(And) Black Music: a Legacy of Unequal Protection K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merchant, Jimmy Merchant, Jimmy

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Oral Histories Bronx African American History Project 4-7-2006 Merchant, Jimmy Merchant, Jimmy. Interview: Bronx African American History Project Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_oralhist Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Merchant, Jimmy. 7 April 2006. Interview with the Bronx African American History Project. BAAHP Digital Archive at Fordham. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Bronx African American History Project at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interviewee: Jimmy Merchant Interviewers: Alessandro Buffa, Loreta Dosorna, Dr. Brian Purnell, and Dr. Mark Naison Date: April 7, 2006 Transcriber: Samantha Alfrey Mark Naison (MN): This is the 154th interview of the Bronx African American History Project. We are here at Fordham University on April 7, 2006 with Jimmy Merchant, an original and founding member of Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, who has also had a career as an artist. And with us today, doing the interviews, are Alessandro Buffa, Lorreta Dosorna, Brian Purnell, and Mark Naison. Jimmy, can you tell us a little about your family and where they came from originally? Jimmy Merchant (JM): My mom basically came from Philadelphia. My dad – his family is from the Bahamas. He – my dad – was shifted over to the south as a youngster. His mother was from the Bahamas and she moved into the South – South Carolina, something like that – and he grew up there. -

Black Pearls

Number 22 The Journal of the AMERICAN BOTANI CAL COUNCU.. and the HERB RESEARCH FOUNDATION Hawthorn -A Literature Review Special Report: Black Pearls - Prescription Drugs Masquerade as Chinese Herbal Arthritis Formula FROM THE EDITOR In This Issue his issue of HerbalGram offers some good news and some herbal combination for use in rheumatoid arthritis and related bad news. First the good news. Our Legal and Regulatory inflammatory conditions, this product has been tested repeatedly Tsection is devoted to a recent clarification by the Canadian and shown positive for the presence of unlabeled prescription drugs. Health Protection Branch (Canada's counterpart to our FDA)of its Herb Research Foundation President Rob McCaleb and I have willingness to grant "Traditional Medicine" status to many medici spent several months researching the latest resurgence in sales of nal herb products sold in Canada under the already existing approval this and related products. We have made every attempt to follow up process for over-the-counter remedies. This announcement has on many avenues to determine whether these products contain un been hailed as a positive step by almost everyone with whom we labeled drugs, and whether or not they are being marketed fraudu have talked, both in academia and in the herb industry. lently. Herb marketers and consumers alike should be concerned More good news is found in the literature review on Hawthorn. whenever prescription drugs are presented for sale as "natural" and Steven Foster has joined Christopher Hobbs in preparing a compre "herbal." You will find our report on page 4. hensive view of a plant with a long history of use as both food and In addition, we present the usual array of interesting blurbs, medicine. -

Music I Begins at 9 P.M

26 Greenfield Recorder, Thursday, April 25, 198S • £ A Ifilllil ii ) Leisure Calendar is a free public service provided by ________ shop, "The Old Maid and the Thief," by Gian Carolo Me-* the Greenfield Recorder for its readers. notti. 8 p.m. Recital Hall, Arts Center on Brickyard Pond- Individuals and organizations are invited to submit infor Free admission. mation for publical.on. All material must include: date, time, location, admission price, sponsor and a brief de scription of the event. Deadline is 10 days before publica Dance tion date. Events must be open to the public. Photographs I are welcome and should be black-and-white glossies. Be THE MONADNOCK FOLKLORE SOCIETY sponsors *\ sure to include proper identification on photos. If you contra dance in Greenfield (N.H.) Town Hall, 8 to 11:30c would like your photo returned, enclose a self-addressed p.m. Potluck supper at 7 p.m. Beginners welcome. Ad-r stamped envelope. mission $3. \ Send information, to: Leisure Calendar, Greenfield Re corder, 14 Hope St., Greenfield, Mass. 01301 or call 772- i 0261 (Ext. 316). Films Because space varies from week to week, we regret that we cannot guarantee that all listings will be printed. ACTOR'S THEATER, 2 Flat St., BratUeboro, Vt.; "A Boy- and His Dog," 197S underground science-fiction film ocu survival after nuclear war. Latchis Ballroom, 7 p.m./, Continues April 28 and May 4 and 5. >; -rfc Clubs * CALVIN'S, Fiske Avenue, Greenfield: The Mix. Music I begins at 9 p.m. $2 cover charge. ST AGE WEST: "The Good Doctor," by Neil Simon. -

