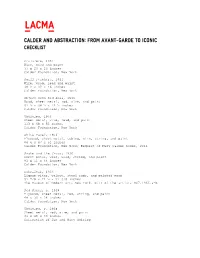

Calder and Abstraction: from AVANT-GARDE to Iconic CHECKLIST

^ Calder and Abstraction: from AVANT-GARDE TO IconIC CHECKLIST Croisiére , 1931 Wire, wood and paint 37 x 23 x 23 inches Calder Foundation, New York Small Feathers , 1931 Wire, wood, lead and paint 38 ½ x 32 x 16 inches Calder Foundation, New York Object with Red Ball , 1931 Wood, sheet metal, rod, wire, and paint 61 ¼ x 38 ½ x 12 ¼ inches Calder Foundation, New York Untitled , 1934 Sheet metal, wire, lead, and paint 113 x 68 x 53 inches Calder Foundation, New York White Panel , 1936 Plywood, sheet metal, tubing, wire, string, and paint 84 ½ x 47 x 51 inches Calder Foundation, New York; Bequest of Mary Calder Rower, 2011 Snake and the Cross , 1936 Sheet metal, wire, wood, string, and paint 81 x 51 x 44 inches Calder Foundation, New York Gibraltar , 1936 Lignum vitae, walnut, steel rods, and painted wood 51 7/8 x 24 ¼ x 11 3/8 inches The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist, 847.1966.a-b Red Panel , c. 1938 Plywood, sheet metal, rod, string, and paint 48 x 30 x 24 inches Calder Foundation, New York Untitled , c. 1938 Sheet metal, rod, wire, and paint 31 x 48 x 39 inches Collection of Jon and Mary Shirley La Demoiselle , 1939 Sheet metal, wire, and paint 58 ½ x 21 x 29 ½ inches Glenstone Untitled , 1939 Sheet metal, rod, wire, and paint55 ½ x 64 ½ inches Calder Foundation, Ne York Eucalyptus , 1940 Sheet metal, wire, and paint 94 ½ x 61 inches Calder Foundation, New York; Gift of Andréa Davidson, Shawn Davidson, Alexander S.C. -

The Museum of Modern Art for RELEASE: 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y

'/" The Museum of Modern Art FOR RELEASE: 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart December 19 , 1969 Press Preview December 18, 1969 1:00 p.m. - 4 p.m. A SALUTE TO ALEXANDER CALDER, an exhibition of 72 works from The Museum of Modern Art collection, illustrating the full range of Calder's art from the late 1920's to the present, will be on view at the Museum from December 19 through February 15. In ad dition to his world-famous stabiles and mobiles — hanging and standing and motorized, his most recent public monuments are represented, as well as early wire constructions, caricatures and wood sculptures, watercolors and drawings, prints and illustrated books, and jewelry. Among Calder's earliest sculptures in iron and brass wire on vi^w is the 39-inch figure of Josephine Baker (1927-29), inspired by the renowned American singer and dan cer then popular in Paris. Two life-size portrait heads, Marion Greenwood and Man with Eyeglasses, and several delightful miniature pieces, including a wire girl on a soda fountain stool, a wire cat lamp, and a tin elephant that makes a chair with the trunk holding a lamp, all date from the late '20's. The wood sculptures Horse (1928) and Shark Sucker (1930) and the classic metal mobiles Spider of 1939 and the suspended Snow Flurry of 1948 are included in the ex hibition. Also on view are three of his stabile constructions: Gibraltar (1936), Constellation (c. 1941), and Constellation with Red Object (1943). The celebrated Whale of 1937, originally a loan from the artist, which was al most continuously on view in the Museum's Sculpture Garden after 1941, was given to the collection by Calder in 1950. -

