Volume 3, Issue 6 November—December 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women

University of San Diego Digital USD Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Department of Theology and Religious Studies 2019 Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Karma Lekshe Tsomo PhD University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Digital USD Citation Tsomo, Karma Lekshe PhD, "Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women" (2019). Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship. 25. https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Section Titles Placed Here | I Out of the Shadows Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU First Edition: Sri Satguru Publications 2006 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2019 Copyright © 2019 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover design Copyright © 2006 Allen Wynar Sakyadhita Conference Poster -

A Buddhist Inspiration for a Contemporary Psychotherapy

1 A BUDDHIST INSPIRATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY PSYCHOTHERAPY Gay Watson Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London. 1996 ProQuest Number: 10731695 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731695 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT It is almost exactly one hundred years since the popular and not merely academic dissemination of Buddhism in the West began. During this time a dialogue has grown up between Buddhism and the Western discipline of psychotherapy. It is the contention of this work that Buddhist philosophy and praxis have much to offer a contemporary psychotherapy. Firstly, in general, for its long history of the experiential exploration of mind and for the practices of cultivation based thereon, and secondly, more specifically, for the relevance and resonance of specific Buddhist doctrines to contemporary problematics. Thus, this work attempts, on the basis of a three-way conversation between Buddhism, psychotherapy and various themes from contemporary discourse, to suggest a psychotherapy that may be helpful and relevant to the current horizons of thought and contemporary psychopathologies which are substantially different from those prevalent at the time of psychotherapy's early years. -

Soka Gakkai in Italy: Success and Controversies

$ The Journal of CESNUR $ Soka Gakkai in Italy: Success and Controversies Massimo Introvigne CESNUR (Center for Studies on New Religions) [email protected] ABSTRACT: Italy is the Western country with the highest percentage of Soka Gakkai members. This success needs to be explained. In its first part, the article discusses the history of Soka Gakkai in Italy, from the arrival of the first Japanese pioneers to the phenomenal expansion in the 21st century. It also mentions some internal problems, the relationship with the Italian authorities, and the opposition by disgruntled ex-members. In the second part, possible reasons for the success are examined through a comparison with another Japanese movement that managed to establish a presence in Italy (although a smaller one), Sûkyô Mahikari. Unlike Sûkyô Mahikari, Soka Gakkai proposed a humanistic form of religion presented as fully compatible with modern science, and succeeded in “de-Japanizing” its spiritual message, persuading Italian devotees that it was not “Japanese” but universal. KEYWORDS: Soka Gakkai, Soka Gakkai in Italy, Buddhism in Italy, Japanese religious movements, Japanese religious movements in Italy. Introduction Soka Gakkai is the fastest-growing Buddhist movement in the world. The history and reasons of this growth have been investigated in Japan (McLaughlin 2019), as well as in the United Kingdom (Wilson and Dobbelaere 1994; Dobbelaere 1995), Quebec (Metraux 1997), and the United States (Dator 1969; Hurst 1992; Snow 1993; Hammond and Machacek 1999; for early studies of Soka Gakkai, see also White 1970; Metraux 1988; Machacek and Wilson 2000; Seager 2006). Few, however, have discussed how important has been the growth of Soka Gakkai in Italy, a country where religious minorities are all comparatively small. -

The Principles of Tibetan Medicine a Medical System Based on Compassion

THE MIRROR The International Newspaper of the Dzog-chen Community Volume 1 Issue 11, September 1991 NAMKHA The principles of Tibetan medicine A medical system based on compassion Germany An introduction to Dzog-chen Namkha is a Tibetan word, which page 5 means space. This word is also used as the name of an object made of France sticks and coloured threads. InTibet, Three day Paris conference Namkhas have been used a great deal yet few people understand page 6 exactly how they work. Denmark In 1983, Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche clarified the ways that Namkhas can Yantra yoga group actually be used by a person to page 5 harmonise his or her energies. This involves a certain understanding of U.S.A. Tibetan astrology related to the New York individual. Once the astrological Kalacakra Initiation signs and aspects of an individual are understood, a Namkha can be The Medicine Buddha page 4 constructed and with the use of Tsegyalgar appropriate rituals, it can become a In the Mahay a na tradition, when we practise or study, from the start we look Lobpon Tenzin Namdak practical aid in making one's life at our motivation. If we do not have good motivation then we cultivate it in teaches in October more harmonious. order to benefit others. There is an explanation of the qualities that a doctor needs to have. If people do not have these qualities, then they need to cultivate page 5 page 14 them. page 9 Australia New Mexico Some views on death Remembering Dr. Lopsang Dolma page 13 A group of people in Santa Fe now The story of one of Tibet's famous women doctors New Zealand gather together regularly for group Teachings transmitted by practice and activities as the Dzog- Bom in the Kyirong district of West years in exile, she finally resumed bringing the unique system of radio in Auckland chen Community of New Mexico. -