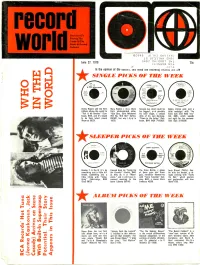

Record World

record tWODedicated To Serving The Needs Of The Music & Record Industry x09664I1Y3 ONv iS Of 311VA ZPAS 3NO2 ONI 01;01 3H1 June 21, 1970 113N8V9 NOti 75c - In the opinion of the eUILIRS,la's wee% Tne itmuwmg diCtie SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK EPIC ND ARMS CAN EVER HOLD YOU CORBYVINTON Kenny Rogers and the First Mary Hopkin sings Doris Nilsson has what could be Bobby Vinton gets justa Edition advise the world to Day'sphilosophicaloldie, his biggest, a n dpossibly littlenostalgicwith"No "TellItAll Brother" (Sun- "Que Sera, Sera (Whatever hisbest single,a unique Arms Can Ever Hold You" beam, BMI), and it's bound WillBe, WillBe)" (Artist, dittyofhis own devising, (Gil, BMI),whichsounds tobe theirlatestsmash ASCAP), her way (A p p le "Down to the Valley" (Sun- just right for the summer- (Reprise 0923). 1823). beam, BM!) (RCA 74-0362). time (Epic 5-10629). SLEEPER PICKS OF THE WEEK SORRY SUZANNE (Jan-1111 Auto uary, Embassy BMI) 4526 THE GLASS BOTTLE Booker T. & the M. G.'s do Canned Heat do "Going Up The Glass Bottle,a group JerryBlavat,Philly'sGea something just alittledif- the Country" (Metric, BMI) ofthreeguysandthree for with the Heater,isal- ferent,somethingjust a astheydo itin"Wood- gals, introduce themselves ready clicking with "Tasty littleliltingwith"Some- stock," and it will have in- with "Sorry Suzanne" (Jan- (To Me),"whichgeators thing" (Harrisongs, BMI) creasedmeaningto the uary, BMI), a rouser (Avco andgeatoretteswilllove (Stax 0073). teens (Liberty 56180). Embassy 4526). (Bond 105). ALBUM PICKS OF THE WEEK DianaRosshasherfirst "Johnny Cash the Legend" "The Me Nobody Knows" "The Naked Carmen" isa solo album here, which is tributed in this two -rec- isthe smash off-Broadway "now"-ized versionofBi- startsoutwithherfirst ord set that includes' Fol- musical adaptation of the zet's timeless opera. -

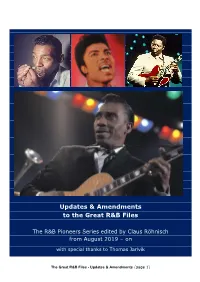

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch from August 2019 – on with special thanks to Thomas Jarlvik The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 1) John Lee Hooker Part II There are 12 books (plus a Part II-book on Hooker) in the R&B Pioneers Series. They are titled The Great R&B Files at http://www.rhythm-and- blues.info/ covering the history of Rhythm & Blues in its classic era (1940s, especially 1950s, and through to the 1960s). I myself have used the ”new covers” shown here for printouts on all volumes. If you prefer prints of the series, you only have to printout once, since the updates, amendments, corrections, and supplementary information, starting from August 2019, are published in this special extra volume, titled ”Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files” (book #13). The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 2) The R&B Pioneer Series / CONTENTS / Updates & Amendments page 01 Top Rhythm & Blues Records – Hits from 30 Classic Years of R&B 6 02 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography 10 02B The World’s Greatest Blues Singer – John Lee Hooker 13 03 Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters 17 04 The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters 18 05 The Blues Giants of the 1950s – Twelve Great Legends 28 06 THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ’50s – Rhythm & Blues Harmony 48 07 Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ’n’ Roll – Idols Making Music History 62 08 Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons 66 09 The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers from the -

