A History of the Skullcap, Around the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Price List Premium · 2021

PRICE LIST PREMIUM · 2021 Pág. Link Ref. Nome Articolo PrecioPrezzo Prezzo GREEN IDEAS 6, 38 See photo 3209 HELDENS Altavoz Cargador/Charger speaker/Haut-parleur chageur € 45,940 7, 38 See photo 3208 STEVE Altavoz Inalámbrico/Wireless Speaker/Haut-parleur sans fil € 35,440 7, 56 See photo 3021 MARS Cargador Inalámbrico/Wireless charger/Chargeur sans fil € 32,185 8, 40 See photo 3206 KRAVIZ Altavoz Inalámbrico/Wireless Speaker/Haut-parleur sans fil € 17,065 8, 62 See photo 3023 NEPTUNE Puerto USB HUB/USB HUB/USB HUB € 12,025 9, 57 See photo 3022 GRAVITY Cargador Inalámbrico/Wireless charger/Chargeur sans fil € 25,150 9, 57 See photo 3024 CORE Organizador Cargador/Wireless charger/Chargeur sans € 26,040 10, 40 See photo 3207 HARDWELL Altavoz Inalámbrico/Wireless Speaker/Haut-parleur sans fil € 16,800 10, 39 See photo 3210 ALESSO Altavoz Inalámbrico/Wireless Speaker/Haut-parleur sans fil € 28,090 10, 58 See photo 3018 SOYUZ Cargador Inalámbrico/Wireless charger/Chargeur sans fil € 9,925 11, 46 See photo 3026 BLUES Auriculares Inalámbricos/Wireless earphones/Écouteurs sans fil € 41,740 11, 62 See photo 3019 ASTRO Cable Cargador/charging cable/charging cable € 6,300 11, 52 See photo 3355 ROSSUM Batería Externa/Power bank/Batterie externe € 33,075 12, 76 See photo 8034 STOA Bolígrafo/Ball pen/Stylo € 0,525 12, 76 See photo 8018 TUCUMA Bolígrafo Bambú/pen bamboo/bambou bambou € 0,735 12, 73 See photo 8031 SAGANO Bolígrafo ECO/Ball pen ECO/Stylo ECO € 1,815 13, 77 See photo 8036 KIOTO Set Escritura/Set de stylo/pen pencil set € 2,155 13, 76 See -

Bio Data DR. JAYADEVA YOGENDRA

4NCE Whenever we see Dr. Jayadeva, we are reminded of Patanjali's Yoga Sutra: "When one becomes disinterested even in Omniscience One attains perpetual discriminative enlightenment from which ensues the concentration known as Dharmamegha (Virtue Pouring Cloud)". - Yoga Sutra 4.29 He represents a mind free of negativity and totally virtuous. Whoever comes in contact with him will only be blessed. The Master, Dr Jayadeva, was teaching in the Yoga Teachers Training class at The Yoga Institute. After the simple but inspiring talk, as usual he said. IIAnyquestions?" After many questions about spirituality and Yoga, one young student asked, "Doctor Sahab how did you reach such a high state of development?" In his simple self-effacing way he did not say anything. Theyoung enthusiast persisted, 'Please tell us.II He just said, "Adisciplined mind." Here was the definition of Yoga of Patanjali, "roqa Chitta Vritti Nirodha" Restraining the modifications of the mind is Yoga. Naturally the next sutra also followed "Tada Drashtu Svarupe Avasthanam". "So that the spirit is established in its own true nature." Recently, there was a function to observe the 93fd Foundation Day of The Yoga Institute which was founded by Dr. Jayadeva's father, Shri Yogendraji - the Householder Yogi and known as "the Father of Modern Yoga Renaissance". At the end of very "learned" inspiring presentations, the compere requested Dr.Jayadeva." a man of few words" to speak. Dr.Jayadeva just said,"Practise Yoga.II Top: Mother Sita Devi Yogendra, Founder Shri Yogendraji, Dr. Jayadeva Yogendra, Hansaji Jayadeva Yogendra, Patanjali Jayadeva Yogendra. Bottom: Gauri Patanjali Yogendra, Soha Patanjali Yogendra, Dr. -

Capital No One Who Has Compared Without NATIONAL L..U.D Tv.Ry Frlday I Buy Her Som'tbeeng Nice for Wea Prejudice the Qualifications of Messrs

, LY 1 WOL. 257. LONG BRANCH, N. J., WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 1910. 8 PAGES PRICE ONE CENT ' (MANY ATTENDED FUNERAL JUDGE EMU£ WWE0 D. of L. service! Over the Body of Forme. Long Branch Resilient Laid Mm. W. D. Brand at West ' WAGON WRECKED, MAN POLICE AND MILITIA tc Heat With i. O. O. P. Cm Long branch.' msnlw at I slinniW Funeral services for Mrs, Warren Funeral servkus lor >p«MH Jud«* I). Brand were held Monday afternoon Moses I Engle, wbo died at' Lake- aC'-FIlp MY E. Church, West Lonj wood on Saturday, weir* beld yester- AND HORSE HURT AT WILL NOT INTERFERE day from bis borne In OcetJi anna* Branch. The services were largely at tended by relatives anfl friends. Rev. at that place. Tbe services C: B. KlwlKjr paid a touching tribute largely attended, many Long rn the deceased. The choir sang relatives 'iaB IrieniJi being . •What Are They Doing In Heaven SEA BRIGHT CROSSING WITH BIG STRIKE at the services A (reat mark , |T<)day?' "Looking This Way," and teem vaa thovn tbe deceaaad by tb« "fii That City'" The pall-beirerB were Beautiful flowers which were «»n(. .ilaj.ir M V. Poole, councilman C. A. Revs Dr» T&Uiua its Power Poolo, J. D. Van Mote, (ieorge A. MM Vehicle Smashed to Kindling Wood And Driver, Gaynor Orders Police Off Express Wagons in Newconducted tbe services, emdb referring lick. C. K. Clayton and I-ouls Mine. to the exemplary Ule lad by tie da- The floral tribute* were numerous add Joseph Strohmenger, An Oceanic Bottler, Es- York And Fort Rafuses to Use Troops in Jer- ceased Judge Engle was u teacher handsome, being contributed by the Tbe revised registry 1M for in tbe Bible claw of the East Lake following: W. -

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi's Experiments with the Indian

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi’s Experiments with the Indian Economy, c. 1915-1965 by Leslie Hempson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Co-Chair Professor Mrinalini Sinha, Co-Chair Associate Professor William Glover Associate Professor Matthew Hull Leslie Hempson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5195-1605 © Leslie Hempson 2018 DEDICATION To my parents, whose love and support has accompanied me every step of the way ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ACRONYMS v GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS vi ABSTRACT vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE AGRO-INDUSTRIAL DIVIDE 23 CHAPTER 2: ACCOUNTING FOR BUSINESS 53 CHAPTER 3: WRITING THE ECONOMY 89 CHAPTER 4: SPINNING EMPLOYMENT 130 CONCLUSION 179 APPENDIX: WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 183 BIBLIOGRAPHY 184 iii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 2.1 Advertisement for a list of businesses certified by AISA 59 3.1 A set of scales with coins used as weights 117 4.1 The ambar charkha in three-part form 146 4.2 Illustration from a KVIC album showing Mother India cradling the ambar 150 charkha 4.3 Illustration from a KVIC album showing giant hand cradling the ambar charkha 151 4.4 Illustration from a KVIC album showing the ambar charkha on a pedestal with 152 a modified version of the motto of the Indian republic on the front 4.5 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing the charkha to Mohenjo Daro 158 4.6 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing -

A Preliminary Study of the Inner Coffin and Mummy Cover Of

A PRELIMINARY STUDY OF THE INNER COFFIN AND MUMMY COVER OF NESYTANEBETTAWY FROM BAB EL-GUSUS (A.9) IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, WASHINGTON, D.C. by Alec J. Noah A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History The University of Memphis May 2013 Copyright © 2013 Alec Noah All rights reserved ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I must thank the National Museum of Natural History, particularly the assistant collection managers, David Hunt and David Rosenthal. I would also like to thank my advisor, Dr. Nigel Strudwick, for his guidance, suggestions, and willingness to help at every step of this project, and my thesis committee, Dr. Lorelei H. Corcoran and Dr. Patricia V. Podzorski, for their detailed comments which improved the final draft of this thesis. I would like to thank Grace Lahneman for introducing me to the coffin of Nesytanebettawy and for her support throughout this entire process. I am also grateful for the Lahneman family for graciously hosting me in Maryland on multiple occasions while I examined the coffin. Most importantly, I would like to thank my parents. Without their support, none of this would have been possible. iv ABSTRACT Noah, Alec. M.A. The University of Memphis. May 2013. A Preliminary Study of the Inner Coffin and Mummy Cover of Nesytanebettawy from Bab el-Gusus (A.9) in the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Major Professor: Nigel Strudwick, Ph.D. The coffin of Nesytanebettawy (A.9) was retrieved from the second Deir el Bahari cache in the Bab el-Gusus tomb and was presented to the National Museum of Natural History in 1893. -