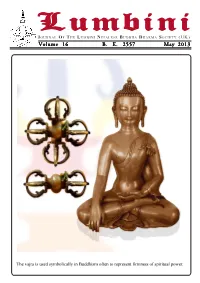

Lumbini Journal 13.Pmd

LumbiniLumbiniLumbini J OURNAL O F T HE L UMBINI N EPALESE B UDDHA D HARMA S OCIETY (UK) Volume 16 B. E. 2557 May 2013 The vajra is used symbolically in Buddhism often to represent firmness of spiritual power. Lumbini Nepalese Buddha Dharma Society (UK) uddha was born more than 2600 years ago at Lumbini in Nepal. His teachings of existence of suffering and Lumbini the way out of the suffering are applicable today as they were B Journal of The Lumbini Nepalese Buddha Dharma Society (UK) applicable then. The middle way he preached is more appropriate now than ever before. Lumbini is the journal of LNBDS (UK) and published annually For centuries Buddhism remained the religion of the East. Recently, depending upon funds and written material; and distributed free more and more Westerners are learning about it and practising Dharma of charge as Dharma Dana. It is our hope that the journal will serve for the spiritual and physical well-being and happiness. As a result of as a medium for: this interest many monasteries and Buddhist organisations have been established in the West, including in the UK. Most have Asian 1.Communication between the society, the members and other connections but others are unique to the West e.g. Friends of Western interested groups. Buddhist Order. 2.Publication of news and activities about Buddhism in the United Nepalese, residing in the UK, wishing to practice the Dharma for their Kingdom, Nepal and other countries. spiritual development, turned to them as there were no such Nepalese organisations. Therefore, a group of Nepalese met in February 1997 3.Explaining various aspects of Dharma in simple and easily and founded Lumbini Nepalese Buddha Dharma Society (UK) to fill understood language for all age groups. -

Buddhism After the Lord Buddha's Attainment

www.kalyanamitra.org THE HISTORY OF BUDDHISM GB 405E Translated by Dr. Anunya Methmanus May 2555 B.E. www.kalyanamitra.org Kindly send your feedback or advice to: DOU Liaison Office P.O. Box 69 Khlong Luang Pathum Thani 12120 THAILAND Tel. : (66 2) 901-1013, (66 2) 831-1000 #2261 Fax : (66 2) 901-1014 Email : [email protected] www.kalyanamitra.org CONTENTS Foreword i Course Syllabus ii Method of Study iii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 What Is the Definition of History? 3 1.2 Why Must We Learn about History? 5 1.3 How to Learn about History 8 Chapter 2 Ancient Indian Society 11 2.1 The Geography and History of Ancient India 13 2.2 The Origin and Development of Brahmanism 17 Chapter 3 India during the Lord Buddha’s Time 31 3.1 Economy and Government 34 3.2 Masters of the Six Schools of Thought 37 3.3 The Lord Buddha’s History 42 3.4 The Happening of Buddhism and the Change in India’s Religious Beliefs 44 and Cultures Chapter 4 Buddhism after the Lord Buddha’s Attainment of Complete Nibbana 51 4.1 Buddhism, Five Hundred Years after the Lord Buddha’s Attainment of 54 Complete Nibbana 4.2 Buddhism between 500 and 1000 B.E. 61 4.3 The Decline of Buddhism in India 75 www.kalyanamitra.org Chapter 5 Buddhism in Asia 85 5.1 An Overview of Buddhism in Asia 87 5.2 The History of Buddhism in Asia 89 Chapter 6 Buddhism in the West 147 6.1 An Overview of Buddhism in the West 149 6.2 The History of Buddhism in the West 154 6.3 The Reason Some Westerners Convert to Buddhism 180 Chapter 7 Conclusion 183 7.1 Summary of the History of Buddhism 185 7.2 Summary of Important Events in the History of Buddhism 186 www.kalyanamitra.org FOREWORD The course “The History of Buddhism GB 405E” provides information about ancient India in terms of the different religious beliefs subscribed by the people of ancient India before the happening of Buddhism. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/25/2021 02:47:34PM Via Free Access MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities Regular 19.2, 2016