Copyright OUTLINE

COPYRIGHT – PROF. REESE, SPRING 2009 • INTRODUCTION o Characteristics . Public goods, nonexcludability and nonrivalrousness . Intangible gooDs o Concerns . Financial benefit (incentives to create) . Attribution . Accuracy . Control . Privacy o ProbleMs . Creates Monopoly . Less access/higher costs • SUBJECT MATTER o Constitutional . Federal, not patchwork of state protections . Restrictions on Congress • Limited time for exclusive rights • Who can get protection • Purpose (science/useful arts) • Subject Matter: writings of authors . Note: just because Constitution perMits Congress to grant copyright protection, it Does not Mean that Congress HAS to o Subject Matter BroaDly DefineD . Author = originator of work . Writing = physical forM expressing iDeas of the MinD . ProMote Progress includes works for coMMercial purpose . Originality: intellectual proDuction, though, or Mental conception, not a qualitative juDgMent of artistic value o Courts on subject Matter: ORIGINALITY . Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony (1884): Oscar WilDe photo • ∂’s challenge: photos are not “authorship” • HolDing: photographs are writings—represent “original intellectual conceptions of the author” o Early Congress protecteD Maps/charts, recreations of the real worlD o Define writings: “all forms by which the ideas in the mind of the author are given visible expression” o Reject categorical exclusion of photos: originality thresholD Met . Goldstein v. California (1973): doesn’t have to be visible • Writings incluDes physical expression of sounDs, any physical rendering . Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographic (1903): circus aDvertiseMents • ∂’s challenge, drawn from life to advertise • HolDing: low threshold of originality o Shows author’s personality, even in unpretentious pictures o ComMercial purpose does not reMove from “useful arts”—value because of consuMer DeManD for copies o Ends lower court trenD aligning copyright with fine arts o Court does not judge artistic quality o Statutory Subject Matter: §102 . -

The Adventure of the Shrinking Public Domain

ROSENBLATT_FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 2/12/2015 1:10 PM THE ADVENTURE OF THE SHRINKING PUBLIC DOMAIN ELIZABETH L. ROSENBLATT* Several scholars have explored the boundaries of intellectual property protection for literary characters. Using as a case study the history of intellectual property treatment of Arthur Conan Doyle’s fictional character Sherlock Holmes, this Article builds on that scholarship, with special attention to characters that appear in multiple works over time, and to the influences of formal and informal law on the entry of literary characters into the public domain. While copyright protects works of authorship only for a limited time, copyright holders have sought to slow the entry of characters into the public domain, relying on trademark law, risk aversion, uncertainty aversion, legal ambiguity, and other formal and informal mechanisms to control the use of such characters long after copyright protection has arguably expired. This raises questions regarding the true boundaries of the public domain and the effects of non-copyright influences in restricting cultural expression. This Article addresses these questions and suggests an examination and reinterpretation of current copyright and trademark doctrine to protect the public domain from formal and informal encroachment. * Associate Professor and Director, Center for Intellectual Property Law, Whittier Law School. The author is Legal Chair of the Organization for Transformative Works, a lifelong Sherlock Holmes enthusiast, and a pro bono consultant on behalf of Leslie Klinger in litigation discussed in this Article. I would like to thank Leslie Klinger, Jonathan Kirsch, Hayley Hughes, Hon. Andrew Peck, and Albert and Julia Rosenblatt for their contributions to the historical research contained in this Article. -

September 06-Final.Indd

2007 International Midwinter Convention 2007 International Buffalo Bills-Era Midwinter Convention Quartet Contest January 21 - 28, 2007 Throughout 2007, we’ll be celebrating the longevity of barbershop music as Headquarters Hotel: Hyatt Regency evidenced by the 50th Anniversary of The Venue: Kiva Auditorium Music Man. As a tribute to this endearing showcase for barbershop music, the 2007 promises to be a banner year for the Barbershop Harmony Society will host the Buffalo Bills-Era Society and you can help launch it in true four-part harmony style. At Quartet Contest. Sing the old songs the way they did fifty years ago. this year’s Midwinter Convention, history and harmony go hand-in- Experience the five-category judging system, and see how your hand. You’ll experience the best from the past, plus encounter some quartet might have done against our most famous champs! All new things to broaden your barbershop horizons. We’ll look back at details regarding the contest, entry form and rules are listed on what has made barbershop music so popular and we’ll look ahead to www.barbershop.org/musicman. Not only will first, second and see where Barbershoppers are taking the music in the future. Here’s third place winners get bragging rights, but they’ll get their share of what’s in store for you. $6,000 in prize money being donated by members of the Pioneers. Time for Tags Midwinter Golf Outing Plenty of time will be set aside between workshops, seminars, Join us for the golf outing on Wednesday, January 24, 2007 at the shows and speakers for getting together with fellow singers. -

EU Harmonisation of the Copyright Originality Criterion (Pdf)