View the Saddlebred Sidewalk Brick List

American Saddlebred Museum !{r ,'. ; Saddlebred Sidewalk " i-^ - >\r\ '/ :. \"--l INSTALLATION HORSE DONOR CITY ST YEAR CH 2OTH CENTURY FOX MRS CHARLES E. GARRETT SAN ANTONIO TX 1989 A CHAMPAGNE TOAST AMERICANSADDLEBREDASSOCOF HARTLAND WI 2011 WISC A CONVERSATION PIECE MARION HUTCHESON ROSSVILLE GA 2014 A DAY IN THE PARK BRITTANY FOX CAMPBELL BIRMINGHAM AL 2018 A DAY IN THE SUN BETSY BOONE CONCORD NC 1 999 A DAY IN THE SUN BETSY YOUNG BOONE CONCORD NC 1 998 A KINDLING FLAME K Q CHEDESTER KNOXVILLE TN '1989 A LIKELY STORY MARION HUTCHESON ROSSVILLE GA 2014 A LITTLE IMAGINATION JILL BOSSHARD SUSSEX WI 2007 A LOTTA LOVIN' MERCEDES VANDORN & PHYL CLIVE IA 1 998 SHRADER CH A MAGIC SPELL MARY JANE GRALTON HARTLAND WI 2005 A MAGICAL CHOICE DOUGLAS & CLARA FLOR SHARPSBURG GA 2000 A NOTCH ABOVE SUSAN HAPP MEDINA OH 2016 A PLACE IN THE HEART KATIE RICHARDSON RANCHO SANTA FE CA 2000 A RARITY JEAN MCLEAN DAVIS HARRODSBURG KY 1 989 A RICH GIRL EL MILAGRO SALINAS CA '199'1-1994 A ROYAL QUEST FRANK&ANN STROUT CAPE ELIZABETH ME 1 996 A ROYAL OUEST ANN R STROUT CAPE ELIZABETH ME 2010 A SAVANNAH DAY DARRYL LEIFHEIT LEXINGTON KY 2019 A SENSATION JEAN MCLEAN DAVIS HARRODSBURG KY 1 989 A SENSATIONAL FOX CATHY LEE GREENVILLE SC 2002 A SONG IN MY HEART LAUREL NELSON BELLEVUE WA 2004 A SPECIAL EVENT SUSAN LUCAS MARQUETTE MI 1 989 A SPECIAL SURPRISE PAT JOHNSON GURNEE IL 1 998 A CH SUPREME SURPRISE ABIGAIL REISING ARLINGTON HEIGHTS IL 2001 CH A SWEET TREAT KIM COWART STATESVILLE NC 2000 CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE BRADLEY T ZIMMER WILMINGTON NC 1 991 -1 994 CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE KAREN WALDRON, BENT TREE FARIVI, SHAWSVILLE VA 1 989 LTD, A TOUCH OF PIZZAZZ SHANNON SEWELL ACWORTH GA 2006 A TOUCH OF RADIANCE ANDREA NELSON SANTA ROSA cA 1995 A TOUCH OF TENDERNESS JULIE & LORI SCHULTZ STEVENSVILLE Mr 1989 A TOUCH TOO MUCH DARRYL H. -

Calder-Release Final Feb 10

MoMA ANNOUNCES AN EXHIBITION CHARTING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ALEXANDER CALDER AND THE MUSEUM THROUGH WORKS AND ARCHIVAL MATERIALS IN ITS COLLECTION NEW YORK, February 11, 2020 [Updated February 10, 2021]—The Museum of Modern Art announces Alexander Calder: Modern from the Start, a focused look at one of the most wellknown and beloved artists of the 20th century through the lens of his relationship with MoMA. On view from March 14, 2021, through August 7, 2021, Alexander Calder: Modern from the Start will include approximately 70 artworks paired with film, historical photographs, and other archival materials drawn from MoMA’s collection and augmented by key loans from the Calder Foundation, New York. The exhibition is organized by Cara Manes, Associate Curator, with Zuna Maza and Makayla Bailey, Curatorial Fellows, Department of Painting and Sculpture. The exhibition will take as a point of departure the idea that Alexander Calder (American, 1898– 1976) assumed the unofficial role of the Museum’s “house artist” during its formative years. His work was first exhibited at MoMA in 1930, months after the institution opened its doors, and he was among only a handful of artists selected by the Museum’s founding director, Alfred H. Barr Jr., for inclusion in his two landmark 1936 exhibitions, Cubism and Abstract Art and Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. To inaugurate the then-new Goodwin and Stone Building in 1939, Calder was commissioned to make a hanging mobile for its interior “Bauhaus Staircase”; the resulting Lobster Trap and Fish Tail still hangs there today. Calder also worked closely with curator James Johnson Sweeney, in collaboration with artists Marcel Duchamp and Herbert Matter, on the checklist, catalogue, and installation of his major 1943 midcareer retrospective at MoMA, which introduced the artist, by then already known in Europe, to a broad American audience, through a survey of work made since his foundational years in the late 1920s living and working in Paris, at the heart of the international avantgarde.