BUDDHISM IN ITALY IN เอกสารที่อางอิงบางชิ้นในบทความนี้ไมเคยตีพิมพ THE NINETEENTH มากอน หรือเปนเอกสารหายากจากหอจดหมายเหตุ 1 CENTURY ในประเทศอิตาลี Paolo Euron2 Abstract บทคัดยอ First reports on Buddhism arrived in Italy in the sixteenth century through Italian Catholic missionaries. Later several รายงานเกี่ยวกับพุทธศาสนามาถึงประเทศอิตาลีเปน scholars developed a philological and ครั้งแรกในราวคริสตวรรษที่สิบหก ผานทางคณะ philosophical understanding of it. The attitude toward Buddhism changed from มิชชันนารีของอิตาลี ในเวลาตอมานักวิชาการได an anthropological interest to a พัฒนาความเขาใจดานภาษาและปรัชญาเกี่ยวกับ philological study. In the academic field of philology the Theravāda tradition and the พุทธศาสนา ทาทีตอพุทธศาสนาไดเปลี่ยนจากความ Siamese edition of Tripitaka had great สนใจดานมานุษยวิทยา มาเปนการศึกษาดานภาษา importance. The spread of Buddhism in Italy in the nineteenth century also ในการศึกษาดานนิรุกติศาสตร ประเพณีของเถรวาท increasingly influenced Italian culture and และพระไตรปฎกฉบับของสยามมีความสําคัญมาก ideas. Outside of academic debate Buddhism became a subject of apologetics การแพรกระจายของพุทธศาสนาในอิตาลีใน and philosophy as well as a topic of คริสตศตวรรษที่สิบเกา ก็ไดรับอิทธิจากวัฒนธรรม general interest. This essay is based on books and printed material published in และแนวคิดตางๆของอิตาลีดวย ในบรรดาผูที่อยู Italy before the twentieth century. It นอกวงการวิชาการ พุทธศาสนาไดกลายเปนหัวขอ contains the complete bibliography of Italian studies on Buddhism in the ของการพยายามแกตาง และของวิชาปรัชญา รวม nineteenth century. Some texts -

SEPTEMBER, 1910 Coronation Oath Buddhism in Italy China Anti

CARIBBEAN WATCHMAN • ej...k , SEPTEMBER, 1910 Coronation Oath Buddhism in Italy China Anti-Manchu Is World Peace at Hand? Millennium or Armageddon? Is the World Growing Better? Flying Machines vs. Dreadnaughts Home Treatments The Resurrection The Lord's Day PRICE, FIVE CENTS GOI.1) Watchman Publishing Assn., Cristobal, C. Z., Panama o.&,madadat&atwatmat&adadaecm.adatm atfto .* Jesus Is Coming Again. C. P. WHITFORD. F. S. STANTON, M1.15. Bac. 1. Je - sus the Saviour is corn - ing, This is the message pf love; 2. He who was born in a man - ger, And up - on Cal- va - ry slain, 3. Signs ev'rywhere are ft 1-fill - ing, Hearts of men failing for fear; 4. Help us,dear Saviour,to love Thee, Help us to feed on Thy word; -o-. ffffff, • r -KM :num egoonammiumm V • • Who would not welcome the Saviour, Coming from bright worlds a-bove? Soon will be seen in the heav - ens, Corn- ing to earth once a gain. Troub-les on earth are in-creas - ing, Showing Christ's advent is neat. Comfort our hearts while we're waiting,Waiting for Thee, blessed Lord. -do- r r CHORUS. 0' • • • V Je - sus is corn - ing, Je-sus is corning a - gain; .... Je-sus is coming,is coming a-gain, a - gain; -0- • t t e • • 0 I V V V—V V V 11--• I —1:1 Sound it a-broad o'er the na - tions, Je-sus the Saviour will reign. • - AI- -IF • All rights reserved to Charles P, Whitford, THE Caribbean Watchman Vol. -

Mental Health Among Italian Nichiren Buddhists: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Exploratory Study

religions Brief Report Mental Health among Italian Nichiren Buddhists: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Exploratory Study Nicola Luigi Bragazzi * , Lorenzo Ballico and Giovanni Del Puente Department of Neuroscience, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Genetics, Maternal and Child Health (DINOGMI), Section of Psychiatry, Genoa University, 16132 Genoa, Italy; [email protected] (L.B.); [email protected] (G.D.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 14 February 2019; Accepted: 9 May 2019; Published: 10 May 2019 Abstract: Religiosity/spirituality is generally considered as a powerful tool for adjusting and coping with stressors, attributing purposes and meanings (either existential/philosophical, cognitive, or behavioral ones) to daily situations and contexts. While studies generally investigate these effects in Judaism and Christianity believers, there is a dearth of data concerning oriental religions. We sampled from Italian Nichiren Buddhists, the most widespread branch of Buddhism in Italy (n = 391). Participants were Buddhists on average since 5 years and self-defined moderate practitioners. Adaptive strategies exhibited higher scores than maladaptive ones. Specifically, the adaptive strategy of active coping positively correlated with self-evaluated degree of being a practicing Buddhist, as well as positive reframing and religion, while maladaptive strategies such as use of substances, venting and behavioral disengagement correlated negatively. Only the subscale of religion correlated significantly and positively with the time from which the participant had become Buddhist, while the use of emotional support correlated negatively. Most participants had a predominantly internal locus of control. External locus of control negatively correlated with time the participant became Buddhist and the self-reported degree of being a practicing Buddhist, whereas internal locus positively correlated only with the latter variable. -

Budespengbj.Pdf

Contents Acknowledgements Foreword Eassay 1 The Emergence of Buddhism and the 01 2600 th Anniversary of the Buddhaís Enlightenment Oliver Abenayaka Eassay 2 Global Spread of Buddhism Through the Ages 15 Olcott Gunasekera Eassay 3 Buddhism in India 47 Mahesh A Deokar Eassay 4 Buddhism in Sri Lanka 85 Rev. Nabirittankadavara Gnanaratana Thera Asanga Tilakaratne Sanath Nanayakkara Eassay 5 Buddhism in Nepal 105 Min Bahadur Shakya Eassay 6 Buddhism in Bangladesh 115 Bhikkhu Saranapala Eassay 7 Buddhism in Bhutan 125 Manjiri Bhalerao Eassay 8 Buddhism in Tibet 137 Geshe Ngawang Samten Eassay 9 Buddhism in the Union of Myanmar 147 Ven. Khammai Dhammasami Eassay 10 Buddhism in Thailand 173 Ven. Anil Sakya Quentin (Trais) Pearson III Eassay 11 Buddhism in Laos 187 Justin McDaniel Eassay 12 Buddhism in Cambodia 201 Ian Harris Eassay 13 Buddhism in Vietnam. 213 Ven. Dr. Thick Tam Duc Eassay 14 Buddhism in Malaysia 219 P. L. Wong Eassay 15 Buddhism in Singapore 237 Hue Guan Thye Eassay 16 Buddhism in Indonesia 251 Rev. Sasminto (Dhammasiri) Eassay 17 Buddhism in China 263 Lawrence YK Lau Eassay 18 Buddhism in Taiwan 277 Kai - Wen Lu Eassay 19 Buddhism in Hong Kong 285 John Shannon Eassay 20 Buddhism in Korea 293 Ko Young - Seop, Sungtaek Cho Eassay 21 Buddhism in Japan 317 Toshi ichi Endo Eassay 22 Buddhism in Central Asia 329 Bindu Urugodawatte Eassay 23 Buddhism in Russia 359 S. Y. Lepekhov Eassay 24 Buddhism in Mongolia 373 S. Y. Lepekhov Eassay 25 Buddhism in Central and Eastern Europe 381 Tomasë Havlicek, Helena Janu Eassay 26 Buddhism in the United Kingdom. -