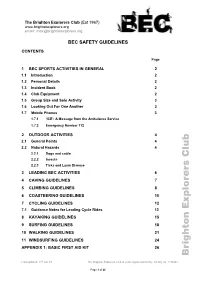

B Rig H to N E X P Lo Re Rs C Lu B

The Brighton Explorers Club (Est 1967) www.brightonexplorers.org email: [email protected] BEC SAFETY GUIDELINES CONTENTS Page 1 BEC SPORTS ACTIVITIES IN GENERAL 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Personal Details 2 1.3 Incident Book 2 1.4 Club Equipment 2 1.5 Group Size and Solo Activity 3 1.6 Looking Out For One Another 3 1.7 Mobile Phones 3 1.7.1 ‘ICE’: A Message from the Ambulance Service 1.7.2 Emergency Number 112 2 OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES 4 2.1 General Points 4 2.2 Natural Hazards 4 2.2.1 Dogs and cattle 2.2.2 Insects 2.2.3 Ticks and Lyme Disease 3 LEADING BEC ACTIVITIES 6 4 CAVING GUIDELINES 7 5 CLIMBING GUIDELINES 8 6 COASTEERING GUIDELINES 10 7 CYCLING GUIDELINES 12 7.1 Guidance Notes for Leading Cycle Rides 13 8 KAYAKING GUIDELINES 15 9 SURFING GUIDELINES 18 10 WALKING GUIDELINES 21 11 WINDSURFING GUIDELINES 24 APPENDIX 1: BASIC FIRST AID KIT 26 Brighton Explorers Club Last updated: 11th Jan 15 The Brighton Explorers Club is a UK registered charity. Charity no. 1156361 Page 1 of 26 BEC SAFETY GUIDELINES 1. BEC SPORTS ACTIVITIES IN GENERAL 1.1 Introduction Brighton Explorers Club (BEC) exists to encourage members to enjoy a variety of sporting pursuits; BEC is a club and not an activity centre, where the activities promoted by BEC can be dangerous if undertaken without consideration for the appropriate safety requirements. BEC is committed to maintaining high standards of safety. This document defines reasonable precautions to ensure that activities are carried out under safe conditions; to encourage all members to participate in club activities in a safe manner. -

If the Hat Fits, Wear It!

If the hat fits, wear it! By Canon Jim Foley Before I put pen to paper let me declare my interests. My grandfather, Michael Foley, was a silk hatter in one of the many small artisan businesses in Claythorn Street that were so characteristic of the Calton district of Glasgow in late Victorian times. Hence my genetic interest in hats of any kind, from top hats that kept you at a safe distance, to fascinators that would knock your eye out if you got too close. There are hats and hats. Beaver: more of a hat than an animal As students for the priesthood in Rome the wearing of a ‘beaver’ was an obligatory part of clerical dress. Later, as young priests we were required, by decree of the Glasgow Synod, to wear a hat when out and about our parishes. But then, so did most respectable citizens. A hat could alert you to the social standing of a citizen at a distance of a hundred yards. The earliest ‘top’ hats, known colloquially as ‘lum’ hats, signalled the approach of a doctor, a priest or an undertaker, often in that order. With the invention of the combustion engine and the tram, lum hats had to be shortened, unless the wearer could be persuaded to sit in the upper deck exposed to the elements with the risk of losing the hat all together. I understand that the process of shortening these hats by a few inches led to a brief revival of the style and of the Foley family fortunes, but not for long. -

1ST HINCHLEY WOOD SCOUT TROOP - EQUIPMENT LIST You Will Need to Provide Personal Equipment for Camping, Outdoor Activities Etc