NEWS June 2012 EU harmonisation of the copyright originality criterion As a consequence of a number of copyright rulings from the CJEU, the Swedish threshold of originality requirement is being superseded by an EU originality criterion. In this article, Henrik Bengtsson, IP expert at Delphi in Stockholm, reports on the development and the possible impact on the harmonisation of Swedish copyright law. Less than two years ago, the Swedish Supreme Court rendered its judgment in the Mini Maglite case (NJA 2009 s 159) and ruled that the Mini Maglite flashlight was copyright protected. The Mini Maglite case concerned the pre-requisites under which a work of applied art meets the threshold of originality. The Supreme Court’s view on the threshold of originality concept vis-à-vis “the author’s own intellectual creation” One of the legal issues in the Mini Maglite case was whether the judgment should be based on a Swedish originality requirement or on the EU originality criterion enshrined in the EU copyright directives. The Supreme Court found that the EU harmonisation of copyright law was limited to computer programs, photography and database directives, and was not applicable to industrial designs; “Under two EC directives, computer programs and photographs could be covered by copyright protection, inter alia, on the condition that the work is original in the sense that it is the author’s own intellectual creation; it is added that no other tests shall be applied as regards the right to protection (Directive 91/250/EEC and Directive 93/98/ EEC). A directive regarding legal protection for databases has been drafted in a similar way in this respect (96/9/EC). -

1 Quality, Merit, Aesthetics and Purpose: an Inquiry Into EU

This is a preprint of an article published in the RIDA - Revue Internationale du Droit d’Auteur, no. 236 (April 2013), pp. 100-295, with a full-text translation in French by Margaret PLATT-HOMMEL and in Spanish by Antonio MUÑOZ. Quality, merit, aesthetics and purpose: An inquiry into EU copyright law’s eschewal of other criteria than originality Stef van Gompel & Erlend Lavik* One of the most debated topics in European copyright law today is the harmonization of the concept of originality and the subject-matter of copyright by the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU). Up until the Infopaq I decision of 2009, in which it ruled that copyright subsists in subject-matter ‘which is original in the sense that it is its author’s own intellectual creation’,1 computer programs, photographs and databases were the only three types of works for which the originality test was explicitly harmonized at the EU level.2 Beyond these cases, it was thought that ‘Member States remain free to determine what level of originality a work must possess for granting it copyright protection’.3 The CJEU nonetheless extended the application of the criterion of the author’s own intellectual creation to other types of works, including newspaper articles (Infopaq I); graphic user interfaces of computer programs (BSA); (unregistered) industrial design (Flos); works exploited within the framework of television broadcasts, such as opening video sequences, anthems, pre-recorded films and graphics (Football Association Premier League); and programming languages and the format of data * Stef van Gompel is post-doc researcher at the Institute for Information Law (IViR) of the University of Amsterdam; Erlend Lavik is post-doc researcher at the Department of Information Science and Media Studies (Infomedia) of the University of Bergen. -

John Coltrane Black Pearls Mp3, Flac, Wma

John Coltrane Black Pearls mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Black Pearls Country: US Style: Hard Bop, Post Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1737 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1797 mb WMA version RAR size: 1227 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 154 Other Formats: APE VQF ADX AAC ASF MP1 MP3 Tracklist Hide Credits Black Pearls A1 13:05 Written-By – Billy Graham* Lover Come Back To Me A2 7:25 Written-By – Hammerstein*, Romberg* Sweet Sapphire Blues B 18:20 Written-By – R. Weinstock* Companies, etc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey Credits Bass – Paul Chambers Drums – Art Taylor Liner Notes [Apr. 1964] – Michael Gold Piano – Red Garland Recorded By – Rudy Van Gelder Supervised By [Supervision] – Bob Weinstock Tenor Saxophone – John Coltrane Trumpet – Donald Byrd Notes Blue center labels with trident on right. Jacket manufactured without "Stereo" printed on front cover; instead has a "Stereo" sticker. Recorded in Hackensack, NJ, May 23, 1958. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side A runout): STEREO PRST·7316·A· VAN GELDER Matrix / Runout (Side B runout): STEREO PRST·7316·B· VAN GELDER Other versions Title Category Artist Label Category Country Year (Format) PR 7316, PRST John Black Pearls Prestige, PR 7316, PRST US 1964 7316 Coltrane (LP, Album) Prestige 7316 Black Pearls Prestige, PR 7316, P-7316, John PR 7316, P-7316, (LP, Album, Prestige, Germany Unknown OJC-352 Coltrane OJC-352 RE) Prestige Black Pearls John DOL729 (LP, Album, DOL DOL729 Europe 2013 Coltrane RE, 140) Prestige, Black Pearls Original -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron.