Stop Making Sense As a Postmodern Artifact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology Fa Ct Or

Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price Origin Label Genre Release A40355 A & P Live In Munchen + Cd 2 Dvd € 24 Nld Plabo Pun 2/03/2006 A26833 A Cor Do Som Mudanca De Estacao 1 Dvd € 34 Imp Sony Mpb 13/12/2005 172081 A Perfect Circle Lost In the Bermuda Trian 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Virgi Roc 29/04/2004 204861 Aaliyah So Much More Than a Woman 1 Dvd € 19 Eu Ch.Dr Doc 17/05/2004 A81434 Aaron, Lee Live -13tr- 1 Dvd € 24 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81435 Aaron, Lee Video Collection -10tr- 1 Dvd € 22 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81128 Abba Abba 16 Hits 1 Dvd € 20 Nld Univ Pop 22/06/2006 566802 Abba Abba the Movie 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 29/09/2005 895213 Abba Definitive Collection 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 22/08/2002 824108 Abba Gold 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 21/08/2003 368245 Abba In Concert 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 25/03/2004 086478 Abba Last Video 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Univ Pop 15/07/2004 046821 Abba Movie -Ltd/2dvd- 2 Dvd € 29 Nld Polar Pop 22/09/2005 A64623 Abba Music Box Biographical Co 1 Dvd € 18 Nld Phd Doc 10/07/2006 A67742 Abba Music In Review + Book 2 Dvd € 39 Imp Crl Doc 9/12/2005 617740 Abba Super Troupers 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 14/10/2004 995307 Abbado, Claudio Claudio Abbado, Hearing T 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Tdk Cls 29/03/2005 818024 Abbado, Claudio Dances & Gypsy Tunes 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 12/12/2001 876583 Abbado, Claudio In Rehearsal 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 23/06/2002 903184 Abbado, Claudio Silence That Follows the 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 5/09/2002 A92385 Abbott & Costello Collection 28 Dvd € 163 Eu Univ Com 28/08/2006 470708 Abc 20th Century Masters -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

An Uncurling Hand Isolation in Public Places

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2011 An Uncurling Hand Isolation In Public Places Kimberly Kelley Lundblom University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lundblom, Kimberly Kelley, "An Uncurling Hand Isolation In Public Places" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1761. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1761 AN UNCURLING HAND: ISOLATION IN PUBLIC PLACES by KIMBERLY KELLEY LUNDBLOM B.A. University of North Florida, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2011 Major Professor: Terry Thaxton © 2011 Kimberly K. Lundblom ii ABSTRACT The creative thesis ―An Uncurling Hand: Isolation in Public Places‖ is a collection of poetry concerned with ideological dichotomies: conventional domestication against the exotic, class divides and its implications for identity, and most importantly the feeling of isolation even when surrounded by others. iii I am grateful to Terry Thaxton, whose belief in my abilities was unwavering and life altering. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Writing Life Essay ............................................................................................................ -

Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet

Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet Moritz Neumüller Wien, Oktober 2001 DOKTORAT DER SOZIAL- UND WIRTSCHAFTSWISSENSCHAFTEN 1. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Wolfgang Panny, Institut für Informationsver- arbeitung und Informationswirtschaft der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, Abteilung für Angewandte Informatik. 2. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Herbert Hrachovec, Institut für Philosophie der Universität Wien. Betreuer: Gastprofessor Univ. Doz. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Veith Risak Eingereicht am: Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Sozial- und Wirtschaftswissenschaften an der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien eingereicht bei 1. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Panny, Institut für Informationsverarbeitung und Informationswirtschaft der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, Abteilung für Angewandte Informatik 2. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Herbert Hrachovec, Institut für Philosophie der Universität Wien Betreuer: Gastprofessor Univ. Doz. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Veith Risak Fachgebiet: Informationswirtschaft von MMag. Moritz Neumüller Wien, im Oktober 2001 Ich versichere: 1. daß ich die Dissertation selbständig verfaßt, andere als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt und mich auch sonst keiner unerlaubten Hilfe bedient habe. 2. daß ich diese Dissertation bisher weder im In- noch im Ausland (einer Beurteilerin / einem Beurteiler zur Begutachtung) in irgendeiner Form als Prüfungsarbeit vorgelegt habe. 3. daß dieses Exemplar mit der beurteilten Arbeit überein -

