Language: a Reaction to the Dematerialization of Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue 8 – ( June 2017 )

Catalogue 8 – ( June 2017 ) 1. Carl ANDRE. Carl Andre. Works in Belgium. Ghent. Imschoot, Uitgevers. 1993. (22 x 15.5 cm). pp. 56. With 26 black-and-white illustrations. Publisher’s cloth, with dust-jacket. Carl Andre's introduction reads: "This book contains an excellent sampling of my work in Belgium. It is by no means a complete list of works created or exhibited by me in Belgium or presently in Belgian collections. I have said that the New York art audience is the worst in the world. The Flemish art audience is one of the very best!”. One of the 65 deluxe hardback copies, (this one of 25 examples numbered with Roman numerals), signed by Carl Andre in pencil under his printed introduction. $ 750 2. Giovanni ANSELMO. Lire. Ghent. Imschoot, Uitgevers. 1990. (22 x 15.5 cm). pp. (80). Publisher’s cloth, with dust-jacket. Artist’s book, printed along the same lines as Anselmo’s legendary 1972 book Leggere. The single word ‘Lire’ gradually reduces in size, page after page, until it is almost unreadable. Then it comes back gradually, until the word fills the complete field of vision of the book, the pages go completely black, and the word becomes invisible. Published at the occasion of the exhibition-series "Affinités Sélectives" at the Paleis voor Schone Kunsten, Brussels, Belgium, organized by Bernard Marcadé. This is one of 25 deluxe hardback copies, numbered and signed in pencil by Anselmo. $ 1200 3. Hans ARP & Sophie TAEUBER-ARP. Hans Arp. Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Hannover. Kestner-Gesellschaft. 1955. (21 x 15 cm). -

Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979

Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Dennis, M. Submitted version deposited in Coventry University’s Institutional Repository Original citation: Dennis, M. () Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979. Unpublished MSC by Research Thesis. Coventry: Coventry University Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Some materials have been removed from this thesis due to Third Party Copyright. Pages where material has been removed are clearly marked in the electronic version. The unabridged version of the thesis can be viewed at the Lanchester Library, Coventry University. Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Mark Dennis A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy/Master of Research September 2016 Library Declaration and Deposit Agreement Title: Forename: Family Name: Mark Dennis Student ID: Faculty: Award: 4744519 Arts & Humanities PhD Thesis Title: Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Freedom of Information: Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) ensures access to any information held by Coventry University, including theses, unless an exception or exceptional circumstances apply. In the interest of scholarship, theses of the University are normally made freely available online in the Institutions Repository, immediately on deposit. -

I Is for 3 6 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 Institute Local

I is for Institute Local Context 2/22, 6:30 PM 3 Asian Arts Initiative 6 The Fabric Workshop and Museum 9 Fleisher Art Memorial 11 FJORD Gallery 13 Marginal Utility 15 Mural Arts Philadelphia 17 Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) 19 Philadelphia Contemporary 21 Philadelphia Museum of Art 24 Philadelphia Photo Arts Center (PPAC) 26 The Print Center 28 Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, The University of the Arts 30 Temple Contemporary 32 The Village of Arts and Humanities 34 Ulises 36 Vox Populi What’s in a name? This is the question underlying our year-long investigation into ICA: how it came to be, what it means now, and how we might imagine it in the future. ASIAN ARTS INITIATIVE Address 1219 Vine Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 Website asianartsinitiative.org Founding Date Spring, 1993 Staff Size 7 Full-time, 7 Part-time. Do you have a physical location? Yes Do you have a collection? No Logo Mission Statement A meeting place, an idea lab, a support system, and an engine for positive change, Asian Arts Initiative strives to empower communities through the richness of art. We believe in a universal human capacity for creativity, and we support local art and artists as a means of interpreting, sharing, and shaping contemporary cultural identity. Created in 1993 in response to community concerns about rising racial tension, we serve a diverse constituency of both youth and adults—Asian immigrants, Asian Americans born in the U.S., and non-Asians—who come together to give voice to experiences of cultural identity and heritage and claim the power of art- making as a vital form of expression and catalyst for social change. -

