Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamble-Le-Rice VILLAGE MAGAZINE JULY 2018

Hamble-le-Rice VILLAGE MAGAZINE JULY 2018 Hamble River Raid, see page 7 School holidays will soon be here! Issue 317 Published by Hamble-le-Rice Parish Council and distributed free throughout the Parish and at www.hambleparishcouncil.gov.uk Hamble marquee hire Marquee hire, all types of catering, temporary bars, furniture hire and luxury toilets for Weddings, parties, corporate events and all occasions. www.rumshack.co.uk rumshack Call us on 07973719622 for information EVENT MANAGEMENT email enquires to [email protected] 1 WOULD YOU LIKE TO... • support the community? • gain work experience? • meet new people? • learn new skills? You can achieve all this and more as a volunteer at The Mercury Community Hub WE’RE RECRUITING NOW FOR THE SEPTEMBER OPENING 023 8045 3422 the mercury [email protected] you make the di erence 2 3 St Andrew’s Church Message from the Clerk HambleleRice Popping down to the Foreshore and they start any extraction. With this in mind, Westfi eld Common at lunchtime for a quick it is unlikely that they would be on site 7th July 2018 bite to eat I am always surprised at how before 2020 although these indications are lovely and unique Hamble is. There can be only indicative. 12 Noon until 4pm few places that can beat Hamble with its Cemex believe that there is approximately Entertainment waterfront offering, the great range of places 1.6 million tonnes of gravel on the Airfi eld Dog Show to spend leisure time and opportunities for Great Hamble Bake Off and expect to extract it over a 7-8 year work. -

Westenderwestender

NEWSLETTER of the WEST END LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY WESTENDERWESTENDER NOVEMBER—DECEMBER 2012 CHRISTMAS EDITION ( PUBLISHED SINCE 1999 ) VOLUME 8 NUMBER 8 TUDOR REVELS IN SOUTHAMPTON CHAIRMAN Neville Dickinson VICE-CHAIRMAN Bill White SECRETARY Lin Dowdell MINUTES SECRETARY Vera Dickinson TREASURER Peter Wallace MUSEUM CURATOR Nigel Wood PUBLICITY Ray Upson MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Delphine Kinley RESEARCHER Pauline Berry WELHS... preserving our past for your future…. VISIT OUR WEBSITE! Website: www.westendlhs.hampshire.org.uk E-mail address: [email protected] West End Local History Society is sponsored by West End Local History Society & Westender is sponsored by EDITOR Nigel.G.Wood EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION ADDRESS WEST END 40 Hatch Mead West End PARISH Southampton, Hants SO30 3NE COUNCIL Telephone: 023 8047 1886 E-mail: [email protected] WESTENDER - PAGE 2 - VOL 8 NO 8 GROWING UP IN WEST END DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By Ray Upson I was at the tender age of 3 years old when the Second World War broke out. A little young to fully understand what was going on – I soon learnt! We were living in the white cottage just up from what is now Rostron Close in Chalk Hill. In those days it was attached to the Scaffolding (Great Britain) depot and an aunt and uncle lived next door and shared our pantry as a makeshift air raid shelter. This room had a door leading into the back yard. My first vivid memory was (I think) during the Blitz on Southampton. The most frightening incident was my father and uncle holding onto the door which was shaking from the blast of bombs. -

St John Archive First World War Holdings

St John Archive First World War Holdings Reference Number Extent Title Date OSJ/1 752 files First World War 1914-1981 Auxiliary Hospitals in England, Wales and OSJ/1/1 425 files Ireland during the First World War 1914-1919 OSJ/1/1/1 1 file Hospitals in Bedfordshire 1917 OSJ/1/1/1/1 1 file Hinwick House Hospital, Hinwick, Bedfordshire. 1917 OSJ/1/1/2 3 files Hospitals in Berkshire 1915-1918 General correspondence about auxiliary OSJ/1/1/2/1 1 file hospitals in Berkshire. c 1918 Park House Auxiliary St John's Hospital, OSJ/1/1/2/2 1 file Newbury, Berkshire 1917-1918 Littlewick Green Hospital and Convalescent OSJ/1/1/2/3 1 file Home, Berkshire 1915 OSJ/1/1/3 7 files Hospitals in Buckinghamshire 1914-1918 General correspondence about auxiliary OSJ/1/1/3/1 1 file hospitals in Buckinghamshire 1916-1918 Auxiliary Hospital, Newport Pagnell, OSJ/1/1/3/2 1 file Buckinghamshire 1917 OSJ/1/1/3/3 1 file The Cedars, Denham, Buckinghamshire 1915 Chalfont and Gerrard's Cross Hospital, Chalfont OSJ/1/1/3/4 1 file St Peters, Buckinghamshire 1914 OSJ/1/1/3/5 1 file Langley Park, Slough, Buckinghamshire 1914-1915 Tyreingham House, Newport Pagnell, OSJ/1/1/3/6 1 file Buckinghamshire 1915 OSJ/1/1/3/7 1 file Winslow VAD Hospital, Buckinghamshire 1917 OSJ/1/1/4 1 file Hospitals in Cambridgeshire 1915 Report of Red Cross VAD Auxiliary Hospitals, OSJ/1/1/4/1 1 file Cambs 1915 OSJ/1/1/5 1 file Hospitals in Carmarthenshire 1917-1918 OSJ/1/1/5/1 1 file Stebonheath Schools, Llanelly, Carmarthenshire 1917-1918 OSJ/1/1/6 9 files Hospitals in Cheshire 1914-1918 General correspondence about auxiliary OSJ/1/1/6/1 1 file hospitals in Cheshire 1916-1918 OSJ/1/1/6/2 1 file Bedford Street School, Crewe 1914 OSJ/1/1/6/3 1 file Alderley Hall Hospital, Congleton, Cheshire 1917 OSJ/1/1/6/4 1 file St. -

Other Material

HAMPSHIRE FIELD CLUB, 1891. Established 1885, for the study of the Natural History and Antiquities of the County. $rt0tbent. W. E. DARWIN, J.P., B.A., F.G.S. $a*t;fre*ibtnt. .W. WHITAKER, B.A., F.R.S., F.G.S. 19tces$lre0tuent*. THE VERY REV. THE DEAN OF PROFESSOR J, L. NOTTER, M.D WINCHESTER P. L. SCLATER, M.A., Ph. D., REV. W. L. W. EYRE F.R.S., F.L.S. $jon. Smjfttrer. MORRIS MILES. Committee. ANDREWS, DR. GRIFFITH, C., M.A. BUCKELL, DR. E. ' HERVEY, REV. A. C. CLUTTERBUCK, REV. R. H. PINDER, R. G., F.R.I.B.A. COLENUTT, G. W. PEAKE, J. M. CROWLEY, F. SHORE, T. W., F.G.S., F.C.S. DALE, W., F.G.S. THOMAS, J. BLOUNT, J.P. EYRE, REV. W. L. W. VAUGHAN, REV. J., M.A. GODWIN, REV. G. N., B.D., B.A. WARNER, F. J., FX.S. MINNS, REV. G. W., LL.B., Editor. fjon. j&ecretarieji. General Secretary—W'. DALE, F.G.S., 5, Sussex Place, Southampton Financial Secretary—]. BLOUNT THOMAS, J.P., 179, High Street, Southampton Organizing Secretary—T. W. SHORE, F.G.S., F.C.S., Overstrand, Woolston,. Southampton %ocd Secretaries!. Alton—REV. A. C. HERVEY Isle of Wight—G. W. COLENUTT A Ires/ord—REV. W. L. W. EYRE New Forest—REV. G. N. GODWIN Andover—REV. R. H. CLUTTERBUCK Petersfield—J. M. PEAKE Bournemouth—R.G.PINDER.F.R.I.B.A Romsey—DR. E. BUCKELL Basingstoke—DR. ANDREWS Winchester—-F. J. WARNER, F.L.S. -

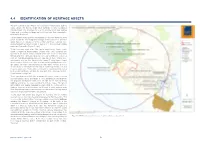

4.4 Identification of Heritage Assets

4.4 IDENTIFICATION OF HERITAGE ASSETS The Site (outlined in red in Figure 91) contains one listed building, Sydney Lodge (Grade II*) but no locally listed buildings or other designated heritage assets. The Site does not lie within a conservation area. Sydney Lodge and its curtilage buildings and structures have been assessed in detail within Section 4.1. For the purpose of this Baseline Assessment a 1 kilometre buffer has been drawn around the Site. Designated heritage assets within the 1 kilometre radius have been considered in this section and those requiring more detailed assessment taken forward in Section 4.3. The identified heritage assets are illustrated in Figure 91 (right). To the immediate north of the Site, just beyond College Copse, is the Grade II registered Royal Victoria Country Park. This comprises the grounds of the former military hospital within the extent of associated Ministry of Defence land ownership and covers 44 ha. Within the registered Park are four listed buildings, however, only one of these shares some inter-visibility with the Site, this being the Grade II* listed former Chapel which is now a visitor’s centre. Due to a lack of inter-visibility between the Site and the other three listed buildings, the latter will be considered merely in the context of the Registered Park and its overall significance. The Site constitutes part of the Park’s wider setting and the contribution this makes to its overall significance will form the main part of the assessment of the Royal Victoria Country Park. To the immediate west of the Site is Hamblecliffe House, Grade II, and its associated Stable Block, also Grade II. -

WESTENDER MAY-JUNE 2016.Pub

NEWSLETTER of the WEST END LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY WESENDERWESENDERWESTENDER GREAT WAR 100 WESTENDER GREAT WAR 100 MAY - JUNE 2016 ( PUBLISHED CONTINUOUSLY SINCE 1999 ) VOLUME 10 NUMBER 5 CHAIRMAN WEST END’S FIRE FIGHTERS Neville Dickinson AT NETLEY HOSPITAL VICE-CHAIRMAN Bill White SECRETARY Lin Dowdell MINUTES SECRETARY Vera Dickinson TREASURER & WEBMASTER Peter Wallace MUSEUM CURATOR Nigel Wood PUBLICITY Ray Upson MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Delphine Kinley RESEARCHERS Pauline Berry Paula Downer WELHS... preserving our past for your future…. Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley on fire in 1956 and Westends Water-tender in VISIT OUR the centre of the picture with its rear end facing camera registration number 762AHO. WEBSITE! As published in ‘Stop Message’, the magazine of Hampshire Fire & Rescue Website: Service Past Members Association. www.westendlhs.co.uk Photo forwarded to us by WELHS member Colin Mockett who was a fire fighter based at West End Fire Station. E-mail address: [email protected] West End WestLocal End History Local HistorySociety Society & Westender is sponsored is spons by ored by EDITOR Nigel.G.Wood EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION ADDRESS WEST END 40 Hatch Mead West End PARISH Southampton, Hants SO30 3NE Telephone: 023 8047 1886 COUNCIL E-mail: [email protected] WESTENDER - PAGE 2 - VOL 10 NO 5 MEMORIES OF MOORHILL, THORNHILL AND WEST END 1949 - 1958 (Part 2) By Bruce Bagley I come now to Bungalow Town and Donkey Common. We too played on the swinging tree. At the watery site of the former Thornhill Park House we caught fantail and common newts. One day, my brother was down a brick culvert when from above I saw an adder slither out of a horizontal pipe. -

0042 WESTENDER MARCH-APRIL 2006.Pdf

NEWSLETTER of the WEST END LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY WESTENDERWESTENDER MARCH—APRIL 2006 THE TENTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE SOCIETY VOLUME 5 NUMBER 4 CHAIRMAN LOCAL LEGENDS (3) Neville Dickinson BRIGADIER GENERAL SIR G.H. GATER VICE-CHAIRMAN Bill White SECRETARY Pauline Berry MINUTES SECRETARY Rose Voller TREASURER Peter Wallace MUSEUM CURATOR Nigel Wood PUBLICITY Ray Upson MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Delphine Kinley Son of W.H.Gater of Winslowe House, West End, George Henry Gater was born in 1886 and educated at Winchester and New College Oxford. He enlisted in the Sherwood Foresters at the outbreak of war and served at Gallipoli with their 9th Battalion. In that campaign he was VISIT OUR promoted to Major and later awarded a DSO in March 1916. He went with his battalion to France in 1916 and served on the Somme, appointed to command 6th Btn. Lincolnshire Regt. as WEBSITE! Lt. Colonel during which he was awarded a bar to his DSO. A General who led from the front it was whilst in France he was severely wounded in the face. In November 1917 he was promoted Website: to Brigadier General in command of 62nd Brigade. A General at the age of 31, one of the www.hants.org.uk/westendlhs/ youngest in the British Army having served only 3 years in the army! In 1918 he was again wounded during the last big German Offensive whilst commanding a scratch unit to stem the German tide. He was made a Commander of the Legion of Honour and awarded the Croix de E-mail address: Guerre as well as his DSO and bar and was mentioned in despatches four times, he was [email protected] apparently next in line to command a Division when Peace was proclaimed. -

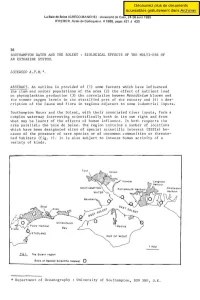

Southampton Water and the Solent : Biological Effects of the Multi-Use of an Estuarine System

La Baie de Seine (GRECO-MANCHE) - Université de Caen, 24-26 avril 1985 IFREMER. Actes de Colloques n. 4 1986, pages 421 à 430 36 SOUTHAMPTON WATER AND THE SOLENT : BIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF THE MULTI-USE OF AN ESTUARINE SYSTEM. LOCKWOOD A.P.M.*. ABSTRACT. An outline is provided of (1) some factors which have influenced the clam and oyster populations of the area (2) the effect of nutrient load on phytoplankton production (3) the correlation beween Mesodinium blooms and the summer oxygen levels in the stratified part of the estuary and (4) a des cription of the fauna and flora in regions adjacent to some industrial inputs. Southampton Water and the Solent, with their associated river inputs, form a complex waterway interesting scientifically both in its own right and from what may be learnt of the effects of human influence. In both respects the area parallels the baie de Seine. The region contains a number of locations which have been designated sites of special scientific interest (SSSIs) be cause of the presence of rare species or of uncommon communities or threate ned habitats (fig. 1). It is also subject to intense human activity of a variety of kinds. Department of Oceanography : University of Southampton, S09 5NH, U.K. 422 Principal amongst these are : 1) civic and domestic inputs via a number of sewage outlets, 2) industrial effluents, particularly along the western shore of Southampton Water, 3) river inputs with their associated nutrient load from agricultural land, trout farm etc.. , 4) dredging for gravel and the maintenance of shipping lanes, 5) sport sailing, and 6) commercial fishing for Oysters (Ostrea edulis), American Clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) and Bass (Dicentrachus lahrax) together with semi-commercial or sport fishing for Cod (Gadus morhua), Mackerel (Scomber scomber) Plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) and other species. -

Private Ernest Gough Coxon Royal Army Medical Corps

In memory of Private Ernest Gough Coxon Royal Army Medical Corps Regimental Number 101620 Ernest Gough Coxon was born in Netherseal in April 1890, son of William Brotherhood Coxon and Elizabeth (nee Gough). He was baptised on 29th March 1891. Ernest was the third of four children. He had two brothers, John William and Edward, and a sister, Mary Elizabeth. In the 1891 Census records, Ernest and his family were living at the Cricketts Inn, Acresford. His grandfather John Brotherhood was a Licensed Victualler and his father was a Brewery Labourer. His mother Elizabeth was the Housekeeper. 1 1 1 Page Family Tree information provided by Jill Hempsall using records from Ancestry.co.uk The 1891 Census shows Ernest’s father William was recorded with a surname of Brotherhood, as is the whole family. This seems to be something that changes for each Census. Sometimes the family are registered as Coxon (1861, 1901 and 1911), and sometimes Brotherhood (1871, 1881).2 Ernest’s grandfather is a Brotherhood. 2 2 Page www.ancestry.co.uk 1891 Census At the time of the 1891 Census, there were five cottages around the Cricketts Inn, with families living in each one. The occupations listed were Maltster, Brewery Waggoner, Coachman, and Farm Labourer/Shepherd.3 In the 1901 Census, Ernest was 11 years old and still living at the Cricketts Inn with his family and grandfather. Ernest’s father was a Farm Labourer Waggoner and his mother a Dairy Maid. Ernest’s eldest brother John was a Farm Labourer Cowman.4 By 1911, Ernest was 21 years old, single and still living with his family. -

Exploring the Netley British Red Cross Magazine: an Example of the Development of Nursing and Patient Care During the First World War

Received: 21 September 2019 | Revised: 7 October 2020 | Accepted: 10 October 2020 DOI: 10.1111/nin.12392 FEATURE Exploring The Netley British Red Cross Magazine: An example of the development of nursing and patient care during the First World War Nestor Serrano-Fuentes1,2 | Elena Andina-Diaz2,3,4 1School of Health Sciences, NIHR ARC Wessex, University of Southampton, Abstract Southampton, UK Netley Hospital played a crucial role in caring for the wounded during the nineteenth 2 SALBIS Research Group, University of century and twentieth century, becoming one of the busiest military hospitals of the Leon, Leon, Spain 3Nursing and Physiotherapy Department, time. Simultaneously, Florence Nightingale delved into the concept of health and de- Faculty of Health Sciences, University of veloped the theoretical basis of nursing. This research aims to describe the experi- Leon, Leon, Spain ences related to nursing and patient care described in The Netley British Red Cross 4EYCC Research Group, University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain Magazine during the First World War. The analysis displays different nurses' roles and the influence of environmental factors in the delivery of the soldiers' care. There are Correspondence Nestor Serrano-Fuentes, School of Health indications that Nightingale's ideas would have infiltrated the nursing practices and Sciences, University of Southampton, other aspects of the soldiers' recovery at Netley. The history of the Netley Red Cross Building 67, University Road, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK. Hospital shows the theoretical and practical advancement of nursing care towards a Email: [email protected] holistic approach. KEYWORDS First World War, Florence Nightingale, Nursing History, qualitative research, Red Cross 1 | INTRODUCTION The Royal Victoria Hospital or Netley Hospital was the largest British military hospital built after the Crimean War and a site of Nursing during conflict is an important phenomenon that has importance to nursing. -

Hospital Planning

HOSPITAL PLANNING: REVISED THOUGHTS ON THE ORIGIN OF THE PAVILION PRINCIPLE IN ENGLAND by ANTHONY KING OF the many domestic reforms hastened by the Crimean War, the rethinking of hospital design was one which most concerned the mid-Victorian architect. The deplorable state of military hospitals revealed by the Report of the Commission appointed to inquire into the Regulations affecting the Sanitary Condition of the Army, the Organization of Military Hospitals and the Treatment of the Sick and Wounded, 1858,1 stimulated the discussion of civil hospital reform2 which was already active in the mid-1850s. The change which took place from the early to the late nineteenth century, from conditions 'where cross-infection was a constant menace' to those 'where hospitals [were] ofpositive benefit to a substantial number ofpatients'3 occurred largely in the years following this report; improved medical knowledge, nursing reforms, increased attention to sanitation, and better planning and administra- tion, combined to ensure that Florence Nightingale's maxim-'The first requirement in a hospital is that it should do the sick no harm'4-was far less relevant in 1890 than it had been fifty years before. Prior to 1861, there had been a considerable variety of different architectural designs for hospitals in this country, 'but in the 1870s and 1880s, the vast majority of new hospitals and rebuilt hospitals conformed to one basic plan-a series of separate pavilions placed parallel to one another'.5 The 'pavilion system', as conceived by its advocates, consisted preferably of single storey, or failing this, two-storey ward blocks, usually placed at right angles to a linking corridor which might either be straight or enclosing a large central square; the pavilions were widely separated, usually by lawns or gardens. -

The Ancient Parish of Hound

356 THE ANCIENT PARISH OF HOUND. [From the Hampshire Observer^ The northern part of this parish was formerly covered with heaths, which formed its extensive commons. This land had much the same character as Beaulieu Heath on the opposite side of Southampton Water. Plateau gravel, which has been quarried from time immemorial, lies upon its higher parts, as it does on Beaulieu Heath, and formerly, I have no doubt, the land had upon it many barrows tumuli thrown up as funeral monuments to important people of the Celtic race, such as . still remain on Beaulieu Heath. A tumulus still exists near Netley Hill, where there are traces of others. From a similar tumulus near the border of the parish at West End, an urn was taken,' containing the cremated remains of some chieftain of the Bronze Age,, and this is now preserved in the Hartley Museum. There is some evidence to show that the Celtic inhabitants of this part of Hampshire occupied the peninsular knolls between the little creeks on both sides of Southampton Water as dwelling sites. Such positions would doubtless have afforded them facilities for obtaining fish as a food supply and have been good defensive sites. The discovery of Romano- British pottery on such a knoll, where the Superintendent's house of the Royal Military Asylum at Netley now stands, shows that Hound had its inhabitants long before the time of the Saxon Conquest.. That the Romans occupied part of it is proved by their remains which have been discovered. When the Military Asylum, attached to Netley Hospital, was built, in 1867, in addition to the Romano-British pottery I have mentioned, a considerable number of Roman coins were found.