Note: the Following List Is Only a Sampling of the Songs That Best Describe the Joker’S Wild

Note: The following list is only a sampling of the songs that best describe The Joker’s Wild. This is not an all-inclusive listing. The Joker’s Wild welcomes requests and music from a variety of genres. Ain't That A Kick In The Head Jump, Jive, an' Wail All of Me Just a Gigolo/I Ain't Got Nobody All The Way Just One of Those Things Angel Eyes Kansas City Angelina/Zooma-Zooma Kiss To Build a Dream On, A Are You Havin' Any Fun Lady is a Tramp, The As Long As I'm Singin' Let's Call The Whole Thing Off As Time Goes By Let's Fall in Love At Last Like Young Auld Lang Syne L-O-V-E Baby Please Come Home Love is the Tender Trap Banana Split For My Baby Luck Be a Lady Basin Street Blues Mack the Knife Besame Mucho Memories Are Made of This Best Is Yet To Come Moon River Beyond the Sea Moonlight in Vermont Bim Bam Moonlight Serenade Bla Bla Cha Cha Cha More Blue Alert Mustang Sally Buona Sera My Funny Valentine Can't Take That Away From Me New York, New York Cheek to Cheek Night and Day Come Fly With Me A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square Come Rain or Come Shine O Sole Mio Comin' Home Baby Oh Marie Crazy Lady Old Devil Moon Dig That Crazy Chick One For My Baby Do Nothin' Till Hear From Me Papa Loves Mambo Don't Get Around Much Anymore Paper Moon Down The Road I Go Pennies From Heaven Duke's Place Please Be Kind East of the Sun, West of the Moon Please Don't Talk About Me When I'm Gone Easy To Love Pop-A-Diddy Fifteen on Fifteen Shadow of Your Smile, The Fine Romance, A Shape in a Drape Five Guys Named Moe Sing, Sing, Sing Five Months, Two Weeks, -

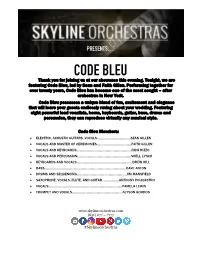

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat. -

Set List Select Several Songs to Be Played at Your Event / Party

FORM: SET LIST SELECT SEVERAL SONGS TO BE PLAYED AT YOUR EVENT / PARTY SONGS YOU CAN EAT AND DRINK TO MEDLEYS SONGS YOU CAN DANCE TO ELO - Mr. Blue Sky Lykke Li - I follow Rivers St. Vincent - Digital Witness Elton John - Tiny Dancer Major Lazer – Lean On Stealers Wheel - Stuck in the Middle With You Beach Boys - God Only Knows Daft Punk Medley Adele - Rolling in the Deep Empire of the Sun - Walking On a Dream Mariah Carey - Fantasy Steely Dan - Hey Nineteen Belle and Sebastian - Your Covers Blown 90's R&B Medley Amy Winehouse - Valerie Feist - 1,2,3,4 Mark Morrison - Return of the Mack Steely Dan - Peg Black Keys - Gold On the Ceiling TLC Ariel Pink - Round + Round Feist - Sea Lion Woman Mark Ronson - Uptown Funk Stevie Nicks - Stand Back Bon Iver – Holocene Usher Beach Boys - God Only Knows Fleetwood Mac - Dreams Marvin Gaye - Ain't No Mountain High Enough Stevie Wonder - Higher Ground Bon Iver - Re: Stacks Montell Jordan Beck - Debra Fleetwood Mac - Never Going Back MGMT - Electric Feel Stevie Wonder - Sir Duke Bon Iver - Skinny Love Mark Morrison Beck - Where It’s At Fleetwood Mac - Say You Love Me Michael Jackson - Human Nature Stevie Wonder- Superstition Christopher Cross - Sailing Next Belle and Sebastian - Your Covers Blown Fleetwood Mac - You Make Lovin Fun Michael Jackson - Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough Supremes - You Can't Hurry Love David Bowie - Ziggy Stardust 80's Pop + New Wave Medley Billy Preston - Nothing From Nothing Frank Ocean – Lost Michael Jackson - Human Nature Talking Heads - Burning Down the House Eagles - Hotel California New Order Black Keys - Gold On the Ceiling Frankie Vailli - December 1963 (Oh What A Night) Michael Jackson - O The Wall Talking Heads - Girlfriend is Better ELO - Mr. -