Mapping the Landscape of Socially Engaged Artistic Practice

Mapping the Landscape of Socially Engaged Artistic Practice Alexis Frasz & Holly Sidford Helicon Collaborative artmakingchange.org 1 “Artists are the real architects of change, not the political legislators who implement change after the fact.” William S. Burroughs 2 table of contents 4 28 purpose of the research snapshots of socially engaged art making Rick Lowe, Project Row Houses | Laurie Jo Reynolds, Tamms Year Ten | Mondo Bizarro + Art Spot Productions, 9 Cry You One | Hank Willis Thomas | Alaskan Native methodology Heritage Center | Queens Museum and Los Angeles Poverty Department | Tibetan Freedom Concerts | Alicia Grullón | Youth Speaks, The Bigger Picture 11 findings Defining “Socially Engaged Art” | Nine Variations 39 in Practice | Fundamental Components (Intentions, supporting a dynamic ecosystem Skills, and Ethics) | Training | Quality of Practice 44 resources acknowledgements people interviewed or consulted | training programs | impact | general resources | about helicon | acknowledgments | photo credits purpose of the research Helicon Collaborative, supported by the Robert Raus- tural practices of disenfranchised communities, such chenberg Foundation, began this research in 2015 in as the African-American Mardi Gras Indian tradition order to contribute to the ongoing conversation on of celebration and protest in New Orleans. Finally, we “socially engaged art.” Our goal was to make this included artists that are practicing in the traditions important realm of artmaking more visible and legible of politically-inspired art movements, such as the to both practitioners and funders in order to enhance Chicano Arts Movement and the settlement house effective practice and expand resources to support it. movement, whose origins were embedded in creat- ing social change for poor or marginalized people. -

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 Art & Language Large Print Guide

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 12 April – 29 August 2016 Art & Language Large Print Guide Please return to exhibition entrance Art & Language 1 To focus on reading rather than looking marked a huge shift for art. Language was to be used as art to question art. It would provide a scientific and critical device to address what was wrong with modernist abstract painting, and this approach became the basis for the activity of the Art & Language group, active from about 1967. They investigated how and under what conditions the naming of art takes place, and suggested that meaning in art might lie not with the material object itself, but with the theoretical argument underpinning it. By 1969 the group that constituted Art & Language started to grow. They published a magazine Art-Language and their practice became increasingly rooted in group discussions like those that took place on their art theory course at Coventry College of Art. Theorising here was not subsidiary to art or an art object but the primary activity for these artists. 2 Wall labels Clockwise from right of wall text Art & Language (Mel Ramsden born 1944) Secret Painting 1967–8 Two parts, acrylic paint on canvas and framed Photostat text Mel Ramsden first made contact with Art & Language in 1969. He and Ian Burn were then published in the second and third issues of Art-Language. The practice he had evolved, primarily with Ian Burn, in London and then after 1967 in New York was similar to the critical position regarding modernism that Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin were exploring. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

The Contemporary Significance of Design in Art

THE CONTEMPORARY SIGNIFICANCE OF DESIGN IN ART by ARNO MORLAND submitted to PROF. KAREL NEL in January 2005 in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree MA (FA) by Coursework in the Department of Fine Art University of the Witwatersrand School of the Arts Table of Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………..……….…p.1 2. The conceptual climate of contemporary art production………….……….…p.5 3. The social context of contemporary art production……………….………….p.12 4. The adoption of design as creative idiom in contemporary art….……………p.18 5. The artist as designer…………………………………….……………………p.21 6. Conclusion………………………………………………….…………………p.27 7. Bibliography……………………………………………….………………….p.30 8. Illustrations……………………………………………………………………p.32 THE CONTEMPORARY SIGNIFICANCE OF DESIGN IN ART By Arno Morland 1. Introduction Do we live by design? Certainly many of us will live out the majority of our lives in environments that are almost entirely ‘human-made’. If the apparent orderly functionality of nature is likely to remain, for the time being, philosophically controversial, the origin of our human-made environment in design is surely beyond dispute. If this is indeed the case, then the claim by Dianne Pilgrim, director of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, that “design affects our lives every second of the day”, may not be as immodest as it appears to be at first (2000: 06). Perhaps then, it is with some justification that eminent art critic Hal Foster refers to the notion of “total design” to describe what he sees as contemporary culture’s state of comprehensive investment in design (2002: 14). For Foster, we live in a time of “blurred disciplines, of objects treated as mini-subjects”, a time when “everything…seems to be regarded as so much design” (2002: 17). -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 26, 2021 CONTACT: Mayor's Press

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 26, 2021 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] MAYOR LIGHTFOOT ANNOUNCES SHOWTIME® IS DONATING $500,000 FOR SOUTH AND WEST SIDE NEIGHBORHOOD BEAUTIFICATION AND ARTS PROJECTS Donation to Greencorps Chicago green job training program and Chicago Public Art Group focuses on Chicago neighborhoods where the network’s critically acclaimed drama series “The Chi” is filmed CHICAGO – Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot joined Puja Vohra, Executive Vice President of Marketing and Strategy for SHOWTIME, and cast members from its Chicago-based hit show “The Chi,” along with community leaders, today to announce a $500,000 donation from the network to the City’s Greencorps Chicago green job training program and the Chicago Public Art Group. The funding will support and invest in the City’s South and West sides, which have served as key locations for the SHOWTIME drama series “The Chi,” created by Lena Waithe, for four seasons. The grant will pay for the clean-up and beautification of 32 empty lots and six accompanying art installations in Bronzeville and North Lawndale, areas that are part of Mayor Lightfoot’s INVEST South/West initiative that is designed to revitalize community areas in Chicago that have suffered from a legacy of under-investment. "From vibrantly depicting our city's neighborhoods on 'The Chi' to now investing in our city's sustainability, employment and art initiatives, SHOWTIME has demonstrated its commitment to supporting and uplifting our residents," said Mayor Lightfoot. "This donation will make a real difference in our communities and strengthen two of our greatest community-based programs, which are doing incredible work to improve Chicago. -

Oral History Interview with Peter Goulds, 2008 Mar.24-July 28

Oral history interview with Peter Goulds, 2008 Mar.24-July 28 Funding for this interview was provided by the Art Dealers Association of America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Peter Goulds on 2008 March 24 and July 28. The interview took place in Venice CA at the L.A. Louver Gallery, and was conducted by Susan Ford Morgan for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Peter Goulds has reviewed the transcript. His corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview SUSAN FORD MORGAN: So, this is for the Archives of American Art— PETER GOULDS: Okay. SUSAN FORD MORGAN: —for their oral history project, and so, I have to open up my identifying statement, which is: This is Susan Morgan interviewing Peter Goulds at the L.A. Louver Gallery in Venice, California, on, I believe, the— PETER GOULDS: It is Monday, March the 24th— SUSAN FORD MORGAN: —March the 24th— PETER GOULDS: —2008. SUSAN FORD MORGAN: —2008, and this is disk one. And because this is an oral history project we start at the very beginning. -

Future Forward Seattle Waterfront Pier 62 Call for Artists

Future Forward Seattle Waterfront Pier 62 Call for Artists 08/13/2020 Introduction Seattle’s future Waterfront Park is more than a park — it is a once-in-a-generation opportunity where the community’s values, vision, and investments align to achieve lasting economic, social, and environmental value — now, and for the benefit of future generations. This monumental opportunity has led to development of an Artist-In-Residence program that brings new energy and vision to creating a “waterfront for all.” Takiyah Ward was recently named the Future Forward Virtual Artist In Residence by Friends. Leading the artistic vision, Takiyah designed the framework for engaging artists in a range of opportunities to activate the Seattle waterfront. This framework focuses on creative projects that invite exploration of stories and experiences focused on insights of the past, engagement with the present, and vision for the future — PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE. In this context, three distinct projects will be implemented with activities, activations, and installations to illuminate each theme. The current call for artists is for Pier 62 and seeks an artist collective (a group of two or more artists) to explore the theme of PRESENT through the creation of a temporary light sculpture and up to 40 lanterns or luminaries. DETAILS OF THE ARTIST CALL Location: Pier 62 Theme: PRESENT - How do we honor our elders, determine our self, and protect our youth? Artist In Residence Vision Statement “Using varying scales and quantity, Pier 62 will be the canvas for embodying the ideas of artists speaking to present circumstances in relation to elders and youth. -

Ephemera Labels WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 1 EXTENDED LABELS

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 Ephemera Labels WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 1 EXTENDED LABELS Larry Neal (Born 1937 in Atlanta; died 1981 in Hamilton, New York) “Any Day Now: Black Art and Black Liberation,” Ebony, August 1969 Jet, January 28, 1971 Printed magazines Collection of David Lusenhop During the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, publications marketed toward black audiences chronicled social, cultural, and political developments, covering issues of particular concern to their readership in depth. The activities and development of the Black Arts Movement can be traced through articles in Ebony, Black World, and Jet, among other publications; in them, artists documented the histories of their collectives and focused on the purposes and significance of art made by and for people of color. WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 2 EXTENDED LABELS Weusi Group Portrait, early 1970s Photographic print Collection of Ronald Pyatt and Shelley Inniss This portrait of the Weusi collective was taken during the years in which Kay Brown was the sole female member. She is seated on the right in the middle row. WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 3 EXTENDED LABELS First Group Showing: Works in Black and White, 1963 Printed book Collection of Emma Amos Jeanne Siegel (Born 1929 in United States; died 2013 in New York) “Why Spiral?,” Art News, September 1966 Facsimile of printed magazine Brooklyn Museum Library Spiral’s name, suggested by painter Hale Woodruff, referred to “a particular kind of spiral, the Archimedean one, because, from a starting point, it moves outward embracing all directions yet constantly upward.” Diverse in age, artistic styles, and interests, the artists in the group rarely agreed; they clashed on whether a black artist should be obliged to create political art. -

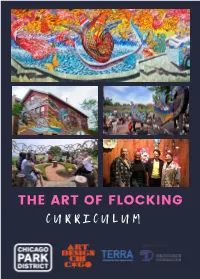

THE ART of FLOCKING CURRICULUM the Art of Flocking Curriculum

THE ART OF FLOCKING CURRICULUM The Art of Flocking Curriculum “There is an art to flocking: staying close enough not to crowd each other, aligned enough to maintain a shared direction, and cohesive enough to always move towards each other.” - adrienne maree brown The Art of Flocking: Cultural Stewardship in the Parks is a celebration of Chicago’s community-based art practices co-facilitated by the Chicago Park District and the Terra Foundation for American Art. A proud member of Art Design Chicago, this initiative aims to uplift Chicago artists with deep commitments to social justice, cultural preservation, community solidarity, and structural transformation. Throughout the summer of 2018, The Art of Flocking engaged 2,500 youth and families through 215 public programs and community exhibitions exploring the histories and legacies of Mexican-American public artist Hector Duarte and Sapphire and Crystals, Chicago's first and longest-standing Black women's artist collective.The Art of Flocking featured two beloved Chicago Park District programs: ArtSeed, designed to engage children ages 3 and up as well as their families and caretakers in 18 parks and playgrounds; and Young Cultural Stewards a multimedia youth fellowship centering young people ages 12–14 with regional hubs across the North, West, and South sides of Chicago. ArtSeed: Mobile Creative Play ArtSeed engages over 2,000 youth (ages 3-12) across 18 parks through storytelling, music, movement, and nature play rooted in neighborhood stories. Children explore the histories and legacies of Chicago's community-based artists and imagine creative solutions to challenges in their own neighborhoods. Teaching artists engage practice of social emotional learning, foundations in social justice, and trauma-informed pedagogy to cultivate children and families invested in fostering the cultural practices and creative capital of their parks and communities.