FINAL REPORT Illicit Cigarette Trade Study in Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing West-Northern Provinces of Vietnam: Challenge to Integrate with GMS Market Via China-Laos-Vietnam Triangle Cooperation

CHAPTER 7 Developing West-Northern Provinces of Vietnam: Challenge to Integrate with GMS Market via China-Laos-Vietnam Triangle Cooperation Phi Vinh Tuong This chapter should be cited as: Phi, Vinh Tuong, 2012. “Developing West-Northern Provinces of Vietnam: Challenge to Integrate with GMS Market via China-Laos-Vietnam Triangle Cooperation.” In Five Triangle Areas in The Greater Mekong Subregion, edited by Masami Ishida, BRC Research Report No.11, Bangkok Research Center, IDE-JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand. CHAPTER 7 DEVELOPING WEST-NORTHEN PROVINCES OF VIETNAM: CHALLENGE TO INTEGRATE WITH GMS MARKET VIA CHINA-LAOS-VIETNAM TRIANGLE COOPERATION Phi Vinh Tuong INTRODUCTION The economy of Vietnam has benefited from regional and world markets over the past 20 years of integration. Increasing trade promoted investment, job creation and poverty reduction, but the distribution of trade benefits was not equal across regions. Some remote and mountainous areas, such as the west-northern region of Vietnam, were left at the margin. Even though they are important to the development of Vietnam, providing energy for industrialization, the lack of resource allocation hinders infrastructure development and, therefore, reduces their chances of access to regional and world markets. The initiative of developing one of the northern triangles, which consists of three west-northern provinces of Vietnam, the northern provinces of Laos and a southern part of Yunnan Province in China (we call the northern triangle as CHLV Triangle hereafter), could be a new approach for this region’s development. Strengthening the cooperation and specialization among these provinces may increase the chances of exporting local products with higher value added to regional markets, including the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) and south-western Chinese markets. -

Project SUN: a Study of the Illicit Cigarette Market In

Project SUN A study of the illicit cigarette market in the European Union, Norway and Switzerland 2017 Results Executive Summary kpmg.com/uk Important notice • This presentation of Project SUN key findings (the ‘Report’) has been prepared by KPMG LLP the UK member firm (“KPMG”) for the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (RUSI), described in this Important Notice and in this Report as ‘the Beneficiary’, on the basis set out in a private contract dated 27 April 2018 agreed separately by KPMG LLP with the Beneficiary (the ‘Contract’). • Included in the report are a number of insight boxes which are written by RUSI, as well as insights included in the text. The fieldwork and analysis undertaken and views expressed in these boxes are RUSI’s views alone and not part of KPMG’s analysis. These appear in the Foreword on page 5, the Executive Summary on page 6, on pages 11, 12, 13 and 16. • Nothing in this Report constitutes legal advice. Information sources, the scope of our work, and scope and source limitations, are set out in the Appendices to this Report. The scope of our review of the contraband and counterfeit segments of the tobacco market within the 28 EU Member States, Switzerland and Norway was fixed by agreement with the Beneficiary and is set out in the Appendices. • We have satisfied ourselves, so far as possible, that the information presented in this Report is consistent with our information sources but we have not sought to establish the reliability of the information sources by reference to other evidence. -

The Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products and How to Tackle It Disclaimer and Statement of Purpose

The Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products and How to Tackle It Disclaimer and Statement of Purpose “The Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products and How to Tackle It” is published by the International Tax and Investment Center (ITIC), a non-profit research and education foundation. ITIC serves as a clearinghouse for information on best practices in taxation and investment policy, and as a training center to transfer such know how to improve the investment climates of transition and developing countries, thereby spurring formation and development of business and economic prosperity. The purpose of this publication is to serve as a resource guide and best practices reference for tax, customs, and law enforcement officials to improve their efforts to combat the illicit trade in tobacco products. ITIC received supplemental contributions from tobacco companies to help underwrite the cost of this publication. However, ITIC retained full editorial control and takes full responsibility for the content and any errors or omissions. The publication is not intended to be a statement of ITIC policies, nor is it intended to endorse the views or policies of any of the contributing organizations or individuals (financially or otherwise), such as the World Customs Organization (WCO), the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) or the tobacco industry. Inputs to this publication, including data and case studies, were provided by tax and customs officials, the World Customs Organization (WCO), industry representatives and various consultants. About the Author Elizabeth -

Tobacco Labelling -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

Council Directive 89/622/EC concerning the labelling of tobacco products, as amended TAR AND NICOTINE CONTENTS OF THE CIGARETTES SOLD ON THE EUROPEAN MARKET AUSTRIA Brand Tar Yield Nicotine Yield Mg. Mg. List 1 A3 14.0 0.8 A3 Filter 11.0 0.6 Belvedere 11.0 0.8 Camel Filters 14.0 1.1 Camel Filters 100 13.0 1.1 Camel Lights 8.0 0.7 Casablanca 6.0 0.6 Casablanca Ultra 2.0 0.2 Corso 4.0 0.4 Da Capo 9.0 0.4 Dames 9.0 0.6 Dames Filter Box 9.0 0.6 Ernte 23 13.0 0.8 Falk 5.0 0.4 Flirt 14.0 0.9 Flirt Filter 11.0 0.6 Golden Smart 12.0 0.8 HB 13.0 0.9 HB 100 14.0 1.0 Hobby 11.0 0.8 Hobby Box 11.0 0.8 Hobby Extra 11.0 0.8 Johnny Filter 11.0 0.9 Jonny 14.0 1.0 Kent 10.0 0.8 Kim 8.0 0.6 Kim Superlights 4.0 0.4 Lord Extra 8.0 0.6 Lucky Strike 13.0 1.0 Lucky Strike Lights 9.0 0.7 Marlboro 13.0 0.9 Marlboro 100 14.0 1.0 Marlboro Lights 7.0 0.6 Malboro Medium 9.0 0.7 Maverick 11.0 0.8 Memphis Classic 11.0 0.8 Memphis Blue 12.0 0.8 Memphis International 13.0 1.0 Memphis International 100 14.0 1.0 Memphis Lights 7.0 0.6 Memphis Lights 100 9.0 0.7 Memphis Medium 9.0 0.6 Memphis Menthol 7.0 0.5 Men 11.0 0.9 Men Light 5.0 0.5 Milde Sorte 8.0 0.5 Milde Sorte 1 1.0 0.1 Milde Sorte 100 9.0 0.5 Milde Sorte Super 6.0 0.3 Milde Sorte Ultra 4.0 0.4 Parisienne Mild 8.0 0.7 Parisienne Super 11.0 0.9 Peter Stuyvesant 12.0 0.8 Philip Morris Super Lights 4.0 0.4 Ronson 13.0 1.1 Smart Export 10.0 0.8 Treff 14.0 0.9 Trend 5.0 0.2 Trussardi Light 100 6.0 0.5 United E 12.0 0.9 Winston 13.0 0.9 York 9.0 0.7 List 2 Auslese de luxe 1.0 0.1 Benson & Hedges 12.0 1.0 Camel 15.0 1.0 -

REPORTING INSTRUMENT 1. Origin of the Report

REPORTING INSTRUMENT 1. Origin of the report Help Question 1 is mandatory Republic of Korea (a) Name of Contracting Party Help (b) Information on National Contact/Focal Point Help Name and title of contact officer Hee Joo Choi, Director General of Bureau of Health Policy, Ministry of Health and Welfare Mailing address Anyang Construction Tower 10F, 1112-1, Daran- Dong, Dongan-Gu, Anyang, Gyunggi, Republic of Korea, 431-811 Telephone number 82-31-440-9101 Fax number 82-31-440-9069 E-mail [email protected] (c) Information on contact officer submitting the national report if different from the above Help Name and title of contact officer Hong Seok Choi, Director of Health Promotion Division, Ministry of Health and Welfare Mailing address Anyang Construction Tower 10F, 1112-1, Daran- Dong, Dongan-Gu, Anyang, Gyunggi, Republic of Korea, 431-811 Telephone number 82-31-440-9138 Fax number 82-31-440-9142 E-mail [email protected] (d) Signature of the officer responsible for submitting report Help Name and title of officer Han Hee Lee, Deputy Director Full name of the institution Health Promotion Division, Ministry of Health and Welfare Mailing address Anyang Construction Tower 10F, 1112-1, Daran- Dong, Dongan-Gu, Anyang, Gyunggi, Republic of Korea, 431-811 Telephone number 82-31-440-9139 Fax number 82-31-440-9142 E-mail [email protected] Web page 15/8/2005-15/8/2007 (e) Period reported Help 31/8/2007 (f) Date the report was submitted Help 2. Demographics Help Create Age Group (a) Age and sex: Help Question 2(a) is mandatory Year Percentage of Percentage Percentage of Age groups male of female total (latest available) population population population 2005 13-15 4.37 3.89 4.13 2005 16-17 2.66 2.44 2.55 2005 19-24 9.39 8.85 9.12 2005 25-34 17.32 16.52 16.92 2005 35-44 17.90 17.33 17.62 2005 45-54 14.28 14.09 14.18 2005 55-64 8.44 9.00 8.72 2005 65+ 7.17 10.99 9.07 Create Ethnic Group (b) Ethnicity (optional): Help Question 2(b) is optional Name of ethnic group Percentage of total population 3. -

Tobacco Use Disorder and Treatment: New Challenges and Opportunities

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS Open Access Articles Open Access Publications by UMMS Authors 2017-09-01 Tobacco use disorder and treatment: new challenges and opportunities Douglas Ziedonis University of California - San Diego Et al. Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/oapubs Part of the Behavior and Behavior Mechanisms Commons, Neuroscience and Neurobiology Commons, and the Substance Abuse and Addiction Commons Repository Citation Ziedonis D, Das S, Larkin C. (2017). Tobacco use disorder and treatment: new challenges and opportunities. Open Access Articles. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/oapubs/3255 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Articles by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Clinical research Tobacco use disorder and treatment: new challenges and opportunities Douglas Ziedonis, MD, MPH; Smita Das, MD, PhD, MPH; Celine Larkin, PhD Introduction obacco use is the cause of over 5 million deaths perT year globally,1 over twice as many deaths due to al- cohol and illicit drugs combined. If current consump- tion rates continue, tobacco is projected to kill 1 billion people this century, with the majority of deaths occur- ring in low- and middle-income countries,2 although there is good evidence for the effectiveness both of pol- Tobacco use remains a global problem, and options for consumers have increased with the development and mar- keting of e-cigarettes and other new nicotine and tobacco products, such as “heat-not-burn” tobacco and dissolv- able tobacco. -

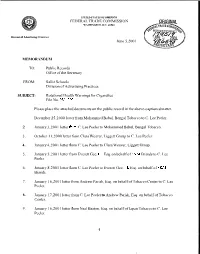

Rotational Health Warnings for Cigarettes File No

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D C. 20580 Division of Advertising Practices June 5,2001 MEMORANDUM TO: Public Records Office of the Secretary FROM: Sallie Schools Division of Advertising Practices SUBJECT: Rotational Health Warnings for Cigarettes File No. Please place the attached documents on the public record in the above-captioned matter. December 25,2000 letter from Mohammed Babul, Bengal Tobacco to C. Lee Peeler. 2. January 3,2001 letter C. Lee Peeler to Mohammed Babul, Bengal Tobacco. 3. October 11,2000 letter fiom Clara Weaver, Liggett Group to C. Lee Peeler. 4. January 4,2001 letter fkom C. Lee Peeler to Clara Weaver, Liggett Group. 5. January 5,2001 letter from Everett Gee, Esq. on behalf of Brands to C. Lee Peeler. 6. January 8,2001 letter fkom C. Lee Peeler to Everett Gee, Esq. on behalf of Brands. 7. January 16,2001 letter from Andrew Parish, Esq. on behalf of Tobacco Center to C. Lee Peeler. 8. January 17,2001 letter from C. Lee Peeler to Andrew Parish, Esq. on behalf of Tobacco Center. 9. January 16,2001 letter fkom Neal Beaton, Esq. on behalf of Japan Tobacco to C. Lee Peeler. 1 Records June 5,2001 Page 2 10. January 19,2001 letter fiom C. Lee Peeler to Neal Beaton, Esq. on behalf of Japan Tobacco. 11. January 10,2001 letter Thomas O’Connell, Sun Tobacco to C. Lee Peeler. 12. January 22,2001 letter from C. Lee Peeler to Thomas O’Connell, Sun Tobacco. 13. January 18,2001 letter fiom Kris Hewitt, Tobacco to C. -

Vietnam Business: Vietnam Development Report 2006 Report Business: Development Vietnam Vietnam Report No

Report No. 34474-VNReport No. Vietnam 34474-VN Vietnam Development Business: Report 2006 Vietnam Business Vietnam Development Report 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized November 30, 2005 Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit East Asia and Pacific Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized IMF International Monetary Fund JBIC Japan Bank for International Cooperation JSB Joint Stock Bank JSC Joint Stock Company LDIF Local Development Investment Fund LEFASO Vietnam Leather and Footwear Association LUC Land-Use Right Certificate MARD Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development MDG Millennium Development Goal MOC Ministry of Construction MOET Ministry of Education and Training MOF Ministry of Finance MOH Ministry of Health MOHA Ministry of Home Affairs MOI Ministry of Industry MOLISA Ministry of Labor, Invalids and Social Affairs MONRE Ministry ofNatural Resources and the Environment MOT Ministry of Transport MPDF Mekong Private Sector Development Facility MPI Ministry of Planning and Investment NBIC National Business Information Center NGO Non-Governmental Organization NOIP National Office for Intellectual Property NPL Non-Performing Loan NPV Net Present Value ODA Official Development Assistance OOG Office of Government OSS One-Stop Shop PCF People’s Credit Fund PCI Provincial Competitiveness Index PER-IFA Public Expenditure Review-Integrated -

World Bank Document

HNP DISCUSSION PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Economics of Tobacco Control Paper No. 23 Russia (Moscow) 1999 Global Youth Tobacco Survey: About this series... This series is produced by the Health, Nutrition, and Population Family (HNP) of the World Bank’s Human Development Network. The papers in this series aim to provide a vehicle for publishing preliminary and unpolished results on HNP topics to encourage discussion and Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Economic Aspects debate. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author(s) and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. Citation and the use of material presented in this series should take into account this provisional character. For free copies of papers in this series please contact the individual authors whose name appears on the paper. Hana Ross Enquiries about the series and submissions should be made directly to the Editor in Chief Alexander S. Preker ([email protected]) or HNP Advisory Service ([email protected], tel 202 473-2256, fax 202 522-3234). For more information, see also www.worldbank.org/hnppublications. The Economics of Tobacco Control sub-series is produced jointly with the Tobacco Free Initiative of the World Health Organization. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized manner to the World Health Organization or to the World Bank, their affiliated organizations or members of their Executive Boards or the countries they represent. -

Participating Manfacturers' Brands Approved for Sale

Participating Manufacturers' Brands Brand Family Brand Code Manufacturer 1839 000270 PREMIER MANUFACTURING, INC. 1839 (RYO) 000271 PREMIER MANUFACTURING, INC. 1ST CLASS 000171 PREMIER MANUFACTURING, INC. ACE 000080 KING MAKER MARKETING INC AMERICAN BISON 000292 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC AMERICAN BISON (RYO) 000293 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC BALI SHAG (RYO) 000013 TOP TOBACCO LP BARON AMERICAN BLEND 000064 FARMERS TOBACCO CO OF CYNTHIANA INC BASIC 000149 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC BENSON & HEDGES 000150 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC BLACK & GOLD 000227 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD BUGLER (RYO) 000595 SCANDINAVIAN TOBACCO GROUP LANE LIMITED CAMBRIDGE 000152 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC CAMEL 000185 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CAMEL WIDES 000186 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CANOE (RYO) 000294 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC CAPRI 000187 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CARLTON 000188 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CHECKERS 000081 KING MAKER MARKETING INC CHESTERFIELD 000154 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC CIGARETTELLOS 000228 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD CLASSIC 000229 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD CROWNS 000593 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC CUSTOM BLENDS (RYO) 000295 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC DAVE'S 000620 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC DAVIDOFF 000014 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC DORAL 000189 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY DREAMS 000628 KRETEK INTERNATIONAL INC. July 26, 2021 Page 1 of 4 Brand Family Brand Code Manufacturer DRUM (RYO) 000260 TOP TOBACCO LP DUNHILL 000190 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY DUNHILL INTERNATIONAL 000191 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY EAGLE 20'S 000277 VECTOR TOBACCO INC D/B/A MEDALLION BRANDS ECLIPSE 000192 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY EVE 000105 LIGGETT GROUP LLC FANTASIA 000230 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD FORTUNA 000015 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC GAMBLER (RYO) 000261 TOP TOBACCO LP GAULOISES 000016 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC GITANES 000017 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC GOLD CREST 000083 KING MAKER MARKETING INC GPC 000194 R.J. -

Tobacco Directory Deletions by Manufacturer

Cigarettes and Tobacco Products Removed From The California Tobacco Directory by Manufacturer Brand Manufacturer Date Comments Removed Catmandu Alternative Brands, Inc. 2/3/2006 Savannah Anderson Tobacco Company, LLC 11/18/2005 Desperado - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 Peace - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 Revenge - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 The Brave Bekenton, S.A. 6/2/2006 Barclay Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Belair Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Private Stock Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Raleigh Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/6/2005 2004 Viceroy Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/3/2010 2004 Coronas Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Palace Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Record Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 VL Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Freemont Caribbean-American Tobacco Corp. 5/2/2008 Kingsboro Carolina Tobacco Company 5/3/2010 Roger Carolina Tobacco Company 5/3/2010 Aura Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Cheyenne Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Cheyenne - RYO Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Decade Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Bridgeton CLP, Inc. 5/4/2007 DT Tobacco - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Railroad - RYO CLP, Inc. 5/30/2008 Smokers Palace - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Smokers Select - RYO CLP, Inc. 5/30/2008 Southern Harvest - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Davidoff Commonwealth Brands, Inc. 7/19/2016 Malibu Commonwealth Brands, Inc. 5/31/2017 McClintock - RYO Commonwealth Brands, Inc. -

Viet Nam Central Committee for Flood and Storm Control VIET NAM COUNTRY REPORT

Viet Nam Central Committee for Flood and Storm Control VIET NAM COUNTRY REPORT By: Mr. Nguyen Ngoc Dong, Director, Disaster Management Centre DEPARTMENT OF DYKE MANAGEMENT AND FLOOD AND STORM CONTROL CONTENTS 1. Flood and Typhoon Situation * 2. Damage caused by the storms and flood (up to 31 December 1998) * 3. Actions taken to Guide, to Respond to, and to Combat the Effects of the Floods and Storms * In 1998, Viet Nam suffered a number of severe disasters. Most notable were the serious summer drought and the severe flooding in Central Viet Nam which resulted from Tropical Storms Babs, Chip, Dawn, Faith, and Elvis, causing tremendous loss of life and property damage. In this report we will concentrate on the flood disaster that occurred in the Central and Central Highlands Provinces of Viet Nam. 1. Flood and Typhoon Situation From November to December 1998, Storms Nos. 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 struck the Central and Central Highlands Provinces of Vietnam in succession. The storms combined with a cold front from the North and high tides to cause heavy rain in coastal provinces from Quang Binh to Binh Thuan and in the Central Highlands. Average rainfall was measured at about 200 to 600 mm, while at A Luoi (in Thua Thien Hue), as well as at Tra My, Xuan Binh, and Tien Phuoc (in Quang Nam-Da Nang) rainfall averaged 800 to 1,200 mm. Rain over a large area raised the water levels on rivers from Quang Tri Province to Khanh Hoa Province above Alarm Level III (the highest Vietnamese flood-disaster Alarm Level designation).