BSR Contents Including Reviews- Vols. 1-22 1983-2005

1 Buddhist Studies Review Tables of Contents, including book reviews, 1983-2008 ISSN 0265-2897 Editor: Russell Webb 2004 (with Rupert Gethin as joint editor for 2001 issues) Assistant Editor: Bhikkhu Pāsādika, plus, from 1987, Sara Boin-Webb Original Advisory Committee: Ven. Thích Huyên-Vi (Spiritual Advisor), André Bareau, Eric Cheetam, Lance Cousins, Hubert Durt, Eddy Moerloose, Peter Skilling and Paul Williams. Charles Prebish added in 1994. BSR adopted by the UK Association for Buddhist Studies in 1998 Cathy Cantwell and Rupert Gethin added to Edirorial Board as UKABS links in 1999. Editor for 2005 edition: Rupert Gthin Mahinda Deegalle (Book Reviews Editor) Editorial Board: T.H. Barrett, Cathy Cantwell, Elizabeth Harris, Peter Harvey, Ulrich Pagel, Charles S. Prebish, Andrew Skilton From 2006 (Vol.23) Buddhist Studies Review was published by Equinox Publishing, Ltd.: General Editor: Peter Harvey (Sunderland) Book Reviews Editor: Mahinda Deegalle (Bath Spa) -> 2009; Alice Collett (York St John) and Sarah Shaw (Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies) 2010 -> Editorial Board T.H. Barrett (School of Oriental and African Studies, SOAS), Ven. Khammai Dhammasami (Oxford Buddhist Vihara), Lucia Dolce (SOAS), Rupert Gethin (Bristol University), Elizabeth Harris (Methodist Church House: Inter-faith Relation), Rob Mayer (Oriental Institute, Oxford University), Ulrich Pagel (SOAS), Ashley Thompson (Leeds University), Will Tuldhar-Douglas (Aberdeen University), Andrew Skilling (formally Cardiff University). Editorial Advisory Board Mark Allon (Sydney University), Robert Buswell (UCLA), Lance Cousins (Oxford; formerly Manchester University), Richard Gombrich (Oxford University), Paul Harrison (Independent Scholar), Ann Heirman (Ghent University), K.R. Norman (Cambridge University), Charles S. Prebish (Pennsylvania State University), Cristina Scherrer- Schaub (Lausanne University), Paul Williams (Bristol University). -

Una Rivoluzione Spirituale

A Spiritual Una rivoluzione Revolution spirituale The History of the Lama Tzong Khapa Institute of Pomaia La storia dell’Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa di Pomaia testi di / texts by Massimo Corona Contents / Sommario 4 Introduction 5 Introduzione 14 Preface 15 Prefazione 16 The Origins 17 Le origini 58 The Castle of Pomaia 59 Il castello di Pomaia 110 The First Masters 111 I primi Maestri Introduction Introduzione In regards to the Lama Tzong Khapa Institute, I remember that a Swiss couple, Chris and Barbara In merito alla storia dell’Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa, mi pare di ricordare che Chris e Barbara Vautier organized a course in Switzerland (in 1975), I think after they came to Kopan (they Vautier organizzarono un corso in Svizzera e uno dei primi monaci occidentali, Alan Wallace, attended the third Kopan course, 1973). This is how it usually happens, they come to Kopan che stava studiando con Ghesce Rabten, vi prese parte. Penso che Chris e Barbara abbiano and then they organize a course in the West, they got inspired and made their lives meaningful. partecipato prima a un corso di Kopan (il terzo) e ne siano stati ispirati. Questo è quello che I don’t remember the name of the place. At that time Alan Wallace was there, he was one of the first succede di solito, gli occidentali vengono a Kopan e poi aprono un centro nel loro paese: così Westerners to be ordained, and he was studying with Ghesce Rabten. I remember that I was simply la loro vita acquista significato. reading from “The Wish-fulfilling Golden Sun” (the notes from Kopan third meditations course), Chris e Barbara ci invitarono in Svizzera, non ricordo il nome del posto.