P.O.V. 19S Discussion Guide Kokoyakyu: High School Baseball a Film by Kenneth Eng

n o s a e P.O.V. 19S Discussion Guide Kokoyakyu: High School Baseball A Film by Kenneth Eng www.pbs.org/pov P.O.V. n o s Discussion Guide | Kokoyakyu: High School Baseball a e 19S Letter from the Filmmaker NEW YORK, SPRING 2006 Dear Colleague, It started back in January of 2001 while we were working in India on the Projectile Arts documentary Take Me to the River, about a phenomenal Hindu gathering. We wanted to make another film with Projectile Arts that would bring an inspiring cultural experience to America. Surrounded by 20 million Hindu pilgrims at the world’s largest religious festival, the “Kumbh Mela,” our thoughts naturally turned to baseball (we both grew up in Boston as hopeless Red Sox fans). Ichiro Suzuki was about to become the first Japanese position player in Major League history. We were fascinated — the whole idea of Japanese baseball was so mysterious to many Americans, and we knew it could be a great window into Japanese culture. Director Kenneth Eng Of course, Ichiro’s first season in the Majors Photo courtesy of Kenneth Eng turned out to be one for the record books — on top of the personal achievements (the batting title, the Gold Glove, the Rookie of the Year award, and Most Valuable Player), Ichiro led his team to an American League record 116 wins. We discovered Robert Whiting’s book You Gotta Have Wa and learned for the first time about Japan’s National High School Baseball Tournament, known as the Koshien Tournament for its famous stadium. -

Postmodern Test Theory

Postmodern Test Theory ____________ Robert J. Mislevy Educational Testing Service ____________ (Reprinted with permission from Transitions in Work and Learning: Implications for Assessment, 1997, by the National Academy of Sciences, Courtesy of the National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.) Postmodern Test Theory Robert J. Mislevy Good heavens! For more than forty years I have been speaking prose without knowing it. Molière, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme INTRODUCTION Molière’s Monsieur Jourdan was astonished to learn that he had been speaking prose all his life. I know how he felt. For years I have just been doing my job— trying to improve educational assessment by applying ideas from statistics and psychology. Come to find out, I’ve been advancing “neopragmatic postmodernist test theory” without ever intending to do so. This paper tries to convey some sense of what this rather unwieldy phrase means and offers some thoughts about what it implies for educational assessment, present and future. The goods news is that we can foresee some real improvements: assessments that are more open and flexible, better connected with students’ learning, and more educationally useful. The bad news is that we must stop expecting drop-in-from-the-sky assessment to tell us, in 2 hours and for $10, the truth, plus or minus two standard errors. Gary Minda’s (1995) Postmodern Legal Movements inspired the structure of what follows. Almost every page of his book evokes parallels between issues and new directions in jurisprudence on the one hand and the debates and new developments in educational assessment on the other. Excerpts from Minda’s book frame the sections of this paper. -

Poststructuralism, Cultural Studies, and the Composition Classroom: Postmodern Theory in Practice Author(S): James A

Poststructuralism, Cultural Studies, and the Composition Classroom: Postmodern Theory in Practice Author(s): James A. Berlin Source: Rhetoric Review, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Autumn, 1992), pp. 16-33 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/465877 Accessed: 13-02-2019 19:20 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/465877?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Rhetoric Review This content downloaded from 146.111.138.234 on Wed, 13 Feb 2019 19:20:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JAMES A. BERLIN - ~~~~~~~~~~~~~Purdue University Poststructuralism, Cultural Studies, and the Composition Classroom: Postmodern Theory in Practice The uses of postmodern theory in rhetoric and composition studies have been the object of considerable abuse of late. Figures of some repute in the field-the likes of Maxine Hairston and Peter Elbow-as well as anonymous voices from the Burkean Parlor section of Rhetoric Review-most recently, TS, a graduate student, and KF, a voice speaking for "a general English teacher audience" (192)-have joined the chorus of protest. -

Media Theory and Semiotics: Key Terms and Concepts Binary

Media Theory and Semiotics: Key Terms and Concepts Binary structures and semiotic square of oppositions Many systems of meaning are based on binary structures (masculine/ feminine; black/white; natural/artificial), two contrary conceptual categories that also entail or presuppose each other. Semiotic interpretation involves exposing the culturally arbitrary nature of this binary opposition and describing the deeper consequences of this structure throughout a culture. On the semiotic square and logical square of oppositions. Code A code is a learned rule for linking signs to their meanings. The term is used in various ways in media studies and semiotics. In communication studies, a message is often described as being "encoded" from the sender and then "decoded" by the receiver. The encoding process works on multiple levels. For semiotics, a code is the framework, a learned a shared conceptual connection at work in all uses of signs (language, visual). An easy example is seeing the kinds and levels of language use in anyone's language group. "English" is a convenient fiction for all the kinds of actual versions of the language. We have formal, edited, written English (which no one speaks), colloquial, everyday, regional English (regions in the US, UK, and around the world); social contexts for styles and specialized vocabularies (work, office, sports, home); ethnic group usage hybrids, and various kinds of slang (in-group, class-based, group-based, etc.). Moving among all these is called "code-switching." We know what they mean if we belong to the learned, rule-governed, shared-code group using one of these kinds and styles of language. -

Talking Heads -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

Talking Heads / David Byrne / A+ A B+ B C D updated: 09/06/2005 Tom Tom Club / Jerry Harrison / ARTISTS = Artists I´m always looking to trade for new shows not on my list :-) The Heads DVD+R for trade: (I´ll trade 1 DVD+R for 2 CDRs if you haven´t a DVD I´m interested and you still would like to tarde for a DVD+R before contact me here are the simple rules of trading policy: - No trading of official released CD´s, only bootleg recordings, - Please use decent blanks. (TDK, Memorex), - I do not sell any bootleg or copies of them from my list. Do not ask!! - I send CDRs only, no tapes, Trading only !!! ;-), - I don't do blanks & postage or 2 for 1's; fair trading only (CD for a CD or CD for a tape), I trade 1 DVD+R for 2 CDRs if you haven´t a DVD I´m - Pack well, ship airmail interested - CD's should be burned DAO, without 2 seconds gaps between the - Don´t send Jewel Cases, use plastic or paper pockets instead, I´ll do the same tracks, - For set lists or quality please ask, - No writing on the disks please - Please include a set list or any venue info, I´l do the same, - Keep contact open during trade to work out a trade please contact me: [email protected] TERRY ALLEN Stubbs, Austin, TX 1999/03/21 Audience Recording (feat. David Byrne) CD Amarillo Highway / Wilderness Of This World / New Delhi Freight Train / Cortez Sail / Buck Naked (w/ David Byrne) / Bloodlines I / Gimme A Ride To Heaven Boy DAVID BYRNE In The Pink Special --/--/-- TV-broadcast / documentary DVD+R Interviews & music excerpts TV-Show Appearances 1990 - 2004 TV-broadcasts (quality differs on each part) DVD+R I.