1ST HINCHLEY WOOD SCOUT TROOP - EQUIPMENT LIST You will need to provide personal equipment for camping, outdoor activities etc. as listed below. We are happy to advise on equipment selection and suppliers etc. Most offer discounts to Scouts, do not be afraid to ask! Loss of or damage to personal property of Group members (only) when on Scout activities is covered by an insurance policy held by the Group. Cover is to a maximum of £400 per individual (£200 max each item, excess £15) and is subject to exclusions (details on request). We sometimes do have some second hand items (eg hike boots) for loan, please ask! Please mark everything possible (especially uniform) with your name in a visible place! NORMAL CAMP KIT ------------------------------- CANOEING/KAYAKING KIT---------------------- Rucsac, Kit Bag or holdall to contain your kit (please do not bring your kit in bin liners!) T-Shirt Sweatshirt Day Sac (useful for travelling & activities off Swimming Shorts site). Bring one with two shoulder straps. Waterproof Top (Cagoule) Normal Scout Uniform Waterproof Overtrousers (for canoeing) Wire Coat Hanger (to hang uniform in tent) Canvas Shoes/old Trainers/wet suit shoes Plenty of warm clothes: Towel & change of clothes inc shoes Underclothes, Handkerchiefs Carrier bag for wet kit T-Shirts, Sweatshirts/Jumpers, Fleece HIKING KIT -------------------------------------------- Shorts, Trousers, Jeans Shoes &/or Trainers Day Sac – a comfortable one big enough for what you have to carry but not huge! Bring one with two shoulder Sleeping mat (optional -

Glengarry Highland Games in Maxville, July 30

-~--- ------------------------- I .,- ·---·-··· --···-··--~, I ' I I The Glengarry News i i extends aliurufrecf tliousand ivdcomes I \ -------- - ------··---~' • • • --.,-,,_..•,-,: -.!3',1.:,,_;..._";a,.~·~,.,~:¥,-. r- - -:+-·_ TO YOUR GOOD HEALTH · ·: . ' ~ .- - . ... ~ - . - - - " - ~Wzhrl11,hlr2!,IW lria,07Et. Great leaders opened games by Anaaa H. McDonell The Rt. Hon. Edward chose their own home town Robt. H. Saunders, CBF, desk, ably assisted by his MacRae; 1961-62, Dr. Don Successful continuity of Schreyer, governor general lassie, Cathy MacEwan. A Q.C., chairman of Ontario wife Leila. And Angus H. Gamble; 1963-64, Wm. R. any community enterprise, of Canada and his wife, Her decade later, 1976, Mrs. Hydro was the 1950 guest. McDonell, 1964. MacEwen; 1965-66, Leslie such as the Glengarry Excellency Lily Schreyer. Alice MacNabb of .Mac And turning to the judic Presidents during the 36 Clark; 1967-68, Hugh Highland Games, for al Following the 1948 found Nabb of Clan MacLeod, iary, Chief Justice Kenneth years: Smith; 1969-70, R. W. most two score years is an ing of the Games, premiers Scotland, represented Charles MacKay, Mont MacLennan; 1971-72, Wal played a similar role in Dame Flora MacLeod. real, 1974. 1948, Peter Macinnes; achievement equaled by ter Blaney; 1973-74, Garry officiating. Two years later, The Games having a Representing the Clans 1949, A. S. MacIntosh; only a few counterparts. Smith; 1975-76-77, D. E. Continuity of having pre 1950, Hon. Leslie Frost, basic. sports background, in addition to the MacLeods 1950, C. L. MacGregor; 1951, Ken Barton; 1952, D. stigious Canadian person premier of Ontario was in the executive obviously were: Dave Grundie, Grand MacMaster; 1978-79, Ian D. -

The Fiction of Gothic Egypt and British Imperial Paranoia: the Curse of the Suez Canal

The Fiction of Gothic Egypt and British Imperial Paranoia: The Curse of the Suez Canal AILISE BULFIN Trinity College, Dublin “Ah, my nineteenth-century friend, your father stole me from the land of my birth, and from the resting place the gods decreed for me; but beware, for retribution is pursuing you, and is even now close upon your heels.” —Guy Boothby, Pharos the Egyptian, 1899 What of this piercing of the sands? What of this union of the seas?… What good or ill from LESSEPS’ cut Eastward and Westward shall proceed? —“Latest—From the Sphinx,” Punch, 57 (27 November 1869), 210 IN 1859 FERDINAND DE LESSEPS began his great endeavour to sunder the isthmus of Suez and connect the Mediterranean with the Red Sea, the Occident with the Orient, simultaneously altering the ge- ography of the earth and irrevocably upsetting the precarious global balance of power. Ten years later the eyes of the world were upon Egypt as the Suez Canal was inaugurated amidst extravagant Franco-Egyp- tian celebrations in which a glittering cast of international dignitar- ies participated. That the opening of the canal would be momentous was acknowledged at the time, though the nature of its impact was a matter for speculation, as the question posed above by Punch implies. While its codevelopers France and Egypt pinned great hopes on the ca- nal, Britain was understandably suspicious of an endeavor that could potentially undermine its global imperial dominance—it would bring India nearer, but also make it more vulnerable to rival powers. The inauguration celebrations -

HP Sponsor Brochure

Please indicate your Fancy Hat Party Sponsorship U The Top Hat $25,000 U The Derby $10,000 U The Fedora $ 5,000 U The Boater $ 2,500 U The Pillbox $ 1,500 U The Beanie $ 500 4 Lime/icon and Fa~/eion S/ion’ /0 Sponsorship name as you would like it to appear in The HoJ/ie/at HoJ/ii/añT~’ Hour the program: Contact Name: Telephone: HOSPIIAL HOSP11AL~~Y HOUSE Email: Treating guests like family since 1984 Address: 612 East Marshall Street Richmond, VA 23219 804-828-6901 a- ~ State: Zip: 804-828-6913 Fax www.hhhrichmond.org U Please invoice me Trea&’g ákc’ jam4j Juice 1914 U Credit Card Information gutom U Visa U Master Card U AMEX Amount to be charged: $ Foam/in, JD~6ó1c Phefpd’ Name on card: Mother of Olympic Gold Medalist, Credit Card N Michael Phelps Exp. Date: Signature: Friday, May 10, 2013 Checks should be made payable to: 11:30 to 1:30 pm The Hospital Hospitality House Please return to: The Science Museum of Virginia The Hospital Hospitality House 612 East Marshall Street Thaihimer Pavilion Richmond, VA 23219 Or go to www.hhhrichmond.org Currently in its 16th year, The Fancy SPONSORSHIP The Fedora $5,000 Hat Party Luncheon has become one • Seating for 10 guests at the Fancy Hat Party or of the Hospital Hospitality House’s OPPORTUNITIES Hats Off! party signature fundraising events with Preferred table service at Hats Off! party, if selected over 500 attendees each year. The Top Hat - $25,000 Recognition in promotional materials, public Title Sponsorship recognition at both the Whether you have been a sponsor in relations and advertising Fancy Hat Party and Hats Off! parties years past, or are new to the Fancy Corporate logo on large screen monitors Preferred seating for 20 guests at both parties Hat Party this year, please accept our during sponsored party Preferred table service at the Hats Off! party Corporate logo on t-shirt at Hats Off! party, if sincere thanks for your support. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Headscarf in France, Turkey, and the United States Hera Hashmi

University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class Volume 10 | Issue 2 Article 8 Too Much to Bare? A Comparative Analysis of the Headscarf in France, Turkey, and the United States Hera Hashmi Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/rrgc Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hera Hashmi, Too Much to Bare? A Comparative Analysis of the Headscarf in France, Turkey, and the United States, 10 U. Md. L.J. Race Relig. Gender & Class 409 (2010). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/rrgc/vol10/iss2/8 This Notes & Comments is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOO MUCH TO BARE? A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE HEADSCARF IN FRANCE, TURKEY, AND THE UNITED STATES BY HERA HASHMI* INTRODUCTION In July 2009, a man stabbed and killed a pregnant woman wearing a headscarf in a German courtroom during an appellate trial for his Islamophobic remarks against her.1 Her death led to outrage around the world, and she became known as the "martyr of the veil," a woman killed for her religious belief.2 Yet it was just a simple piece of cloth that evoked this violent reaction. Such Islamaphobic sentiments seem to be spreading throughout various parts of the world. In 2004, France banned headscarves and all conspicuous religious symbols from public classrooms.3 In 2005, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR)4 upheld Turkey's headscarf ban barring thousands of headscarf-wearing women from attending schools, universities, and entering government buildings in a country where a majority of the population is Muslim.